The Second Step: Access – Searching the Literature

In this chapter, we will jump into accessing the evidence/searching for literature to help answer your clinical question. A treasure hunt for evidence!

Content includes:

- Introduction to Literature Searching

- Steps of a Literature Search

- Using Critical Appraisal Tools

- Peer-Reviewed Sources

- Types of Evidence Sources

- Level of Evidence

- Database Selection and Search Tools

- Search Strategies and Techniques

- Evaluating the Quality of Evidence

- Systematic and Scoping Reviews

- Applying Literature Searches to Clinical Practice

Objectives:

- Describe the purpose and importance of literature searching in evidence-based nursing practice.

- Explain the steps of a literature search.

- Explain what constitutes a peer-reviewed source.

- Differentiate between various types of evidence sources and their roles in research.

- Identify key databases and search tools relevant to nursing and healthcare research.

- Identify the level of evidence on a table of hierarchy.

- Demonstrate effective search techniques, including Boolean operators, MeSH terms, and keyword searches.

- Evaluate the credibility, reliability, and relevance of research articles and sources.

- Explain the significance of systematic and scoping reviews in EBP.

- Apply search findings to inform clinical decision-making and enhance nursing practice.

Key Terms:

Boolean Operators: Words such as AND, OR, NOT used in search queries to refine and narrow (or broaden) literature searches.

Database: A structured collection of research articles and other resources that allow users to search for relevant literature (e.g., PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library).

Grey Literature: Research and information not published in peer-reviewed journals, including government reports, conference proceedings, and white papers.

MeSH (Medical Subject Headings): A controlled vocabulary used in databases like PubMed to standardize search terms and improve search accuracy.

Peer-Reviewed Journal: A scholarly publication in which articles undergo rigorous evaluation by experts in the field before publication to ensure credibility and quality.

Primary Source: Original research articles or studies conducted by the authors themselves, providing firsthand data and findings.

Relevance Ranking: The algorithm-based process used by search engines and databases to prioritize and display search results based on their significance to the query.

Secondary Source: A source that synthesizes, summarizes, or reviews primary research, such as systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and literature reviews.

Systematic Review: A rigorous and structured review of research studies that critically appraises and synthesizes evidence on a specific topic.

Scoping Review: A type of review that maps the available literature on a broad topic to identify key concepts, gaps, and research trends.

Search Strategy: A structured approach to finding literature using specific keywords, Boolean operators, truncation, and database filters.

Tertiary Source: Reference materials such as textbooks, clinical guidelines, or encyclopedias that summarize information from primary and secondary sources.

Truncation: A search technique using a symbol (e.g., *) to retrieve variations of a word (e.g., nurs* for nurse, nurses, nursing).

Introduction

The next step in our EBP journey is to “Access” the literature (AKA: search for evidence in published literature). Searching for evidence in the literature, often referred to as a literature review, is a fundamental step in the evidence-based practice (EBP) process. Nurses and healthcare professionals rely on high-quality research to make informed clinical decisions, improve patient outcomes, and contribute to advancing nursing knowledge. However, navigating the vast amount of available literature can be challenging. This chapter gives nursing students essential skills for conducting systematic and efficient literature searches. It explores various sources of evidence, introduces key research databases, and teaches search strategies that enhance the retrieval of relevant information. Additionally, it discusses how to critically evaluate research, manage citations, and apply findings to real-world clinical practice. By mastering these skills, nursing students will be better prepared to integrate research into patient care and support the continuous improvement of healthcare practices.

Duncun and Holtsander (2012) outlined that the skills associated with retrieving information are of paramount importance to healthcare professionals. The literature review is, per the National Library of Medicine’s (2021) MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) database, “published materials providing an examination of recent or current literature. It also … covers a wide range of subject matter at various levels of completeness and comprehensiveness based on analyses of literature that may include research findings.” Each literature review must include the concepts and ideas based on the research or clinical question. The PICO(T) approach helps to define and translate the terms and concepts to be used for the literature seach:

P – Population

I – Intervention

C – Comparison

O – Outcome

T – Time

The primary goal of a literature review is to explore what is already known and identify gaps in knowledge regarding an unresolved issue in practice. Additionally, it serves to determine how research evidence can inform the resolution and management of the issue. By synthesizing existing studies, the literature review establishes the background and context necessary for conducting research (Polit & Beck, 2017). A literature review serves as a critical foundation for research by examining existing knowledge and highlighting gaps in understanding related to an unresolved issue in practice. It not only identifies what has been studied but also uncovers areas that require further investigation. Additionally, a literature review helps determine how research evidence can guide the resolution and management of the issue (McGrath & Brandon, 2014). By synthesizing findings from various studies, it provides the necessary background and context for conducting meaningful research and advancing evidence-based practice.

Introduction to Literature Searching

Nurses must stay updated on the latest research to provide the best care possible. A well-structured literature search follows a systematic approach to ensure that the most relevant and credible evidence is retrieved. It is a bit like playing detective. Finding articles often entails trial and error at first, and then a systematic approach to get the information that we are trying to find. Figuring out the right databases, keywords and phrases, Boolean operators, and limiters is a bit like putting pieces of a huge puzzle together. It is important to get all of the pieces figured out in order to find the most appropriate literature for our research or clinical question.

Finding out how all of the puzzle pieces fit together is the first step in our literature search. However, we must also be cognizant of the “why” behind a good literature search. The following table highlights key reasons why literature searching is essential in nursing practice:

Table: Literature Searching in Nursing Practice

| Reason | Description |

| Supports EBP | Ensure nursing care is informed by the latest, high-quality evidence. |

| Enhances Clinical Decision-Making | Helps nurses make well-informed choices that improve patient outcomes. |

| Identifies Best Practices | Allows nurses to compare interventions and. choose the most effective ones. |

| Prevents Outdated Practices | Helps phase out ineffective or harmful interventions. |

| Aids in Professional Development | Encourages lifelong learning and keeps nurses current in their field. |

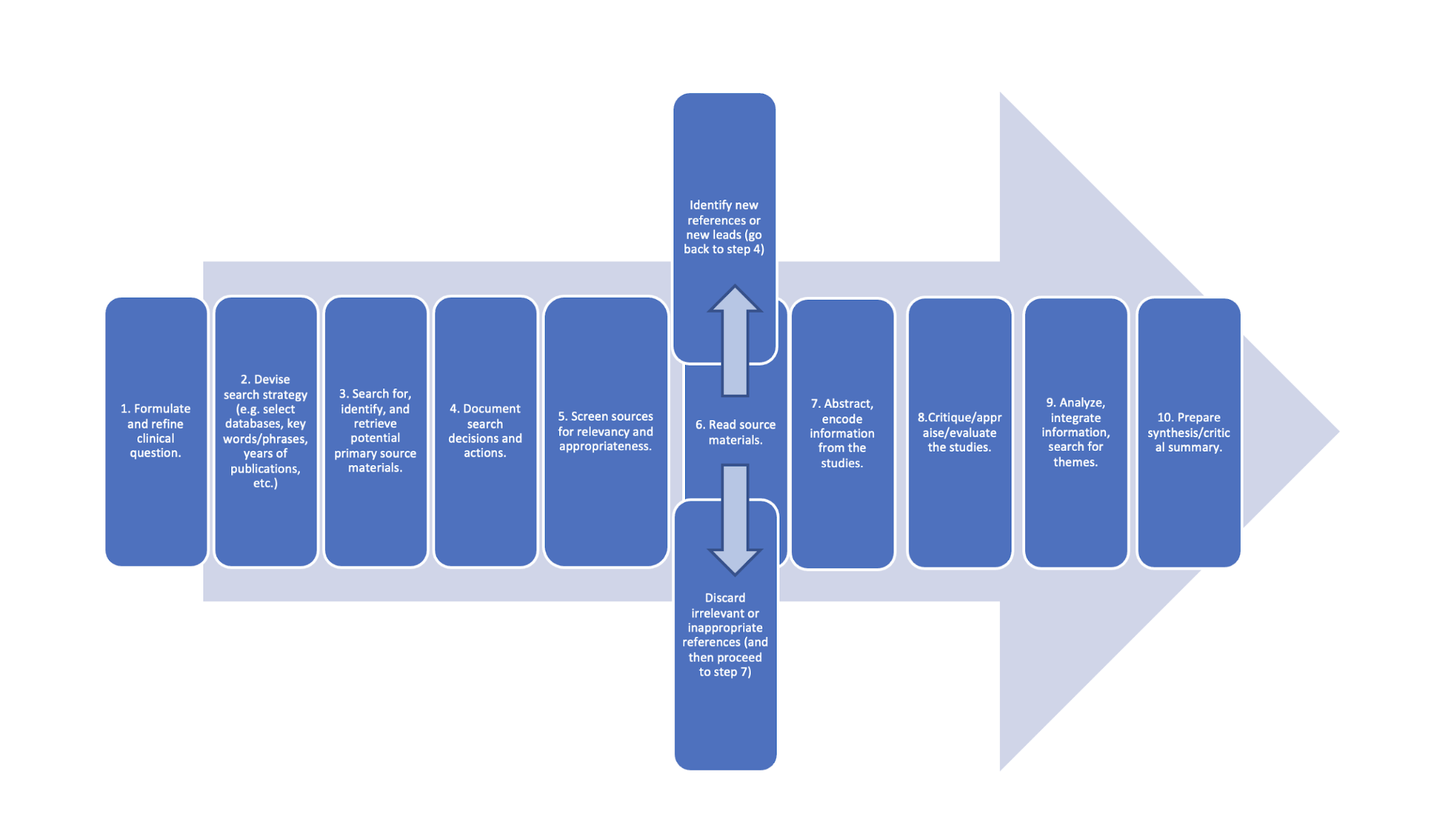

Steps of a Literature Search

A structured and systematic literature search is the foundation of evidence-based practice (EBP) in nursing. Each step in the process ensures that research findings are relevant, credible, and applicable to clinical decision-making. By following a stepwise approach, nursing students and professionals can efficiently navigate vast amounts of literature, extract high-quality evidence, and synthesize findings to improve patient care.

The steps in performing a literature search include:

1. Formulate and refine clinical question.

The first and most crucial step in conducting a literature search is defining the research question. A well-structured question guides the search strategy and determines the type of evidence needed. The PICO framework (Patient/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) is commonly used to develop focused clinical questions. A poorly defined question leads to inefficient searches and irrelevant results, making this step vital in the research process.

2. Devise search strategy (e.g., select databases, key words/phrases, years of publications, etc.).

Once the research question is established, a clear search strategy is necessary. This includes selecting appropriate databases (e.g., PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library), identifying keywords and MeSH terms to capture all relevant literature, and applying filters such as date range, study type, and population to refine search results.

