The First Step: Establishing the Problem and Asking the Question

In this chapter, we will learn about identifying the problem, start the “Ask” process with developing an answerable clinical question, and learn about purpose statements and hypotheses.

Content includes:

- Identifying/determining the problem

- Determining the Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO)

- Asking a compelling Research/Clinical Question (Based on PICO)

- Statements of Purpose

- Hypotheses

Objectives:

- Discuss the process of recognizing and articulating a clinical or research problem that is significant to nursing practice.

- Determine well-structured clinical questions that guide evidence-based practice and address specific nursing issues.

- Explain the components of PICOT (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Time) and distinguish between different types of PICOT questions used in clinical research.

- Understand the role and structure of a statement of purpose in a research study, including how it aligns with research questions and hypotheses.

- Construct a well-defined hypothesis.

- Evaluate the relevance of clinical questions and hypotheses in research.

- Analyze examples of clinical questions, purpose statements, and hypotheses.

Key Terms:

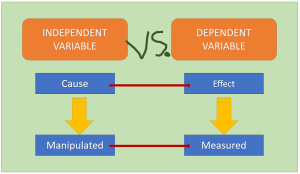

- Dependent variable: This is the variable that we utilize statistical analyses to measure, and for which is not manipulated.

- Hypothesis: A specific, testable prediction about the expected outcome of a study.

- Independent variable: This is a measure that the researcher can manipulate.

- Knowledge-focused triggers: These problems are identified through reading published evidence or learning new information at conferences or other professional meetings.

- PICO(T): The foundation of a clinical question: Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Time.

- Problem statement: The underlying issue that the researcher wants to explore.

- Problem-focused triggers: These problems are identified by staff during routine monitoring of quality, risk, adverse events, financial, or benchmarking data.

- Statement of purpose: A concise declaration that outlines the main aim or intent of a study.

Introduction

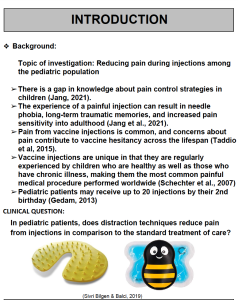

Every research study starts with a problem the researcher wants to solve. Establishing a clinical nursing problem is the first crucial step in developing an evidence-based practice (EBP) or research inquiry. Identifying a problem begins with observing recurring issues, inefficiencies, or variations in patient outcomes during clinical practice. For example, a nurse might notice a high incidence of pressure ulcers in a particular unit despite routine preventive measures. Recognizing this as a clinical problem, the nurse can then formulate a focused clinical question to guide further investigation.

As an entry-level nursing students, jumping into the world of evidence-based practice (EBP) begins with understanding how to identify and develop a research problem. The research problem is the foundation of any study, guiding the research process and ultimately influencing the outcomes. But what exactly is a research problem?

A research problem is a specific issue, difficulty, gap in knowledge, or concern that a researcher aims to address through systematic investigation. It often arises from clinical practice, patient experiences, or gaps identified in current, existing literature.

Without up-to-date evidence, clinical practices can quickly become outdated, which can harm our patients. For instance, for many years, pediatric providers advised parents to place their infants on their stomachs (prone position) while sleeping. This was believed to be the best way to prevent choking if the baby vomited. However, as more evidence became available, it was found that sleeping on the stomach actually increases the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). In response, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a guideline recommending that infants should sleep on their backs (supine position) instead. This change led to a significant decrease in SIDS cases (AAP, 2000). In this example, the underlying problem was increasing SIDS.

Determining the Problem

For a problem to be researchable, it needs to be something that can be studied by collecting and analyzing data. Some problems, even if they are interesting, are not suitable for research because they can’t be studied this way. For instance, moral or ethical issues are not researchable because their solutions depend on personal values. An example of this is the question, “Is it morally acceptable to perform genetic modifications on human embryos?” The answer depends on individual values and doesn’t have a clear right or wrong answer. This question deals with personal values and beliefs about the ethics of altering human genetics, making it a moral or ethical issue rather than a researchable problem that can be studied through data collection and analysis.

However, you can research people’s opinions. For example, to turn the question “Is it morally acceptable to perform genetic modifications on human embryos?” into a researchable question, you could focus on studying opinions or outcomes related to genetic modifications. For example:

- “What are the attitudes of different demographic groups towards genetic modifications on human embryos?”

- “What are the potential health outcomes of genetic modifications on human embryos?”

- “How do medical professionals view the risks and benefits of genetic modifications on human embryos?”

- “What ethical concerns do people raise about genetic modifications on human embryos?”

These questions can be studied by collecting and analyzing data on people’s opinions, health outcomes, or professional perspectives.

The problem statement is the underlying issue that the researcher wants to explore. It should be broad enough to address the main concern but specific enough to guide the study’s design. The problem statement(s) are a key part of the study. The problem statement conveys the issues and context that gave rise to the study (McGaghie et al., 2001).

A problem statement explains an issue that needs to be addressed or a situation that needs improvement. It highlights the difference between the current state and the desired goal. The first step in solving a problem is to understand it, which is achieved through a clear problem statement (Polit & Beck, 2021). The general discussion of the issue leads up to the problem statement. The problem statement is then usually explained further by outlining the study’s purpose and goals, which are based on the problem statement.

Identifying a Research Problem

In the clinical setting, research problems often emerge from real-world nursing challenges. For example, imagine you’re working in a hospital where a significant number of patients are being readmitted within 30 days of discharge. You notice that many of these patients are older adults with multiple chronic conditions. This observation might lead you to wonder whether the current discharge planning process is effective in addressing the complex needs of these patients.

This is a potential research problem that could be explored further. The key here is that the problem is specific, relevant to clinical practice, and has the potential to improve patient outcomes. A question to ponder could include, “Does the current discharge planning process adequately prepare older adults with multiple chronic conditions to manage their health at home, reducing the risk of readmission?”

Article: Problem Statement in a research article (Bristol, 2021).

Example of a Problem Statement

Here is the introduction to the article titled, Early Ambulation in Hip Replacement Patients Regarding Length of Hospital Stay (Bristol, 2021). The problem statements are found in the Introduction. The author established that total hip replacement surgeries are one of the most common orthopedic surgeries, there is a need for high hospital turnover to keep up with demand, there was a study showing that early ambulation can decrease the length of inpatient stay, and that there is a need to reduce costs while improving patient outcomes.

