15 Graduate Teaching Communities of Practice: Fostering a Sense of Belonging and Professional Development for Graduate Students, by Graduate Students

April Athnos; Tianyi Kou-Herrema; Matthew Langley; Emile Oshima; Harrison Parker; Hima Rawal; Olivia Wilkins; Alexandra Lee; Seth Hunt; Ellen Searle; and Nathalie Marinho

Key Takeaways

-

Communities of Practice provide explicit formal recognition for teaching work and serve as a network of pedagogical resources.

-

Communities of Practice create a safe space and a strengthened sense of community.

-

Communities of Practice can be formed anywhere to meet any set of needs but always thrive with members’ agency and institutional support.

Introduction

For many, the graduate school experience is defined by intense periods of coursework, research development, and first-time teaching responsibilities. While study groups and research teams are common community practices to collaborate and share workloads, graduate student instructors (GSIs) often operate more independently. Many graduate students discover a passion for teaching but lack access to a network of teaching professionals to learn from, or they encounter difficulty creating a structured plan toward their teaching goals. Moreover, graduate students may feel isolated in their interest in teaching, especially within research-intensive institutions that systematically value research output over teaching development.

In our experience, one way to overcome these challenges is through graduate student teaching and learning communities of practice. A Community of Practice (CoP) is a group of “By listening to what other people had to say about their experiences, and through multiple discussions, I was able to reflect on myslef as both a student and a teacher.”

– Postdoc in Geophysics, Caltechpeople who share a concern or passion for something they do and learn how to improve through regular interactions (Wenger & Wenger-Trayner, 2017). CoPs bring together graduate students

in a collaborative, empathetic, and non-judgmental space (subsequently referred to as a ‘safe space’) within our universities to expose members to effective pedagogical practices, give explicit recognition for teaching work, and reflect on lived experiences as student-educators.

