Why Read Prior Research?

Reading and citing other people’s research is the conversation part of science. It’s what allows researchers to build on each other’s work and reach new heights rather than re-inventing the wheel each time they want to study something new. Let’s think for a moment about how we can engage with prior research when we are considering proposing our own questions and ideas.

Be a conversationalist!

Imagine you’re eating a meal with a group of friends. You leave the room for a moment, and when you return, you notice that most of the group is deep in conversation on a topic you’re interested in and know a little about. What do you do?

- A. Jump in with your opinion right away

- B. Listen and observe for a few moments, then offer your thoughts based both on what you know and what you’ve heard other people say

- C. Listen and observe, but never speak up

If you answered B, you’re already in the right state of mind for reading and contributing to research. Even if you didn’t answer B, though, you can develop the skills to contribute by thinking about how the practices of listening and contributing best fit together. Jumping straight into the middle of a conversation without listening to what’s already been and being said (Option A) can lead to some embarrassing situations or, at the very least, wasted breath if what you’re saying has already been said and the group has moved on. On the contrary, always listening and never contributing is a safe way to live (Option C), but you never get to push the boundaries and drive the conversation in a new direction. Option B is the best approach for when you want to contribute your new idea but want to do it respectfully and in a way that actually helps expand everyone’s thinking in the process.

Even if you never do research in real life, understanding how an individual research study can fit into the broader conversation of science will help you better understand the contribution of any particular study you read. No one study can tell us everything we need to know about something; rather, seeing the literature as a whole is like listening to the conservation and the best way to fully grasp the body of knowledge on a given topic.

Searching for Literature

The first step in reading research is finding something worth reading! To do this, we need to learn about searching for and evaluating sources of information. We often talk about “the literature” as the space that holds the knowledge we need. For our purposes “the literature” is a collection of all of the relevant written sources on a topic.

Information does not exist in the environment like some kind of raw material, rather it is produced by individuals working within a particular field of knowledge who use specific methods for generating new information. Disciplines consume, produce, and disseminate knowledge. Looking through a university’s course catalog gives clues to disciplinary structure. Fields such as political science, biology, history, and mathematics are unique disciplines, as are social work, sociology, family science, and many others. Each has its own logic for how and where new knowledge is introduced and made accessible.

You will need to become comfortable with identifying the disciplines that might contribute information to any search. When you do this, you will also learn how to decode the way people talk about a topic within certain disciplines. This will be useful when you begin a review of the literature in your area of interest.

For example, think about the disciplines that might contribute information to a topic such as the role of sports in society. Try to anticipate the type of perspective each discipline might have on the topic. Consider the following types of questions as you examine what different disciplines might contribute:

- What is important about the topic to the people in that discipline?

- What is most likely to be the focus of their study about the topic?

- What perspective would they be likely to have on the topic?

In this example, let’s identify a few disciplines that have something to say about the role of sports in society: for this example, let’s consider nursing, social work, and family science. What would each of these disciplines raise as key questions or issues related to that topic? A nursing researcher might study how sports affect individuals’ health and well-being, how to assess and treat sports injuries, or the physical conditioning required for athletics. A social work researcher might study how schools privilege or punish student athletes, how athletics impact social relationships and hierarchies, or the differences between boys’ and girls’ participation in organized sports. Family scientists might look at how families use sports for family leisure, or how children’s participation in sports is supported by parental behaviors, or how sport involvement is associated with important child development outcomes. In this example, we see that a single topic can be approached from many different perspectives depending on how the disciplinary boundaries are drawn and how the topic is framed. Even when one is working from a particular disciplinary view, however, it is useful to be aware of the other discipline’s work on the topic. For example, both the social work and family scientist should be aware of the nursing literature, as they could better appreciate the physical toll that sports take on athletes’ bodies and how that may interact with other issues. An interdisciplinary perspective is usually a more comprehensive perspective.

