Selecting a Topic: What Makes a Good Research Question?

Think now about the first step of the scientific method: identify a problem. You could also phrase this as “find a good question.” Basically, curiosity drives science, and good questions are the heart of research design. Identifying a strong research question is the hardest part of research for some people, but some find it the most enjoyable task and one of the easier steps of research. Having an open mind and the curiosity to let questions lead you can be helpful here.

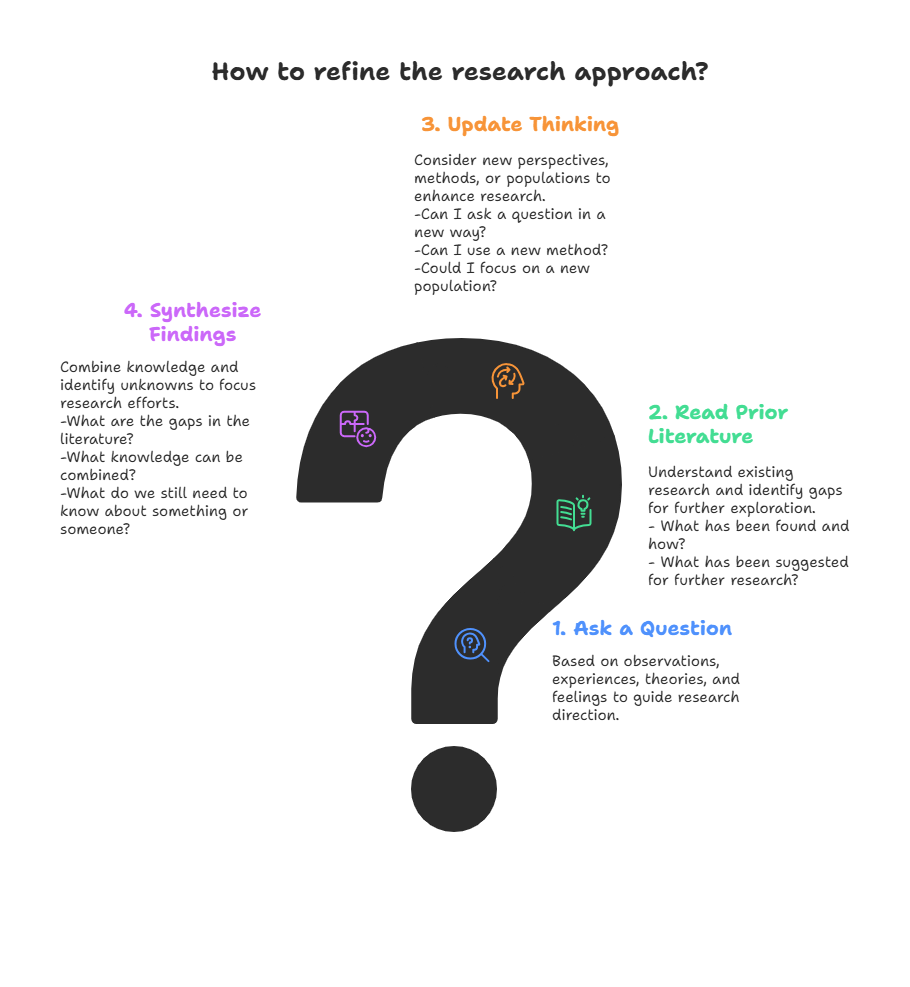

Note that research is cyclical, and even within the steps of the method you can sometimes loop back on yourself in an iterative process. That’s not a bad thing; it just means that you can learn, grow, and adjust as you go along for many parts of the process (though not all—the systematic part of research demands that parts of the process stick closely to a preset plan—that comes much later than first asking the question.)

* This image was created using Napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight.

Let’s work on helping you discover a question that interests you to get started. Putting some effort into finding something that really excites you now will make the process of research design more fun for yourself. If you already have something in mind, excellent! We can simply work on clarifying that question in the next few steps. If you don’t have something in mind yet, that’s completely fine. We’ll work to get your creative juices flowing before we get into the nitty-gritty.