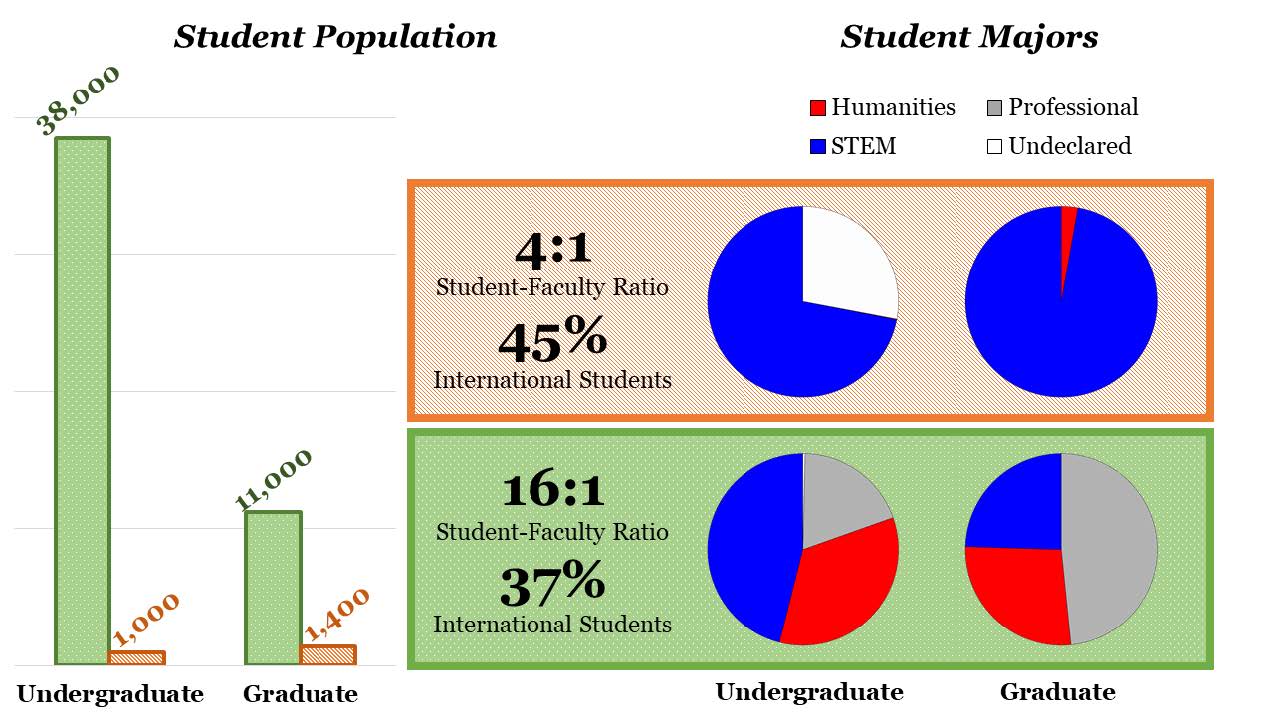

We hail from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and Michigan State University (MSU): two very different institutions, yet both of which host graduate student CoPs. To provide some context, Figure 1 summarizes the student population and distribution of majors at each of our schools. Caltech (striped orange) is a small private university with less than 2,500 students, more than half of which are graduate students. In contrast, MSU (dotted green) is a large public university with nearly 50,000 undergraduate and graduate students in total. As shown in the figure, both Caltech and MSU attract students and researchers from all over the globe, bringing together people from many backgrounds and with diverse interests. Caltech is divided into six academic divisions, five of which focus on science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields, and undergraduates do not declare a major until the end of their freshmen year. MSU offers a broader spectrum of concentrations that encompass the arts and humanities, as well as professional degrees in business, law, and medicine. The pie charts visualize the distribution of students across these two distinct organizational structures by categorizing degrees under “STEM”, “Humanities”, or “Professional”.

Figure 1. Summary of the institutional differences between Caltech (striped orange) and MSU (dotted green). Student majors are defined and categorized differently across the two schools, so we use color to visualize the overall distribution of STEM, humanities, and professional schooling (medical, business, etc.). Sources: Caltech Registrar’s Office, 2021; Michigan State University Office of the Registrar, 2021.

In this chapter, we provide an overview of the theoretical underpinnings of CoPs to understand why they provide a viable model for supporting the development of GSIs. We share our experiences as members of two GSI CoPs by explaining the foundation of each group and characterizing the specific formal and informal benefits associated with our communities. At the end of this chapter, we offer our suggestions and encourage readers to consider starting a CoP at their own institutions.

Communities of Practice as a Social Learning Theory-Based Approach to Supporting Graduate Student Instructors

The concept of a Community of Practice (CoP) emerged as a way to understand how learning happens outside of direct instruction (Wenger & Wenger-Trayner, 2017) and can provide a useful framework for understanding how GSIs may learn about teaching in the absence of, or in addition to, traditional training. Graduate students often receive only limited formal training about effective instructional practices prior to becoming instructors (Brownell & Tanner, 2012). Additionally, since faculty at research-focused institutions are primarily engaged in research activities, graduate students may feel the need to seek out mentors other than their primary advisor to support their development as GSIs (Lechuga, 2011). A CoP fills these gaps in formal training and mentorship by providing a space for “apprentices and more experienced workers” to grow together as educators (Mercieca, 2017, p. 4). Therefore, we have chosen to use the CoP framework to make sense of our activities and how those activities relate to the development of GSIs as effective teachers.

There are three defining features that are foundational to the initiation and maintenance of a CoP (Mercieca, 2017; Wenger, 1998):

- a shared domain, which captures the common interests or focal concerns that motivate individuals to join the CoP (Wenger, 1998). In our CoPs, the domain is a mutual interest in learning how to effectively teach at the post-secondary level.

- a common practice, or “a repertoire of resources the community has accumulated through its history of learning” (Wenger, 2010, p. 2). This shared repertoire can include experiences, tools, and ways of addressing recurring problems. In our CoPs, we often share the challenges we face in our courses to communally develop potential solutions.

- a sense of community, fostered by allowing members to build relationships and interact informally on a regular basis (Wenger, 1998). In our CoPs, we leave ample time after events to connect with each other and share interests outside the realm of teaching.

These three defining features of CoPs help GSIs develop a professional identity and sense of competence (Wenger, 1998). When GSIs participate in a CoP, they learn new skills that lead to increased job performance and, in turn, a greater sense of identity as a professional. For example, if a GSI observes an experienced community member modeling an instructional strategy and then successfully replicates that strategy in their own practice, it will affirm their professional identity and sense of competence as an instructor. Therefore, participating in a CoP is one way that new graduate instructors can gain a sense of competence as educators—a key predictor of teaching quality and undergraduate student success (Fong et al., 2019). Furthermore, CoP membership facilitates a sense of belonging with other graduate student instructors because of the shared experiences of developing their teaching practice. Since belonging is associated with positive outcomes, including motivation, persistence, and achievement (Walton et al., 2012), CoPs may enhance the achievement of graduate student instructors as students themselves.