Types of sources

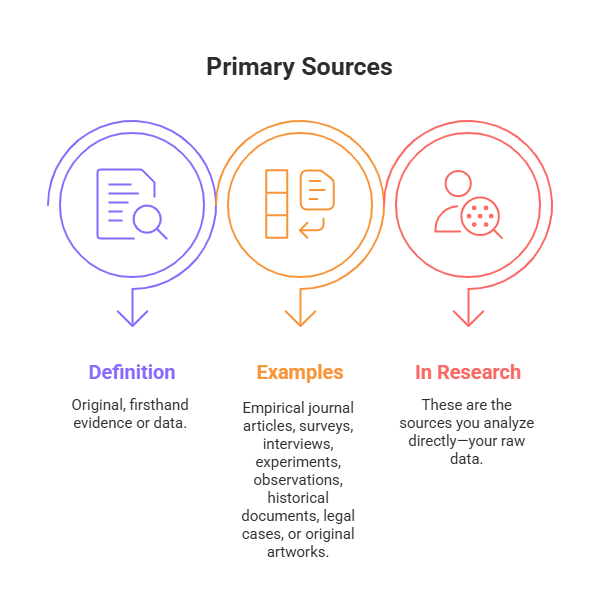

Secondary vs. Primary Sources

“The literature” consists of the published works that document a scholarly conversation on a specific topic within and between disciplines. In “the literature,” you will find documents that explain the background of your topic. You will also find controversies and unresolved questions that can inspire your own project. At this point in your schooling, you’ve almost certainly been given an assignment that required “peer-reviewed journal articles.” But what are those exactly? How do they differ from news articles or encyclopedias? This section of the text will help you to differentiate the different types of literature.

First, let’s discuss periodicals. Periodicals include journals, trade publications, magazines, and newspapers. While they may appear similar, particularly online, each of these periodicals has unique features designed for a specific purpose. Magazine and newspaper articles are usually written by journalists. They are intended to be short and understandable for the average adult, they contain color images and advertisements, and they are designed as commodities to be sold to an audience. Magazines may contain primary or secondary literature depending on the article in question. An article that is a primary source would gather information as an event happened, like an interview with a victim of a local fire, or relate original research done by the journalists, like the Guardian newspaper’s The Counted webpage which tracks how many people were killed by police officers in the United States (The Guardian, n.d.)

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

You may be wondering if magazines are acceptable sources of information in a research methods course. Most likely, they are not. There are some exceptions like the Guardian page mentioned above or breaking news about a policy or community, but in general it’s best to avoid magazines and newspapers because most of the information they publish is secondary literature. Secondary sources interpret, discuss, and summarize primary sources. Often, news articles will summarize a study done in an academic journal. Your job as a student of research is to read the original source of the information, in this case, the academic journal article itself. Journalists are not scientists. If you have seen articles about how chocolate cures cancer or how drinking whiskey can extend your life, you should understand how journalists can exaggerate or misinterpret results. Careful scholars will critically examine the primary source, rather than relying on someone else’s summary. Many newspapers and magazines also contain opinion articles, which are even less reputable, as the author will choose facts to support their viewpoint and exclude facts that contract their viewpoint. Nevertheless, newspaper and magazine articles are excellent places to start your journey into the literature, as they do not require specialized knowledge to understand and may inspire deeper inquiry.

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

Unlike magazines and newspapers, trade publications may take some specialized knowledge to understand. Trade publications or trade journals are periodicals directed to members of a specific profession. They often have information about industry trends and practical information for people working in the field. Trade publications are somewhat more reputable than newspapers or magazines because the authors are specialists on their field. NASW News is a good example of a trade publication in social work, published by the National Association of Social Workers. Its intended audience is social work practitioners who want to know about important practice issues. They report news and trends in a field but not scholarly research. They may also provide product or service reviews, job listings, and advertisements. CFLE Network is similar for Certified Family Life Educators and is published through the National Council on Family Relations.

So, can you use trade publications in a formal research proposal? Again, it’s likely that they will not be useful to you, as a main shortcoming of trade publications is their lack of peer review. Peer review refers to a formal process in which other esteemed researchers and experts ensure your work meets the standards and expectations of the professional field. While trade publications do contain a staff of editors, the level of review is not as stringent as academic journal articles. On the other hand, if you are doing a study about practitioners, then trade publications may be quite relevant sources for your proposal. As illustrated below, peer review is the part of the publication cycle that acts as the gate-keeper to ensure that only top-quality articles are published. While peer review is far from perfect, the process provides for stricter scrutiny of scientific publications.

In summary, newspapers and other popular press publications are useful for getting general topic ideas. Trade publications are useful for practical application in a profession and may also be a good source of keywords for future searching. Scholarly journals are the conversation of the scholars who are doing research in a specific discipline and publishing their research findings.

