Voltage-Gated Channels

Tess Johnson; Avalon Marker; Caleb Bevan; Jackson T. Anderson; Shelby Pickett; and Jim Hutchins

Chapter under construction. This is the first draft. If you have questions, or want to help in the writing or editing process, please contact hutchins.jim@gmail.com.

Voltage Gated Channels

Outline:

- Na+

- K+

- Ca2+ = Transmitter release.

- Found on the presynaptic axon terminal

- Voltage-gated calcium channels (CaVs) are transmembrane proteins activated by depolarization of membrane potential. The calcium that enters through CaVs is crucial for cellular processes including gene expression, hormone release, neurotransmitter release, cardiac muscle contraction, and pacemaker activity.

- Based on their activation threshold, CaVs are classified as either high or low voltage activated (HVA and LVA).

- Genes that encode for voltage-gated calcium channels are grouped into three subfamilies, each with their own distinct function:

- The CaV1 subfamily conducts L-type Ca currents

- CACNA1S, CACNA1C, CACNA1D, and CACNA1F

- The CaV2 subfamily conducts N-, P/Q-, and R-type Ca currents

- CACNA1A, CACNA1B, and CACNA1E

- The CaV3 subfamily conducts T-type Ca currents

- CACNA1G, CACNA1H, and CACNA1I

- The CaV1 subfamily conducts L-type Ca currents

- L, N, T type currents

- L-type Ca currents (High-threshold calcium current ICa(L)) initiate excitation-extraction coupling in muscle cells and secretion in endocrine cells, control gene transcription, as well as controlling many enzymes.

- N-, P/Q-, and R-type Ca currents (ICa(P), ICa(Q), ICa(N), ICa(R)) and the associated CaV2 subfamily are often found concentrated in nerve terminals where Ca influx is required for the release of chemical neurotransmitters; P/Q- and R-types currents are poorly understood.

- T-type Ca currents (ICa(T)) are activated at negative membrane potentials and are transient; these are modulated by muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. These particular channels are important as they are seen in cells that repetitively fire, such as sinoatrial nodal cells that serve as pacemakers in the heart or neurons in the thalamus that generate sleep rhythms.

- Synaptic transmission is triggered by opening of mainly N- and P/Q-type calcium channels

- Pore is formed by the α1 subunit

- This is similar to the voltage-gated Na+ channel α subunit

- α2 and δ subunits are associated glycoproteins

- β subunits are intracellular

Chapter:

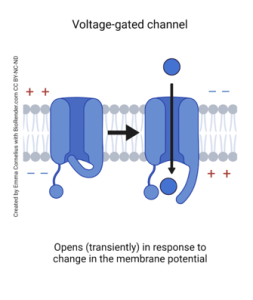

Ion channels allow molecules to flow in and out of cell membranes. These channels are activated and deactivated in different ways, such as by substance. Voltage-gated ion channels open and close in response to a cell’s membrane potential.

Voltage-gated ion channels are along the membrane of a neuron, specifically the axon, and are made of transmembrane proteins. Each ion is made of three structures: the voltage sensor, the pore, and the gates. The voltage sensor tracks when there are changes in the neuronal membrane. The pore is the channel in which ions flow, and the gates are what open or close in response to the changing membrane to allow ions into the neuron.

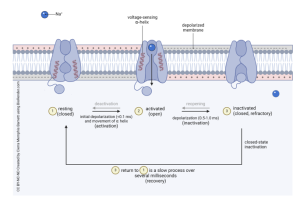

Voltage-gated ion channels exist in three forms:

- The resting state of the neuron has closed channels

- The active state of the neuron has open channels

- The refractory period of the neuron has inactivated closed channels

When a neuron becomes active, the change in potential causes the voltage-gated ion channels along the neuron’s axon to open. The four main molecules that can pass through these channels are sodium, potassium, calcium, and chloride. These ions will fluctuate based on the function of the neuron (i.e., firing an action potential).

Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels

Voltage-gated sodium ion channels are essential for the activation of a cell, specifically for an action potential to fire. Voltage-gated ion channels stay in a resting state when not being used. The channels are closed, and ions cannot pass through during this state. When a positively charged sodium ion interacts with the channel outside the cell membrane, the voltage-sensing α-helix area tells the channel gate to open. The channel becomes activated, and the gate opens, which allows sodium ions to enter the cell. This causes depolarization of the membrane. Once the sodium ion is no longer detected, the channel will be inactivated, and the channel gate will close. This happens during the refractory period. The cell will then go into a recovery period, which is when the channel transitions from an inactivated state back to a resting state.

Voltage-Gated Potassium Channels

Voltage-gated potassium ion channels work similarly to sodium ion channels but during different stages of an action potential firing. When a neuron becomes depolarized, voltage-gated potassium channels sense this, causing the channel gate on the inside of the cell to open. Potassium ions are allowed to flow out of the cell in response. Once potassium leaves the cell, this causes hyperpolarization, which brings the cell back to its resting state. The channel gate will then close in response to hyperpolarization, not allowing potassium ions to exit the cell.

Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels

Voltage-gated calcium ion channels are activated in response to the depolarization of the cell. The channel gate then opens, allowing calcium ions to enter the cell. Calcium in the cell is important for the release of neurotransmitters and gene expression. When the cell hyperpolarizes, the voltage-gated calcium ion channels sense this, and the channel gate closes. This prevents more calcium ions from entering the cell.

Voltage-Gated Chloride Channels

Voltage-gated chloride ion channels are activated in response to hyperpolarization of the cell. The channel gate will open, allowing chloride ions to enter the cell. These assist in creating more hyperpolarization of the cell, maintaining cell volume, and setting the resting membrane potential. Once a cell is at its resting membrane potential, these channel gates close, preventing more chloride ions from entering the cell.

Media Attributions

- Voltage gated channel © Emma Cornelius is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Voltage Gated Sodium Channel Internal Gate Mechanisms Membrane Charges © Cierra Memphis Barnett is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Voltage gated potassium channel © Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license