In the next section, we will highlight our shared domains by telling the origin stories of the two CoPs at our institutions. We also discuss how common practices confer formal benefits to our community members, and then describe how the sense of community built within our CoPs provides substantial informal benefits.

Different Locations, Shared Domains: Foundation of the CoPs

As members of two distinct CoPs (Figure 1), we can identify many shared features of our respective communities despite the differences in their origins. To provide context for the benefits that are common across our CoPs, we describe the respective histories of each one below and provide characteristics in Table 1.

The Caltech Project for Effective Teaching (CPET)

CPET is a group of graduate students and postdoctoral scholars dedicated to improving our teaching skills and helping others do the same. CPET was founded in 2007 as a graduate student club to create a network of peers interested in teaching at an institution where STEM research productivity is widely considered the primary responsibility of graduate students. Our community fosters a strong sense of belonging for many who have a passion for teaching. Graduate students and postdoctoral scholars appreciate the opportunity to join a group like CPET that believes that teaching, mentoring, and public outreach are essential to the graduate student experience.

CPET joined the Caltech Center for Teaching, Learning & Outreach (CTLO) in August 2012 at the time of CTLO’s founding. This earned CPET institutional buy-in, administrative support, and pedagogical expertise. Even with this additional support, CPET retained its original mission of being a community driven by graduate students for graduate students. Currently, we are led by two graduate student co-directors and advised by the CTLO’s Associate Director for University Teaching.

Our graduate co-directors work with CTLO staff and other campus offices to organize events, facilitate certificate programs, and curate a useful collection of pedagogical resources. Before the pandemic, we hosted in-person events such as small-group discussions, seminars with invited speakers, targeted workshops, and socials centered around evidence-based pedagogical topics. These events are intended to spread general awareness of pedagogical topics and aid current instructors. The topics of our events range from the concrete, like active learning techniques and building inclusive classrooms, to the abstract, like the ethical implications of different assessment methodologies.

Since 2020, in response to the urgent needs and concerns of our community members, we shifted event topics to focus on effective remote and asynchronous learning through the lens of teaching during difficult times. When Caltech returned to in-person instruction in Fall 2021, we led a discussion group on learning in a physically-distanced classroom and covered how to effectively incorporate tools and technologies from the virtual classroom into the physical one. By responding to the unique needs and evolving interests of our graduate student community, CPET provides a space that offers the benefits of community and pedagogical support for GSIs beyond the general support provided by their advisors or Caltech as a whole.

The MSU Graduate Teaching Assistants’ Teaching and Learning Community (GTA TLC)

The GTA TLC grew out of concerns within MSU’s Graduate School following the sudden transition to online instruction in March 2020. The Graduate Student and Postdoctoral Instructional Development Director in charge of GSI preparation, Dr. Stefanie Baier, initiated the program to support GSIs through the COVID-19 pandemic. She organized the first events that brought our community together—Zoom social hours, where we connected, shared our favorite coffee mugs, played virtual games, and talked about ongoing challenges. Given the success of these meetings, the social hours morphed into biweekly virtual lunch meetings where we addressed our online teaching concerns. These regular meetings further evolved into a community of GSIs, instructors, and staff from across campus, where members were able to identify common pedagogical needs and share best practices in teaching and learning.

The GTA TLC supports educator growth through moderated discussions, member-led seminars, and social events. The GTA TLC convenes bi-weekly throughout the year including summer. As of the end of 2021, we organized and facilitated roughly 40 events that attracted more than two hundred GSIs. We advertise our events through channels which include the Graduate School’s GTA listserv, the Graduate School calendar, and Microsoft Teams messages. At the end of each event, we solicit feedback, suggestions, and needs from all participants. A core group of roughly 10-12 members, the GTA Preparation (GTAP) Advisory Group, meets biweekly to integrate feedback into future programming, steer the direction of the group, and plan upcoming events. Both the GTA TLC as a whole and the GTAP Advisory Group are managed in a grassroots collaborative fashion with consensus-based decision making. In the fall of 2020, MSU designated the GTA TLC as a Learning Community under the Office of Faculty and Academic Staff Development.