Gold Standard: Journal Articles

As you’ve probably heard by now, academic journal articles are regarded as the most reputable sources of information, particularly in research methods courses. Journal articles are written by scholars with the intended audience of other scholars (like you!) interested in the subject matter. The articles are often long and contain extensive references for the arguments made by the author. The journals themselves are often dedicated to a single topic, like child development, marriage, or parenting and include articles that seek to advance the body of knowledge about their chosen topic.

Most journals are peer-reviewed or refereed, which means a panel of scholars reviews articles to decide if they should be accepted into a specific publication. Scholarly journals provide articles of interest to experts or researchers in a discipline. An editorial board of respected scholars (peers) reviews all articles submitted to a journal. Editors and volunteer reviewers decide if the article provides a noteworthy contribution to the field and if it should be published. For this reason, journal articles are the main source of information for researchers and for literature reviews. You can tell whether a journal is peer reviewed by going to its website. Usually, under the “About Us” section, the website will list the editorial board or otherwise note its procedures for peer review. If a journal does not provide such information, you may have found a “predatory journal.” These journals will publish any article—no matter how bad it is—as long as the author pays them. Not all journals are created equal!

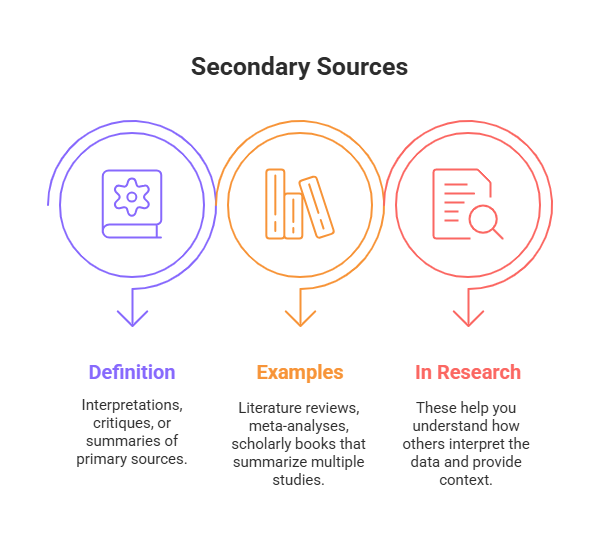

A kind of peer review also occurs after publication. Scientists regularly read articles and use them to inform their research. By citing a past journal article in their own work, scientists show how that study informed their own and build on the knowledge gained. Often, a study’s citation count (which you can see by searching a source in Google Scholar and looking at the Cited By feature, as shown below) can help you see if a study has been well-received by the field. Note, however, that it’s also possible a study has been cited because a new study has identified a problem with the original one – numbers alone don’t indicate quality.