Table: Examples of Research Problem Statements

| Research Area | Problem Statement | Potential Research Question |

| Nursing | Many ICU nurses experience high levels of burnout, leading to decreased job satisfaction and increased turnover rates, which may affect patient care quality. | How does nurse burnout in the ICU impact patient outcomes and job retention? |

| Mental Health | Adolescents with anxiety disorders often struggle with medication adherence, potentially reducing treatment effectiveness and increasing relapse rates. | What are the main barriers to medication adherence among adolescents with anxiety disorders? |

| Public Health | Vaccine hesitancy remains a significant public health issue, particularly among certain demographics, leading to lower immunization rates and increased disease outbreaks. | What factors contribute to vaccine hesitancy in specific populations, and how can targeted interventions improve immunization rates? |

| Education | Many nursing students report high levels of test anxiety, which may negatively affect academic performance and clinical decision-making skills. | How does test anxiety impact nursing students’ academic success and clinical judgment? |

| Healthcare Access | Rural communities often face significant barriers to healthcare access, including provider shortages, transportation difficulties, and financial constraints. | What are primary barriers to healthcare access in rural populations, and how do they affect patient outcomes? |

| Technology in Healthcare | The integration of electronic health records (EHRs) has streamlined patient data management, but many healthcare providers report challenges with system usability and increased documentation burden. | How does the usability of EHRs impact provider efficiency and patient care quality? |

| Women’s Health | Postpartum depression is a common but underdiagnosed condition, often leading to negative effects on maternal-infant bonding and overall family well-being. | What are the most effective screening methods for early detection of postpartum depression? |

Development of a Research/Practice Problem

Questions or concerns frequently arise from day-to-day problems that providers encounter (Dearholt & Dang, 2012). Often, these problems are very obvious. However, sometimes we need to back up and closely examine the status quo to see underlying issues. The basis for any research project is indeed the underlying problem or issue. The research priorities of the nursing profession, along with the interests of funding bodies focused on healthcare research, are key sources for identifying researchable problems (Grove & Gray, 2018). A good problem statement or paragraph declares what is problematic or what we do not know much about (a knowledge gap) (Polit & Beck, 2021).

For example, perhaps we have patients that are experiencing pain and we want to explore adjunctive or alternative methods to help manage pain. We might want to know if adjunct music therapy helps decrease postoperative pain levels than just pharmaceuticals alone. Therefore, we might consider the underlying problems of:

- Postoperative pain is not adequately managed in more than 80% of patients in the US, although rates vary depending on such factors as the type of surgery performed, analgesic/anesthetic intervention used, and time elapsed after surgery (Gan, 2017).

- Poorly controlled acute postoperative pain is associated with increased morbidity, functional and quality-of-life impairment, delayed recovery time, prolonged duration of opioid use, and higher healthcare costs (Gan, 2017).

- Multimodal analgesic techniques are widely used, but new evidence is disappointing (Rawal, 2016).

In the above examples, we establish that poorly managed postoperative pain is a problem. Thus, looking at evidence about adjunctive music therapy may help to address how we might manage pain more effectively.

The process of defining the practice/clinical problem begins by seeking answers to clinical concerns. This is the first step in the EBP process: To ask. We start by asking some broad questions to help guide the process of developing our practice problem.

- Is there evidence that the current treatment works?

- Does the current practice help the patient?

- Why are we doing the current practice?

- Should we be doing the current practice this way?

- Is there a way to do this current practice more efficiently?

- Is there a more cost-effective method to do this practice?

![]() Knowledge to application link.

Knowledge to application link.

Here is the introduction to the article titled, “The relationships among pain, depression, and physical activity in patients with heart failure” (Haedtke et al, 2017). You can read that the underlying problem is multifocal: 67% of patient with heart failure (HF) experience pain, depression is a comorbidity that affects 22% to 42% of HF patients, and that little attention has been paid to this relationship in patients with HF. The researchers have established the need for further research and why further research is needed.

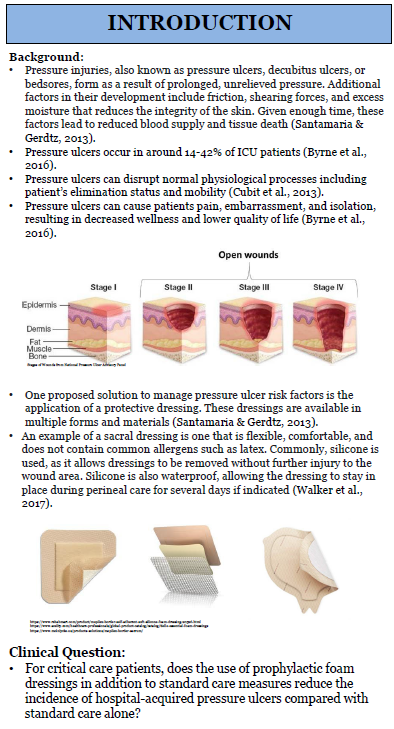

Here is another example of how the clinical problem is addressed in an EBP poster that wants to appraise existing evidence related to dressing choice for decubitus ulcers.

Ethical Considerations in Formulating a Research Problem

Ethical considerations are paramount when developing a research problem. As a nurse, your primary commitment is to the well-being of your patients. Therefore, your research or the problems you explore should always align with ethical principles such as beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice.

Consider a situation where you observe that patients from minority backgrounds are less likely to receive pain management interventions than others. This observation raises a significant ethical dilemma: Should you explore this issue further, knowing that your findings could highlight disparities that may lead to uncomfortable truths about biases in healthcare delivery?

Ponder This

How do you balance the need to uncover important truths in nursing practice with the potential discomfort or resistance such truths might provoke in your clinical setting?

Sources of Clinical Problems

When trying to communicate clinical problems, there are two main sources (Titler et al., 1994, 2001):

- Problem-focused triggers: These are identified by staff during routine monitoring of quality, risk, adverse events, financial, or benchmarking data.

- Knowledge-focused triggers: There are identified through reading published evidence or learning new information at conferences or other professional meetings.

Sources of Evidence-Based Clinical Problems:

|

Triggers |

Sources of Evidence |

|

Problem-focused |

|

|

Knowledge-focused |

|

Most problem statements have the following components:

- Problem identification: What is wrong with the current situation or action?

- Background: What is the nature of the problem or the context of the situation? (this helps to establish the why)

- Scope of the problem: How many people are affected? Is this a small problem? Big problem? Potential to grow quickly to a large problem? Has been increasing/decreasing recently?

- Consequences of the problem: If we do nothing or leave as the status quo, what is the cost of not fixing the issue?

- Knowledge gaps: What information about the problem is lacking? We need to know what we do not know.

- Proposed solution: How will the information or evidence contribute to the solution of the problem?

If you are stumped on a topic, ask faculty, RNs at local facilities, colleagues, and key stakeholders at local facilities for some ideas! There is usually “something” that the nursing field is concerned about or has questions about.

The First Step in the EBP Process: Asking Compelling Clinical Questions

The Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) process is a structured approach used in healthcare to ensure clinical decision-making is grounded in the best available evidence, combined with clinical expertise and patient preferences. This five-step process—Ask, Acquire, Appraise, Apply, and Analyze/Adjust—guides nurses in integrating research findings into practice, ultimately improving patient outcomes and healthcare quality.