Our community has expanded its membership well beyond the individuals who joined during the COVID-19 pandemic. The GTA TLC continues to provide community-based learning in hybrid formats to accommodate MSU’s community on campus, those working remotely, and those joining from abroad. Due to the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have yet to host fully in-person events, however, we look forward to blending in-person, virtual, and hybrid events in the future.

Table 1. Comparing qualitative features of the two CoPs featured in this chapter.

|

|

CPET |

GTA TLC |

|

Year Initiated |

2007 |

2020 |

|

# Students Actively Involved |

2 co-directors ~70 participants |

2 co-facilitators & 10 core members ~200 participants |

|

Hallmark Events |

Discussion groups Invited speaker seminars Workshops Socials |

Bi-weekly Lunch and Learn seminars Annual GTA Preparation Program |

|

Certificate Programs |

Certificate of Interest in University Teaching Certificate of Practice in University Teaching |

Sessions count towards fulfillment of competencies for Certificate in College Teaching (CCT) |

|

Website Link |

Common Practice: Formal Benefits of our CoPs

Both of our CoPs benefit members in formal and informal ways. Formal benefits are those with defined objectives and include organized events, teaching resources, and practical training; these formal benefits exemplify the common practice feature of CoPs (Wenger, 2010). In this section, we illustrate the formal benefits of both CoPs by providing concrete examples in three aspects: events, teaching resources, and practical training.

CPET provides pedagogy-focused events that are generally open to all Caltech scholars, often formatted as discussion groups, seminars, or workshops. Discussion groups are small, fishbowl-style conversations about pre-circulated materials on various practical or theoretical topics. These discussions are limited to graduate students and postdocs so these events can serve as a safe space for frank discussions. Seminars feature invited speakers, both internal and external to Caltech, who present on any pedagogical topic, ranging from the specific application of pedagogical theory to a larger scale examination of pedagogical research. Workshops, more than discussions or seminars, focus on tangible skill-building and practice. We are able to cater to the diverse needs and interests of our GSI community by participant polling and highly varying the specificity and amount of active participant engagement in our event programming.

All CPET events use and provide teaching resources for the Caltech GSI community. Discussion events are often centered around articles from publications such as The Chronicle of Higher Education. Furthermore, our events incorporate active learning methodology, facilitate metacognition, and employ transparent techniques to model best practices within our CoP teaching resources. We also record the majority of our seminars to share our content with those who could not participate in real-time and create a repository of CPET content. In some events, participants have created communal living documents with crowd-sourced tips and strategies that can be sent to the community at large.

Many CPET event attendees leave seeking a deeper dive into pedagogical theory and practice. To facilitate this, CPET offers two certificate programs for professional development called the Certificate of Interest in University Teaching and the Certificate of Practice in University Teaching. The former is aimed at introducing participants to pedagogical theory through participation in seminars and reflective journal writing, while the latter focuses on developing teaching skills through the direct application of theory. The programs have different levels of commitment and requirements to accommodate participants in different stages of their career and various levels of overall interest.

The Certificate of Interest in University Teaching typically takes about a year to complete and provides an introduction to various facets of teaching and learning through our events. Throughout the program, participants build a cohesive base of pedagogical knowledge in a way that recognizes and acknowledges their own growth while receiving tailored, pertinent feedback from CPET co-directors. Participants engage in six approved events and write a reflective journal entry for each. The prompts for these journal entries are based on educational theorist David Kolb’s model of experiential learning (Kolb, 2015), which requires participants to reflect on their prior knowledge and experiences related to the event topic, what they learned from the event, the strengths and weaknesses of the material, and how they may apply that material to their own teaching. CPET co-directors respond to the submissions with additional thoughts and supplemental materials relevant to the topics discussed in the reflective journal. The Certificate of Interest culminates in a final reflective summary. Upon successful completion of the Certificate of Interest, participants receive a letter of completion signed by the Dean of Graduate Studies and CTLO and recognition of participation during graduation.

