Neurotransmitter Receptors

Garrett Nelson and Jim Hutchins

Chapter under construction. This is the first draft. If you have questions, or want to help in the writing or editing process, please contact hutchins.jim@gmail.com.

What Are Neurotransmitter Receptors?

Neurotransmitter receptors are specialized protein molecules embedded in the membranes of neurons. These receptors act as gatekeepers, interpreting chemical signals in the synaptic cleft and translating them into cellular responses. They play a crucial role in synaptic transmission, influencing everything from muscle contraction to cognitive processes like learning and memory.

Types of Neurotransmitter Receptors

Neurotransmitter receptors are broadly categorized into two main classes: ionotropic receptors and metabotropic receptors.

Neurotransmitter receptors are broadly categorized into two main classes: ionotropic receptors and metabotropic receptors.

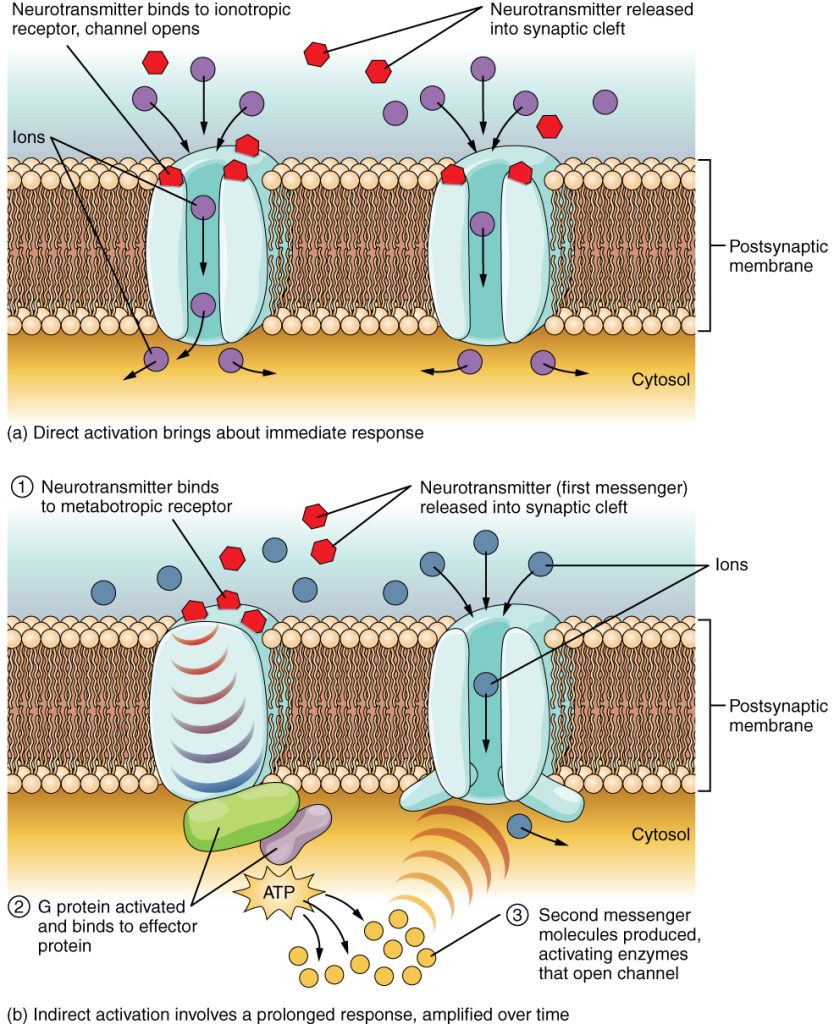

Ionotropic receptors, also known as ligand-gated ion channels, directly control ion channels. When a neurotransmitter binds to an ionotropic receptor, the pore of the receptor opens, allowing specific ions to flow through. This immediate ion fluctuation rapidly changes the cell’s membrane potential.

Metabotropic receptors, or G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), operate through more complex signaling pathways. When a neurotransmitter binds to a metabotropic receptor, it activates an associated G-protein composed of alpha, beta, and gamma subunits. The G-protein can then influence secondary messengers, leading to a range of intracellular responses. These effects are generally slower but longer-lasting than those of ionotropic receptors.

Ionotropic and Metabotropic receptors will be explored in more depth in the chapter Comparing Ionotropic and Metabotropic Receptors

How Do Neurotransmitter Receptors Work?

The function of neurotransmitter receptors begins with the release of neurotransmitters from the presynaptic neuron. This release is typically triggered by an action potential – an electrical impulse that travels down the axon to the synaptic terminal. When the action potential reaches the terminal, voltage-gated calcium (Ca²⁺) channels open, allowing Ca²⁺ to enter the cell. The influx of calcium ions prompts synaptic vesicles, containing neurotransmitter molecules, to fuse with the presynaptic membrane and release their contents into the synaptic cleft through exocytosis.

Once in the synaptic cleft, neurotransmitters diffuse across the small gap and bind to specific receptors on the postsynaptic neuron. In the case of ionotropic receptors, neurotransmitter binding leads to an immediate and direct effect. Ion channels open, permitting the flow of ions like Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, or Cl⁻, which quickly alter the membrane potential. These rapid changes can result in excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) if depolarization occurs or inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) if hyperpolarization occurs.

For metabotropic receptors, the process is a bit more intricate. When a neurotransmitter binds, the receptor activates its associated G-protein, causing the alpha subunit to exchange GDP for GTP and dissociate from the beta and gamma subunits. These subunits can then influence various effectors, such as ion channels or enzymes that produce second messengers like cAMP. Second messengers amplify the signal within the cell, triggering large shifts in brain activity that can alter gene expression, protein synthesis, or synaptic plasticity.

After neurotransmission, the neurotransmitters must be cleared from the synaptic cleft to prevent excessive signaling. This can be achieved through reuptake by transporter proteins, enzymatic degradation, or simple diffusion away from the synaptic site.

Receptor Dynamics and Regulation

Neurotransmitter receptors are not static. Their numbers and sensitivity can change based on neural activity and environmental factors. Receptor desensitization, a process in which repeated stimulation of a receptor by its ligand leads to a decrease in its responsiveness, can occur when continuous exposure to a neurotransmitter diminishes the receptor’s responsiveness.

Alternatively, receptor upregulation occurs when receptor numbers increase due to prolonged neurotransmitter scarcity, enhancing its sensitivity.

The interplay between these dynamics plays a role in tolerance and sensitivity to certain drugs, where long-term use or long-term scarcity alters receptor expression and interaction.

Clinical and Therapeutic Relevance

Neurotransmitter receptors are essential for synaptic plasticity, which underlies learning and memory. By influencing synaptic strength through processes like long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD), these receptors are fundamental to neural circuit configuration. Dysfunctional receptors can be linked to various neurological disorders, such as schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, and epilepsy.

Pharmacological agents often target specific receptors to help restore this balance. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) enhance serotonin signaling for treating disorders like depression, while antipsychotics act on dopamine receptors to help manage disorders like schizophrenia.