The process begins with Ask, where a clear and focused clinical question is formulated using frameworks such as PICO(T) (Patient/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Time – we will come back to this in the next section). This ensures that the research inquiry is specific and relevant to patient care. Next, in the Acquire stage, practitioners search for high-quality evidence from reputable sources, including peer-reviewed journals, clinical guidelines, and systematic reviews. This step requires strong literature search skills to find the most relevant and reliable data.

Once evidence is gathered, the Appraise step involves critically evaluating the quality, credibility, and applicability of the research. Not all studies provide strong evidence, so healthcare professionals must assess factors like study design, sample size, validity, and bias before integrating findings into practice. Following the appraisal, the Apply phase involves implementing the evidence-based intervention in a clinical setting while considering patient preferences, available resources, and institutional policies.

The final step, Analyze/Adjust, ensures continuous improvement in practice. Healthcare providers evaluate patient outcomes, monitor the effectiveness of the intervention, and adjust approaches as needed. This cyclical nature of EBP allows for ongoing refinement, ensuring that clinical care remains current, effective, and patient-centered. By following this process, nurses and other healthcare professionals can enhance care quality, improve patient safety, and contribute to a culture of lifelong learning and clinical excellence.

Therefore, once you’ve identified a research problem, the next step is to transform it into a researchable question. A well-formulated research question is clear, focused, and feasible. The process of defining the practice/clinical problem is followed by seeking answers to clinical concerns. This is the first step in the EBP process: To ask.

- Is there evidence that the current treatment works?

- Does the current practice help the patient?

- Why are we doing the current practice?

- Should we be doing the current practice this way?

- Is there a way to do this current practice more efficiently?

- Is there a more cost-effective method to do this practice?

We will need to ask these questions and see what literature exists to help answer them. This establishes the “background” of the issue we want to know more about. Writing a research question for a study is critical. They serve as the foundation for the entire research process. Clear and well-defined research questions help to provide a direction and focus, ensuring that the research stays on track and addresses specific issues or problems. They also help determine the research methodology, including data collection and analysis methods, and ensure that the study is appropriately structured.

Research questions also:

- Clarify Objectives: The research question helps outline what the researcher hopes to achieve, clarifying the study’s goals and purpose.

- Identify Variables: They help in identifying and defining the variables to be studied, which is essential for data collection and analysis.

- Provide a Framework: They offer a framework for organizing the study, helping to systematically address the research problem and make logical conclusions.

- Enhance Relevance: They also ensure that the study addresses pertinent and meaningful issues, making the research valuable to the field.

We do use a clinical question for research as well as quality improvement projects, but the steps are a bit different. Research questions can be used to guide both quantitative and qualitative studies.

By identifying specific clinical problems and forming focused clinical questions, nurses can seek out evidence-based solutions to improve patient care and outcomes.

Examples of Clinical Nursing Problems and Resulting Clinical Questions

- High Incidence of Falls in Elderly Patients

Clinical Problem: A 43% increase in the number of falls among elderly patients in a hospital unit over the past year.

Potential Clinical Question: In elderly patients in a hospital setting, how does the implementation of a fall prevention program compared to standard care affect the incidence of falls over six months?

- Poor Pain Management in Postoperative Patients

Clinical Problem: Of the 145 postoperative patients at a hospital, 37 report inadequate pain control despite following standard pain management protocols.

Potential Clinical Question: In postoperative patients, how does the use of a multimodal pain management approach compared to opioid-only management affect pain levels within the first 48 hours after surgery?

- Delayed Wound Healing in Diabetic Patients

Clinical Problem: There have been increasing incidents of diabetic patients experiencing slower wound healing rates compared to non-diabetic patients.

Potential Clinical Question: In diabetic patients with chronic wounds, how does the application of advanced wound dressings compared to standard wound care affect the rate of wound healing over three months?

- High Rates of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTIs)

Clinical Problem: An 80% increase in the number of CAUTIs in a hospital unit.

Potential Clinical Question: In hospitalized patients requiring urinary catheters, how does the use of a silver-alloy coated catheter compared to a standard catheter affect the incidence of CAUTIs over a hospital stay?

- Inadequate Patient Education on Medication Management

Clinical Problem: Patients frequently return (15% within 30 days of initial discharge) to the hospital due to improper medication management at home.

Potential Clinical Question: In patients discharged from the hospital, how does a comprehensive medication education program compared to standard discharge instructions affect medication adherence and readmission rates within 30 days?

- Insufficient Management of Hypertension in Outpatient Settings

Clinical Problem: 75% of patients in an outpatient clinic have poorly controlled blood pressure despite being on antihypertensive medications.

Potential Clinical Question: In adult patients with hypertension, how does the addition of a weekly nurse-led hypertension education and follow-up program compared to usual care affect blood pressure control over six months?

- High Levels of Nurse Burnout in Intensive Care Units (ICUs)

Clinical Problem: Increased reports of burnout and job dissatisfaction among ICU nurses.

Potential Clinical Question: In ICU nurses, how does the implementation of a resilience training program compared to no intervention affect levels of burnout and job satisfaction over six months?

Developing the Components of the Research/Clinical Question

A thoughtful development of a well-structured research or clinical question is important because the question drives the strategies that you will use to search for the published evidence. The question needs to be very specific, non-ambiguous, and measurable in order to find the relevant evidence needed for a literature review leading up to a study, and also to increase the likelihood that you will find what you are looking for.

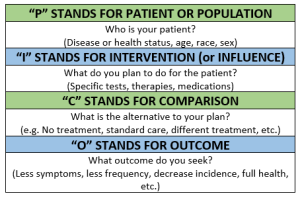

In developing your research or clinical question, there is a helpful format to utilize to establish the key component. The PICO(T) framework is a valuable tool for developing research questions, especially in clinical research. This format includes the Patient/Population, Intervention/Influence/Exposure, Comparison, Outcome (PICO), and sometimes Time (PICOT) (Richardson, Wilson, Nishikawa, & Hayward, 1995).

Let’s dive into each component to better understand:

P: Patient, population, or problem: We want to describe the patient, the population, or the problem. Get specific. We will want to know exactly who we are wanting to know about. Consider age, gender, setting of the patient (e.g. postoperative), and/or symptoms.

I: Intervention: The intervention is the action or, in other words, the treatment, process of care, education given, or assessment approaches. We will come back to this in more depth, but for now remember that the intervention is also called the “Independent Variable”.

C: Comparison: Here we are comparing with other interventions. A comparison can be standard of care that already exists, current practice, an opposite intervention/action, or a different intervention/action.

O: Outcome: What is that that we are looking at for a result or consequence of the intervention? The outcome needs to have a metric for actually measuring results. The outcome can include quality of life, patient satisfaction, cost impacts, or treatment results. The outcome is also called the “Dependent Variable”.

T: Time: What timeframe are we studying? We will intervene for 6 months? Five years? This is often a component of the research question that does not need to be included.