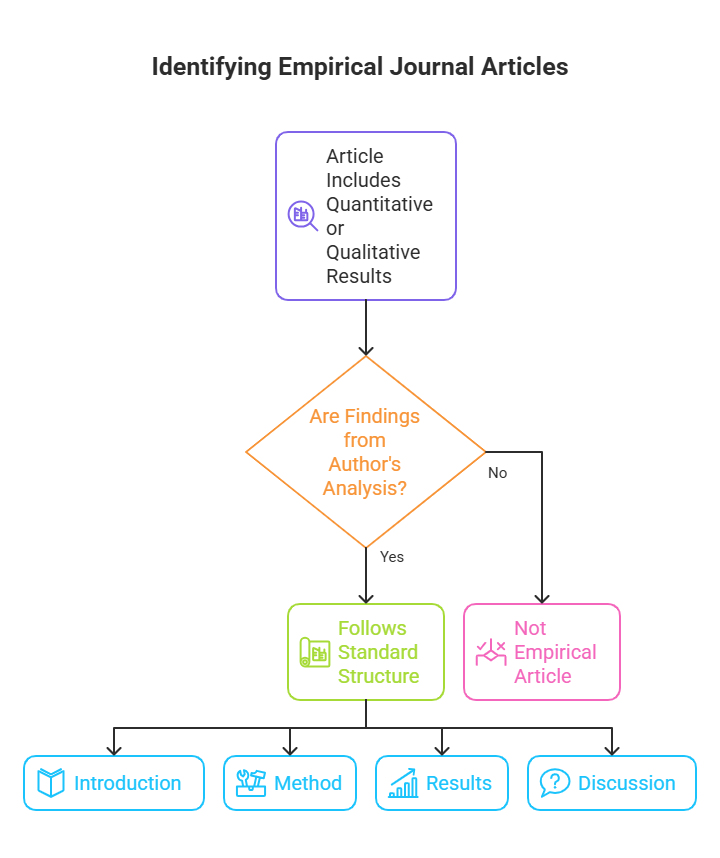

Journal articles fall into a few different categories. Empirical articles apply theory to a behavior and reports the results of a quantitative or qualitative data analysis conducted by the author. Just because an article includes quantitative or qualitative results does not mean it is an empirical journal article. Since most articles contain a literature review with empirical findings, you need to make sure the findings reported in the study are from the author’s own analysis. Fortunately, empirical articles follow a similar structure—introduction, method, results, and discussion sections appear in that order. While the exact headings may differ slightly from publication to publication and other sections like conclusions, implications, or limitations may appear, this general structure applies to nearly all empirical journal articles.

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

Theoretical articles, by contrast, do not follow a set structure. They follow whatever format the author finds most useful to organize their information. Theoretical articles discuss a theory, conceptual model, or framework for understanding a problem. They may delve into philosophy or values, as well. Theoretical articles help you understand how to think about a topic and may help you make sense of the results of empirical studies.

One type of article is not better than another, but they do serve different purposes. You’ll likely want a mix of these articles to help you build your knowledge of a given topic and to help you write your literature review, which will describe the state of knowledge around a question you’re interested in.

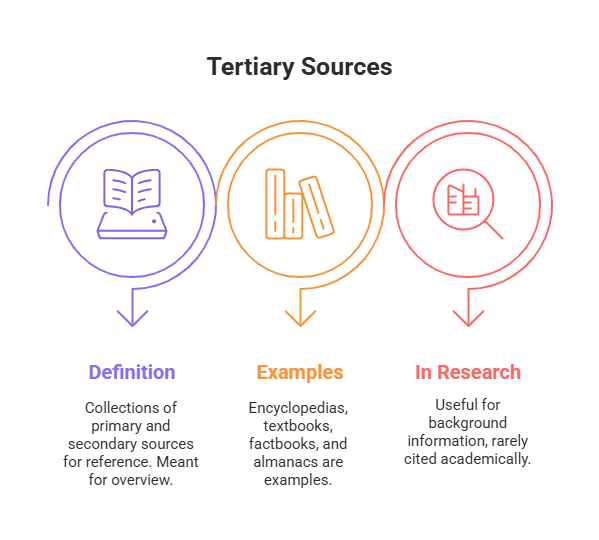

Tertiary sources

As mentioned earlier, newspaper and magazine articles are good places to start your search, though they should not be the end of your search. Another source that students commonly flock to is Wikipedia. Wikipedia is a marvel of human knowledge, as anyone can contribute to the digital encyclopedia. The entries for each Wikipedia article are overseen by skilled and specialized editors who volunteer their time and knowledge to making sure their articles are correct and up to date. Wikipedia is an example of a tertiary source. We reviewed primary and secondary sources in the previous section. Tertiary sources synthesize or distill primary and secondary sources. Examples of tertiary sources include encyclopedias, directories, dictionaries, and textbooks! Tertiary sources are an excellent place to start but are not a good place to end your search. A student might consult Wikipedia to get a general idea of the topic, but for learning in-depth information (and for citing sources in an assignment), they should dig much deeper.

* This image was created using napkin.ai; however, the concept, design direction, and creative vision were conceived by Dr. Knight

You might, in your internet searching, also come across articles that are published on blogs or other websites. These are likely to be the least helpful type of source we’ve talked about so far as there is no way to verify the accuracy of these posts or sometimes even the authority of the author. If you come across one that is interesting to you and you feel helps you gather information for your study idea, then take a look at the references and sources given by the blog, and go read those yourself. Similarly, if you find a Wikipedia article on your topic, follow the sources used in the article back and read those yourself. Through this back-tracking exercise, you may actually find helpful primary sources of information. Secondary and tertiary sources are great places to begin gathering background information on a topic, but as your study of the topic progresses towards your research project, you will have to begin using primary sources, like those that (should be) cited in the secondary and tertiary sources you find. Academic journal articles are one of the primary sources that we will discuss the most in this textbook, as they are an excellent source to use in formal research papers. However, it is important to understand how other types of sources can be utilized as well.

Other potential sources of information

Books contain important scholarly information. They are particularly helpful for theoretical, philosophical, and historical inquiry. You can use books to learn definitions and key concepts, to identify keywords, and to find additional resources for further information. They will also help you to understand the scope of the topic, its underlying foundations, and how the topic has developed over time.