Possible Topics

On that note, let’s talk topics, subjects, areas, or whatever you want to call it. Family science, like the rest of the behavioral and social sciences, is huge and covers a large variety of topics. Because of this, readers of this text will have an enormous variety of interests! Think about what topics you might have read about in a prior class, subjects you discuss with your family and friends, or ideas that you could spend hours thinking or reading about. Set a timer for 1 minute and write down as many possible topics of interest as you can think of.

If you’re struggling to come up with ideas, or if you just want to further expand your possibilities, consider trying some of the following methods:

- Think about “what” and “why” questions you’ve had before and expand on those. For example, what are the best methods of treating marital problems? Or why are people receiving SNAP more likely to be obese?

- If you already have practice experience in an area through employment, an internship, or volunteer work, think about practice issues you noticed in the placement.

- Ask a professor, preferably one active in research, about possible topics.

- Read departmental information on research interests of the faculty. Faculty research interests vary widely, and it might surprise you what they have published on in the past. Most departmental websites post the curriculum vitae, or CV, of faculty which lists their publications, credentials, and interests.

- Read a research paper that interests you. The paper’s literature review or background section will provide insight into the research question the author was seeking to address with their study. Is the research incomplete, imprecise, biased, or inconsistent? As you’re reading the paper, look for what’s missing. These may be “gaps in the literature” that you might explore in your own study. The conclusion or discussion section at the end may also offer some questions for future exploration. A recent blog posting in Science (Pain, 2016) provides several tips from researchers and graduate students on how to effectively read these papers.

- Think about papers you enjoyed researching and writing in other classes. Research is a unique class and will use the tools of social science for you to think more in depth about a topic. It will bring a new perspective that will deepen your knowledge of the topic.

- Identify and browse journals related to your research interests. Faculty and librarians can help you identify relevant journals in your field and specific areas of interest.

Now that your creativity is starting to flow and you’ve got a few possible topics in mind, let’s talk about what makes a topic useful for defining a research question. Some topics are a little easier to work with than others, maybe because there’s more to work from in terms of prior literature, maybe because something is personal to you (this can also work against you, though!), or maybe because it’s something that could have immediate and obvious impact on people’s lives. All of these are valid reasons for being interested in a topic and wanting to refine it towards a research question.

Using AI to Refine Your Topic

Show

You Lead, AI Follows: Using AI to Refine Your Research Topic

One way students may utilize AI in this class is as a tool to generate ideas and/or offer a new perspective concerning their topic of interest. It can serve as a starting point as you begin to explore your area of interest. For instance, it is my experience that students often start with a broad topic of interest. AI can be a valuable tool for refining these broad ideas. AI can help you become more focused and refine your specific areas of interest. However, it is important to emphasize that we expect and encourage you to take the lead in this process. You should be the guiding force in this endeavor. By the questions you ask, you will be guiding the AI rather than allowing AI to guide you. Let me clarify what I mean by this.

When you take the lead, you actively define the focus and scope of your exploration. For example, you might begin with a broad topic like family dynamics. By asking AI-targeted questions about specific aspects of family dynamics that interest you—such as the impact of communication styles or successful types of family therapy—you can gradually refine your topic into a more specific area of inquiry. This approach ensures that your creativity, critical thinking, and understanding of the subject remain at the center of the process. AI serves as a supportive tool to enhance your efforts rather than dictate them.

Let me highlight two other ways AI might be helpful. Students often struggle to come up with unique or original ideas. For your research project, we want you to explore a topic that genuinely interests you, but we also encourage you to approach it from a fresh perspective—one that hasn’t been explored countless times before.

AI can be a valuable tool to help you navigate this process of generating unique ideas. If you struggle in this area, one of the best suggestions I can make is to experiment with AI as it relates to your topic. Take time to sit down with the AI engine of your choice and engage in a back-and-forth exploration. You might start by asking AI what has or hasn’t been researched concerning your topic or request suggestions for under explored angles. Remember however, that one of the shortcomings of AI is, at times, producing inaccurate or incomplete information. Just because AI states a subject matter hasn’t been investigated doesn’t make it so. It will be up to you to do the leg work to make sure you are adding something new to the current literature.