The PICO question is a critical aspect of the EBP project to guide the problem identification and create components that can be used to shape the literature search.

Example Using PICO(T):

Research Problem: There are high readmission rates among older adults with multiple chronic conditions.

Research Question: In older adults with multiple chronic conditions (P), does a structured discharge planning process (I) compared to standard discharge procedures (C) reduce the rate of hospital readmissions (O) within 30 days post-discharge (T)?

Let’s watch an informative YouTube video, “PICO: A Model for Evidence-Based Research”:

“PICO: A Model for Evidence Based Research” by Binghamton University Libraries. Licensed CCY BY.

Great! Okay, let’s move on and discuss the various types of PICOs.

Critical Reflection on the Research Problem

Developing a research problem is not just about identifying a gap in knowledge – it is about critically reflecting on the significance of the problem. Ask yourself:

- Why is this problem important to nursing practice?

- What are the potential implications of this research for patient care?

- Is this problem grounded in current literature, or does it reflect a new or emerging concern?

Ponder This

How does your identified research problem align with the broader goals of improving patient outcomes and advancing the nursing profession?

Types of PICOT Questions

Before we start developing our clinical question, let’s go over the various types of PICOs and the clinical question that can result from the components. There are various types of PICOs but we are concerned with the therapy/treatment/intervention format of PICO for our EBP posters.

Let’s take a look at the various types of PICOs:

|

Type of Question |

PICO Template |

|

Therapy/Intervention/Treatment (We will use this type for our EBP Posters) |

In _________ (Population), what is the effect of ___________ (Intervention) in comparison to ___________(Comparison) on __________ (Outcome)? Or Does _________ (Intervention) compared to __________ (Comparison) decrease/increase ______________ (Outcome) in ____________ (Population)?

|

|

Diagnosis/Assessment |

For _________ (Population), does __________ (Identifying tool/procedure) yield more accurate or more appropriate diagnostic/assessment information than __________ (Comparative tool/procedure) about __________ (Outcome)?

|

|

Prognosis |

For ______ (Population), does _______ (Exposure to disease or condition), relative to _______ (Comparative disease or condition) increase the risk of ________ (Outcome)?

|

|

Etiology/Harm |

Does (Influence, exposure, or characteristic) increase the risk of ________ (Outcome) compared to ________ (Comparative influence, exposure, or condition) in ________ (Population)?

|

|

Description (Prevalence/Incidence) |

These questions vary from the typical PICO in that explicit comparisons are not typical (except to compare population). In ______ (Population), how prevalent is ________ (Outcome)?

|

|

Meaning or Process |

Explicit comparisons are not typical in these types of questions. These are qualitative questions and are used to elicit narrative, subjective responses. What is it like for ________ (Population) to experience _________ (situation, condition, circumstance)?

|

These types of PICOT questions help in designing focused and meaningful research or literature searches that can directly impact clinical practice and patient care. The purpose of a PICOT question is multifaceted, serving as a critical tool in both research and literature searching:

Guiding Research: A PICOT question helps researchers clearly define the scope and focus of a study. By specifying the patient population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and timeframe, the PICOT question ensures that the research is systematic, focused, and relevant to clinical practice.

Literature Searching: PICOT questions are also essential for conducting efficient and targeted literature searches. By breaking down the research question into specific components, a PICOT question allows researchers to identify the most relevant studies, interventions, and outcomes in the existing literature, helping to build a solid evidence base for clinical decisions or further research.

In essence, PICOT questions provide a structured framework that enhances the clarity, relevance, and efficiency of both research design and evidence-based practice. Once you have your pertinent clinical question, you can use the components to begin your search in published literature for articles that help to answer your question or as a foundational literature review for your future research study.

The first step in developing a research or clinical practice question is developing your PICO. Well, we’ve done that above. You will select each component of your PICO and then turn that into your question. Making the EBP question as specific as possible really helps to identify specific terms and narrow the search, which will result in reducing the time it times searching for relevant evidence.

Once you have your pertinent clinical question, you will use the components to begin your search in published literature for articles that help to answer your question. In class, we will practice with various situations to develop PICOs and clinical questions.

![]() Hot Tip! When reading research articles, you will not see a “PICO” listed. You may see a research question, but that is rare as well. The research/clinical question is in the “background” planning phases of research projects. Meaning, the eventual hypothesis is developed from the research question and/or statement of purpose after a literature review is performed to determine what evidence already exists and establishing the research problem.

Hot Tip! When reading research articles, you will not see a “PICO” listed. You may see a research question, but that is rare as well. The research/clinical question is in the “background” planning phases of research projects. Meaning, the eventual hypothesis is developed from the research question and/or statement of purpose after a literature review is performed to determine what evidence already exists and establishing the research problem.

![]() Hot Tip! Many people assume they know the solution to their identified problems, but for evidence-based practice, it is important to realize that there may be more than one solution to a problem. Therefore, taking the time to rework your question so that it doesn’t contain a solution within it is important. For example: “Does adding more nurses per shift reduce nursing burnout?” might better be stated “What are ways to reduce nursing burnout?” because it does not presuppose a solution to the practice problem you have identified.

Hot Tip! Many people assume they know the solution to their identified problems, but for evidence-based practice, it is important to realize that there may be more than one solution to a problem. Therefore, taking the time to rework your question so that it doesn’t contain a solution within it is important. For example: “Does adding more nurses per shift reduce nursing burnout?” might better be stated “What are ways to reduce nursing burnout?” because it does not presuppose a solution to the practice problem you have identified.

Practical Application: Developing Your Own Research Problem

As you progress in your studies and practice, you’ll likely encounter various clinical scenarios that spark your curiosity. Use these experiences as opportunities to identify potential research problems.

Activity: Reflect on your recent clinical rotations or patient interactions. Identify one issue or challenge that you found particularly concerning or interesting. Write down the problem, then formulate it into a research question using the PICO(T) framework.

Ethical Dilemma Example: If you notice a recurring issue with patient consent in your practice, consider the ethical implications of investigating this problem. How might your findings influence consent procedures, and what ethical responsibilities must you uphold in conducting such research?

Conclusion

Developing a research problem is a critical step in the research process and a foundational skill for engaging with evidence-based practice. By identifying relevant, ethically sound research problems and framing them into clear, researchable questions, you contribute to improving patient care and advancing the nursing profession.

Statements of Purpose

Many research articles have the researcher’s statement of purpose for their research project. This helps to identify what the overarching direction of inquiry may be. In the realm of research, a statement of purpose is a crucial component that guides the entire study. It succinctly outlines the intent of the research, providing a clear direction for what the study aims to achieve. A statement of purpose summarizes the study’s overarching goal (Polit & Beck, 2021).

