Neurotransmitters: γ-Amino Butyric Acid (GABA)

Alivia Deimer and Jim Hutchins

Chapter under construction. This is the first draft. If you have questions, or want to help in the writing or editing process, please contact hutchins.jim@gmail.com.

The role of GABA

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the Central Nervous System (CNS). This means that GABA works to decrease firing in the CNS– it primarily acts upon neurons in the brainstem, thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and basal ganglia.

GABA production and transport

The GABA Shunt

The GABA shunt is an extremely important mechanism that produces and holds GABA. This process utilizes a product of the Krebs cycle called

alpha-ketoglutarate. Alpha-ketoglutarate is produced by GABA alpha-ketoglutarate transaminase (also known as GABA-T). As the name suggests, GABA-T transaminases alpha-ketoglutarate– this means that GABA-T exchanges an amino group with alpha-ketoglutarate, converting it into a glutamate called L-glutamic acid.

Once this L-glutamic acid is produced, an enzyme called Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase (GAD) catalyzes the decarboxylation of L-glutamic acid. Basically, this enzyme takes the carboxyl group away from L-glutamic acid and puts a hydrogen atom in its place. This decarboxylation changes L-glutamic acid into GABA. The decarboxylation of L-glutamic acid by GAD is the rate limiting step in the synthesis of GABA.

Transporting GABA

After GABA is produced, it is then actively transported into synaptic vesicles by a protein called the Vesicular Inhibitory Amino Acid Transporter (VIAAT). How VIAAT transports GABA into these vesicles is not yet known. Once inside these vesicles, GABA can be released into a cell’s synapse, where it can bind to receptors in the postsynaptic cell.

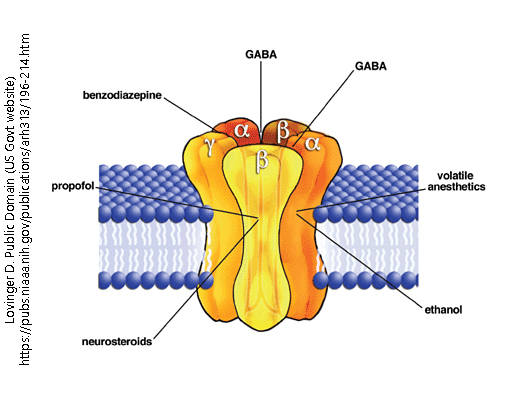

The GABA-A Receptor

The GABA-A receptor is ionotropic, meaning that it is a gated ion channel. This receptor is a pentamer, meaning that it is made of five subunits (as seen in the diagram below). The GABA-A receptor is a chloride channel that opens when GABA (or a GABA agonist) binds to it– this binding results in a conformational change, clearing the way for chloride to enter. This opening of chloride channels makes the cell more negative, which is functionally how GABA acts as an inhibitory agent.

This receptor has two alpha helix groups, two beta strand groups, and one gamma group. The common arrangement of these groups is as follows:

Beta-2 → Alpha-1 → Beta-2 → Alpha-1 → Gamma-2

The structure of this receptor has many diverse binding sites, allowing for many drugs to act using the GABA-A receptor. Some of these drugs include benzodiazepines, ethanol, propofol, anesthetics, and neurosteroids. While GABA binds between the beta and alpha groups, benzodiazepines bind between the gamma and alpha groups– this is just one example of how the structure of this receptor allows for diverse binding.

