The Action Potential

Alivia Deimer and Jim Hutchins

Chapter under construction. This is the first draft. If you have questions, or want to help in the writing or editing process, please contact hutchins.jim@gmail.com.

What is an Action Potential?

An action potential, also known as a “spike” or termed a neuron “firing”, is a significant change in the membrane voltage of a neuron. The resting negative neuron, through a series of events covered later in this chapter, suddenly becomes positive, and this positive wave travels down its axon, causing firing to postsynaptic neurons.

The Three Phases of an Action Potential, Simplified

Depolarization

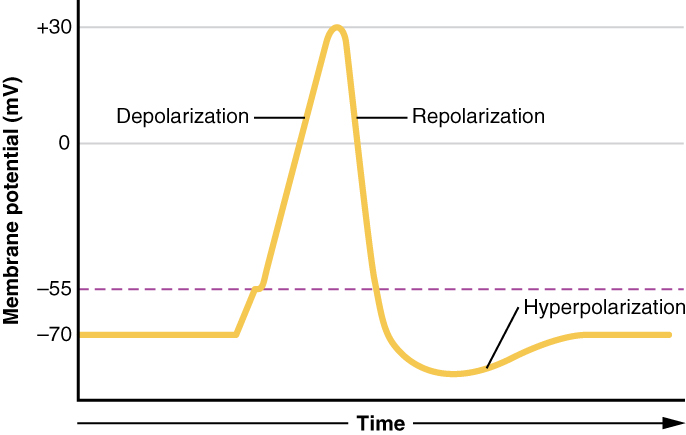

During depolarization, the negative charge of the membrane increases rapidly after the threshold voltage is reached (represented in this graph by the dotted purple line). The influx of positive sodium ions during this phase triggers the ongoing rising of the membrane charge, until it reaches the maximum positive potential.

Repolarization

After the highest voltage is reached, sodium channels begin to close, while potassium channels open. These potassium ions leave the cell, repolarizing the membrane by bringing it back down to the resting charge.

Hyperpolarization

Potassium leaving the cell and sodium channels being blocked cause the membrane to become more negative than the normal resting potential. This extreme negative charge means that an action potential is very unlikely to occur, even after sodium channels become unblocked. This phase is also often referred to as a neuron’s refractory period.