Often referred to as the research purpose, aim, or goal, this statement serves as the foundation upon which all other aspects of the research are built, including the research questions, methodology, and analysis. The statement of purpose in a research study explicitly states what the researcher intends to accomplish. It identifies the specific focus of the study, the key variables or concepts being investigated, and the overall objective of the research. Important to note is that a statement of purpose is not the same as a hypothesis or a research/clinical question. A hypothesis states what the researcher is predicting the outcome and a research question guides us to utilize EBP, while a statement of purpose is the study’s goal.

You do not need a statement of purpose/aim/goal/objective for your EBP poster. However, knowing what a statement of purpose is will help you when appraising articles to help answer your clinical question.

![]() Knowledge to application link. This statement of purpose identifies the intervention (I) of interest, as well as the outcome (O) that was being measured.

Knowledge to application link. This statement of purpose identifies the intervention (I) of interest, as well as the outcome (O) that was being measured.

The following statement of purpose was written as an aim. The population (P) was identified as patients with HF, the interventions (I) included physical activity/exercise, and the outcomes (O) included pain, depression, total activity time, and sitting time as correlated with the interventions.

In the articles above, the authors made it easy and included their statements of purpose within the abstract at the beginning of the article. Most articles do not feature this ease, and you will need to read the introduction or methodology section of the article to find the statement of purpose.

In qualitative studies, the statement of purpose usually indicates the nature of the inquiry, the key concept, the key phenomenon, and the population.

The Role of a Statement of Purpose

The statement of purpose is not merely a formal requirement; it plays several critical roles in the research process, including:

- Guiding the Research Process: It provides a clear and focused direction for the research, ensuring that the study remains aligned with its original goals.

- Clarifying the Scope: By defining the study’s boundaries, the statement of purpose helps delineate what will and will not be addressed, preventing scope creep.

- Communicating Intent: It informs the reader (or potential stakeholders) about the specific aim of the research, making it easier to understand the relevance and significance of the study.

- Establishing the Research Framework: The purpose statement often sets the stage for the research questions and/or hypothesis, and overall study design.

Crafting a Strong Statement of Purpose

A well-crafted statement of purpose is clear, concise, and specific. It typically answers the “who,” “what,” “where,” “when,” and “why” of the study. Here are some key elements to consider:

- Population/Participants: Who or what is being studied?

- Problem/Phenomenon: What is the issue, challenge, or phenomenon being investigated?

- Context: Where and when is the study taking place?

- Objective: Why is this study being conducted, and what does it aim to accomplish?

Statement of Purpose Example 1:

“The purpose of this study is to explore the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in reducing anxiety levels among adolescents diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in urban high schools over a six-month period.”

Statement of Purpose Example 2:

“This research aims to examine the impact of nurse-led community health interventions on the management of chronic hypertension in low-income rural populations.”

In both examples, the statement of purpose clearly defines the population, the intervention or focus, the context, and the objective, providing a solid foundation for the study. In qualitative studies, the statement of purpose usually indicates the nature of the inquiry, the key concept, the key phenomenon, and the population.

Thought-Provoking Scenario: The Importance of Clarity and Specificity in a Problem Statement

Consider the following scenario: A researcher writes, “The purpose of this study is to explore healthcare.” This statement is vague and lacks the specificity to guide a meaningful study. What aspect of healthcare is being explored? Which population? What outcome is of interest?

Clarity and specificity are vital because they guide the research and ensure that future researchers can replicate, validate, and build upon the study. A well-defined statement of purpose lays the groundwork for a rigorous and credible study.

Ponder This

How might a vague or overly broad statement of purpose affect the outcome of a research study? Could it lead to ambiguous results or challenges in drawing meaningful conclusions?

Aligning the Statement of Purpose with Research Questions and Hypotheses

The statement of purpose is closely linked to the research questions and hypotheses. Once the purpose is clearly defined, the next step is to formulate research questions that are directly aligned with it. These questions will guide the data collection and analysis processes.

Example:

Purpose Statement: “The purpose of this study is to evaluate the impact of a nurse-led smoking cessation program on the smoking habits of adults in community clinics.”

Research Question: “Does participation in a nurse-led smoking cessation program reduce the number of cigarettes smoked per day among adults in community clinics after six months?”

Ponder This

How does the alignment between the statement of purpose and the research questions influence a research study’s overall coherence and integrity?

Ethical Considerations in Crafting a Purpose Statement

Ethical considerations are crucial when defining the purpose of a study. Researchers must ensure that their study aims are scientifically sound and ethically responsible. This includes considering the potential risks to participants, the fairness of the research design, and the broader implications of the study’s findings.

The statement of purpose is a critical element in any research study, serving as the guiding force that shapes the entire research process. It requires careful consideration, clarity, and ethical reflection to ensure that the study is both meaningful and responsible. As you progress in your research journey, remember that a strong statement of purpose is the cornerstone of effective and impactful research.

Ponder This

What ethical responsibilities do researchers have when defining the purpose of a study, particularly when vulnerable populations are involved?

In your future research endeavors, how will you ensure that your purpose statement is not only clear and specific but also ethically sound and aligned with the broader goals of advancing nursing practice?

Ethical Dilemma Example

A researcher is interested in studying the effects of a new drug on pregnant women. However, the potential risks to the unborn child are not fully known. Should the research be pursued, and if so, how should the purpose statement be crafted to reflect the ethical complexities involved?

Understanding Hypotheses in Research

In the context of research, a hypothesis (plural: hypotheses) is a specific, testable prediction about the expected outcome of a study. It is an essential component of the research process, providing a clear statement that can be tested through empirical investigation. Hypotheses are typically grounded in theory or previous research and help guide the study’s direction, shaping the research design, methodology, and data analysis.

However, in the context of evidence-based practice (EBP) for nurses, the distinction between hypotheses and research/clinical questions is essential. A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction about the relationship between variables, commonly used in quantitative research to guide experimental or observational studies (e.g., “Patients who receive mindfulness training will report lower anxiety levels than those who do not”). However, not all nursing research, especially in EBP projects, requires a hypothesis. Instead, EBP often relies on well-structured clinical questions that focus on identifying the best available evidence to inform patient care. These questions, typically framed using PICO (Patient/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome), guide literature searches and help nurses apply research findings in practice (e.g., “In elderly patients with hypertension, how does a low-sodium diet compare to medication in reducing blood pressure?”). While hypotheses are key in scientific testing, EBP projects prioritize answering clinical questions through literature synthesis, guideline evaluation, and patient-centered decision-making.

A hypothesis must be testable, meaning it can be examined through observation, experimentation, or data analysis to determine if it is true or false. Testability ensures that a hypothesis is not just an opinion or speculation but can be measured and evaluated using scientific methods. A good testable hypothesis includes clearly defined variables and can be supported or refuted by collecting and analyzing data. For example, the hypothesis “Patients who receive at least 8 hours of sleep will have lower blood pressure than those who sleep less” is testable because it involves measurable variables (sleep duration and blood pressure) and can be assessed using clinical data. If a hypothesis cannot be tested through research, it is considered unscientific and unsuitable for evidence-based practice.