Use AI to spark ideas, discover gaps in the literature, and refine your focus. Remember, the goal is to utilize AI as a supportive resource to inspire your creativity and critical thinking, not to rely on it solely as the source of your ideas. AI may also be used to locate articles, allowing you to start reading information related to your topic.

Dr. Christie Knight

How do you feel about your topic?

Perhaps you have started with a specific population in mind, such as youth who identify as LGBTQ or visitors of a local family clinic. Perhaps you choose to start with a specific social problem, such as father involvement after divorce, or social policy or program, such as free school lunches. Alternately, maybe there are interventions that you are interested in learning more about, such as the Gottman Method or applied behavior analysis. Your motivation for choosing a topic does not have to be objective. Just because you think a policy is wrong or a group is being marginalized, for example, does not mean that your research will be biased. Instead, it means that you must understand how you feel, why you feel that way, and what would cause you to feel differently about your topic. Recognizing our own feelings towards any topic we might want to research is important for being as objective as possible, as well as knowing where we might be prone to injecting our own ideas (which can be both a strength and weakness).

Start by asking yourself how you feel about your topic. Be totally honest and ask yourself whether you believe your perspective is the only valid one. Perhaps yours isn’t the only perspective, but do you believe it is the wisest one? The most practical one? How do you feel about other perspectives on this topic? If you are concerned that you may design a project to only achieve answers that you like and/or cover up findings that you do not like, then you must choose a different topic. For example, a researcher may want to find out whether there is a relationship between intelligence and political affiliation while holding the personal bias that members of their own political party are the most intelligent. Their strong opinion would not be a problem by itself; however, if they feel rage when considering the possibility that the opposing party’s members are more intelligent than those of their own party, then the topic is probably too conflicting to use for unbiased research.

It is important to note that strong feelings about a topic are not always problematic. In fact, some of the best topics to research are those that are important to us. What better way to stay motivated than to study something that you care about? You must be able to accept that people will have a different perspective than you do and try to represent their viewpoints fairly in your research. If you feel prepared to accept all findings, even those that may be unflattering to or distinct from your personal perspective or experience, then perhaps you should intentionally study a topic about which you have strong feelings because you’ll bring a level of passion that is important for sustaining interest.

Kathleen Blee (2002) has taken this route in her research. Blee studies hate movement participants, people whose racist ideologies she studies but does not share. You can read her accounts of this research in two of her most well-known publications, Inside Organized Racism and Women of the Klan. Blee’s research is successful because she was willing to report her findings and observations honestly, even those about which she may have strong feelings. Unlike Blee, if you conclude that you cannot accept or share findings with which you disagree, then you should study a different topic. Knowing your own hot-button issues is an important part of self-knowledge and reflection in social work.

Family scientists and many other social scientists often use personal experience as a starting point for what topics are interesting to cover. As we’ve discussed here, personal experience can be a powerful motivator to study a topic in detail. However, researchers should also be mindful of their own mental health during the research process. Someone who has experienced a mental health crisis or traumatic event should approach researching related topics with caution. There is no need to retraumatize yourself or jeopardize your mental health for a research paper. For example, a student who has just experienced domestic violence may want to know about Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. While the student might gain some knowledge about potential treatments for domestic violence, they will likely have to read through many stories and reports about domestic violence. Unless the student’s trauma has been processed in therapy, conducting a research project on this topic may negatively impact the student’s mental health. Nevertheless, she will acquire skills in research methods that will help her understand the EMDR literature and whether to begin treatment in that modality.

Whether you feel strongly about your topic or not, you will also want to consider what you already know about it. There are many ways we know what we know. Perhaps your mother told you something is so. Perhaps it came to you in a dream. Perhaps you took a class last semester and learned something about your topic there, or you may have read something about your topic in your local newspaper or in People magazine. We discussed the strengths and weaknesses associated with some of these different sources of knowledge in Chapter 1, and we’ll talk about other sources of knowledge, such as prior research, in the next few sections. For now, take some time to think about what you know about your topic from all possible sources. Thinking about what you already know will help you identify any biases you may have, and it will help as you begin to frame a question about your topic.