Mechanisms of the Action Potential

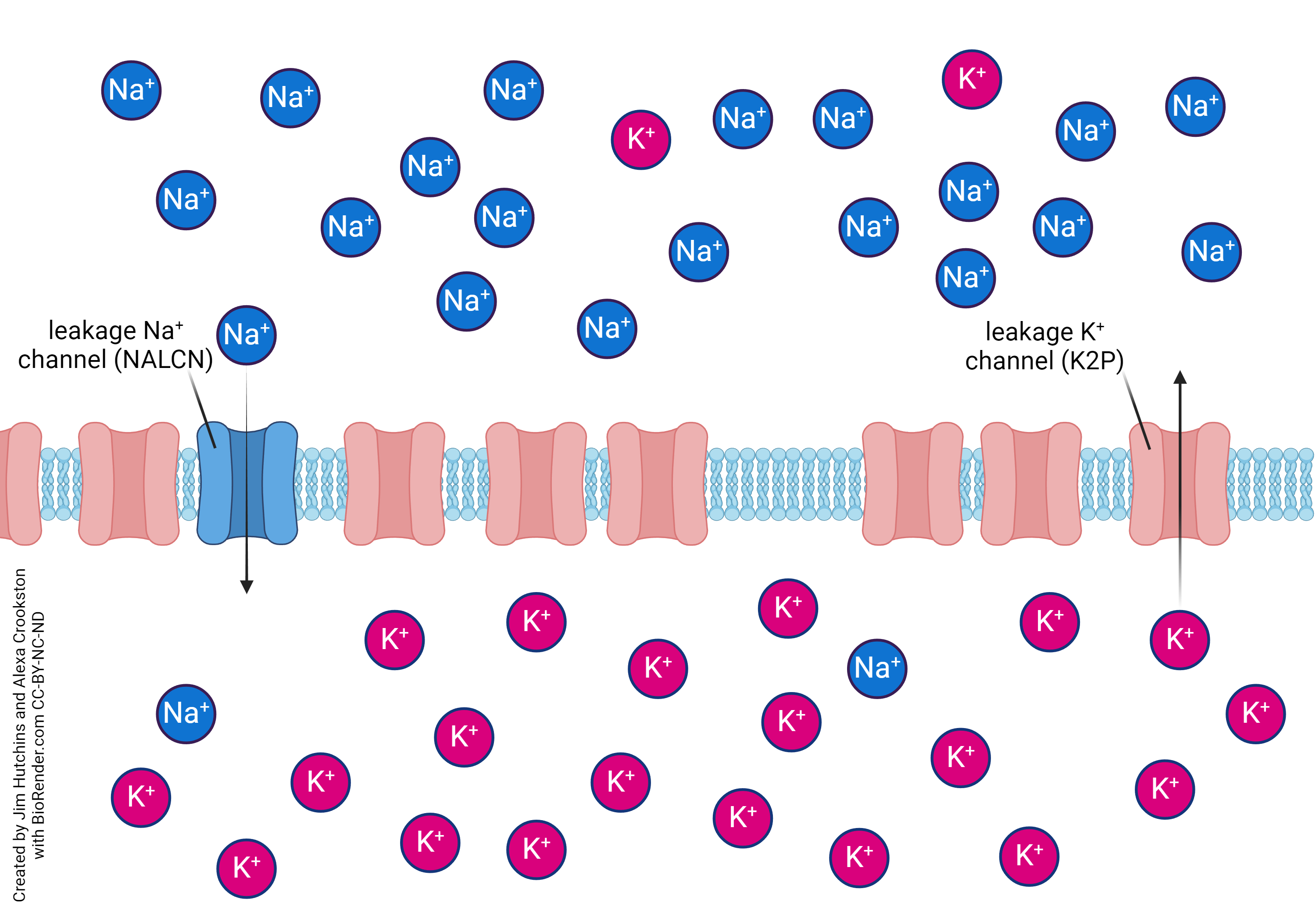

Before an action potential occurs, a neuron is at its resting potential. The commonly given voltage of a resting neuron is -70mV– this is not accurate for every neuron, but is an accurate enough average of neuronal charge to be widely used. The main ions involved in the mechanisms

of the action potential are sodium (Na+) ions and potassium (K+) ions. Both ions are present both inside and outside of the cell– however, their concentrations are quite different. While at rest, there are more Na+ ions outside of the cell, and more K+ ions inside the cell. To keep this resting potential steady, the cell membrane uses specialized gates called ion channels– these channels are specialized for one type of ion, and work to actively transport ions into and out of the cell. The ion channels for Na+ are mostly closed while a neuron is at rest, meaning that the wealth of positively charged Na+ ions cannot follow a concentration gradient to enter the cell. While a few Na+ ions can enter the cell, a special mechanism called the Sodium Potassium Pump keeps the neuron at rest by actively pumping Na+ ions out of the cell, bringing in 2 K+ ions to pump out 3 Na+ ions. This transport keeps the negative resting potential stable.

The closed Na+ channels create a tension in a resting cell membrane. The first reason for this tension is that Na+ ions are naturally drawn to move down a regular concentration gradient, from high concentration to low concentration. The ion channels preventing the Na+ from moving from the highly concentrated extracellular environment to the sparsely concentrated intracellular environment cause

constant pressure of Na+ ions trying to enter the cell. Along with this, there is significant electrostatic pressure as a result of the closed ion channels. The old saying of “opposites attract” is an apt description of this pressure– the positive Na+ ions are attracted to the negative interior of the cell, but cannot reach their destination. As a result of both of these processes, Na+ ions are set to flood the cell as soon as they have an opening.

This opening arrives when a cell receives an excitatory postsynaptic potential (ESPS). This signal causes the cell membrane to depolarize– meaning that its charge becomes more positive. Usually, it takes many ESPSs from a presynaptic cell to trigger this change in the cell membrane– as an ESPS hits the postsynaptic cell, it increases the charge by increments at a time, and this change in charge builds upon itself until the activation threshold is reached, and the action potential fires in an all-or-nothing response.