The Certificate of Practice in University Teaching typically takes at least two years to complete and is designed to assist participants in their evolution as instructors by providing a framework for their professional development. It is administered by the Associate Director for University Teaching at the CTLO, as the time commitment is more than can be expected for administration by a student group. Participants in the Certificate of Practice program engage in three major areas: synthesis and application of effective methods for teaching and learning; assessment and implementation of a teaching philosophy; and refinement of pedagogy through feedback and self-evaluation. To achieve these outcomes, participants learn about pedagogy through formal coursework on evidence-based pedagogical practices and techniques. They then complete an iterative process of incorporating effective practices into their teaching and then reflecting on their application experiences. During each step, participants receive, reflect on, and respond to feedback from the Associate Director for University Teaching at the CTLO. Finally, participants prepare and submit a teaching statement and a portfolio of their work from the program, giving the participant deliverables that are applicable to their professional goals. Participants also receive a notation on their transcript recognizing their completion of the Certificate of Practice, a letter of completion signed by the Dean of Graduate Studies and CTLO, and recognition of participation during graduation.

CPET community members can choose to complete either certificate program or both depending on their individual needs and interests. Furthermore, all community members can attend CPET events without joining a certificate program. By offering multiple ways to participate, CPET is able to meet the diverse needs of the community while also providing formal and institutional recognition for the teaching development work that participants undertake.

At MSU, GTA TLC offers two major types of events that support GSIs’ pedagogical development, namely hosting the bi-weekly Lunch and Learn seminars and facilitating GTA Preparation Program. The Lunch and Learn seminars serve as opportunities for GTAs to gather and focus on a specific pedagogical topic, including best practices for engaging students in large classes, inclusivity and culturally responsive teaching strategies, trauma-informed teaching, apprenticing GTAs into the academy through participation and identity construction, and professional development tools such as crafting diversity statements and electronic teaching portfolios. The MSU Graduate School recognizes the value of these seminars and considers them professional development toward the graduate and postdoc Certificate in College Teaching (CCT) program. Additionally, the GTA TLC collaborates and partners with faculty and academic staff from various units on the MSU campus as well as experts from outside the university in planning and executing professional development workshops.

While Lunch and Learn sessions occur frequently throughout the semester, about a dozen of our members also help organize the GTAP Program, a three-day-long orientation event occurring each August. The GTAP Program consists of workshops for new and returning GTAs across all departments and focuses on a broad range of topics relevant to educators at MSU. Ahead of the August sessions, we reflect on our lived experiences and working knowledge of evidence-based pedagogical practices to determine which policy training, resources, and support are needed most to help GSIs foster diverse, equitable, and accessible classes. Prior to the program, content is available via the learning management system. During the program, we present program content, moderate live workshops, and participate in panel discussions. By providing mentorship and training to new GSIs, our members build a greater sense of competence and professional identity as educators.

Another formal benefit we gain from participating in the GTA TLC is access to teaching resources. Due to our different disciplines of study, we know first-hand how different the pedagogical “GTA TLC has acted as a great resource to explore the art of teaching…It really helps you to see what the approach is when it’s transferring across content fields.”

– GS in Plant Biology, MSUnorms, technologies, and assessment methods can be department to department. As such, we expose community participants to various course design, content development, and evaluation assistance resources on- and off-campus. This helps members identify the aspects of courses ripe for redevelopment, lets GSIs know where to look for evidence-based practices, and allows GSIs to retain and pass on the knowledge shared during events.

The GTA TLC also helps prepare future GSIs by blending education theory, evidence-based best practices, and timely applications for practical training. As GSIs, we are still learning and growing in our abilities as educators. We benefit from frequent, repeated exposure to best practices, especially when we are simultaneously teaching. As nascent educators from various backgrounds, many of us are encountering challenges for the first time while others have already confronted the same issues. The GTA TLC community is well-equipped to understand the struggles many GSIs face and provide functional approaches to surmounting them. This is done by providing practical training, often on topics that can be applied immediately in the classroom.

For both CoPs presented here, formal benefits also include opportunities for student leaders to disseminate their best instructional practices at national conferences as well as regional and campus-specific teaching conferences. Otherwise, the formal benefits of the GTA“As [I constructed] my final teaching portfolio, I felt I had produced a body of work I was proud of and developed a valuable skillset!”

– GS in Chemical Engineering, Caltech TLC and CPET are parallel in structure but vastly different in size and scope. Many of the differences are explained by the comparative sizes of our institutions (Figure 1) and the breadth or specificity of the pedagogical needs of our communities. Regardless, the CoP framework is adaptable to widely different institutions and we urge the reader to reflect on how it may be implemented by recognizing how their own institution compares with each of ours. In addition, despite all the ways in which our institutional communities and CoP organizations are different, we have observed similar informal benefits, including creating community and cultivating growth, which we outline in the next section.