For the purpose of research, a hypothesis is a tentative statement that proposes a possible explanation for a phenomenon or predicts a relationship between variables. It is formulated prior to conducting the research and is either supported or refuted based on the study’s findings. It is an educated and formulated guess as to how the intervention (independent variable) impacts the outcome (dependent variable). It is not always a cause and effect. Sometimes, there can be just a simple association or correlation.

Function and Characteristics of Hypotheses

Again, a hypothesis (plural: hypotheses) is a statement of predicted outcome. Meaning, it is an educated and formulated guess as to how the intervention (independent variable – more on that soon!) impacts the outcome (dependent variable). It is not always a cause and effect. Sometimes there can be just a simple association or correlation. We will come back to that in a few modules.

In your PICO statement, you can think of the “I” as the independent variable and the “O” as the dependent variable. Variables will begin making more sense as we go. But for now, remember this:

Independent Variable (IV): This is a measure that can be manipulated by the researcher. Perhaps it is a medication, an educational program, or a survey. The independent variable enacts change (or not) onto the independent variable.

Dependent Variable (DV): This is the result of the independent variable. This is the variable that we utilize statistical analyses to measure. For instance, if we are intervening with a blood pressure medication (our IV), then our DV would be the measurement of the actual blood pressure.

Ideally, a hypothesis results from a well-worded research question and will include the independent (IV) and dependent (DV) variables. The following is an example of this. Can you pick out the IV and DV? If you picked sexual abuse as the IV and irritable bowel syndrome as the DV, you are correct!

Research Question: “Does sexual abuse in childhood affect the development of irritable bowel syndrome in women?”

Research Hypothesis: Women (P) who were sexually abused in childhood (I) have a higher incidence of irritable bowel syndrome (O) than women who were not abused (C).

You may note in that hypothesis that there is a predicted direction of outcome. One thing leads to something.

But, why do we need a hypothesis? First, they help to promote critical thinking. Second, it gives the researcher a way to measure a relationship. Suppose we conducted a study guided only by a research question. Take the above question, for example. Without a hypothesis, the researcher is seemingly prepared to accept any result (Polit & Beck, 2021). The problem with that is that it is almost always possible to explain something superficially after the fact, even if the findings are inconclusive. A hypothesis reduces the possibility that spurious results will be misconstrued (Polit & Beck, 2021).

![]() Knowledge to application link.

Knowledge to application link.

Not all research articles will list a hypothesis. This makes it more difficult to critically appraise the results. That is not to say that the results would be invalidated, but it should ignite a spirit of further inquiry as to if the results are valid.

Types of Hypotheses

Understanding the different types of hypotheses is crucial for conducting robust research. In research, when we say “hypothesis,” we are usually referring to the alternative hypothesis (H₁ or Ha) because it represents what the researcher is trying to find evidence for. The alternative hypothesis states that there is a difference, relationship, or effect between variables, while the null hypothesis (H₀) states that there is no effect or difference. Since research is typically conducted to test for a change or relationship, the alternative hypothesis is the main focus—which is why many people simply call it “the hypothesis.” For example, if a nurse wants to study whether a new wound dressing heals wounds faster, the hypothesis would be “The new wound dressing leads to faster healing”—which is actually the alternative hypothesis because it suggests a difference. Here are the most common general types:

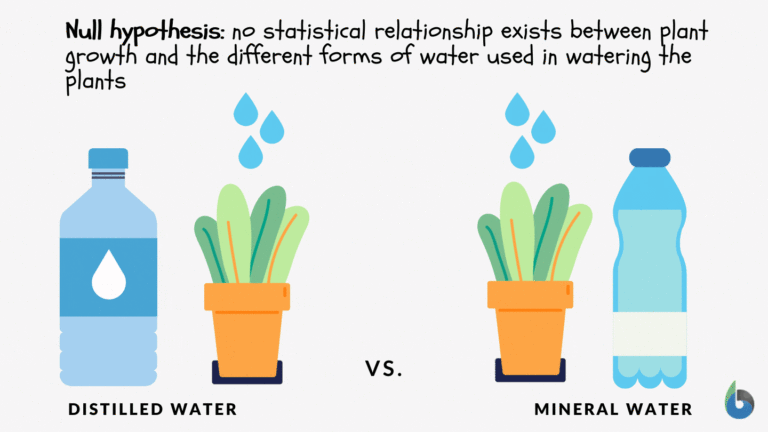

Null Hypothesis (H₀):

Purpose: The null hypothesis states that there is no effect, relationship, or difference between variables. It serves as a baseline that researchers seek to refute.

Example: “There is no significant difference in blood pressure levels between patients who receive a low-sodium diet and those who do not.”

Alternative Hypothesis (H₁ or Ha) (AKA: this is the same as the plain ol’ “hypothesis”):

Purpose: The alternative hypothesis posits that there is an effect, relationship, or difference between variables. It is what the researcher aims to support through the study.

Example: “Patients who receive a low-sodium diet will have significantly lower blood pressure levels compared to those who do not.”

Directional Hypothesis:

Purpose: A directional hypothesis specifies the direction of the expected relationship or difference between variables.

Example: “Nurse-led education programs will lead to a decrease in patient anxiety levels.”

Non-Directional Hypothesis:

Purpose: A non-directional hypothesis predicts a relationship or difference between variables but does not specify the direction.

Example: “There is a difference in anxiety levels between patients who receive nurse-led education programs and those who do not.”

Complex Hypothesis:

Purpose: A complex hypothesis predicts the relationship between multiple independent and/or dependent variables.

Example: “The implementation of a nurse-led education program and regular physical exercise will lead to lower anxiety and depression levels among patients.”

Simple Hypothesis:

Purpose: A simple hypothesis predicts the relationship between a single independent variable and a single dependent variable.

Example: “Increased hand hygiene practices reduce the incidence of hospital-acquired infections.”

An important concept to note is that a hypothesis can tick more than one box. For example, an alternative hypothesis can be a simple hypothesis, and it can be a non-directional or directional hypothesis as well. See the following table for a breakdown of more hypotheses.

Table: Types of Hypotheses

| Type of Hypothesis | Definition | Example in Nursing/Healthcare

|

| Null Hypothesis (H₀) | States that no relationship or difference exists between variables. | “There is no difference in pain levels between patients who receive acupuncture and those who do not.”

|

| Alternative Hypothesis (H₁ or Ha) | States that a relationship or difference exists between variables. | “Patients who receive acupuncture will report lower pain levels than those who do not receive acupuncture.” |

| Directional Hypothesis | Predicts the direction of the relationship between variables. | “Nurses who work night shifts will have higher levels of fatigue than hose who work day shifts.”

|

| Non-Directional Hypothesis | Predicts that a relationship exists but does not specific the direction. | “There will be a difference in fatigue levels between nurses who work night shifts and those who work day shifts.” |

| Simple Hypothesis | Involves a single independent and dependent variable. | “Increased hand hygiene reduces hospital-acquired infections.” |

| Complex Hypothesis | Involves two or more independent and dependent variables. | “Increased hand hygiene and improved sanitation reduce hospital-acquired infections and patient recovery time.” |

| Associative Hypothesis | Suggests that variables are related but do not imply cause and effect. | “There is a relationship between nurse-patient ratios and patient satisfaction scores.” |

| Causal Hypothesis | Suggests that one variable directly influences another (cause and effect). | “Increased nurse staffing levels will lead to lower patient mortality rates.” |

| Statistical Hypothesis | A hypothesis tested using statistical analysis to determine significance. | “There is a statistically significant reduction in hospital readmission rates after implementing a new discharge planning protocol.” |

| Empirical Hypothesis | Based on observation and experimentation rather than theory alone. | “Patients who receive physical therapy after knee replacement surgery recover faster than those who do not.” |

| Working Hypothesis | A preliminary hypothesis that guides initial research but may be modified. | “Wearing compression socks may reduce swelling in post-operative patients, but further research is needed to confirm.” |

| Logical Hypothesis | Based on logical reasoning rather than direct experimental evidence. | “If stress contributes to high blood pressure, then relaxation techniques should help lower blood pressure.” |

| Nullifiable Hypothesis | A hypothesis than can be said to be false through evidence. | “If there is no difference in patient satisfaction between telehealth and in-person visits, then survey results should show no significant variation.” |

Crafting a Strong Hypothesis

A well-crafted hypothesis is specific, testable, and based on existing literature or theory. It should clearly state the expected relationship between variables and be formulated in a way that can be empirically tested.

- Clarity: The hypothesis should be clearly stated, leaving no ambiguity about the expected outcome.

- Testability: The hypothesis must be formulated so that it can be tested through observation, experimentation, or analysis.

- Specificity: The hypothesis should be specific enough to guide the research design and data collection process.

For example, “Regular physical activity reduces the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in adults aged 40-60.” This hypothesis is clear, testable, and specific, making it an effective guide for research.

It is important to remember that the types of hypotheses can tick more than one box. For example, a hypothesis can be complex and directional, or perhaps simple and non-directional.

Ethical Considerations in Hypothesis Development

Ethical considerations are critical when formulating hypotheses. Researchers must ensure that their hypotheses do not lead to harm, bias, or exploitation. This includes considering the potential impact of the research on participants, particularly vulnerable populations, and ensuring that the research is conducted with integrity.

Ponder This

How does the specificity of a hypothesis impact the research process, including the design, data collection, and interpretation of results? What challenges might arise if a hypothesis is too broad or vague?

Ethical Dilemma Example

A researcher hypothesizes that a new drug will significantly improve outcomes for patients with a terminal illness. However, the drug has not been fully tested for safety, and there is a risk of severe side effects. The ethical dilemma here is whether to proceed with the research knowing the potential risks.

Testing and Refining Hypotheses

Once a hypothesis is developed, it must be tested through research. The results will either support or refute the hypothesis, leading to conclusions about the relationship between variables. If the hypothesis is not supported, researchers may refine it based on the findings and conduct further studies.

Example:

Hypothesis: “A nurse-led intervention will reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients.”

Testing: The hypothesis is tested through a controlled study where some patients receive the intervention and others do not. If the incidence of pressure ulcers is significantly lower in the intervention group, the hypothesis is supported.

Hypotheses are a foundational element of the research process, providing a clear, testable prediction that guides the study from start to finish. By understanding the different types of hypotheses and the ethical considerations involved, you can craft strong, meaningful hypotheses that contribute to the advancement of nursing knowledge and practice.

![]() EBP Poster Application! Continue to work on the Introduction section of your poster. Again, going back to the beginning of this module, ask the following:

EBP Poster Application! Continue to work on the Introduction section of your poster. Again, going back to the beginning of this module, ask the following:

- Is there evidence that the current treatment works?

- Does the current practice help the patient?

- Why are we doing the current practice?

- Should we be doing the current practice this way?

- Is there a way to do this current practice more efficiently?

- Is there a more cost-effective method to do this practice?

And then, further develop the problem and background through finding existing literature to help answer the following questions:

- Problem identification: What is wrong with the current situation or action?

- Background: What is the nature of the problem or the context of the situation? (this helps to establish the why)

- Scope of the problem: How many people are affected? Is this a small problem? Big problem? Potential to grow quickly to a large problem? Has been increasing/decreasing recently?

- Consequences of the problem: If we do nothing or leave as the status quo, what is the cost of not fixing the issue?

- Knowledge gaps: What information about the problem is lacking? We need to know what we do not know.

- Proposed solution: How will the information or evidence contribute to the solution of the problem?

With the previous example of pain in the pediatric population, here is an example of an Introduction section from a past student poster:

In summary, we explored the foundational steps in developing a research study, starting with the critical process of identifying and articulating clinical or research problems that are significant to nursing practice. By understanding how to construct well-structured clinical questions, particularly through the PICOT framework, you can guide evidence-based practice and address specific nursing issues effectively. The chapter also emphasized the importance of clearly defined statements of purpose, aligned research questions, and hypotheses in structuring a study. Crafting a well-defined hypothesis and evaluating the relevance of clinical questions are key skills that enhance the quality and impact of nursing research. By analyzing real-world examples of clinical questions, purpose statements, and hypotheses, you are now equipped to approach research and clinical inquiries with a more strategic and evidence-based mindset, paving the way for meaningful contributions to nursing practice.

Summary Points

Every research study begins with a problem—a gap, concern, or difficulty identified in clinical practice, literature, or observed patient outcomes.

A research problem must be researchable—able to be studied through data collection and analysis; moral or ethical questions are not researchable in themselves, though opinions about them can be studied.

The problem statement should define the issue, explain its context, outline its scope, identify consequences, and highlight knowledge gaps.

Research problems often emerge from clinical practice through repeated observations of inefficiencies, adverse events, or variations in patient outcomes.

Two main sources of problems are problem-focused triggers (e.g., adverse events, quality concerns) and knowledge-focused triggers (e.g., new evidence, updated guidelines).

The first step of EBP is Ask—formulating a clear, answerable clinical question to guide the search for evidence.

The PICO(T) framework helps structure clinical questions by identifying the Patient/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and (sometimes) Time.

Different types of PICO questions include therapy/intervention, diagnosis, prognosis, etiology/harm, description, and meaning/process.

Well-structured PICOs enhance literature searches by making the question specific, measurable, and easier to match to research evidence.

Statements of purpose summarize the aim of a research study, specifying its focus, population, context, and intended contribution.

Purpose statements differ from research questions and hypotheses—they describe the study’s goal, not the predicted outcome.