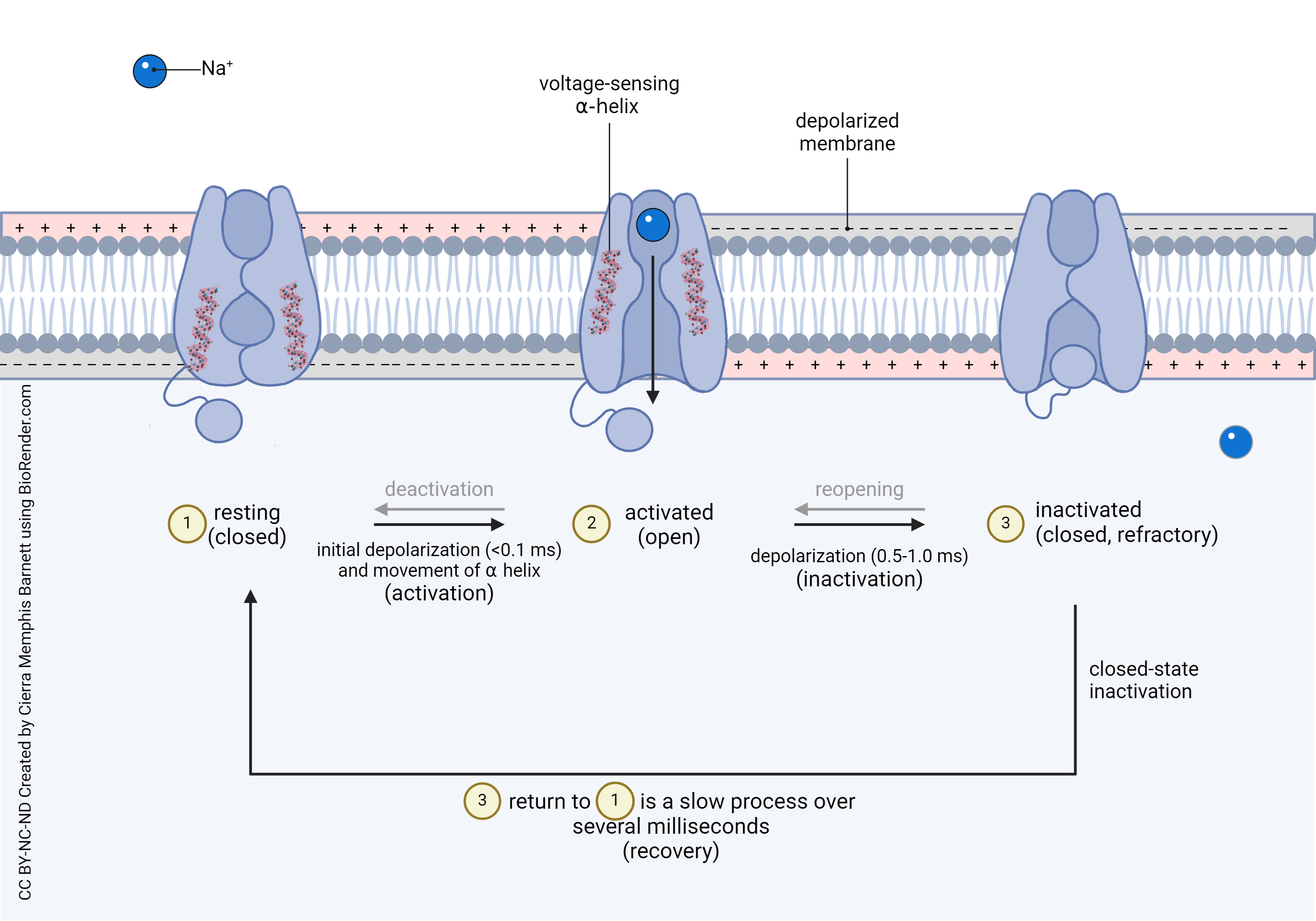

When the neuron reaches a certain charge– its activation threshold– then it opens its voltage gated Na+ ion channels. These channels– which were closed during the resting state– open in response to the change in voltage of the cell membrane. Specific charge-sensing proteins in these voltage gated channels react to the threshold voltage by pulling the Na+ channel open– this opening happens by the positive lysine and amino acids in the 4th alpha helix of the channel being repelled from the now-positive cell membrane. This opening allows a flood of Na+ ions to enter the cell. These ions then depolarize the membrane further, leading to more Na+ channels opening, leading to an extremely fast climb in charge– this whole process is known as the depolarization phase of an action potential.