Sense of Community: Informal Benefits of our CoPs

Informal benefits are positive spillovers generated through producing the formal benefits and include safe spaces for GSIs, facilitating connections between educators, and fostering professional and personal growth. Taken together, the informal benefits generated within CPET and GTA TLC promote a sense of community, another defining feature of CoPs.

Space: Both our communities work to create a culture of care that responds to individual community needs. For CPET specifically, this manifests in collecting and responding to real-time feedback about the needs of Caltech community members. For example, during the transition to remote learning throughout the pandemic, CPET converted our discussion groups, seminars, and workshops to a virtual format. During this transition, the majority of event topics focused on remote“Although I have plenty of specific

takeaways from the [events] I

attended, my main outcome is

simply the recognition that I have a

tremendous amount left to learn.”

– GS in Geophysics, Caltech instruction and work-life-teaching balance, such as a workshop on how to break the ice in remote and Zoom classes and a discussion on teaching during difficult times based on trauma-informed teaching resources (Imad, 2020; McMurtrie, 2020). Similarly, the GTA TLC engages in active community empathy by promoting self-care and teaching with care. The GTA TLC contributes to self-care by providing a safe and empathetic space for GSIs to talk about challenges and seek support from peers in different fields. Educators also learn how to integrate the pedagogy of care into their undergraduate classrooms by respecting students’ lived experiences and recognizing mental health challenges of students through simulation tools, such as Kognito, which provide educators with language and tools to start conversations around mental health.

Both CoPs also serve as safe spaces for conversations on diversity, equity, and inclusion topics. CPET frequently hosts discussion groups about topics such as “Remote Learning and Equity” and “Inclusive Classrooms Beyond the Classroom: A CPET Discussion about Inclusive Field Courses.” CPET is also proactive by periodically revisiting issues using new resources or providing different perspectives. One of the most frequent topics discussed in the GTA TLC is the challenge of simultaneously teaching and troubleshooting in real-time.“Teaching online, asynchronously sometimes felt lonely and isolating, but by engaging with others a few times a month I felt like a community member, like my opinion and experience was valued, and like all my hard work was meaningful.”

– GS in Agricultural Resource and Food Economics, MSU In particular, many of us struggle with how to navigate unexpected challenges, like breakdowns in communication or disruptive outbursts, with grace and composure in front of our students. The GTA TLC focuses on a process of navigating difficult situations by acknowledging the severity of the situation, being aware of implicit biases, and educating oneself of the phenomena and the resources available to instructors and their students. All these dialogues and practices around community, intention, and kindness in turn translate to how instructors teach their students. As a result, these CoPs have become safe and brave spaces with therapeutic experiences where participants’ multilingual and multicultural assets are valued in an interdisciplinary setting and where empathy is shown and encouraged.

Connections: As members of our CoPs gather in the CPET and GTA TLC spaces, they form important connections on professional and personal levels, both within and outside the respective institutions. Events hosted by both our CoPs expose graduate instructors to informal networks of institutional peers from multiple academic levels (undergraduate students, graduate students, postdoctoral scholars, professors, and academic staff), allowing them to form professional relationships that can extend beyond pedagogical topics. CPET participants’ experiences are typically limited to small class sizes and STEM-focused fields, while speakers from institutions outside Caltech can draw from a breadth of pedagogical experiences, supplementing workshops and seminars given by the CTLO. Often, the approaches and theories shared by these visiting scholars serve as inspiration for novel ways to approach instruction or prove directly applicable to teaching at Caltech. In a similar vein, Lunch and Learn workshops provide opportunities for GTA TLC members to connect with practitioners at MSU and other schools. These interactions have provided members with in-class activities and assessment approaches that cut across disciplines. Even when a teaching tool is not immediately useful, GTA TLC participants gain familiarity and may find the tool useful in the future. Through this broad exposure, participants can understand and empathize with the universal parts of teaching while recognizing and appreciating the strengths of their unique teaching experiences.