3. Search for, identify, and retrieve potential primary source materials.

After defining a search strategy, the next step is to conduct the search across multiple databases. Researchers should focus on peer-reviewed primary sources, such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort and case-control studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

Databases like PubMed and Cochrane provide access to high-quality evidence, ensuring reliable and credible results.

4. Document search decisions and actions.

Tracking search decisions maintains transparency and reproducibility in the literature review process. Researchers should record the databases searched and search terms used, filters applied (e.g., date restrictions, language, study type), and number of results retrieved from each search. Documenting these actions prevents duplicate efforts and helps refine future searches.

5. Screen sources for relevancy, appropriateness.

Not all retrieved studies will be relevant to the research question. At this stage, researchers need to review article titles and abstracts to determine alignment with the research focus, apply inclusion and exclusion criteria to filter out studies that do not meet research needs, and prioritize high-quality, peer-reviewed sources over non-peer-reviewed or opinion-based articles. Effective screening prevents time wasted on irrelevant studies and ensures a focused literature review.

6. Read source materials.

Discard irrelevant or inappropriate references (and then proceed to step 7) or identify new references or new leads (go back to step 4). This iterative process ensures completeness and prevents important evidence from being overlooked.

7. Abstract, encode information from the studies.

Once the final set of sources is determined, researchers extract key data from each study. This step involves: Summarizing study objectives, methods, and findings, noting key statistics, conclusions, and limitations; and, organizing findings into categories or themes.

8. Critique/appraise/evaluate the studies.

Not all research is of equal quality. At this stage, researchers critically evaluate the credibility and validity of each study. This involves assessing study design and methodology, identifying potential biases and conflicts of interest, using critical appraisal tools (e.g., CASP, JBI, GRADE) to systematically evaluate research quality. This ensures that only high-quality evidence contributes to the final literature synthesis.

9. Analyze, integrate information, search for themes.

With the evaluated studies in hand, researchers analyze and integrate findings, looking for patterns, consistencies, and gaps. This step includes comparing results across studies to determine generalizability, identifying themes (e.g., common benefits or limitations of an intervention), and recognizing gaps in the literature that require further research. A strong analysis strengthens the final interpretation of evidence.

10. Prepare synthesis/critical summary.

The final step is to synthesize the findings into a cohesive narrative. This synthesis serves as the foundation for:

- Research papers and systematic reviews.

- Clinical guidelines and recommendations.

- Evidence-based practice changes in healthcare settings.

The critical summary should clearly: Summarize key findings and trends, highlight strengths and limitations of studies, discuss implications for nursing practice.

Figure Above: Steps of a Literature Search

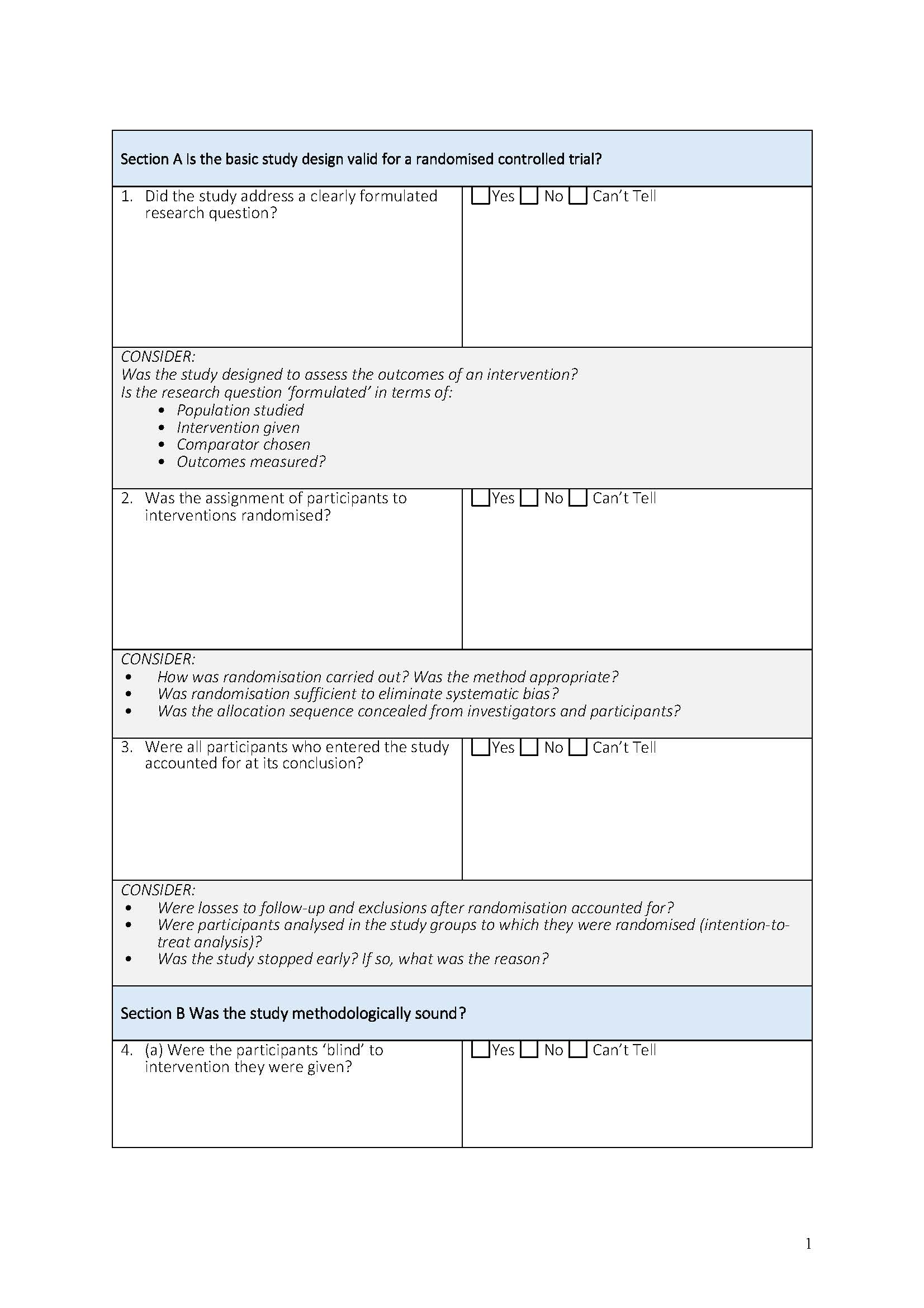

Using Critical Appraisal Tools in Evaluating Research Evidence

Evaluating research quality is a fundamental step in evidence-based practice (EBP). To ensure that findings are reliable, valid, and applicable, healthcare professionals use critical appraisal tools to systematically assess the strengths and limitations of research studies. These tools provide structured frameworks for analyzing study design, methodology, bias, and overall credibility.

Several well-established critical appraisal tools are widely used in nursing and healthcare research, including CASP, JBI, and GRADE. Understanding how to use these tools effectively helps nursing students and professionals distinguish high-quality evidence from weaker studies, ultimately supporting informed clinical decision-making.

Each critical appraisal tool has a specific focus, depending on the type of research being evaluated. The table below provides an overview of some of the most widely used tools in nursing and healthcare research.

Table: Critical Appraisal Tools

| Critical Appraisal Tool | Type of Research Evaluated |

| CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) | Evaluates qualitative studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case-control studies, systematic reviews, and economic evaluations. Provides structured checklists to assess methodological rigor and applicability. |

| JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools) | Used for qualitative and quantitative research, including systematic reviews, RCTs, cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, diagnostic studies, and prevalence/incidence studies. Focuses on validity, reliability, and relevance. |

| GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) | Primarily assesses the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in systematic reviews and guidelines. Grades evidence from high to very low based on study design, risk of bias, consistency, directness, and precision. |

| PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) | Evaluates systematic reviews and meta-analyses, ensuring transparent and complete reporting of study selection, data synthesis, and bias assessment. |

| Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool | Specifically designed for randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Evaluates bias related to randomization, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. |

| Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) | Used for cohort and case-control studies, assessing selection, comparability, and outcome/exposure to determine study quality. |

| MMAT (Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool) | Evaluates qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies by assessing study design, data collection, and integration of methods. |

Using critical appraisal tools follows a systematic approach that involves reviewing specific study components. Below are key areas commonly assessed in research studies:

1. Assessing Study Validity and Reliability

✔ Are the study objectives clearly stated?

✔ Is the research design appropriate for the question being asked?

✔ Are the methods used to collect data clearly described and reproducible?

2. Evaluating Risk of Bias

🔍 Was the sample size adequate and representative of the population?

🔍 Were participants randomly assigned (in RCTs)?

🔍 Were the researchers blinded to avoid bias?

🔍 Were funding sources and conflicts of interest disclosed?

3. Analyzing Results and Clinical Relevance

📊 Are the findings statistically significant and clinically meaningful?

📊 Do the conclusions align with the study results?

📊 Can the findings be applied to real-world clinical practice?

Using a structured checklist, such as those provided by CASP or JBI (See EBP Project Module in Canvas for these checklists), ensures that each of these factors is thoroughly evaluated before applying the research to patient care.

Example: Using CASP to Evaluate a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT)

Consider a study evaluating whether nurse-led smoking cessation interventions improve long-term smoking abstinence rates compared to standard physician-led interventions.

Using the CASP RCT Checklist, the appraisal process would involve answering the following:

1️. Did the trial clearly define its research question and intervention?

2️. Were participants randomly assigned to treatment and control groups?

3️. Was blinding used to minimize bias?

4️. Were follow-up periods sufficient to assess long-term outcomes?

5️. Are the results statistically significant and clinically applicable?

Page 1 of the CASP tool:

Peer-Reviewed Sources

An evidence/literature search is a very organized search in which keywords and phrases are used to find peer-reviewed sources on a specific topic and/or to answer a clinical question. A well-thought-out search will reveal articles that are current, reliable, valid, accurate, and pertinent.

Evidence-based practice should be based on the best evidence that comes from peer-reviewed articles. A peer-reviewed source means that the content has been reviewed by an expert in that field before it is published. The peer review process is blinded, which means the article author does not know who is reviewing their work and vice versa. When an article is submitted to a journal for publication, the journal will send the de-identified manuscript (to remove the author’s name) to expert peer reviewers (usually multiple reviewers). The potential article is reviewed, edits and revisions are suggested (if applicable) and sent back to the author, the author makes the revisions, and only then the article is published. Sometimes, submissions are rejected entirely if the content does not match the goal of the journal or if the article is deemed to have lack of rigor, validity, or accuracy. This laborious process results in a well-written and accurate source of information.

Peer-reviewed articles include the author’s title and credentials, a reference page, research data, and research analysis as a minimum. Peer-reviewed sources are considered to be of a higher quality, although the consumer/reader should still critically appraise when reading the published content.

Types of Literature Sources

There are three main types of sources that are found in a literature review: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary.