You may notice that some books contain chapters that resemble academic journal articles. These are called edited volumes, and they contain articles that may not have made it into academic journals or foundational articles that are republished in the book. Edited volumes are considered less reputable than journal articles, as they do not have as strong of a peer review process. However, papers in social science journals will often include references to books and edited volumes as part of a larger list of reference sources.

In addition to peer-reviewed academic journal articles and books, conferences are another great source of information. The papers presented at conferences are sometimes published in a volume called a conference proceeding, which highlights current discussions in a discipline and can lead you to scholars who are interested in specific research areas. If you are looking to use a conference proceeding as a source for your research paper, it is important to note that several factors can make them particularly difficult to find. Papers that are delivered at professional conferences are not always fully published in print or electronic form. The abstract of a paper may be available; however, the full paper may only be available to the author(s). If you have any difficulty accessing a conference proceeding or paper, ask a librarian for assistance.

Another source of information is the gray literature, which is research and information released by non-commercial publishers, such as government agencies, policy organizations, and think-tanks. Gray literature can be especially helpful when you’re looking for up-to-date statistics on a topic, as this kind of source can often be published much faster than a traditional peer-reviewed journal article. The National Center for Family and Marriage Research (https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr.html) is one such source of recent information about families. The Centers for Disease Control website (https://www.cdc.gov/) can be helpful for understanding the prevalence of social problems like mental illness and child abuse. There are many other groups out there that publish helpful gray literature! However, it is important to note that there are potential limitations to using gray literature as a source, such as the potential for biased information. Typically, think tanks and policy organizations have a specific viewpoint that they support. For example, there are conservative, liberal, and libertarian think tanks and policy organizations may be funded by private businesses to push a given message to the public. On the other hand, government agencies are generally more objective, though they may be less critical in their opinions of government programs than other sources. The main shortcoming of gray literature is the lack of peer review that is found in academic journal articles, though many gray literature sources are of good quality If in doubt, talk to librarians or scholars in your field to get their take on a given source as well as the group that produced it.

Additional sources of gray literature include dissertations and theses, which are research projects that students complete in the processes of receiving doctoral or master’s degrees. These two kinds of sources are often quite rich, and they usually contain extensive reference lists that you can scan for further resources, however they are considered gray literature because they are not peer reviewed. The accuracy and validity of the paper itself may depend on the school that awarded the degree to the author. If you come across a dissertation that is relevant, it is a good idea to read the literature review and plumb the sources the author uses in your literature search. However, the data analysis from these sources is considered less reputable as it has not passed through peer review yet. Many students who complete these documents do go on to publish them (or parts of them) in traditional peer-reviewed outlets after they graduate. Consider searching for journal articles by the author to see if any of the results passed peer review. You will also be thankful that journal articles are much shorter than dissertations and theses!

Final Thoughts

As you think about each source, remember:

All information sources are not created equal. Sources can vary greatly in terms of how carefully they are researched, written, edited, and reviewed for accuracy. Common sense will help you identify obviously questionable sources, such as tabloids that feature tales of alien abductions, or personal websites with glaring typos. Sometimes, however, a source’s reliability—or lack of it—is not so obvious. To evaluate your research sources, you will use critical thinking skills consciously and deliberately (Crowther et al., n.d., para. 6)

While each of these sources is an important part of how we learn about a topic, your research should focus on finding academic journal articles about your topic. These are the primary sources of the research world. While it may be acceptable and necessary to use other primary sources—like books, government reports, or an investigative article by a newspaper or magazine—academic journal articles are preferred. Finding these journal articles is the topic of the next section.

References

Crowther, K., Cutright, L, Gilbert, N., Hall, B., Ravita, T., & Swenson, K. (n.d.). Evaluating and processing your sources. LibreTexts Humanities. https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Composition/Introductory_Composition/Successful_College_Composition_(Crowther_et_al.)/4%3A_Writing_a_Research_Paper/4.5%3A_Evaluating_and_Processing_Your_Sources

The Guardian (n.d.). The counted: People killed by police in the US. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2015/jun/01/the-counted-police-killings-us-database

Image Attributions

Yahoo news portal by Simon CC-0

Research journals by M. Imran CC-0

Books door entrance culture by ninocare CC-0

Media Attributions

- Cherlin Scholar