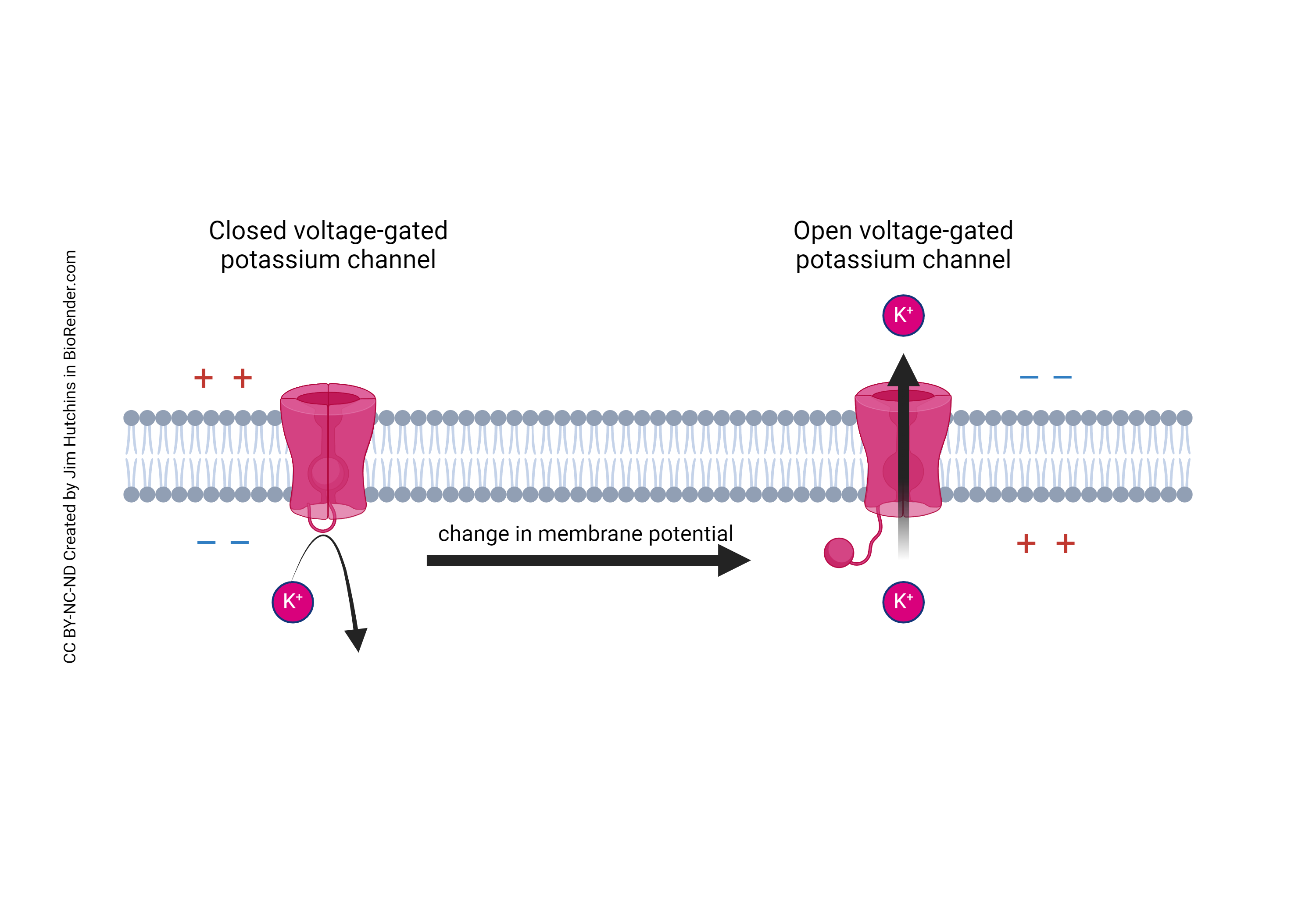

In response to this increase in intracellular charge, voltage gated K+ channels open. The intracellular environment is now more positive than the surrounding extracellular environment, and has a higher concentration of K+ ions than the extracellular environment. Because of this, the same tensions that were earlier attempting to draw Na+ into the cell are now pulling K+ out of the cell. This exiting of K+ begins to hyperpolarize the neuron, making it have a more negative charge– this process is called the hyperpolarization phase of the action potential.

After the flood of Na+ ions into the cell, the linkage protein between the 3rd and 4th domain of the channel binds into the “pore” or opening of the channel. This bound region acts as a dam against the flood of Na+ ions outside of the cell, preventing any more from entering. This action, combined with the flow of K+ ions out of the cell leading to a hyperpolarized membrane, causes a 1-2 millisecond break where the neuron returns to its resting state. During this refractory period, the blockage of Na+ channels means that an action potential cannot occur. Because of this refractory period, action potentials can only travel in one direction, and do not signal back down the axon after they fire– this one-way signal is the baseline for all neural firing in the brain.

Action Potentials as a Circuit

Action potentials are so powerful because they do not only occur in singular cells– as outlined before, the ESPSs generated by action potentials trigger other action potentials to occur in connected neurons. So goes the saying, “Neurons that fire together wire together.”

Neurons that often receive or transmit action potentials with each other often become accustomed to one another, making triggering an action potential in that circuit easier. This process is known as Long-term Potentiation (LTP). This interesting process is outlined in the short video below.