Our CoPs also provide networking opportunities to help GSIs build social capital and establish professional connections that carry forward after graduate school. CPET works to make time and space for seminar speakers to network with GSIs. Workshop or seminar speakers, whether from on- or off-campus, often meet with participants after their talk. These follow-up events include CPET-organized lunches or happy hours where participants can further discuss workshop or seminar topics and receive more general support regarding pedagogy and career questions. Though GTA TLC has yet to sponsor in-person events, our workshops run notoriously long because it is so hard to stop the natural flow of conversation after Lunch and Learns. Usually, these interactions are followed by an open invitation to GSI participants from the speaker to connect with them in the future.

As CPET and GTA TLC members, we recognize the best in ourselves and each other. We communally support one another and share our experiences. Teaching can be really challenging, but we are often able to identify strengths in one another that we cannot readily recognize ourselves. One example of such an asset-based perspective is to encourage each other to apply for the teaching cohort fellowships, which provide funding and training to support scholarly work. GTA TLC members have recruited one another to apply for these fellowships, and helped each other construct and submit their successful applications. All these interpersonal connections are not limited to the CoP community. GTA TLC members are often tapped by leaders from different units across MSU to serve on student success steering committees and advisory boards; these interactions typically expand on discussions started during Lunch and Learn workshops.

Growth: CPET and GTA TLC community members often report finding it easier to conduct their research after learning pedagogical theories through CoP programming. Research shows teaching activities can improve graduate students’ research skills (Feldon et al., 2011), so it makes sense that GSIs engaged in our communities learn concepts and language that help them navigate and communicate in the world of research. For example, experimental design can be improved by looking through the lens of learning outcomes and backwards lesson design. Understanding expert amnesia helps to bridge the communication gap between students and advisors. The concept of a growth mindset gives students the ability to find comfort in not yet knowing information or concepts when interacting with their colleagues. As members of a CoP create new knowledge in their research, learning about how people learn and communicate can provide far-reaching, and often unintended, benefits.

In addition to growth as scholars, our members have reported increased confidence and self-awareness from networking and interacting at CoP events. For example, GTA TLC event participants sharedMy dual experiences as both a student with a disability and a TA are helpful when discussing accommodation and accessibility issues, but I have less experience with accessibility in terms of cultural issues, for which some international students in the GTA TLC have provided perspective.”

– GS in Human Development & Family Studies, MSU notes of gratitude with speakers and facilitators expressing how event topics helped them adopt evidence-based practices of teaching and learning. Through self-reflection, participants have also worked to become more inclusive and culturally responsive in their teaching and professional roles. With a shared understanding and appreciation of the challenges learners and instructors face, CoP educators from multiple disciplines continue to co-construct pedagogical knowledge and practices.

Members of both our CoPs benefit from connecting with others while serving as resources themselves (hooks, 1994) for fellow educators and GSIs. While both our CoPs have formal, expected outcomes, informal and unexpected spillovers from those formal elements have been critical in providing a community for graduate students in which they can grow and be supported as scholars and educators.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we share the two approaches our CoPs use to help graduate students develop as emerging scholar-educators in higher education. Though our two CoPs, CPET and the GTA TLC, operate on two campuses that are quite different in terms of size and research focus, it is clear that both groups generate and deliver formal and informal benefits to their participants. CoPs not only host events to introduce teaching resources to graduate students and discuss implementation through practical training, they also make room for graduate students to build scholarly, professional, and personal connections and to cultivate their own diverse teaching identities.

Strong graduate student agency and the institutional support from Caltech and MSU are the two driving forces underpinning the success of CPET and the GTA TLC. Graduate student members of both CoPs select, organize, and maintain pedagogical resources that are highly desired and best suited for their peers and themselves. For both CoPs, this work is done with support from faculty advisors and education specialists, including university centers of teaching and learning (CTL) and graduate studies offices. These institutional supports provide continuity for the CoPs. Moving forward, both CPET and the GTA TLC will continue our efforts with a special focus on teaching in the semi-post pandemic classroom while addressing topics related to fostering diverse and inclusive learning environments and trauma-informed pedagogical practices.

We encourage interested readers to investigate the extant resources at your institutions. There may be CoPs or closely aligned organizations operating at your college or university. These groups could serve as allies or partners for a graduate teaching CoP. If not, we encourage you to start a CoP at your school catered toward the specific teaching challenges, needs, and goals of your community. We presented our CoP experiences in this chapter to serve as examples of our most successful programs and resources, but your institution-specific needs and constraints may lead to you adopting alternative organizational structures, events, and foci. Significant differences exist in peer, institutional, and extra-institutional funding and support, but leveraging the energy and enthusiasm of GSI groups can help lead to successful CoPs.