The Researcher’s Toolkit: How I Apply What I Teach

When I was younger, I was sure of one thing—I was going to grow up and become an FBI agent. And that wasn’t just a passing idea; it was the plan. Even as I entered college, that dream stayed with me. So you can imagine my excitement when, one day while walking across campus, I saw a flyer that (at least in my memory) read something like this: “Come and be taught and gain all the knowledge you have ever wanted and have all your childhood dreams fulfilled by receiving instruction from a real, in-the-flesh FBI agent.”

I was sold. I signed my name at the bottom of the sign-up sheet.

In reality, what I had signed up for was a 36-week training program to become a rape crisis advocate, with a grand total of about two hours taught by a real-life FBI agent. But something surprising happened. Instead of disappointment, I discovered a calling I hadn’t expected.

Over the next four years, I worked directly with survivors of sexual violence in emergency room settings. I sat with them through some of the most challenging moments of their lives. And somewhere along the way, my dream of becoming an FBI agent quietly faded. It was replaced by a more personal and powerful passion for advocacy, prevention, and research.

That experience became the foundation of my career. I’ve since written grants to support prevention efforts on high school and college campuses, helped train upstanders, developed educational programs, and spent a decade researching how to stop sexual violence before it starts. My work focused on understanding perpetrators, promoting upstander intervention, and supporting survivors.

What students can take away from this is simple: Passion doesn’t always start the way you think it will. Sometimes, a flyer you take too literally or a training that veers far from your original goals will shape your life’s work. Stay open to the unexpected. The field of research—and the people we serve—need your curiosity, empathy, and willingness to follow the work where it leads you. – Dr. Knight

“Me-search” and Research

Generally, we don’t propose research questions on topics that have zero relevance to our own lives or work (or else why would we even be interested?). However, there’s a difference between studying something you have feelings about and studying something you have personally experienced. Sometimes, research on one’s own experiences or identity is called “me-search”—this has been used as both an insult and simply as a descriptor, but it is worth noting that there are both pros and cons to doing research like this.

A pro is that you’re likely highly passionate and motivated to do the research, which is useful for the long slogs of reading, writing, and thinking that good research requires. It also means that you’ll likely have tons of questions already in your mind because this is a topic you’ve probably thought about quite a bit before, and you might have insider knowledge about the experience that can help you see where prior research is lacking or can generate new directions for inquiry.

The cons are similar to those described above: you likely already have strong feelings about the topic and may find it challenging to have an open and unbiased mind as you ask questions and seek answers regarding your topic. It’s okay to have biases (we all do) as long as you openly acknowledge them, work to reduce their impact wherever possible, and remove yourself from cases where you are unable to approach a topic fairly because of your biases. Again, you also need to protect yourself and consider what parts of the topic may be too close to your heart for you to work with them safely and fairly.

The Researcher’s Toolkit: How I Apply What I Teach

Dr. Arocho’s Me-search Story:

Me-search became very real to me when I was a graduate student branching out in my research topics. For the first few years of my scholarly career, I’d studied things like parent education or marriage expectations. However, I’d wanted to develop some skills in a new area. I’m a donor-conceived person, meaning my parents used donor sperm to conceive me. I didn’t know I was donor-conceived until I was a teenager and my dad (the man who raised me but was not my biological father) had died. Finding out was traumatic for me, and for a long time I couldn’t discuss anything about donor conception without basically falling apart. In graduate school, I met researchers who were studying topics about donor conception, and I decided I wanted to get involved when they invited me to join them on a study. This particular study was looking at the reasons parents using donor conception do or don’t tell their children about their status and the associated outcomes for the children. Since I had experienced a fairly traumatic disclosure that happened pretty late in my adolescence, I expected that the children in our study with similar disclosure experiences would have similarly harmful outcomes like I had. When the results came back, however, it appeared that most of the kids were really doing fine whether their parents had disclosed or not. I was incredulous! How could this be? I was actually upset quite a bit by the initial results. The research team checked our findings, and they held, so we had to figure out how to interpret what we were seeing. I eventually was able to accept the findings and make sense of them both in a scientific way, and in light of my own experiences with the topic. Following that study, I continued to dabble in donor conception research, but I realized that studying disclosure was too close to home for me; I still wanted to contribute to my community, but I had to do it with other questions in the same topic. I still do research on donor conception and more broadly on fertility treatments, but I do have to be aware of my own reactions and emotional state. Instead of disclosure, I focus my research efforts on other areas, like the demography of donor-conception families and the educational needs of prospective donor-conception parents. These are topics I’m still very passionate about, and I have a unique perspective given my personal experience, but I have to constantly ask myself if my personal experiences are clouding my perceptions (it helps that I work with a diverse team of researchers, some with donor-conception experience and some without, so that we can check each other’s biases when needed).

What do you want to know?

Once you have a topic, begin to think about it in terms of a question. What do you really want to know about the topic? As a warm-up exercise, try dropping a possible topic idea into one of the blank spaces below. The questions may help bring your subject into sharper focus and provide you with the first important steps towards developing your topic.

- What does ___ mean? (Definition)

- What are the various features of ___? (Description)

- What are the component parts of ___? (Simple analysis)

- How is ___ made or done? (Process analysis)

- How should ___ be made or done? (Directional analysis)

- What is the essential function of ___? (Functional analysis)

- What are the causes of ___? (Causal analysis)

- What are the consequences of ___? (Causal analysis)

- What are the types of ___? (Classification)

- How is ___ like or unlike ___? (Comparison)

- What is the present status of ___? (Comparison)

- What is the significance of ___? (Interpretation)

- What are the facts about ___? (Reportage)

- How did ___ happen? (Narration)

- What kind of person is ___? (Characterization/Profile)

- What is the value of ___? (Evaluation)

- What are the essential major points or features of ___? (Summary)

- What case can be made for or against ___? (Persuasion)

- What is the relationship between _____ and the outcome of ____? (Exploratory)

Building Your Ideas Before Bringing in AI

Show

Answering these questions before using AI to explore your topic of interest is advisable. This approach allows YOU to control your research and critical thinking, ensuring that AI enhances rather than dictates your direction. By independently defining, describing, and analyzing your topic, YOU build a strong foundation of understanding, allowing AI to function as a supplemental tool rather than the primary source of information. By answering these structured questions, YOU identify what you already know and where gaps exist. This approach allows YOU to direct AI toward specific areas of interest rather than relying on AI to generate broad, unfocused information. This approach encourages critical engagement with AI responses, enabling you to compare AI insights with your own reasoning and research, ultimately strengthening your analytical skills.

Additionally, this method helps YOU develop independent research skills by using AI to enhance rather than replace your ability to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information. By first answering these guiding questions, YOU practice research and reasoning before leveraging AI for refinement or deeper exploration. It also prevents over-reliance on AI, ensuring that YOU remain in control of your topic rather than allowing AI to shape your direction in unintended ways. Using these questions as a pre-AI thinking exercise ensures YOU lead the research process, using AI purposefully to deepen, verify, or refine your understanding.

Dr. Christie Knight

Take a minute right now and write down a few questions you want to answer from some of the topics you listed earlier. Even if it doesn’t seem perfect, everyone needs a place to start. Make sure your potential questions are relevant to family science. You’d be surprised how much of the world that encompasses. It’s not just research on marriage, parents, or therapy. Family science is the scientific study of families and close interpersonal relationships, so there’s a lot of room in that definition for many different kinds of questions. If you’re unsure if your topic fits the expectations of your class, be sure to talk with your professor to understand what they expect and how they can help you with your question. Your question is only a starting place, as research is an iterative process, one that is subject to constant revision. As we progress in this textbook, you’ll learn how to refine your question and include the necessary components for proper qualitative and quantitative research questions. Your question will also likely change as you engage with the literature on your topic. You will learn new and important concepts that may shift your focus or clarify your original ideas. Trust that a strong question will emerge from this process.

References

- Action Network for Social Work Education and Research (n.d.). Advocacy. Retrieved from: https://www.socialworkers.org/Advocacy/answer

- Blee, K. (2002). Inside organized racism: Women and men of the hate movement. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; Blee, K. (1991). Women of the Klan: Racism and gender in the 1920s. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Pain, E. (2016, March 21). How to (seriously) read a scientific paper. Science. Retrieved from: http://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2016/03/how-seriously-read-scientific-paper