Ionotropic GABA receptor

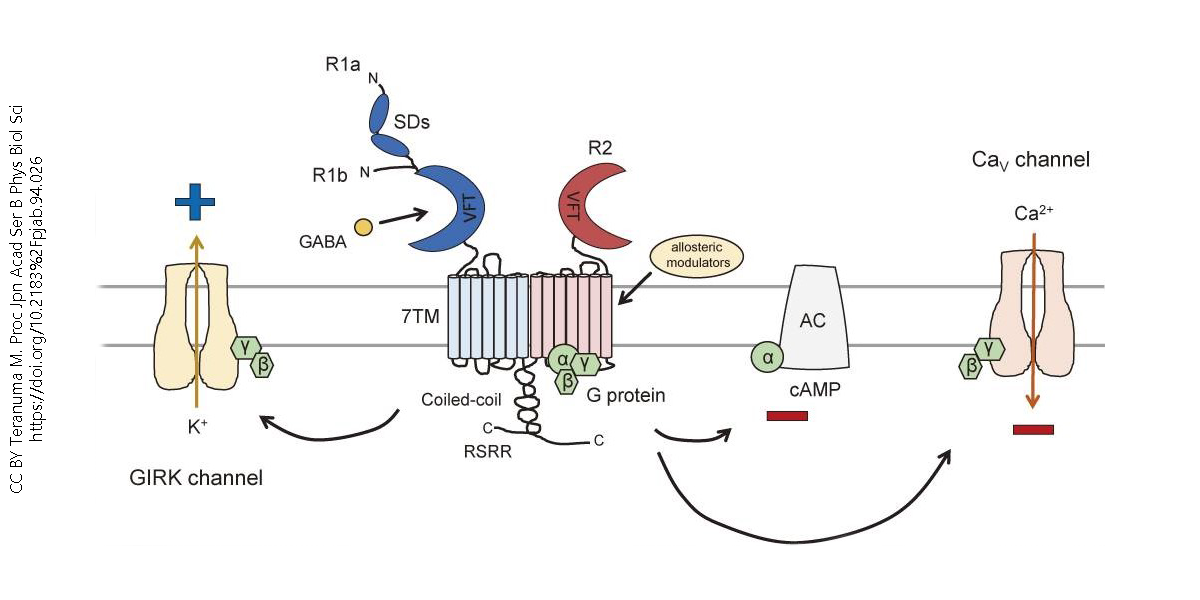

The GABA-B Receptor

The GABA-B receptor is G-Protein coupled. These receptors are slower acting than their GABA-A receptor counterpart, but can have larger inhibitory effects, like decreasing calcium conductance in the cell which reduces the total amount of neurotransmitters released, for example.

GABA-B receptors are known as heterodimers, which means that they have two different protein subunits that bind together to do a job. One of these units (R1) binds to GABA, while the other one (R2) works with the G-Protein. The R1 subunit has something called the Venus flytrap domain (VFT) which contains the GABA binding site. Connected also to this subunit are the heptahelical transmembrane domain (7TM) and C-terminal intracellular tail. The R2 subunit couples with the G protein using its own VFT. The R2 subunit also allows for allosteric modulators to bind– these modulators can change the R1 group’s affinity for GABA. The R1 and R2 subunits then interact at the coiled-coil protein domain.

Once GABA binds to the R1 subunit, the R2 subunit activates Gαi/o proteins. These proteins then lower cAMP activity by inhibiting adenylyl cyclase, and inhibit calcium channels. Both of these result in neuronal inhibition.

GABA Reuptake and Metabolism

Excess GABA is absorbed back into either the presynaptic cell or surrounding glial cells by GABA plasma membrane transporters (GATs). The GABA absorbed back into nerve terminals can be held and re-used by the cell– however, GABA absorbed into glial cells is metabolized (or, broken down) instead of being held. GABA-T, the same enzyme that converts alpha-ketoglutarate into L-glutamic acid, metabolizes GABA into succinic semialdehyde. Succinic semialdehyde cannot directly be formed into GABA, so it instead enters the Krebs cycle, where it is made into glutamine. This glutamine is transferred to neurons via Sodium-neutral amino acid transporters (SNAT), which open the door for neutral amino acids to cross the cell membrane. Once inside the neuron, glutamine can then be decarboxylated into GABA. This process shows the cyclical nature of GABA production, where metabolized GABA is used to synthesize more GABA.