A strong statement of purpose is clear, concise, specific, and aligned with ethical standards and clinical significance.

Hypotheses are testable predictions about the relationship between variables, often used in quantitative research.

The independent variable (IV) is the intervention or factor manipulated or observed; the dependent variable (DV) is the outcome measured.

Types of hypotheses include null (H₀), alternative (H₁), directional, non-directional, simple, complex, associative, causal, statistical, empirical, working, logical, and nullifiable.

Hypotheses help guide research design and analysis by focusing on specific, measurable relationships between variables.

A good hypothesis is clear, testable, specific, and based on literature or theory, ensuring that it can be supported or refuted with data.

Ethical considerations apply to all stages—problems, PICOs, purpose statements, and hypotheses must align with beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice.

Hypotheses are tested through research, and results either support or refute them; unsupported hypotheses may be refined for future study.

Identifying problems, formulating PICOs, defining purpose statements, and crafting hypotheses are foundational skills that guide meaningful nursing research and evidence-based practice.

![]() Critical Appraisal! Hypotheses and Research Questions:

Critical Appraisal! Hypotheses and Research Questions:

- What was the research problem? Was the problem statement easy to locate and was it clearly stated? Did the problem statement build a coherent and persuasive argument for the new study?

- Does the problem have significance for nursing?

- Was there a good fit between the research problem and the paradigm (and tradition) within which the research was conducted?

- Did the report formally present a statement of purpose, research question, and/or hypotheses? Was this information communicated clearly and concisely, and was it placed in a logical and useful location?

- Were purpose statements or research questions worded appropriately (e.g., were key concepts/variables identified and the population specified?

- If there were no formal hypotheses, was their absence justified? Were statistical tests used in analyzing the data despite the absence of stated hypotheses?

- Were hypotheses (if any) properly worded—did they state a predicted relationship between two or more variables? Were they presented as research or as null hypotheses?

Case Study: Evaluating the Impact of a Mindfulness Program on Nursing Students’ Stress Levels

Beth is a senior nursing student completing her final year of a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) program. Throughout her clinical rotations, she noticed that many of her peers, including herself, experienced high levels of stress, particularly during exams and practical assessments. The stress seemed to affect not only their academic performance but also their overall well-being.

Intrigued by the potential benefits of stress reduction techniques, Beth began exploring the use of mindfulness programs as a tool for reducing stress in nursing students. She came across several studies suggesting that mindfulness could be an effective strategy for managing stress, but the results were mixed, and there was limited research specifically focusing on nursing students.

Beth decided to conduct a research study as part of her final year project to investigate whether a structured mindfulness program could significantly reduce stress levels among her peers.

Research Problem: The high levels of stress experienced by nursing students during their academic and clinical training can negatively impact their performance and well-being. However, there is limited research on the effectiveness of mindfulness programs in reducing stress, specifically among nursing students.

Hypothesis: Beth hypothesized that “A structured eight-week mindfulness program will significantly reduce perceived stress levels among nursing students compared to those who do not participate in the program.”

Study Design: Beth designed a quasi-experimental study with two groups of nursing students: one group would participate in an eight-week mindfulness program, while the other group would serve as a control and continue with their usual activities. She used a validated perceived stress scale (PSS) to measure stress levels before and after the intervention.

Implementation: The mindfulness program consisted of weekly sessions led by a certified mindfulness instructor. Each session included guided meditation, breathing exercises, and discussions on incorporating mindfulness into daily life. Participants were also encouraged to practice mindfulness exercises at home. Beth recruited 50 nursing students for the study, with 25 in the mindfulness group and 25 in the control group. She ensured that both groups were similar in terms of demographics and baseline stress levels.

Outcomes: At the end of the eight weeks, Beth analyzed the data to compare the stress levels between the two groups. The results showed that the students who participated in the mindfulness program had a statistically significant reduction in perceived stress levels compared to the control group. Many participants in the mindfulness group also reported improved focus and a greater sense of calm during exams and clinical rotations.

Conclusion: Beth’s study supported her hypothesis that a structured mindfulness program could effectively reduce stress levels among nursing students. The findings suggest that incorporating mindfulness into nursing education could be a valuable tool for promoting student well-being and enhancing academic performance. Beth’s research not only contributed to the existing literature but also provided practical insights for nursing programs looking to support their students’ mental health. The study’s success also inspired Beth to advocate for integrating mindfulness programs into the nursing curriculum, recognizing the potential long-term benefits for both students and the profession as a whole.

Ponder This

As you develop hypotheses in your research, or critique published studies, how will you ensure that they are scientifically rigorous, ethically sound, and aligned with the values of nursing and patient care?

References & Attribution

“Green check mark” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

“Light bulb doodle” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

“Magnifying glass” by rawpixel licensed CC0

“Orange flame” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2000). Changing concepts of sudden infant death syndrome: Implications for infant sleeping environment and sleep position. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Bristol, J. (2021). Early ambulation in hip replacement patients regarding length of hospital stay. Journal of Orthopedics and Orthopedic Surgery, 2(2), 30-34.

Chen, P., Nunez-Smith, M., Bernheim, S… (2010). Professional experiences of international medical graduates practicing primary care in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(9), 947-53.

Dearholt, S.L., & Dang, D. (2012). Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice: Model and guidelines (2nd Ed.). Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International.

Gan, T. (2017). Poorly controlled postoperative pain: Prevalence, consequences, and prevention. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 2287-2298.

Genc, A., Can, G., Aydiner, A. (2012). The efficiency of the acupressure in prevention of the chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Support Care Cancer, 21, 253-261.

Haedtke, C., Smith, M., VanBuren, J., Kein, D., Turvey, C. (2017). The relationships among pain, depression, and physical activity in patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 32(5), E21-E25.

McGaghie, W.C., Bordage, G., & Shea, J.A. (2001). Problem statement, conceptual framework, and research question. Academic Medicine, 76(9), 923-924.

Medical College of Wisconsin Libraries. (2024). Evidence-Based Practice: Overview. https://mcw.libguides.com/evidencebasedpractice

Pankong, O., Pothiban, L., Sucamvang, K., Khampolsiri, T. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of enhancing positive aspects of caregiving in Thai dementia caregivers for dementia. Pacific Rim Internal Journal of Nursing Res, 22(2), 131-143.

Polit, D. & Beck, C. (2021). Lippincott CoursePoint Enhanced for Polit’s Essentials of Nursing Research (10th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health.

Rawal, N. (2016). Current issues in postoperative pain management. European Journal of Anaesthesiology, 33, 160-171.

Richardson, W.W., Wilson, M.C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R.S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. American College of Physicians, 123(3), A12-A13.

Titler, M. G., Kleiber, C., Steelman, V.J. Rakel, B. A. Budreau, G., Everett,…Goode, C.J. (2001). The Iowa model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 13(4), 497-509.