Primary sources:

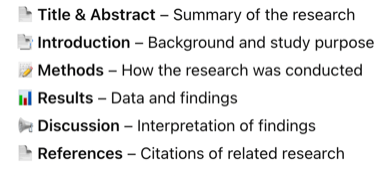

Primary sources are articles that are written by the researcher that actually performed the study. The structure of a primary research article usually includes a Title and Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and References.

A primary source presents original research conducted by the authors themselves. These sources provide firsthand data and findings, making them essential for building new knowledge in nursing and healthcare. The characteristics of a primary source include original research with direct data collection, it is written by the researchers who conducted the study, and it includes the methodology, results, and conclusions. Types of primary sources include clinical trials, experimental studies, cohort or case-control studies, qualitative research, and original survey or questionnaire data.

We will be focusing mostly on primary sources for our EBP Projects.

The structure of a primary research article usually includes the following:

![]() Knowledge to application link.

Knowledge to application link.

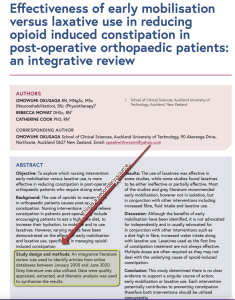

Here is an example of a primary study/source.

Secondary sources:

Secondary sources are descriptions of someone else’s study. They are pre-appraised evidence. They are not written by the researcher that performed the study. Literature reviews, therefore, are secondary sources. The EBP poster that you are creating is indeed considered a “secondary source”, because you did not conduct the research that you are summarizing.

Types of secondary sources in research include:

- Systematic Reviews: These merge and synthesize findings from various studies.

- Meta-Analyses: A technique for integrating multiple research findings statistically.

- Metasyntheses: Less about reducing information from multiple (qualitative) studies and more about interpreting it.

It is important to note that systematic reviews are essential in EBP. They are rich in information that multiple experts have reviewed. Considered to be the top database for systematic reviews is the Cochrane Library (contains systematic reviews, clinical answers, and is a central registry of controlled trials). This portal allows users to search several databases containing evidence-based medical resources: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, Health Technology Assessments, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Another top database is the Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence-Based Practice Database (evidence summaries, systematic reviews, recommended practices, and best practice information sheets). These are wealthy in information to begin your evidence search. See what articles they reviewed, as those are most likely primary sources and perfect for your EBP project.

Tertiary Sources:

A tertiary source is a condensed summary of knowledge from primary and secondary sources. These sources are typically used for quick reference rather than original research. Characteristics of tertiary sources include a summary or general knowledge; it does not include original resources or analysis and is often used for background information. Examples of tertiary sources include textbooks, encyclopedias, clinical handbooks, and government reports or summaries.

![]() Knowledge to application link.

Knowledge to application link.

Here is an example of a secondary source. Now, this one could be tricky. Even though it says “An Integrative Review” in the title, the abstract states “this study…” in the conclusion, which could trick the unknowing eye.

Table Below: Types of Sources

| Source Type | Definition | Examples |

| Primary Sources | Original research conducted by the authors, presenting firsthand data. | Clinical trials, cohort studies, qualitative studies. |

| Secondary Sources | Summaries or analyses of multiple primary research studies. | Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, literature reviews. |

| Tertiary Sources | Summarized information drawn from primary and secondary sources. | Textbooks, clinical guidelines, reference handbooks. |

Table Below: Comparison of Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources

| Feature | Primary sources | Secondary Sources | Tertiary Sources |

| Definition | Original research with firsthand data. | Summarizes, analyzes, or reviews multiple primary sources. | Condense summaries for quick reference. |

| Includes New Data? | Yes | No | No |

| Examples | Clinical trials, cohort studies, qualitative research. | Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, literature reviews. | Textbooks, clinical handbooks, encyclopedias. |

| Strength in EBP | Essential for building new knowledge. | Helps interpret and summarize research. | Useful for background knowledge but not for clinical research. |

Research versus practice/theory and informational articles:

For any evidence-based practice, and especially for your EBP project for this course, it is imperative to use actual research articles. As you are beginning to seek evidence to help answer your clinical question, there needs to be a focus on determining which type of article you are reading. Utilizing a non-research article can result in an invalidated review of evidence, as it would not be evidence but instead just anecdotal information or opinion. While the information contained in non-research articles may provide a breadth of information, they do not have utility in a review of evidence because they do not address the central question: “What is the current state of evidence on this research problem?” (Polit & Beck, 2021).

Here are some guidelines to look for when determining a research article from non-research:

A research study must:

- Ask a research question (or allude to the question)

- Identify a research population or sample

- Describe a research methodology

- Test or measure something

- Summarize the results

Examples of article types that are not research studies:

- Literature reviews (these are reviews of multiple, independent studies)

- Meta-analyses (these are analyses of multiple, independent study findings)

- Editorials

- Case studies

- Comments or letters relating to previously published studies

- General informative articles without a research methodology or research question

![]() Hot tip! Never judge an article by its title. For example, “Myocardial Infarctions in Athletes, and Underlying Etiologies” sounds “scholarly” and convincing that it is research-like, yes? Ah, but it’s not. This was an article that came from a running magazine but was found in a scholarly database. Conversely, “Exposure to Sunlight and the Happiness Factor” sounds like a general, informative, non-scholarly, non-research article. However, this is indeed a peer-reviewed, primary source, scholarly, quantitative experimental research article. It can be tricky!

Hot tip! Never judge an article by its title. For example, “Myocardial Infarctions in Athletes, and Underlying Etiologies” sounds “scholarly” and convincing that it is research-like, yes? Ah, but it’s not. This was an article that came from a running magazine but was found in a scholarly database. Conversely, “Exposure to Sunlight and the Happiness Factor” sounds like a general, informative, non-scholarly, non-research article. However, this is indeed a peer-reviewed, primary source, scholarly, quantitative experimental research article. It can be tricky!

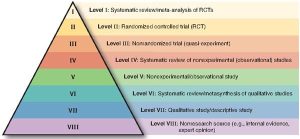

Levels of Evidence

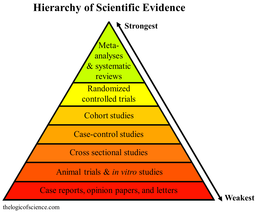

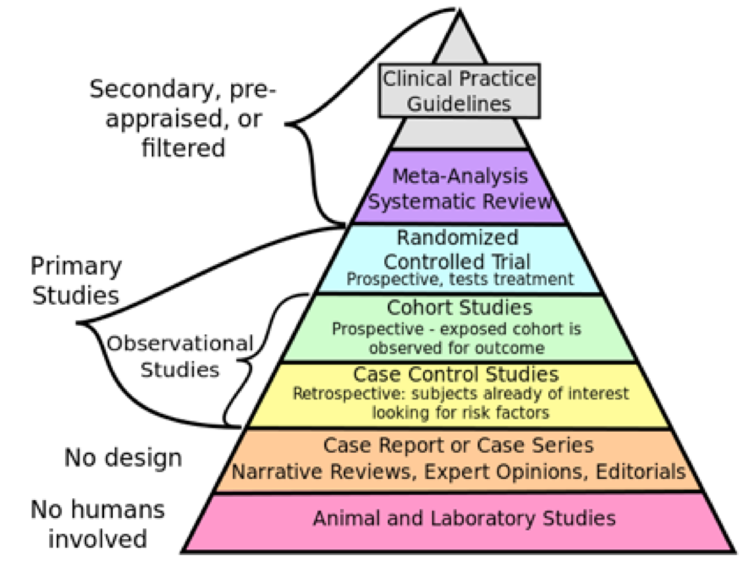

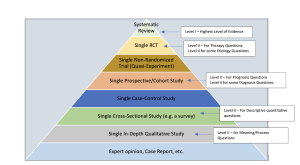

In evidence-based practice (EBP), not all research is created equal. Some types of evidence are considered stronger and more reliable than others. The levels of evidence hierarchy help researchers and clinicians determine the strength of the research findings they use to guide clinical decision-making. Understanding these levels ensures that nursing students and healthcare professionals can critically evaluate studies and select the most robust evidence to answer research questions effectively. Often, these levels are depicted in a table or pyramid.

The higher up the table or pyramid, the more rigorous a source is and the less bias it is likely to have. However, the choice of evidence level depends on the research question being asked. Different types of research designs are suited for different types of questions in healthcare. For example, if the research question is about a patient’s experience undergoing cardiac catheterization for a qualitative study, the most appropriate level of evidence would be Level VI on this chart. This would be the most rigorous level for this type of question. If we are asking a clinical question related to an intervention and are curious about a particular cause-and-effect outcome, perhaps a randomized controlled trial (RCT) would be the most appropriate study type to answer our question. Therefore, the levels do not indicate “better” for the sake of a study, but simply provide a guide for which to base appropriate searches for the most rigorous literature depending on the clinical question being asked.

Most EBP and research textbooks talk about the “evidence hierarchy” as it relates to bias and strength of rigor. There is some debate as to if “rigor” and “best evidence” is synonymous. The answer? No. Rigor and “best evidence” do not go hand-in-hand. If I could, I would remove the phrase “evidence hierarchy” and change it to “category of evidence”.

Here is why. When textbooks talk about the evidence hierarchy, they are referring to the potential for bias behind the study, with little regard to the actual clinical question the study was asking.

Let’s back up and think about this.

At the pinnacle (top) of most evidence hierarchy diagrams is the systematic review. Systematic reviews are a careful synthesis of multiple primary studies related to each other by using strategies that reduce biases and random errors. At the bottom of the diagram are expert opinions and case reports. When the hierarchy model was made, it reflected the Cochrane Collaboration’s initial focus on evidence as it related to the effectiveness of therapies rather than about broader health care questions (Polit & Beck, 2021). Indeed, as we look near the top of the diagram, we can see that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are a high level of evidence. RCTs are well suited for medical therapies (think double-blinded pharmaceutical trials).

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are often hailed as “the gold standard” for quantitative research studies in health care because they allow the researcher to control the experiment and isolate the effect of an intervention by comparing it to a control group. This minimizes bias. However, the inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation can be quite strict and the high level of control is not consistent with real-world conditions, which can reduce the generalizability of findings to the population of interest (Applied Statistics in Healthcare Research).

However, if we look at the strength of evidence as it relates to medical therapies, we are placing the evidence from non-RCT and qualitative research “lower”. Let’s think about this. If our clinical question is qualitative in nature and we are trying to find out about the lived meaning of, for example, living with cancer, our highest level of evidence would not need to be at the top of the pyramid as it would not be applicable to have an RCT to measure a lived experience.

Here’s another diagram with various levels of evidence:

This is a summary of yet another hierarchy:

|

Level |

Description |

|

Level 1 |

Evidence obtained from systematic review of relevant and multiple RCTs and meta-analyses of RCTs |

|

Level 2 |

Evidence obtained from at least one well-designed RCT |

|

Level 3 |

Evidence obtained from well-designed, non-randomized controlled trials, single group pre-post cohort, time series, or matched experimental studies |

|

Level 4 |

Evidence obtained from well-designed non-experimental research |

|

Level 5 |

Opinion of respected authorities based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees |

Thankfully, nurses spoke up and resisted a standardized hierarchy of evidence for EBP. You will now find various diagrams showing the rank of evidence as it pertains to the clinical question. Level 1 remains systematic reviews, but level II includes some categories that would be amenable to focused clinical questions related to descriptive questions and meaning questions.

Here is a modified evidence hierarchy for various types of EBP questions:

Finally, this diagram developed by Polit and Beck (2021) seems to be the easiest, simplest, and most descript. This next diagram is what should be used for your Synthesis of Evidence Worksheet.

With all of this said, what are your best evidence sources for your EBP project? Well, it depends! But, mostly, you will not need to worry about finding Level I studies as we will be focusing on just primary sources. You will be using Level II, III, and Level V articles for your therapy/intervention questions.

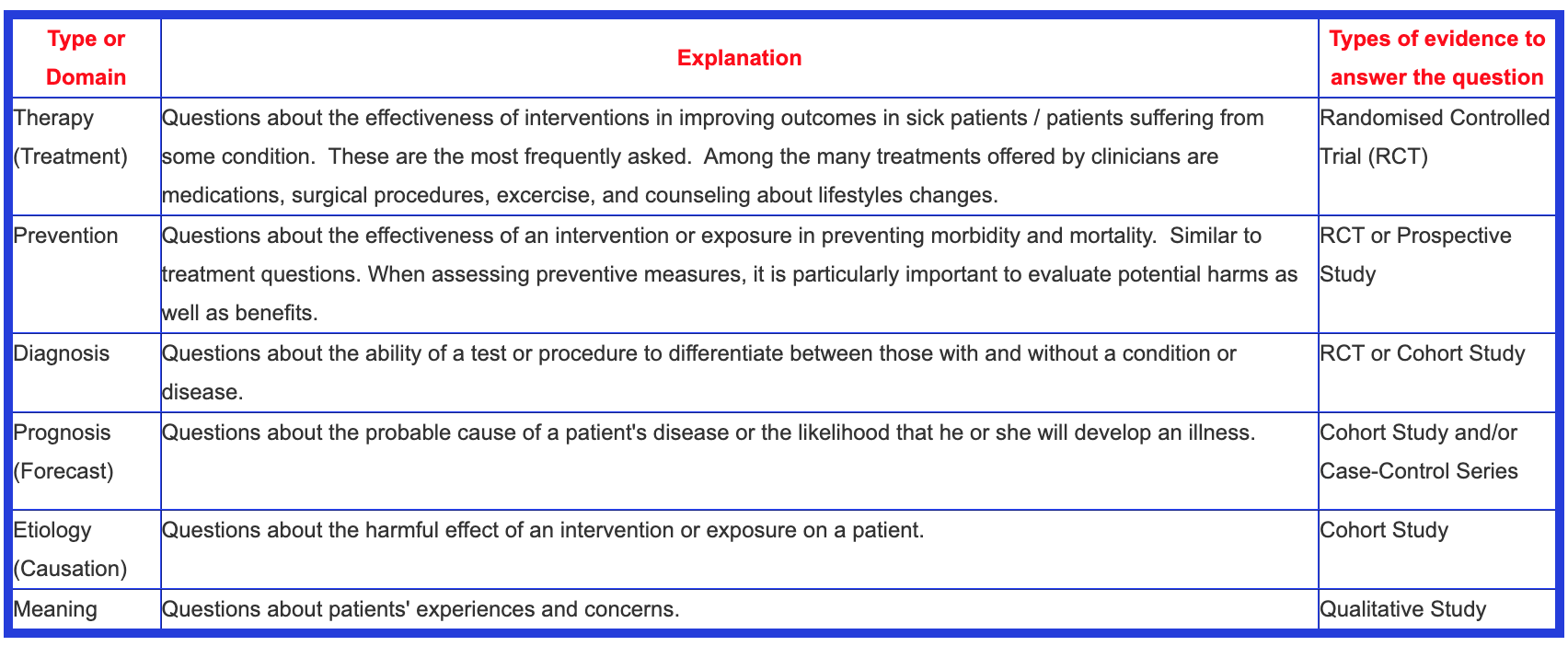

Here is a helpful table that differentiates the appropriate research methodologies for various research questions.

Let’s watch a helpful video about evidence hierarchies: Understanding Levels of Evidence – What are Levels of Evidence?

BCPhysio. (2012). Understanding ‘levels of evidence’ – what are levels of evidence?

. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5H8w68sr0u8

Database Selection and Search Tools for Finding Evidence

Database Selection

Conducting an effective literature search requires access to reliable databases and search tools that provide high-quality, peer-reviewed research. Nursing and healthcare professionals must be proficient in selecting the appropriate databases to find the most relevant and credible evidence. The choice of database depends on the research question, as different platforms specialize in various types of studies, clinical guidelines, and systematic reviews. Understanding the scope, strengths, and limitations of each database ensures a more efficient and comprehensive search process.

Choosing the Right Database for Nursing Research

Healthcare research databases vary in coverage, accessibility, and content focus. Some databases are dedicated to nursing and allied health literature, while others provide broader medical research. Each of these databases serves a unique function, and researchers often use multiple platforms to ensure a comprehensive search. For example, a nurse investigating patient experiences with chronic pain management may prioritize CINAHL and PsycINFO for qualitative studies, while a clinician evaluating medication efficacy would rely on PubMed and EMBASE for randomized controlled trials. Cochrane Library is emphasized for its systematic reviews, making it essential for high-level EBP. Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Database is included as a top-tier resource for nursing-focused evidence synthesis and best practice implementation. These databases collectively provide comprehensive access to nursing and healthcare research, ensuring that students and professionals can retrieve the most relevant and credible evidence.

The table below outlines key databases commonly used in nursing research, along with their primary features.

Table: Databases

| Database | Scope and Specialization | Best Used For |

| CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) | Nursing and allied health literature including journal articles, dissertations, and conference proceedings. | Finding nursing-specific research, qualitative studies, and clinical practice guidelines. |

| PubMed | Biomedical and life sciences literature, including MEDLINE and NIH-funded research. | Broad searches for clinical trials, systematic reviews, and medical research. |

| Cochrane Library | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on healthcare interventions. | Identifying high-quality evidence for EBP and clinical decision-making. |

| Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Database | Evidence-based nursing and healthcare research, including systematic reviews and best practice recommendations. | Locating high-quality nursing practice guidelines, systematic reviews, and implementation science research. |

| PsycINFO | Psychology and behavioral sciences research. | Exploring mental health topics and psychological aspects of nursing care. |

| Google Scholar | Wide-ranging academic content, including journal articles, theses, and grey literature. | Broad searches, but requires very critical evaluation due to varied source credibility. A good place to start a search, but should be used warily as sources are not vetted for peer-review or quality. |

Understanding Search Tools & Strategies for Finding Evidence

Effective literature searching goes beyond entering a few keywords into a database. Search tools and strategies help refine results to retrieve the most relevant and high-quality studies. Boolean operators, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), filters, truncation, and citation tracking are essential techniques that improve the precision of a search.

Scholarly databases are updated frequently to hold the latest evidence, and these are the best choices for finding relevant evidence to answer compelling research/clinical questions. For an EBP venture, one of the best places to begin finding evidence are systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines, or meta-analyses. Why? Well, preprocessed evidence is often appraised by an entire team, which means that the research conclusions are usually cross-checked, fairly objective, and accurate. This takes some guesswork out of finding the best evidence. However, be sure it is current. Is it within the last few years? If so, chances are good that you are on the right track.

However, for our EBP project, as it is a rapid literature review, we need to stick with primary articles. You may indeed look at secondary articles as a starting point, as they offer great overviews and have rich and valuable bibliographies (take a look at the primary articles that they are reviewing).

Novices to searching through databases for evidence are encouraged to contact the healthcare librarian who may be able to assist you with finding the most appropriate databases, search terms, and search phrases, and help to refine your search.

Literature Searches in Databases:

The first step in finding literature is to determine which databases you will search within. There are many options to choose from. Bibliographic databases are available to you from within the university library through EBSCO host.

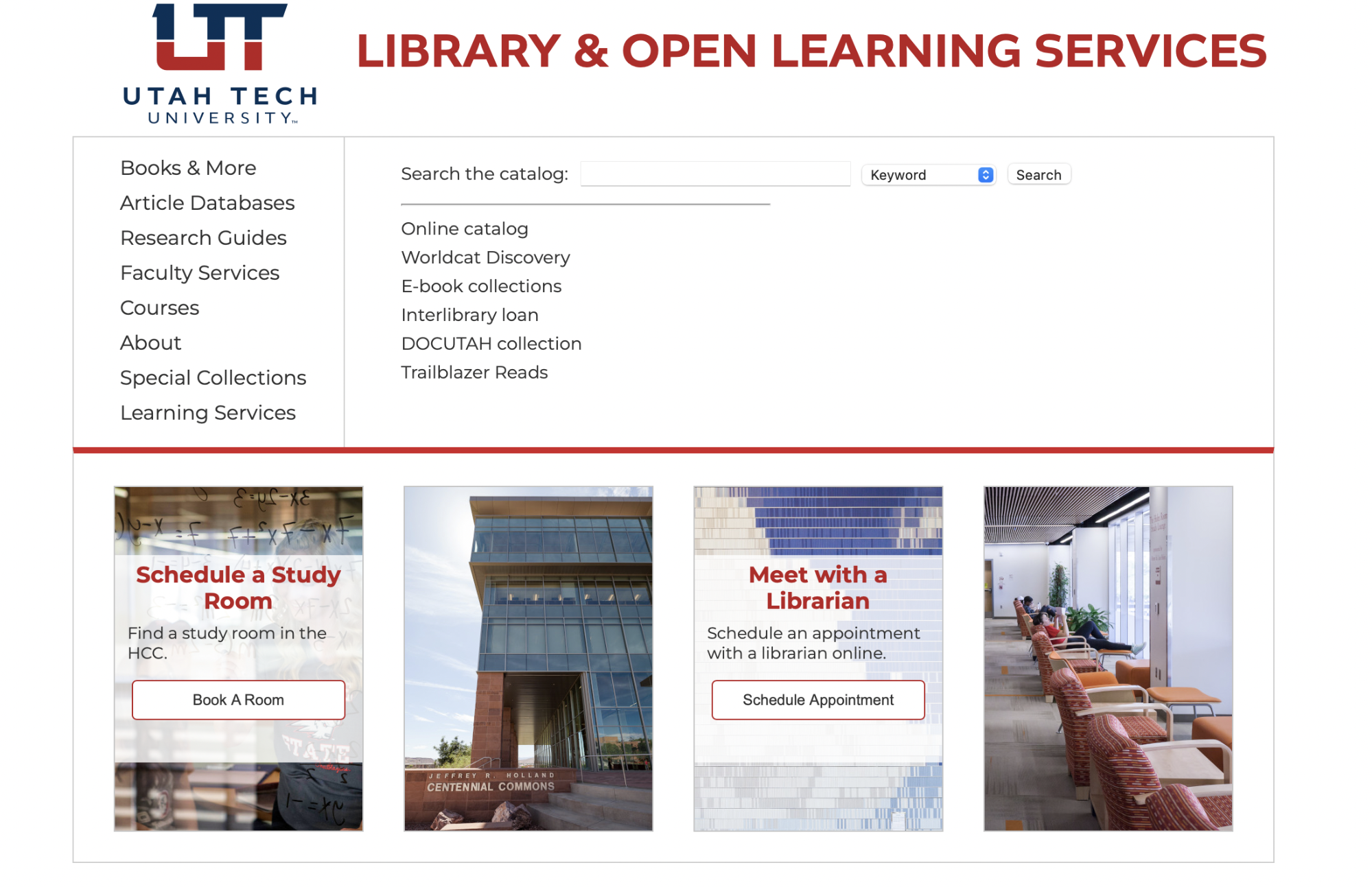

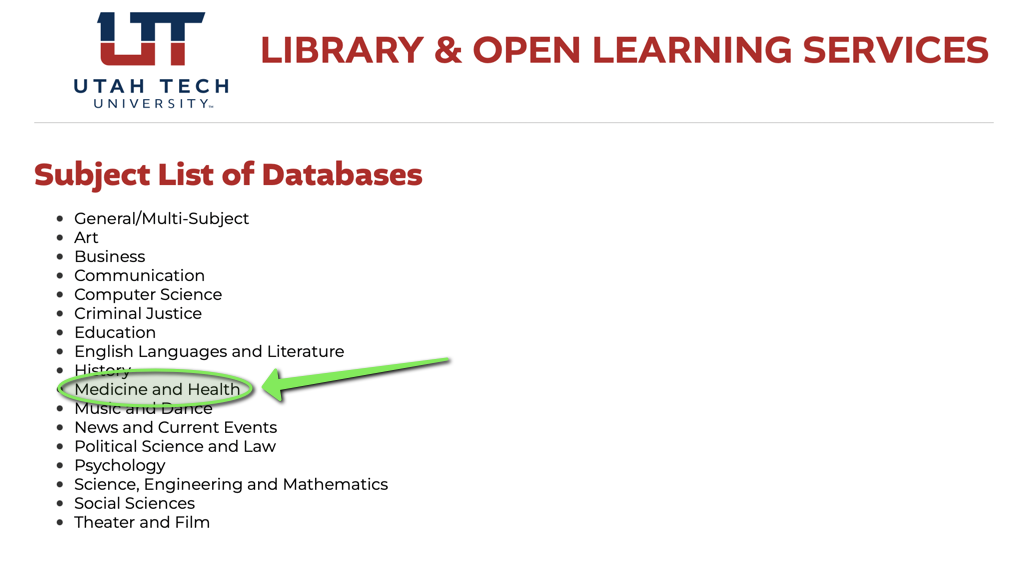

First, navigate to the university library: library.utahtech.edu

Second, click on “Article Databases”:

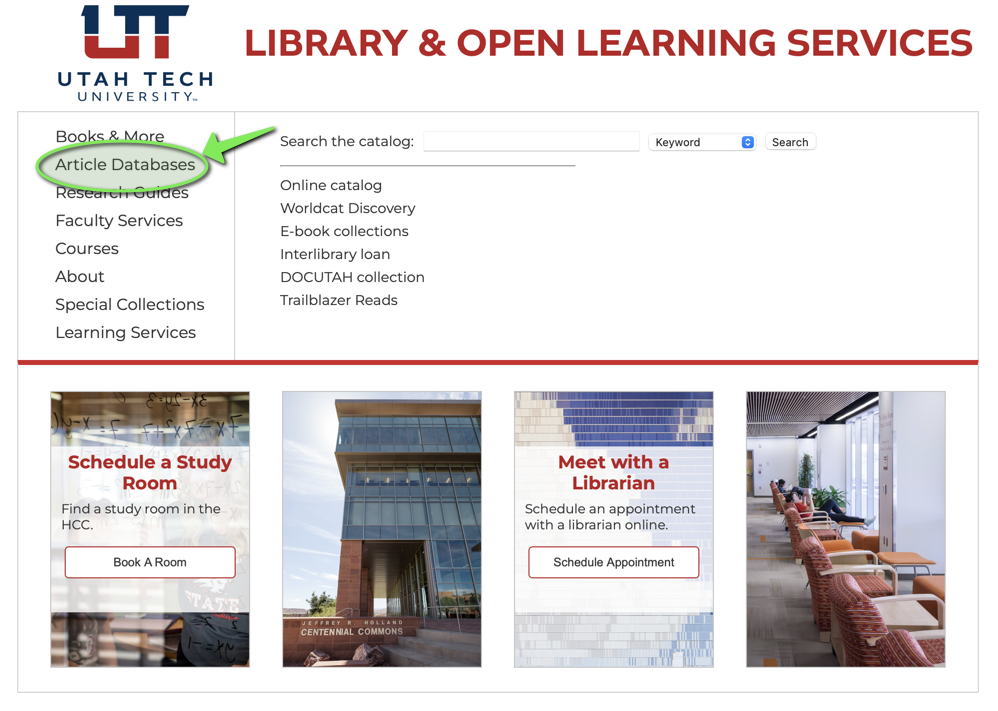

Third, click on “Subject List”:

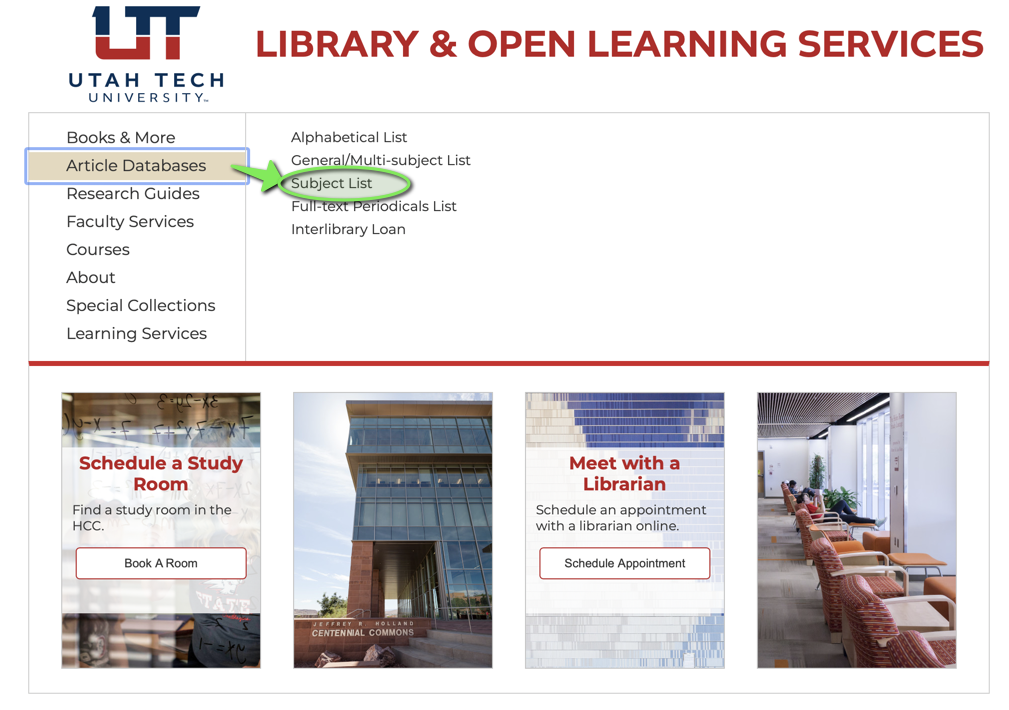

Fourth: Select subject of “Medicine and Health”:

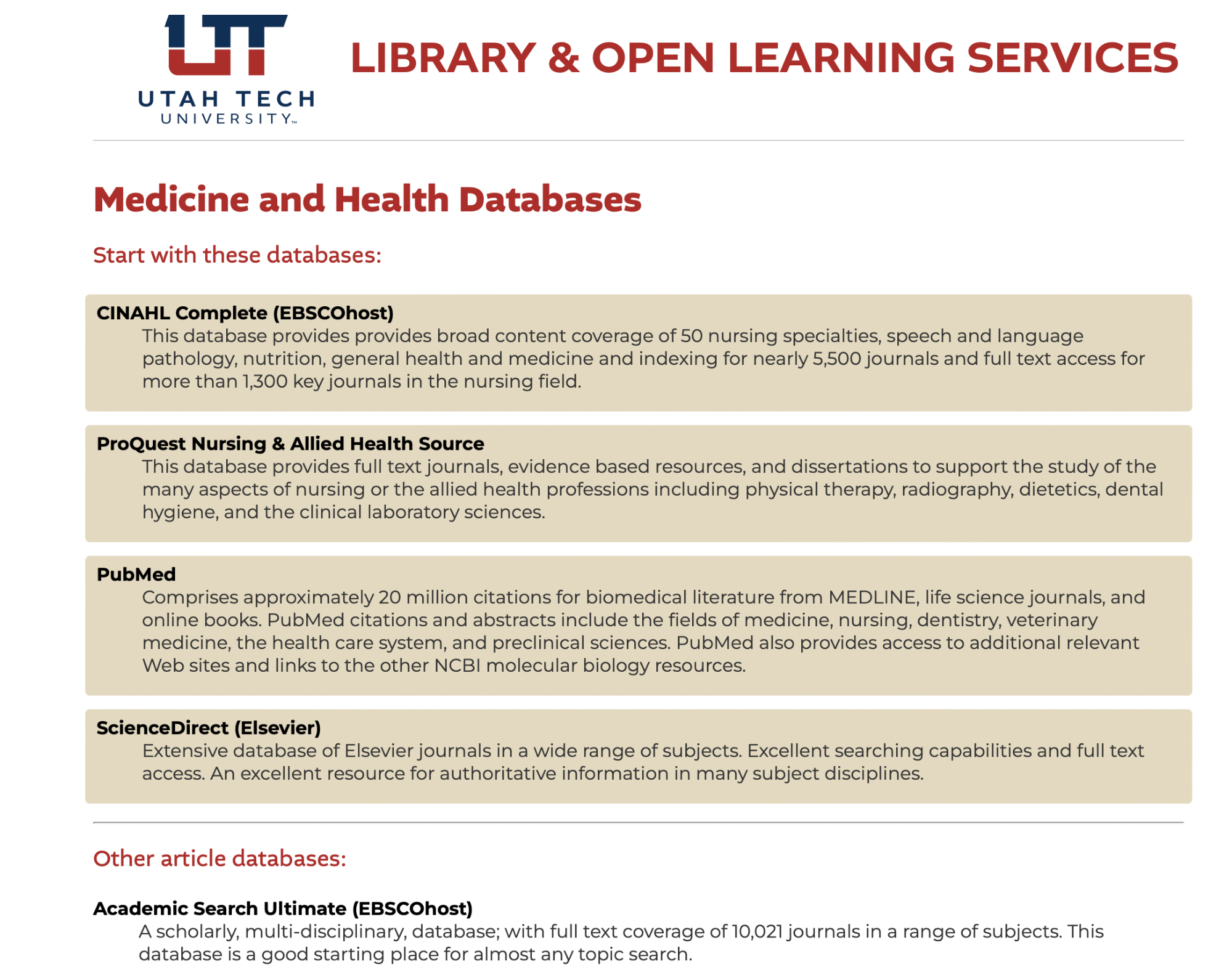

Fifth: This will take you to the databases. They are already in order of most helpful for nurses! That’s wonderful! CINAHL is specific to the nursing field and has a wealth of articles specific to evidence-based practice. ProQuest Nursing and Allied Health Source is also wonderful and very nursing specific.

Once you select the database, this will take you to some advanced options. Before we watch a couple tutorials on that (for CINAHL and PubMed), let’s chat about some search terms and phrases to begin you search.

Keywords and Phrases

Before applying advanced search techniques like Boolean operators or MeSH terms, it is essential to develop a strong foundation using keywords and key phrases. Keywords form the backbone of a literature search and help retrieve relevant studies in nursing and healthcare databases. Selecting the right terms, synonyms, and variations ensures a more comprehensive and effective search process.

This textbook has included an Appendix A2, titled “The Evidence-Based Practice Question Development & Search Tips Checklist” for your assistance in developing your clinical question and starting your literature search. This would be an excellent time to pull that up. You are expected to use this document to guide you as you work on your project.

There are three major strategies to use when searching for applicable evidence to help answer a clinical question: Keywords, subject headings, and title searching. They each have their strengths and weaknesses. There is no perfect search! It takes various methodologies to find the articles that are most pertinent for your clinical question.

A keyword search involves identifying the most important words or concepts related to a research question. To develop a strong search strategy, consider the following:

1. Identify the Core Concepts

- Break the research question into key components.

- Example research question:

“How does physical activity impact mental health in elderly patients?”

Core Keywords: physical activity, mental health, elderly patients

2. Consider Synonyms and Related Terms

- Different studies may use different terminology, so incorporating synonyms improves the chances of finding relevant research.

- Example:

| Original Keyword | Synonyms & Related Terms |

| Physical activity | exercise, fitness, movement, aerobic activity, walking |

| Mental health | psychological well-being, emotional health, depression, anxiety |

| Elderly patients | older adults, aging individuals, aged, seniors, geriatric population |

3. Use Broad and Specific Terms

- Broader terms retrieve more results, while specific terms focus on precise topics.

- Example:

- Broad search: “cancer” (retrieves all types of cancer)

- Narrow search: “breast cancer” (retrieves only studies on breast cancer)

Here is a handy table that shows the strengths and weaknesses of the three types of search strategies:

|

Search Strategies |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

Keyword Search |

|

|

|

Subject Headings Search |

|

|

|

Title Search |

|

|

(Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2015)

Now, when you enter a keyword into a search field in any database, the search will be launched into both a subject search and a textword search. A textword search looks for the keyword that you entered within the text fields of its records. In other words, it will look for that keyword in the title and the abstract. Now, remember above where it was mentioned that databases use coding systems? If you search for lung cancer, the search would retrieve citations coded for the subject code of lung neoplasms. Additionally, it would also retrieve any entries in which the phrase lung cancer appeared even if it had not been coded as lung neoplasm in subject heading (Polit & Beck, 2021).

Truncation

Truncation or wildcard symbols help to eliminate the need to search for plurals or a variant ending to a word. It greatly enhances your chance to find relevant studies. To truncate a word, part of a word is followed by an asterisk (*). For example, to find all versions of the word “nurse”, one would enter “nurs*” and then would result in: nurse, nurses, nursing. If one entered “foli*”, results would include “folic”, “foliage”, “folies”, etc. Some databases utilize truncation just a little differently, so be sure to know how to use truncation in whatever database you are searching. Sometimes a question mark (?) is used instead of an asterisk.

✅ Truncation (*) – Finds words with various endings.

Example: nurs* → Retrieves nurse, nurses, nursing

Example: child* → Retrieves child, children, childhood

✅ Wildcard (? or $) – Replaces a single character to account for spelling variations.

Example: wom?n → Retrieves woman, women

✅ Phrase Searching (“”) – Ensures the search retrieves exact phrases rather than separate words.

Example: “mental health” → Retrieves results where both words appear together, rather than separately.

Combining Keywords for a Stronger Search

To refine searches further, combine different keyword strategies:

- Start Broad → Search with general terms (nursing AND stress).

- Narrow Down → Add specific terms (nursing AND work-related stress).

- Refine with Synonyms → Use variations (nursing OR registered nurse AND burnout).

- Use Truncation → Retrieve multiple word forms (nurs* AND “job satisfaction”*).

✅ Example Search Query in PubMed:

📌 (“exercise”[Title/Abstract] OR “physical activity”[MeSH]) AND (“mental health”[MeSH] OR “psychological well-being”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“elderly”[MeSH] OR “older adults”[Title/Abstract])

This approach ensures a thorough search by incorporating different terminology, subject headings, and keyword variations.

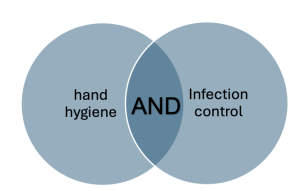

Boolean Operators

Boolean operators are simple words—AND, OR, NOT—that help structure search queries for better accuracy. By strategically combining Boolean operators, researchers can focus their searches and reduce irrelevant results. Boolean operators function as connectors between search terms, modifying how a database retrieves and displays results.

Boolean operators function as connectors between search terms, modifying how a database retrieves and displays results. Different operators serve different purposes:

- AND – Narrows the Search

The AND operator retrieves only results that contain all specified terms, reducing the number of articles and ensuring greater relevance. It is particularly useful when searching for studies that address multiple aspects of a topic.

✅ Example:

📌 hand hygiene AND infection control

This search retrieves only articles that discuss both hand hygiene and infection control, excluding studies that mention only one of the terms. Therefore, it narrows the search.

- OR – Broadens the Search

The OR operator retrieves results that contain at least one of the specified terms, making it useful for expanding a search by including synonyms or related concepts. This is particularly beneficial when different terms may be used for the same concept in literature.

✅ Example:

📌 nurse OR clinician OR healthcare provider

This search retrieves articles that contain any of these terms, increasing the number of results. Therefore, it broadens the search.

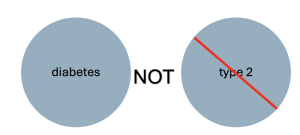

- NOT – Excludes Irrelevant Results

The NOT operator removes results that contain the specified term, which helps eliminate articles that may be related to, but not relevant for, a search query. However, use NOT cautiously to avoid unintentionally omitting useful studies.

✅ Example:

📌 diabetes NOT type 2

This search retrieves articles about diabetes excluding those specifically focused on type 2 diabetes. Therefore, it narrows the search.

Boolean Operators in Action

To illustrate how Boolean operators can refine a literature search, consider the following research question:

“What are the effects of telehealth on patient satisfaction in nursing care?”

A simple keyword search might yield too many irrelevant results, but applying Boolean operators refines the search:

| Boolean Search Query | Effect on Search Results |

| telehealth AND “patient satisfaction” | Retrieves studies that include both telehealth and patient satisfaction in their findings. |

| telehealth OR “virtual care” OR “remote monitoring” | Expands the search to include articles using different terms for telehealth. |

| telehealth AND “patient satisfaction” NOT pediatrics | Narrows the search by excluding studies focused on pediatric populations. |

- Use AND to narrow broad searches and focus on highly relevant studies.

- Use OR to include synonyms and broaden searches to avoid missing valuable articles.

- Use NOT cautiously to filter out unwanted topics without accidentally omitting key studies.

- Combine operators strategically for complex searches (e.g., (“telehealth OR virtual care”) AND (“patient satisfaction”) NOT (pediatrics OR neonatal)).

- Test and refine searches by adjusting terms and operators based on initial search results.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Keyword Searches

In databases like PubMed and CINAHL, controlled vocabularies such as MeSH terms help standardize searches and improve accuracy. Unlike simple keywords, MeSH terms categorize research topics under a consistent framework, reducing ambiguity. For example, a keyword search for “heart attack” might miss articles using the term “myocardial infarction,” but a MeSH-based search will retrieve all relevant studies regardless of terminology. MeSH is a controlled vocabulary developed by the U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM) to standardize indexing and classification of biomedical literature. Unlike simple keyword searches, which may retrieve articles with unrelated terms, MeSH terms help users find studies that are conceptually relevant, regardless of variations in terminology. Additionally, researchers should combine MeSH terms with keyword searches to ensure comprehensive coverage of all relevant articles.

Using MeSH terms improves literature searches in several ways:

✅ Standardization: Ensures consistency by grouping similar concepts under a single heading.

✅ Improved Accuracy: Helps eliminate irrelevant results caused by keyword ambiguity.

✅ Hierarchical Structure: Organizes terms from broad to specific, allowing for targeted searches.

✅ Automatic Mapping: In PubMed, for example, keywords often automatically map to MeSH terms, improving search effectiveness.

How MeSH Terms Work in PubMed

In PubMed, each article is indexed with specific MeSH terms that reflect its core topics. MeSH terms are arranged in a hierarchical structure, with broader categories at the top and more specific subcategories below.

Example: Searching for Diabetes in PubMed

Suppose a nurse researcher is interested in diabetes management. A simple keyword search using “diabetes” may retrieve irrelevant articles, including those about diabetes insipidus (a different condition). However, using MeSH terms ensures precision.

Step 1: Find the MeSH Term for Diabetes

- In PubMed, go to the MeSH Database and search for diabetes mellitus.

- The official MeSH term is “Diabetes Mellitus”, with narrower terms like “Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus” and “Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus” listed beneath it.

Step 2: Use the MeSH Term in a Search

- Instead of typing just diabetes, enter:

- “Diabetes Mellitus”[MeSH]

This ensures PubMed retrieves articles specifically indexed under this concept.

Step 3: Use Subheadings to Focus the Search

- MeSH terms can be combined with subheadings to refine results.

- For example:

“Diabetes Mellitus/therapy”[MeSH] → Focuses on treatment-related articles.

“Diabetes Mellitus/prevention & control”[MeSH] → Finds articles on prevention strategies.

MeSH Structure for “Diabetes Mellitus”:

📂 Diabetes Mellitus [MeSH]

📄 Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus [MeSH]

📄 Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus [MeSH]

📄 Prediabetes [MeSH]

📄 Gestational Diabetes [MeSH]

This hierarchical structure allows researchers to broaden or narrow their search depending on their specific research question.

Researchers can combine MeSH terms with Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) and other PubMed features to enhance searches:

✅ Combining Multiple MeSH Terms

📌 “Diabetes Mellitus”[MeSH] AND “Exercise Therapy”[MeSH] → Finds studies on diabetes and exercise therapy.

✅ Using Exploded MeSH Searches

📌 “Diabetes Mellitus”[MeSH:exp] → Retrieves articles indexed with diabetes mellitus and all its subcategories, ensuring broader coverage.

✅ Restricting to Major MeSH Topics

📌 “Diabetes Mellitus”[MeSH:Majr] → Retrieves only articles where diabetes is the primary focus, filtering out less relevant results.

Practical Application of MeSH in Nursing Research

For a nursing student researching the effects of telehealth on chronic disease management, using MeSH terms in PubMed would improve search accuracy:

✅ Keyword-Based Search (Less Effective)

📌 telehealth AND chronic disease

❌ Issues: May retrieve articles using different terminology (e.g., remote care, virtual visits).

✅ MeSH-Based Search (More Effective)

📌 (“Telemedicine”[MeSH] AND “Chronic Disease”[MeSH])

✔️ Benefits: Ensures that only articles indexed under telemedicine and chronic disease are retrieved, improving relevance.

Applying Filters and Advanced Search Options.

Most databases allow users to refine their search results using filters such as:

Publication Date – To find the most recent research (e.g., last five years).

Study Type – To focus on systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, or qualitative studies. This helps eliminate extraneous results such as books, editorials, or informational articles.

Full Text Availability – To access complete articles rather than abstracts only.

Population or Age Group – To narrow results to pediatric, adult, or geriatric studies.

By applying filters, researchers can quickly identify studies that best match their research needs.

All EBP projects should be based on current information. Most scholars use five to seven years as the time frame for what is considered current. Some scholars use five years, and some use ten years. For the sake of the EBP project for this course, 10 years is the extreme limit. Five years is a much safer timeframe to use.

Lastly, as noted above, be wary when limiting searches to full-text. If you have a result in which the article seems helpful in answering your question, there is the option of interlibrary loan. Watch the tutorial for help in gaining access to articles. Never pay money for an article access. We have the university library at your fingertips to assist you in obtaining the full article!

Now that we have formulated our PICO and we know how to search for articles, start searching on your own and find 10-12 articles to start with and keep track of these on your Synthesis of Evidence Worksheet.

You will also need to keep a record of your methodologies (search strategies) in finding the most relevant articles. Remember, your instructor should be able to duplicate your search strategy and find the same articles (or very close to it). Your methodology should be able to be duplicated by others.

Keep track of the following search strategy methodologies as a minimum:

- Databases

- Keywords

- Limiters

- Boolean operators

- Result numbers

Here is a very helpful website that may help you to visualize how to insert your search terms in a database (in their example, CINAHL):

https://simmons.libguides.com/c.php?g=1033284&p=7490077

Here is a tutorial about searching in CINAHL: Searching CINAHL (Academic)

EBSCO. (2020). Searching CINAHL (Academic). https://vimeo.com/403791714

Here is another tutorial about searching in PubMed: Searching PubMed, https://libguides.ohsu.edu/ebptoolkit/levelsofevidence

Citation Tracking and Reference Management

Another useful technique is citation tracking, which involves examining the references of a relevant article to find additional sources on the same topic. Many databases provide “cited by” links that show newer studies referencing a particular article, helping researchers follow the progression of knowledge in a field.

In the process of conducting a comprehensive literature search, researchers often use an ancestry approach to identify additional relevant studies. This technique involves examining the reference lists of key articles to trace prior research and build upon existing knowledge. By following citation trails, nursing students and healthcare professionals can uncover foundational studies, influential theories, and supporting evidence that may not appear in initial database searches.

The ancestry approach is based on the idea that each published study is built upon previous research. By tracing references cited in a study, researchers can find earlier work that contributed to the topic. This is particularly useful in identifying seminal or foundational studies that shaped a field of research, highly relevant articles that may not appear in keyword-based searches, theoretical frameworks that underpin a research question, and gaps in literature where further investigation is needed.

In contrast to the ancestry approach, researchers can also use a descendancy approach, which focuses on finding newer studies that cite an existing key article. This technique helps researchers track how a topic has evolved over time and identify recent advancements in the field.

Practical Application: Ancestry Approach

A nursing student researching the impact of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on nurse burnout finds a recent systematic review on the topic. By examining the reference list, the student identifies original clinical trials that tested MBSR interventions, leading to more primary sources of evidence.

Evaluating the Quality of Evidence

Finding relevant literature is only the first step in the evidence-based practice (EBP) process. Once sources are gathered, it is essential to critically evaluate their quality, credibility, and applicability to ensure that clinical decisions are based on the most reliable and valid research. High-quality evidence strengthens nursing practice by minimizing bias, improving patient outcomes, and supporting the development of guidelines and policies. Not all results are equally good! Keep that in the back of your mind as you start evaluating the quality of the studies that you find. Several factors must be considered when assessing the quality of evidence, including credibility, reliability, validity, relevance, and bias.

Table: Evaluating the Quality of Evidence

| Criterion | Description | Questions to Ask |

| Credibility | Determines if the source is trustworthy and published in a reputable journal. | Is the study published in a peer-reviewed journal? Is the author an expert in the field? |

| Reliability | Assesses whether the study’s findings are consistent and reproducible. | Would similar results be obtained if the study were repeated? Were standardized methods used? |

| Validity | Examines if the research truly measures what is claims to measure. | Are the study design and methods appropriate for answering the research question? |

| Relevance | Determines if the study is applicable to the specific clinical issue or patient population. | Does the study address the nursing problem of interest? Are the findings transferable to practice? |

| Bias | Investigates whether any systematic errors could affect the study’s outcomes. | Is there potential conflict of interest? Were funding sources disclosed? Were the researchers blinded? |

Systematic and Scoping Reviews

In nursing and healthcare research, systematic and scoping reviews play a crucial role in synthesizing existing evidence. These types of reviews go beyond individual studies by providing comprehensive summaries of the literature on a given topic. Understanding their differences, purposes, and applications helps researchers and clinicians make informed decisions based on the best available evidence.

What is a Systematic Review?

A systematic review is a structured, methodical synthesis of existing research that seeks to answer a specific research question. It follows a rigorous, predefined protocol to ensure transparency, minimize bias, and enhance reproducibility. Systematic reviews are considered high-quality evidence in evidence-based practice because they compile findings from multiple studies to provide a more reliable conclusion.

Key Characteristics of a Systematic Review:

Focuses on a clearly defined research question (e.g., “Does nurse-led patient education improve medication adherence?”).

- Uses comprehensive and reproducible search strategies across multiple databases.

- Applies strict inclusion and exclusion criteria to select relevant studies.

- Conducts critical appraisal to assess the quality and risk of bias in included studies.

- Often includes a meta-analysis, which statistically combines the results of multiple studies to generate a pooled estimate of effect.

Practical Application: Systematic Review

A systematic review might examine multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the effectiveness of hand hygiene compliance programs in reducing hospital-acquired infections. The review would analyze findings from these trials, assess their methodological quality, and synthesize results to determine whether such programs are truly effective.

What is a Scoping Review?

A scoping review is broader in scope than a systematic review and is used to map the available evidence on a topic rather than answer a specific research question. It is particularly useful when little is known about a subject, allowing researchers to identify key concepts, gaps in the literature, and areas for further study.

Key Characteristics of a Scoping Review:

Aims to explore the breadth of literature rather than answer a narrow research question.

- Uses broad search criteria to identify studies across various disciplines.

- Does not typically assess study quality or conduct a meta-analysis.

- Helps define concepts, trends, and gaps in research.

Practical Application: Scoping Review

A scoping review might investigate how virtual reality is being used in nursing education across different populations and settings. Instead of evaluating the effectiveness of a single intervention, it would compile studies on various applications, identifying trends, challenges, and areas needing further research.

Table: Comparison of Systematic Review vs. Scoping Review

| Feature | Systematic Review | Scoping Review |

| Purpose | Answers a specific research question. | Maps existing research on a broad topic. |

| Search Strategy | Comprehensive and predefined. | Broad and exploratory. |

| Study Selection Criteria | Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. | More flexible criteria. |

| Quality Appraisal | Evaluates study quality and bias. | Does not assess quality. |

| Meta-analysis | Often included. | Not included. |

| Outcome | Provides a definite answer to a research question. | Identifies gaps, trends, and concepts. |

Applying Literature Searches to Clinical Practice

The ultimate goal of searching for evidence in literature is to improve clinical decision-making and patient care. Evidence-based practice (EBP) relies on the ability to locate, evaluate, and integrate high-quality research into real-world healthcare settings. By effectively applying findings from literature searches, nursing professionals can enhance patient outcomes, develop clinical guidelines, and contribute to the advancement of nursing knowledge.

A well-executed literature search provides scientific evidence to support nursing interventions, but applying that evidence requires careful consideration of its relevance, feasibility, and impact on patient care. The process involves:

Identifying Clinical Problems and Questions – Nurses recognize issues in practice that need improvement, such as reducing hospital-acquired infections or improving pain management.

Finding the Best Available Evidence – Literature searches uncover research that addresses these issues, helping nurses evaluate different interventions.

Assessing Applicability to Patient Care – Not all research findings are directly transferable to every clinical setting. Nurses must consider factors like patient preferences, available resources, and institutional policies.

Integrating Evidence with Clinical Expertise – Research should complement, not replace, professional judgment. Nurses use their experience and patient-centered care approaches to apply findings appropriately.

Evaluating Outcomes – Once evidence-based changes are implemented, ongoing assessment ensures that they lead to positive patient outcomes.

Citing and Referencing Sources

This bring us to “APA formatting”. As you already know, when utilizing information from a source (internet, book, article, etc.) you must cite and reference the source in order to give credit to the original author. “APA” stands for the American Psychological Association who have established the standard of procedure with regard to the process of signifying original authors’ content as well as providing procedures for academic and profession writing. The APA Style is a set of guidelines for clear and precise scholarly communication that helps authors achieve excellence in writing.

The American Psychological Association (APA) formatting style serves several important purposes in academic and professional writing:

- Clarity and Consistency: APA formatting provides a standardized structure for academic papers, ensuring a consistent and clear presentation of ideas. This uniformity makes it easier for readers to navigate and understand the content.

- Credibility and Academic Integrity: Following APA guidelines demonstrates a commitment to academic integrity and professionalism. It shows that the writer has taken the time to present their work in a standardized, recognized format widely accepted in the academic community.

- Communication of Ideas: APA formatting includes specific elements like in-text citations and a reference list, which help in properly crediting and acknowledging sources. This promotes transparency and allows readers to trace the origins of ideas and information presented in the paper.

- Facilitation of Review and Replication: For scholarly research, APA formatting aids in the review and replication of studies. By providing clear and organized information about research methods, results, and references, researchers can more effectively evaluate and build upon existing work.

- Publication Standards: Many academic journals and publications require submissions to adhere to APA formatting. Understanding and applying APA guidelines increase the likelihood of acceptance for publication, as it aligns the manuscript with the expectations of editors and peer reviewers.

- Cross-disciplinary Communication: APA formatting is widely used not only in psychology but also in various other social sciences and disciplines. Using a common format facilitates communication and understanding across different fields of study.

- Prevention of Plagiarism: The inclusion of proper citations and references in APA formatting helps to prevent plagiarism. It ensures that authors give credit to the original sources of information, ideas, or data, maintaining academic honesty.

- Professional Presentation: APA formatting includes guidelines for font size, margins, and other layout elements, contributing to a polished and professional appearance of the document. This enhances the overall impression of the writer’s work.

You will find resources in the Appendices that I have available for you in Canvas to assist you with how to format in-text citations and full reference citations (for a reference list) in Appendix D2 and Appendix E2. We will focus on how to format in-text citations and references for scholarly journal articles in this course. Your other upcoming courses may require that you also know how to cite and reference other types of published works. You will for sure be required to know APA formatting during your 4th semester, so spend the time to learn it now. If do recommend buying the spiral-bound APA Style Manual as a resource. Here is a link for you: https://apastyle.apa.org/products/publication-manual-7th-edition

If you proceed with a graduate degree, you will need to be near-expect level at APA as most graduate schools assume that you have learned this type of formatting at the undergraduate level.

We will work on formatting styles in class. However, there is one major key element that you need to memorize now: If you have an in-text citation, you must list the source as a full reference as well. And, vice versa. This is standard and must be utilized for any writing, assignments, projects, and any other type of work that you produce.

A few other tenants of APA formatting include:

- References should be in alphabetical order according to last name of the first author of a published work

- Difference sources (books, articles, websites, etc.) have different formats

- For in-text citations, APA utilized the author-date citation system (Author, Year)

- In-text citations that utilize direct quotations must include page numbers

APA formatting serves as a set of guidelines designed to improve the clarity, consistency, and professionalism of academic and professional writing. It promotes ethical conduct, aids in effective communication, and aligns with the standards of scholarly publishing.

Finally, as you start compiling articles to help answer your clinical question, you will need to keep track of these on a Synthesis of Evidence Table (see Appendix H), for which you will need to turn in. Use the Search Strategy Table to assist with your search. Be sure to check the format of the full references on the synthesis table as you proceed. This will help save some time when it gets closer to submitting the assignment.

In summary, conducting a thorough literature search is a fundamental skill in evidence-based nursing practice. By systematically identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing research, nurses and students can ensure that their clinical decisions are informed by the best available evidence. Understanding how to navigate databases, refine search strategies, assess the hierarchy of evidence, and critically appraise research findings allows for a more precise and effective integration of knowledge into practice. Whether searching for primary studies, systematic reviews, or clinical guidelines, mastering the literature search process helps bridge the gap between research and real-world patient care.

Applying literature searches in clinical settings is essential for improving healthcare outcomes, advancing nursing policies, and driving innovation in patient care. Nurses who incorporate research into their practice contribute to a culture of continuous learning and improvement, ensuring that interventions are based on validated evidence rather than outdated traditions. By staying engaged with the latest literature, advocating for evidence-based changes, and fostering a critical approach to research, nursing professionals uphold the highest standards of practice and enhance the quality of care for the patients they serve.

Summary Points

Accessing literature is the second step in EBP, focusing on systematically finding the best evidence to answer clinical questions.

Peer-reviewed sources are preferred because they are reviewed by experts before publication, ensuring higher reliability and accuracy.

Three types of sources:

-

Primary – original research (RCTs, cohort studies, qualitative studies)

-

Secondary – synthesis of primary studies (systematic reviews, meta-analyses)

-

Tertiary – summaries for quick reference (textbooks, handbooks)

Research vs. non-research articles: Only true research articles (with methods, data, results) are valid for EBP projects; editorials, reviews, and informational pieces are not research.

Evidence hierarchy ranks research designs based on rigor and bias potential; systematic reviews and RCTs are high for intervention questions, but the best level depends on the research question type.

Database selection is critical—CINAHL, PubMed, Cochrane Library, JBI, and PsycINFO are top nursing research sources.

Search strategies should use multiple databases for comprehensive results.

Keywords should be derived from PICO components; synonyms, variations, and truncation expand retrieval.

Search strategies include keywords, subject headings (like MeSH), and title searches; each has strengths and weaknesses.

Boolean operators refine searches:

-

AND narrows results

-

OR broadens by adding synonyms

-

NOT excludes unwanted terms

MeSH terms in PubMed and similar subject headings in CINAHL improve precision by standardizing terms (e.g., “myocardial infarction” instead of “heart attack”).

Filters (date range, study type, population) ensure results are current, relevant, and specific to the research question.

Critical appraisal tools (CASP, JBI, GRADE) assess study quality, bias, and applicability.

Citation tracking (ancestry and descendancy approaches) helps locate additional relevant sources by following reference lists and cited-by links.

Systematic reviews synthesize multiple studies to answer specific research questions; scoping reviews map broader topics to identify trends and gaps.

Quality evaluation checks credibility, reliability, validity, relevance, and bias before applying findings to practice.

APA formatting ensures consistent citation of sources, giving proper credit and maintaining academic integrity.

Documenting the search strategy (databases, keywords, limiters, operators) ensures the process can be replicated.

Effective literature searching supports EBP by integrating the best evidence into clinical decision-making, improving patient outcomes, and guiding nursing practice.

Ponder This

A new graduate nurse, Emily, is eager to apply evidence-based practice in her clinical setting. While caring for an elderly patient with chronic heart failure, she recalls a recent systematic review she read, which suggests that daily weight monitoring, sodium restriction, and telehealth monitoring significantly reduce hospital readmissions. Wanting to ensure the best outcomes, she educates her patient on these strategies and collaborates with the care team to implement them.

However, Emily soon encounters challenges. The patient expresses difficulty adhering to dietary restrictions, as they live alone and rely on pre-packaged meals. Additionally, they have limited access to technology, making telehealth monitoring impractical. Despite strong evidence supporting these interventions, Emily realizes that patient-centered care requires balancing research findings with individual needs, resources, and social determinants of health.

- Consider how Emily should adjust her approach to ensure the patient benefits from evidence-based strategies while respecting their limitations and preferences.

- Reflect on what role nurses play in adapting research-based interventions to fit the realities of diverse patient populations.

![]() Hot Tip! The university librarians can obtain any article that you find and then email it to you. This can all be done online through the university library website page through the “Interlibrary Loan” link. Never pay for an article!

Hot Tip! The university librarians can obtain any article that you find and then email it to you. This can all be done online through the university library website page through the “Interlibrary Loan” link. Never pay for an article!

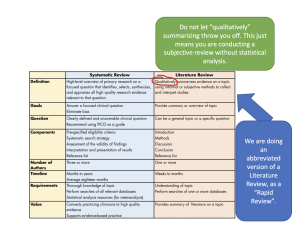

![]() Hot Tip! There is often confusion as to what constitutes a Systematic Review versus a Literature Review. In this course, we are performing a Rapid Literature Review (AKA: Rapid Review), but with the inclusion of a focused clinical question. When someone asks you what your EBP Project is all about, you can reply, “It is a rapid review of literature, but not a comprehensive systematic review.” Here is a handy table that explains the differences.

Hot Tip! There is often confusion as to what constitutes a Systematic Review versus a Literature Review. In this course, we are performing a Rapid Literature Review (AKA: Rapid Review), but with the inclusion of a focused clinical question. When someone asks you what your EBP Project is all about, you can reply, “It is a rapid review of literature, but not a comprehensive systematic review.” Here is a handy table that explains the differences.

Case Study: Integrating Evidence-Based Practice to Reduce Hospital-Acquired Infections

A large urban hospital’s medical-surgical unit experienced an increase in hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) over a six-month period, leading to prolonged patient stays and higher healthcare costs. Nursing leadership identified that inconsistent hand hygiene compliance among staff could be a contributing factor. While existing hospital policies recommended standard handwashing protocols, observations and audit reports revealed gaps in adherence. The nursing team recognized the need to evaluate best practices in infection prevention and implement evidence-based strategies to improve compliance and patient safety.

Actions Taken

To address the issue, a team of nurse educators and infection control specialists conducted a literature search using CINAHL, PubMed, and the Cochrane Library to identify the most effective interventions for increasing hand hygiene compliance. The search focused on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews evaluating hand hygiene education, monitoring systems, and behavioral reinforcement strategies. Findings indicated that real-time electronic monitoring, visual reminders, and staff education programs significantly improved compliance rates in hospital settings.

Based on this evidence, the hospital implemented a multi-faceted intervention plan, including:

- Hand hygiene refresher training for all nursing and healthcare staff, incorporating research-based techniques.

- Electronic hand hygiene monitoring systems with real-time feedback to track adherence.

- Strategic placement of visual reminders near patient rooms, workstations, and sinks.

- Peer accountability initiatives, where nurses provided positive reinforcement and reminders to colleagues.

Results

Within three months of implementation, compliance with hand hygiene protocols increased from 65% to 92%, as measured by electronic monitoring and direct observation audits. The rate of HAIs decreased by 35%, leading to improved patient safety and a reduction in the average length of hospital stays. Additionally, staff engagement in infection prevention efforts significantly improved, with nurses taking a more active role in ensuring compliance across the unit.

Conclusion

By integrating evidence-based research into practice, the hospital successfully enhanced hand hygiene adherence and reduced infection rates. The case highlights the importance of using literature searches to inform clinical decisions and implementing multi-strategy interventions to address healthcare challenges. Through continuous monitoring and reinforcement, the hospital sustained long-term improvements in infection control, demonstrating the power of evidence-based practice in optimizing patient outcomes.

References & Attribution

“Green check mark” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

“Light bulb doodle” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

“Orange flame” by rawpixel licensed CC0.