We end by providing a brief list of low-barrier, actionable items to help you start the process of joining or starting a CoP at your institution. Are you ready to TEACH?

- Talk to colleagues: Organize an event to share the difficulties and challenges related to teaching at your specific institution.

- Explore available resources: Contact your university’s center for teaching and learning or related offices to discover existing opportunities for students to get involved. Connect with administrative and pedagogical experts available through the university.

- Apply for funding: Register as a student club or reach out to the CTL for support. The ability to provide refreshments at events, invite guest speakers, or purchase digital teaching tools is crucial to the long-term maintenance of the CoP.

- Collect community feedback: Send out a short survey (e.g., to the graduate student/postdoc listservs) to gauge general interest.

- Host focused discussions: Discuss a short article on any evidence-based pedagogy topic with other GSIs in your department. Some suggestions include effective grading strategies, active learning in recitations, and digital tools.

References

Brownell, S. E., & Tanner, K. D. (2012). Barriers to faculty pedagogical change: Lack of training, time, incentives, and… tensions with professional identity?. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 11(4), 339-346.

Caltech Registrar’s Office. (2021). Student Enrollment Data. https://registrar.caltech.edu/records/enrollment-statistics

Feldon, D. F., Peugh, J., Timmerman, B. E., Maher, M. A., Hurst, M., Strickland, D., Gilmore, J. A., & Stiegelmeyer, C. (2011). Graduate students’ teaching experiences improve their methodological research skills. Science (New York, N.Y.), 333(6045), 1037–1039. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1204109

Fong, C. J., Dillard, J. B., & Hatcher, M. (2019). Teaching self-efficacy of graduate student instructors: Exploring faculty motivation, perceptions of autonomy support, and undergraduate student engagement. International Journal of Educational Research, 98, 91-105.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York, NY: Routledge.

Imad, M. (2020, June 3). Leveraging the Neuroscience of Now. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/06/03/seven-recommendations-helping-students-thrive-times-trauma

Kolb, D. A. (2015). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (2nd ed.). Pearson FT Press PTG.

Lechuga, V.M. (2011). Faculty-graduate student mentoring relationships: Mentors’ perceived roles and responsibilities. High Educ, 62, 757–771.

McMurtrie, B. (2020, June 2). What Does Trauma-Informed Teaching Look Like? The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/teaching/2020-06-04

Mercieca, B. (2017). What is a community of practice? In J. McDonald & A. Cater-Steel (Eds.), Communities of Practice: Facilitating Social Learning in Higher Education (pp. 3-26). Singapore: Springer Nature.

Michigan State University Office of the Registrar (2021). Enrollment and Term End Reports. https://reg.msu.edu/roinfo/EnrTermEndRpts.aspx

Walton, G. M., Cohen, G. L., Cwir, D., & Spencer, S. J. (2012). Mere belonging: The power of social connections. Journal of personality and social psychology, 102(3), 513.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E. (2010) Communities of practice and social learning systems: The career of a concept. In Blackmore, C. (Editor), Social Learning Systems and communities of practice. Springer Verlag and the Open University.

Wenger, E. & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2017). Communities of practice go to university. In J. McDonald & A. Cater-Steel (Eds.), Communities of Practice: Facilitating Social Learning in Higher Education (pp. vii-x). Singapore: Springer Nature.

Acknowledgements: We would like to express our special gratitude to Dr. Stefanie Baier, the Graduate Student and Postdoctoral Instructional Development Director at the Graduate School at MSU and Dr. Jennifer E. Weaver, former Associate Director for University Teaching at the CTLO at Caltech, for their guidance, continuous encouragement, and intentional investment of time, energy and effort in helping us run our CoPs. Caltech authors would like to acknowledge that Caltech occupies the unceded, ancestral lands of the Gabrielino-Tongva people. MSU authors would also like to mention that MSU is a Land Grant University which occupies lands ceded in the 1819 Treaty of Saginaw, which was signed under duress. These lands are the ancestral, traditional, and contemporary lands of the Anishinaabeg — Three Fires Confederacy of Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples.