The Third Step: Appraise – Reading & Appraising Research Articles

You are well on your way! Now that you understand how to perform a rigorous search for literature, let’s learn about the sections of a research article so that you can make some sense out of what you’re reading. Remember, you are not expected to be an expert in understanding everything in a research article, but by the end of this course you are to understand some of the basic critical appraisal components so that you can be a knowledgeable consumer of research (and also be reading for 3rd and 4th semester!).

Content includes:

- Importance of Research Appraisal in Evidence-Based Practice (EBP)

- Elements of a Research Critique

- Understanding the Structure of a Research Article (IMRAD Format)

- Critical Appraisal Frameworks and Tools

- Assessing Validity, Reliability, and Bias in Research

- Interpreting Statistical Findings in Research Articles

- Critiquing Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research

- Critiquing Secondary Research

- Common Errors and Red Flags in Research Studies

- Ethical Considerations in Research Appraisal

Objectives:

- Explain the importance of research appraisal in evidence-based nursing practice.

- Explain the elements of a research critique.

- Identify the key components of a research article and their functions.

- Utilize critical appraisal frameworks and tools to systematically evaluate research studies.

- Assess the strength, validity, and reliability of evidence presented in research articles.

- Recognize common biases and methodological flaws in research.

- Interpret statistical findings within research articles and their implications for practice.

- Compare and contrast the appraisal of qualitative and quantitative research.

- Identify ethical considerations related to research appraisal and dissemination.

Key Terms:

Appraisal of Evidence – A systematic process of evaluating research studies to determine their quality, credibility, and applicability to practice.

Bias – Systematic errors in research that can distort findings, often introduced through study design, sample selection, or researcher influence.

Critical Appraisal – The process of carefully and systematically examining research to assess its trustworthiness, value, and relevance.

Evidence Hierarchy – A ranking system used to evaluate the strength and quality of research evidence in guiding clinical decisions.

IMRAD Format – The typical structure of a research article: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion.

Qualitative Research Critique – The systematic evaluation of non-numeric, descriptive studies to assess their rigor, trustworthiness, and applicability.

Quantitative Research Critique – The systematic evaluation of numeric, data-driven studies to assess their validity, reliability, and generalizability.

Reliability – The consistency and stability of the measurement instruments and research findings over time.

Statistical Significance – A measure indicating whether the results of a study are likely due to chance or represent a true effect.

Validity – The extent to which a study accurately reflects or assesses the concept being investigated.

Introduction

In evidence-based nursing practice, critically appraising research articles is essential. Nurses must evaluate research studies for their credibility, relevance, and applicability before integrating findings into practice. This chapter provides a structured approach to reading and critiquing research articles by introducing key concepts, frameworks, and evaluation techniques.

A Review of the Peer-Review Process

Submitted papers or articles are often subjected to a peer review by the journal. Peer review is designed to assess the validity, quality and often the originality of articles for publication. Its ultimate purpose is to maintain the integrity of science by filtering out invalid or poor-quality articles. When the article is submitted, it will be reviewed by two or more peer reviewers who are experts in the same field. Most of the time these reviews are blinded, meaning the author of the article does not know who the reviewers are, and the reviewers do not know who the author is. As a consumer of research, you have some assurance that the journal articles are of quality and have been vetted. However, to note, is that this process is not the end-all-be-all. Meaning, just because it has been peer reviewed and published, it does not remove the need to critically appraise a publication.

Important of Research Appraisal in Evidence-Based Practice (EBP)

Research appraisal ensures clinical decisions are based on high-quality, reliable, and relevant evidence, ultimately improving patient outcomes. Without proper appraisal, flawed or biased research could misguide clinical practice, resulting in ineffective or harmful interventions. Appraising research allows nurses to discern credible studies from those with methodological weaknesses, ensuring that the best available evidence informs decision-making. This section highlights the essential role of research appraisal in evidence-based practice (EBP), emphasizing its impact on patient safety, healthcare policy, and the advancement of nursing interventions.

A nurse working in a hospital setting may encounter conflicting recommendations for managing post-operative pain. One study may suggest using a multimodal pain management approach, while another recommends a single medication. By critically appraising both studies, the nurse evaluates their methodologies, sample sizes, and outcomes to determine which approach provides patients with the most effective and safest pain relief.

Practical Application: Patient Safety Protocol

A healthcare organization is considering the implementation of a new patient safety protocol based on recent research findings. The nursing leadership team must assess the study’s credibility before recommending changes. The study claims a significant reduction in medication errors; however, upon appraisal, the team notices the study’s small sample size and potential conflicts of interest. This realization prompts further investigation into additional supporting research before policy adoption.

In addition to affecting direct patient care, research appraisal influences broader healthcare policies. Regulatory agencies and hospital administrators rely on well-conducted research to formulate guidelines and protocols. For instance, national vaccination programs depend on rigorously appraised studies demonstrating efficacy and safety before being recommended to the public.

Gray et al. (2020) states that in the 1940s-1950s, research appraisals in nursing research were less than rigorous. Fast forward to the 1990s, and critical appraisals have become much more rigorous with the help of critical appraisal tools. Not all published research is equal. In fact, some of it is not scientifically sound. For this reason, nurses are charged with having critical appraisal skills. Polit and Beck (2020) state that by being able to scrutinize and critically review a study, nurses can make valuable contributions to the body of nursing knowledge.

By mastering research appraisal, nurses enhance their ability to provide evidence-based care, advocate for best practices, and contribute to improved patient outcomes. This section establishes the foundation for understanding how to systematically evaluate research studies to make informed clinical decisions.

Table: Key Aspects of Research Appraisal

| Aspect | Importance |

| Study Design | Determines the strength and applicability of findings. |

| Sample Size | Affects the reliability and generalizability of results. |

| Data Collection | Ensures accuracy and minimizes bias. |

| Statistical Analysis | Confirms validity of conclusions. |

| Ethical Considerations | Protects participant rights and integrity of research. |

Elements of a Research Critique

A research critique is a systematic evaluation of a study’s strengths, weaknesses, and overall contribution to nursing knowledge and evidence-based practice. It involves a detailed examination of various components of a research study to determine its validity, reliability, and applicability. Below are the essential elements of a research critique:

- Study Purpose

The study purpose should be clearly stated and aligned with the research problem. A well-defined purpose provides direction for the study and helps readers determine its relevance to nursing practice. When critiquing the study purpose, consider:

- Is the purpose explicitly stated?

- Does the purpose align with the identified research problem?

- Is the significance of the study adequately justified?

- How does the study contribute to nursing knowledge or patient care?

- Research Design

The research design outlines the overall structure of the study and determines the methodology used to collect and analyze data. When critiquing the research design, consider:

- Is the research design appropriate for answering the research question?

- Is the study experimental, non-experimental, qualitative, or quantitative?

- Does the design allow for control of variables and potential biases?

- Are any threats to internal or external validity addressed?

- Literature Review

A thorough literature review provides background information, justifies the need for the study, and situates the research within existing knowledge. A critique of the literature review should address:

- Is the literature review comprehensive and up to date?

- Are key theories and previous studies relevant to the research topic included?

- Is there a clear connection between the literature review and the study purpose?

- Are gaps in knowledge identified?

- Hypothesis or Research Question

A study may include a hypothesis (in quantitative research) or a research question (in both qualitative and quantitative research). When critiquing this component, consider:

- Is the hypothesis or research question clearly stated?

- Does it align with the study purpose and research design?

- If a hypothesis is present, is it directional or non-directional, null or alternative?

- Is the hypothesis or research question testable or answerable with the chosen methodology?

- Study Sample

The sample refers to the group of participants selected for the study. A strong critique of the study sample should assess:

- Is the sample size adequate to produce meaningful results?

- Are inclusion and exclusion criteria clearly defined?

- Was probability or nonprobability sampling used, and is it appropriate for the study?

- Are potential biases in sample selection addressed?

- How generalizable are the findings based on the sample used?

- Data Collection

The method of data collection should be appropriate for answering the research question and ensuring accurate measurement. When critiquing data collection, consider:

- Are data collection methods clearly described?

- Were instruments or tools used to collect data valid and reliable?

- Is the data collection process standardized?

- Were ethical considerations, such as informed consent and confidentiality, addressed?

- Study Results

The results section presents the findings of the study in a clear and logical manner. When critiquing study results, examine:

- Are the results clearly reported and easy to interpret?

- Are statistical analyses appropriately conducted and explained?

- If qualitative, are themes and patterns adequately described?

- Do the results answer the research question or test the hypothesis?

- Study Recommendations

The recommendations section provides implications for practice, future research, or policy changes. A critique should consider:

- Are the recommendations logical and based on the findings?

- Do they align with the study’s strengths and limitations?

- Are suggestions for future research identified?

- How can the findings contribute to nursing practice or healthcare policy?

Understanding the Structure of a Research Article (IMRAD Format)

Journal articles follow a similar format regardless of which journal they are published in. There may be some small changes, but for the most part they follow the IMRAD format:

- Title and abstract

- Introduction

- Methods

- Results

- (and) Discussion

- References

Title and Abstract: The title presents a starting point in determining whether or not the article has potential to be included in an EBP review. Ideally, the title should be informative. It should also help the reader to understand what type of study is being reported. But don’t rely solely on a title! They can be misleading. Be careful that it is not just an informative article or opinion piece.

In qualitative articles, the title will normally include the central phenomenon and group under investigation. In quantitative articles, the title communicates the key variables and the population (PIO components). Again, these are the usual title components, but not always.

![]() Knowledge to application link.

Knowledge to application link.

Quantitative article title:

(Haedtke et al, 2017)

Qualitative article title:

(Chen et al., 2010)

The abstract will be at the start of the paper. It contains a brief description of the study. Abstract components include a brief introduction, aims/goals, methods/methodology, and the results and conclusions. Some abstracts also include the research question, hypothesis, and implications to practice.

This is located after the title it is usually set apart by the use of a box, shading, or italics. The abstract is a great starting point in quickly filtering articles that may be of use. It’s a nice thumbnail sketch. But, caution! Don’t forgo reading the article! The abstract should serve as a screening device only.

Introduction: The introduction is the start of the article after the abstract. It normally does not contain a heading. The introduction contains the author’s literature review.

When critically appraising an article, if the abstract appears relevant, then move onto reading the introduction. The introduction contains the background as well as a problem statement that tells the reader why the study was eventually conducted. It is presented within the context of a current literature review, and it should contain the knowledge gap between what is known and what the study seeks to find (AKA: what is not known yet). It usually (but not always) contains a statement of expected results or hypothesis as well. The literature review section of an article is a summary or analysis of all the published research for prior findings in research and other information that the author read before doing his/her own research. This section is part of the introduction (or in a section called Background). This is the “Review of Literature” (ROL) that the research/author conducted before beginning his/her own study. The articles and information in the Introduction will be cited. It is important to review those citations (found in the References section of an article) to make sure they are up to date and provides a state-of-the-art synthesis of current evidence on the research problem. The ROL also needs to provide a strong rationale for the new study that the researcher wants to conduct. The Introduction section of an article is very similar to your Introduction section of the EBP Poster that you are working on.

The introduction will also usually include a description of the central concepts or variables (sometimes these are in the Methods section instead); the study purpose, research questions, or hypotheses; a review of literature; theoretical/conceptual framework, and the study significance/need for the study.

![]() Knowledge to application link.

Knowledge to application link.

Quantitative introduction:

Qualitative introduction:

![]() Critical Appraisal! Introduction (Literature Review) Section:

Critical Appraisal! Introduction (Literature Review) Section:

- Does the review seem thorough and up-to-date? Did it include major studies on the topic? Did it include recent research?

- Did the review rely mainly on research reports, using primary sources?

- Did the review critically appraise and compare key studies? Did it identify important gaps in the literature?

- Was the review well organized? Is the development of ideas clear?

- Did the review use appropriate language, suggesting the tentativeness of prior findings? Is the review objective?

- If the review was in the introduction for a new study, did the review support the need for the study?

- If the review was designed to summarize evidence for clinical practice, did it draw appropriate conclusions about practice implications?

Methods: This section describes how a study is conducted. In quantitative studies, the methods section contains the research design, sampling plan, methods for measuring variables and collecting data, the study procedures, participant protection, and analytic methods and procedures. In qualitative studies, the methods section discusses many of the same issues as quantitative researchers do but with different emphases. More information is provided about the research setting in a more organically focused fashion, in the context of the study.

![]() Knowledge to application link.

Knowledge to application link.

Quantitative Methods:

Qualitative Methods:

Results: The results section contains the findings of the study. This section is very objective without any researcher interpretation. These are the raw findings from data. The statistical tests will be names, the value of the statistics will be listed, statistical significance will be listed, and the level of significance is listed. The level of significance, which we will come back to later in the modules, is an index of how probably it is that the findings were not just simply due to chance and is listed as the p value. In qualitative studies, the results are a bit different. They are organized according to major themes (thematic results) and most often include raw data as quotes from the study participants.

Figures and tables are usually presented – some inferential and some descriptive. Also look to see whether the results report statistical versus clinical significance. You might have to look up unfamiliarly terminology regarding statistical tests.

![]() Knowledge to application link.

Knowledge to application link.

Quantitative results:

Qualitative results:

Discussion: This section should be tied back to the introduction. The study findings should be discussed and meaning given to the raw data results. The weaknesses/limitations and bias should be reported. Any limitations and bias should be discussed in this section as well. If there is clinical significance, this will usually be discussed.

![]() Hot Tip! Caution! As a reader, you should be aware that some writing may use language to sway the reader. Researchers can overstate their findings or use an assertive sentence in a way that makes their statement of findings sound like a well-established fact (Graham, 1957). Critically view expressions similar to, “It is generally believed that….” Ask yourself, “Who believes that? Why? What evidence supports that belief? Is there any evidence to support that belief?” Critically think! Never assume.

Hot Tip! Caution! As a reader, you should be aware that some writing may use language to sway the reader. Researchers can overstate their findings or use an assertive sentence in a way that makes their statement of findings sound like a well-established fact (Graham, 1957). Critically view expressions similar to, “It is generally believed that….” Ask yourself, “Who believes that? Why? What evidence supports that belief? Is there any evidence to support that belief?” Critically think! Never assume.

Critical Appraisal Frameworks and Tools

Appraisal tools provide structured methods to systematically evaluate research articles. These frameworks help determine the validity, reliability, and applicability of research findings to nursing practice. Below are some of the commonly used critical appraisal tools and their applications:

- CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme): Guides evaluation of qualitative and quantitative studies. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute) Checklists: Provides standardized criteria for assessing research quality. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation): Assesses the strength of evidence and recommendations. https://training.cochrane.org/grade-approach

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses): Evaluates systematic reviews. https://www.prisma-statement.org/

Table: Comparison of Critical Appraisal Tools

| Tool | Best For | Key Features |

| CASP | Qualitative and Quantitative Research | Structured checklists, bias assessment |

| JBI | Various study designs | Checklists tailored to study types |

| GRADE | Evaluating strength of evidence | Ranks evidence quality |

| PRISMA | Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses | Ensures comprehensive reporting |

| Cochrane Risk of Bias | RCTs | Assesses bias in experimental studies |

| AMSTAR | Systematic Reviews | Evaluates methodological quality |

| STROBE | Observational Studies | Enhances reporting transparency |

Assessing Validity, Reliability, and Bias in Research

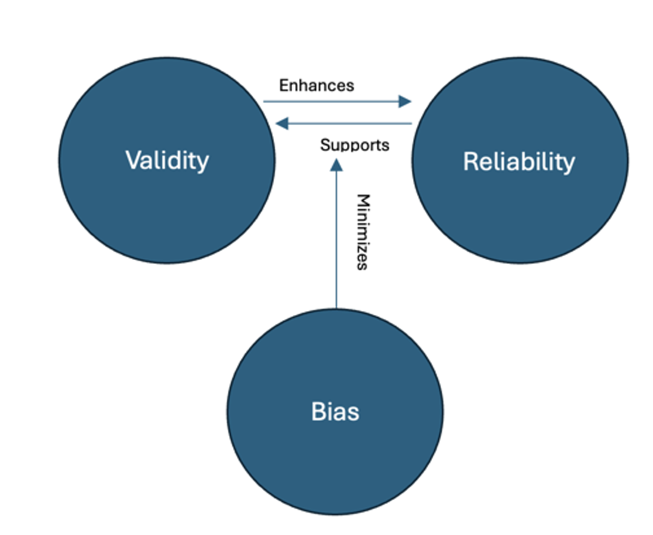

Assessing validity, reliability, and bias in research is essential to ensuring the credibility and applicability of findings in nursing and healthcare. These three concepts work together to determine whether a study accurately represents reality and can be trusted to inform evidence-based practice. Researchers must carefully design and evaluate their studies to minimize errors that could compromise the integrity of their results.

Validity

Validity refers to the degree to which a study measures what it claims to measure. It ensures that the conclusions drawn from a study accurately reflect the phenomenon under investigation. Validity is categorized into several types, including internal validity, external validity, construct validity, and criterion validity.

Internal validity assesses whether the observed changes in the dependent variable are truly due to the manipulation of the independent variable and not to extraneous factors. For example, if a study aims to determine the effect of a new medication on blood pressure, internal validity is compromised if participants alter their diet or exercise habits during the study, influencing the results. Researchers enhance internal validity by controlling confounding variables, using randomization, and employing blinding techniques.

External validity concerns the generalizability of study findings beyond the specific sample and setting. A study demonstrating that a nursing intervention improves patient adherence to medication in a controlled hospital environment may not necessarily yield the same results in a community clinic or home healthcare setting. Ensuring diverse and representative samples, as well as testing interventions in multiple settings, can improve external validity.

Construct validity evaluates whether the research truly measures the intended concept. This is particularly important in studies involving psychological or behavioral constructs such as patient satisfaction or anxiety levels. If a study uses a questionnaire to measure stress but fails to include relevant dimensions of stress, construct validity may be threatened. Researchers establish construct validity through techniques such as factor analysis and by ensuring alignment between theoretical frameworks and measurement tools.

Criterion validity examines how well one measure correlates with an established benchmark. For instance, a new pain assessment tool should yield similar results to a well-validated pain scale. If the new tool produces significantly different scores without justification, its criterion validity is questionable. Researchers assess this validity through concurrent validity (comparison with an existing tool) or predictive validity (ability to forecast future outcomes accurately).

Reliability

Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of measurement across time, observers, and instruments. A measurement is considered reliable if it produces the same results under consistent conditions. There are several types of reliability, including test-retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, and internal consistency reliability.

Test-retest reliability assesses the stability of a measurement over time. If a patient takes a depression questionnaire twice within a short period and receives vastly different scores without any major life changes, the measure lacks test-retest reliability. Researchers improve this reliability by refining measurement tools and standardizing testing conditions.

Inter-rater reliability determines the degree to which different observers produce consistent results. In nursing research, if two nurses independently assess wound healing using a specific scale, their ratings should be similar if the scale is reliable. Training observers and providing clear rating criteria enhance inter-rater reliability.

Internal consistency reliability examines how well the items in a questionnaire or scale measure the same construct. A survey assessing job satisfaction should have items that are highly correlated if they truly measure the same underlying concept. Cronbach’s alpha is commonly used to assess internal consistency, with values above 0.70 generally indicating acceptable reliability.

Bias

Bias in research arises from systematic errors that distort findings and reduce their credibility. Bias can originate from study design, data collection, or analysis and can lead to misleading conclusions. Several types of bias commonly affect nursing research, including selection bias, measurement bias, and confirmation bias.

Selection bias occurs when the study sample is not representative of the target population. For example, if a study on fall prevention strategies only includes young, physically active nurses, the findings may not be applicable to older or less mobile nurses. Random sampling and stratified sampling techniques help reduce selection bias.

Measurement bias arises when data collection methods introduce systematic errors. If blood pressure is measured using an improperly calibrated sphygmomanometer, all readings may be skewed, leading to inaccurate conclusions. Ensuring standardized procedures, using validated instruments, and training data collectors can minimize measurement bias.

Confirmation bias occurs when researchers unintentionally interpret data in a way that supports their preexisting beliefs. This can lead to overlooking contradictory evidence or selectively reporting results. Blinding researchers to participant group assignments and using objective measurement criteria help mitigate confirmation bias.

Researchers employ various strategies to assess and enhance validity, reliability, and reduce bias. Pilot testing instruments before full-scale studies, employing statistical techniques such as regression analysis to control for confounding variables, and using mixed-methods approaches to triangulate findings contribute to rigorous research.

The following figure illustrates the relationship between validity, reliability, and bias. Studies with high validity and reliability but minimal bias produce the strongest evidence, whereas research with significant bias or measurement inconsistencies weakens conclusions.

![]() Hot Tip! Always check for funding sources and conflicts of interest in research studies. Industry-sponsored studies may introduce bias, so look for independent replication of findings before accepting conclusions.

Hot Tip! Always check for funding sources and conflicts of interest in research studies. Industry-sponsored studies may introduce bias, so look for independent replication of findings before accepting conclusions.

Exploring Bias Further

Ever ask someone’s opinion about the “best” brand of shoes or “best” local coffee? Their answer is based on their own experience, thus biased to their opinion. Bias is a distortion or an influence that results in an error in inference.

When reading articles, we need to be very aware of the potential for bias. Some examples of factors creating bias include:

- Lack of participants’ candor

- Faulty methods of data collection

- Researcher’s preconceptions

- Participants’ awareness of being in a special study

- Faulty study design

- Survey question design

Survey questions are very commonly biased. With regard to bias in surveys, it is always wise to utilize participant anonymity as this would make it more likely to obtain truthful answers especially when questions are controversially-based.

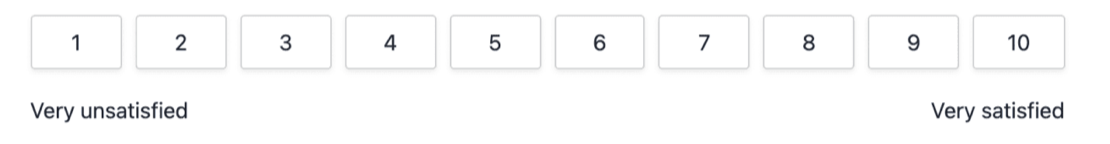

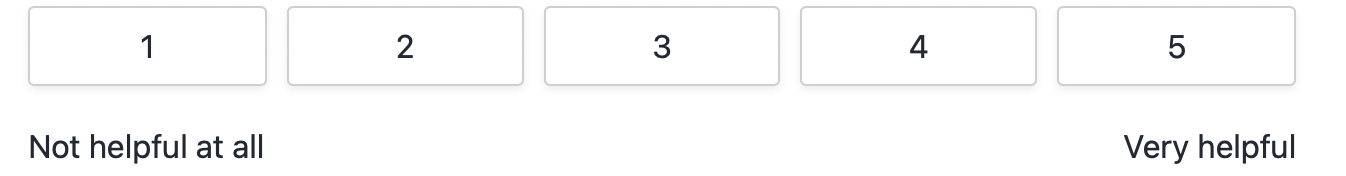

Surveys are used frequently in research, so let’s dive into how surveys can thwart research results. Depending on how they are asked, questions can lead the respondent intentionally down a path to a certain answer or are phrased in a manner that can be confusing to them, leading to unclear responses. The following are some examples:

Leading questions: These are easy to spot, as it is clear there is a “correct” answer that the question is leading you toward. This will always result in false information as there was never an option for an honest response.

Example: “What problems did you have with the product?”

You can see that this question was set up in a way to assume there was something wrong in the first place.

Alternative: “On a scale of 1-10, how satisfied were you with the product?”

Vague or ambiguous questions: On the surface, these can look honest and harmless, but their vague nature can confuse the participant into a poor or inaccurate response.

Example: “How did this hospital experience compare with other hospital experiences?”

Gosh. Have they had other hospital experiences? If not, then what? Is there a benchmark to compare against? What “experience”?… price? Friendly nurses? Good medical care? So much is terrible about this question format.

Alternative: “On a scale of 1-10, with 10 being highly likely, how likely would you be to recommend this hospital to others?”

Double-Barreled Questions: These types of questions ask the participant to provide an opinion on two topics but only provides an opportunity for one response.

Example: “How satisfied are you with your hospital stay and discharge instructions?”

If they are satisfied with the hospital stay but not the discharge instructions, how do they answer this?

Alternative: Split the question into two questions.

Absolute Questions: These questions can bias the participants’ choices by forcing them into an absolutely categorical response when they might not have one. These use words such as “never”, “always”, “will”, etc.

Example: “Do you always have eggs for breakfast?”

The problem with the above example is that the answer will be no. The chances of someone having eggs for breakfast every single day is very slim. Obviously, this skews the data because there are no alterative choices.

Alternative: Give options! “Do you eat of the following for breakfast? Select as many as applicable. Add any foods.”

__ Eggs

__ Bacon

__ Protein Shake

__ Pancakes

__ Fruit

__ Cottage Cheese

__ Other (specify)

__ Other (specify)

Acquiescence Bias Questions: These questions are usually a binary yes/no or agree/disagree choice. Guess what? People are often more likely to respond positively when only two options are presented.

Example: “Is our level of customer service satisfactory?” Yes/No”

We will learn nothing of value form these types of questions.

Alternative: Either offer multiple options or offer an open form text box, such as: “Please describe your experience with customer service.”

Well? Did you find this section on biased survey questions helpful? Just joking.

Lastly, motivated respondent bias occurs when people are highly motivated to complete a survey in hopes of changing public opinion or influencing the outcome of the research. Avoiding acquiescence bias questions absolutely helps to minimize this risk.

Critical Aspects of Appraisal

Critical appraising evidence is an essential step in EBP in response to a clinical question (Polit & Beck, 2021). The process of systematically evaluating research for its reliability, importance, and significance is critical appraisal (Hall & Roussel, 2014). The process is necessary in considering whether the research was conducted appropriately, because not all research is awesome.

Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically assessing the outcome of scientific research (evidence) to judge its trustworthiness, value, and relevance in a particular context. Critical appraisal looks at the way a study is conducted and examines factors such as internal validity, generalizability, and relevance.

Critical appraisal allows us to:

- reduce information overload by eliminating irrelevant or weak studies

- identify the most relevant papers

- distinguish evidence from opinion, assumptions, misreporting, and belief

- assess the validity of the study

- assess the usefulness and clinical applicability of the study

- recognize any potential for bias.

The beginning guidelines for critical appraisal include asking:

- How relevant is the research problem to the actual practice of nursing?

- Was the study quantitative or qualitative? How did you make that determination?

- What was the underlying purpose (or purposes) of the study? (Therapy/Intervention, Diagnosis/Assessment, Prognosis, Etiology/Harm, Description, or Meaning?)

- What might be some clinical implications of this research? To what type of people and settings is the research most relevant? If the things were accurate, how might you use the results of this study?

An inference is a conclusion drawn. It is a challenge to design studies to support inferences that are reliable (accurate and consistent data; concerns the truthfulness in the data obtained and the degree to which any measuring tool controls random error, and if it can be reproduced under the same conditions) and valid (soundness of the evidence; validity is about what an instrument measures and how well it does so, and whether the results really do represent what they were supposed to measure) in quantitative studies, and that are trustworthy in qualitative studies. Thus, every article, even if peer-reviewed, needs to be critically appraised.

Interpreting Statistical Findings in Research Articles

Interpreting statistical findings in research articles is a crucial skill for nurses and healthcare professionals who rely on evidence-based practice. Understanding statistical concepts allows readers to critically evaluate study results, assess their significance, and determine their applicability to clinical practice. Statistical findings provide a framework for interpreting data patterns and making informed healthcare decisions.

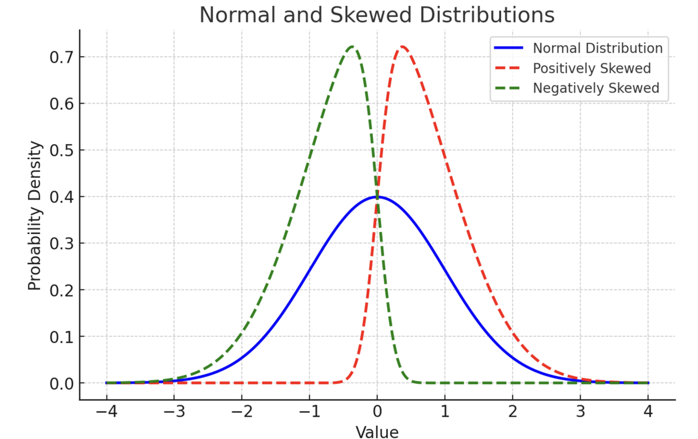

Statistical analysis in research often involves descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics summarize data and provide an overview of the sample characteristics, including measures such as mean, median, mode, standard deviation, and range. Inferential statistics, on the other hand, allow researchers to make conclusions about a population based on a sample by using hypothesis testing, confidence intervals, and regression analysis.

For example, a research article may report that the mean systolic blood pressure of a sample population decreased from 140 mmHg to 125 mmHg after an intervention. While this descriptive statistic provides useful information, inferential statistics, such as a t-test or ANOVA, determine whether this change is statistically significant or could have occurred by chance.

A key concept in statistical analysis is the p-value, which indicates the probability of obtaining the observed results if the null hypothesis were true. A p-value less than 0.05 is commonly considered statistically significant, suggesting that the findings are unlikely due to random chance. However, statistical significance does not always imply clinical significance, emphasizing the importance of interpreting effect sizes and confidence intervals.

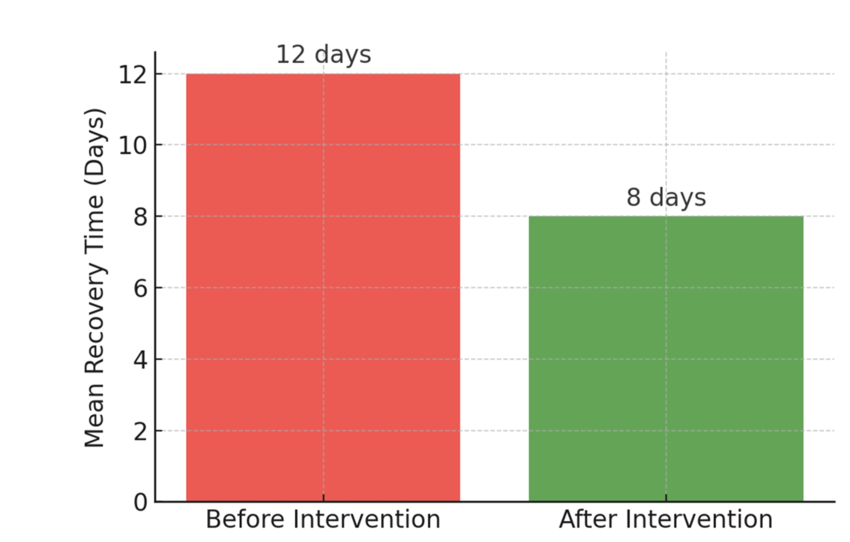

Figures and visual representations, such as bar graphs, scatter plots, and box plots, enhance understanding by displaying data trends. The following figure illustrates the impact of an intervention on patient recovery times, showing how visualizing statistical results facilitates interpretation.

Figure: Impact of an Intervention on Patient Recovery Time

Various Common Statistical Tests

Many research articles include statistical analyses that require interpretation. We will dive into these at a very basic level in an upcoming chapter, but for now be somewhat familiar with these tests. You will likely see these terms in the articles you are reading, so the following list will help you understand what the researchers were measuring:

- Descriptive Statistics – Summarizes data to provide insights into sample characteristics.

- Mean: The average value of a dataset.

- Median: The middle value in a dataset when ordered from lowest to highest.

- Mode: The most frequently occurring value in a dataset.

- Standard Deviation: Measures data dispersion around the mean.

- Range: The difference between the highest and lowest values.

- P-values: Indicate statistical significance, with p < 0.05 typically considered significant.

- Confidence Intervals (CIs): Show the range in which the true effect likely falls.

- T-Test – Compares the means of two groups to determine if they are statistically different.

- Independent t-test: Compares means between two unrelated groups (e.g., control vs. treatment).

- Paired t-test: Compares means from the same group at different time points (e.g., before and after an intervention).

- Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) – Compares means among three or more independent groups.

- One-way ANOVA: Tests for differences between multiple groups based on one independent variable.

- Two-way ANOVA: Examines the effect of two independent variables on a dependent variable.

- Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) – Extends ANOVA by evaluating multiple dependent variables simultaneously.

- Chi-Square Test – Assesses whether categorical variables are related (e.g., comparing proportions of patients who recover based on different treatments).

- Correlation Analysis – Determines the strength and direction of a relationship between two continuous variables.

- Pearson’s correlation (r): Measures linear correlation between two continuous variables.

- Spearman’s correlation: Evaluates monotonic relationships between two ranked variables.

- Regression Analysis – Predicts outcomes based on relationships between variables.

- Linear Regression: Models the relationship between one independent variable and a dependent variable.

- Multiple Regression: Includes two or more independent variables to predict an outcome.

- Logistic Regression: Predicts a binary outcome (e.g., success/failure).

- Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test – A non-parametric test used for comparing paired data when the normality assumption is not met.

- Mann-Whitney U Test – A non-parametric alternative to the independent t-test for comparing two independent groups when normality is not assumed.

- Kruskal-Wallis Test – A non-parametric alternative to ANOVA for comparing three or more independent groups.

- Fisher’s Exact Test – Used for small sample sizes to test relationships between categorical variables.

- Cohen’s d – Measures effect size, which indicates the magnitude of the difference between two groups.

- Confidence Intervals – Provide a range of values within which the true population parameter is expected to fall with a specified level of confidence (e.g., 95% CI).

- Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis – Estimates the time until an event occurs, such as disease progression or patient recovery.

- Cox Proportional Hazards Model – Evaluates the effect of multiple variables on survival times.

- Factor Analysis – Identifies underlying factors within a set of observed variables, commonly used in psychometric research.

- Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) – Tests complex relationships among multiple variables, often used in social sciences.

You might see figures like the following, which are created to gather some sense of organization to data. We will explore this further when we dive into statistics in an upcoming module.

![]() Hot Tip! A p-value below 0.05 might indicate statistical significance, but that doesn’t mean the results are clinically meaningful. Always consider effect size, confidence intervals, and real-world applicability when appraising evidence. We will come back to this in the Data Analysis chapter.

Hot Tip! A p-value below 0.05 might indicate statistical significance, but that doesn’t mean the results are clinically meaningful. Always consider effect size, confidence intervals, and real-world applicability when appraising evidence. We will come back to this in the Data Analysis chapter.

Practical Application

Nurses and healthcare providers frequently rely on research to guide clinical practice, but not all studies are created equal. Understanding how to critically appraise evidence is crucial for ensuring patient safety, ethical care, and the effective implementation of new interventions. This practice application will guide learners through an appraisal exercise, focusing on identifying potential biases, ethical concerns, and clinical applicability of research findings.

Activity: You are a nurse serving on the hospital’s Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) Committee, tasked with evaluating a recent study on a new hydration protocol for elderly patients in long-term care facilities. The study claims that increasing fluid intake by 25% reduces hospital admissions due to dehydration-related complications. The research, however, was funded by a company that manufactures electrolyte-enriched hydration products, and all participants received the company’s product rather than standard fluids like water or juice.

As a committee member, your role is to:

- Assess the study design – Was the research randomized, controlled, and blinded?

- Evaluate the funding and conflicts of interest – Does industry sponsorship affect credibility?

- Consider generalizability – Can the findings be applied to your patient population?

- Weigh ethical considerations – Is promoting this protocol justified given the potential bias?

Ethical Dilemma Example: A heated discussion arises within the committee. The hospital administration is eager to adopt the hydration protocol because the company has offered discounted product pricing and marketing support if the hospital implements the intervention. However, some committee members question the reliability of the research, noting the lack of independent studies and the potential conflict of interest in the study’s funding.

A nurse researcher on the committee advocates for caution, arguing that using only electrolyte-enriched beverages could unintentionally increase costs for patients and caregivers, while standard water intake might provide similar benefits at a lower cost. Others argue that delaying implementation might prevent potential patient benefits, even if the study has some limitations.

Conclusion: After rigorous discussion, the committee decides to conduct a small internal trial comparing standard hydration protocols to the company’s product before making a hospital-wide decision. They also request further independent research before recommending full adoption.

Research Control

Research control is one way that researchers can address bias. In quantitative studies, randomness is often utilized. This allows certain aspects of the study to be left to chance rather than to researcher or participant choice. Randomization is the process of assigning participants to treatment and control groups, assuming that each participant has an equal change of being assigned to any group. The most common and basic method of simple randomization is flipping a coin. For example, with two treatment groups (control versus treatment), the side of the coin (i.e., heads – control, tails – treatment) determines the assignment of each subject.

However, subjects in various groups should not differ in any systematic way. If treatment groups are systematically different, research results will be biased. Suppose that subjects are assigned to control and treatment groups in a study examining the efficacy of a surgical intervention. If a greater proportion of older subjects are assigned to the treatment group, then the outcome of the surgical intervention may be influenced by this imbalance. The effects of the treatment would be indistinguishable from the influence of the imbalance of variables, thereby requiring the researcher to control for the variables in the analysis to obtain an unbiased result.

Sometimes, for example collecting a large aggregate dataset, the researcher will choose to randomly select a particular number of data to utilize such as every third data point. Remember our Level of Evidence Hierarchy? The levels are ranked according to study types that tend to feature more control over bias.

Blinding is used in some studies to prevent biases stemming from people’s awareness. This involves concealing information from participants, data collectors, or care providers to enhance the objectivity.

Critiquing Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research

Research in nursing and healthcare is broadly categorized into quantitative and qualitative approaches. Both methodologies provide valuable insights, but they require distinct appraisal techniques due to their differences in data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

Quantitative research is characterized by numerical data, structured methodologies, and statistical analyses. Studies often employ experimental, quasi-experimental, or observational designs to examine relationships between variables. When critiquing quantitative research, focus is placed on study design, sample size, measurement validity, and statistical analyses. Ensuring that the study adheres to rigorous sampling techniques, appropriate statistical tests, and controls for bias is essential.

In contrast, qualitative research explores experiences, perceptions, and meanings through interviews, focus groups, or observations. It seeks to understand human behaviors in their natural settings, often utilizing methods such as thematic analysis or grounded theory. Critiquing qualitative research requires assessing the trustworthiness, credibility, dependability, and confirmability of findings. Researchers enhance rigor through prolonged engagement, member checking, and triangulation, ensuring that interpretations are reflective of participants’ experiences.

A key difference between these approaches is the nature of the research questions they address. Quantitative research typically asks “how much” or “what is the relationship between variables,” while qualitative research explores “why” or “how” phenomena occur. A comprehensive critique must consider whether the chosen methodology aligns with the research question and the study’s broader objectives.

- Quantitative Research: Involves numerical data, structured methodologies, and statistical analyses. Appraisal focuses on study design, sampling, and statistical validity.

- Qualitative Research: Explores experiences, perceptions, and meanings. Appraisal emphasizes rigor, trustworthiness, and credibility.

Table: Distinctions between Quantitative and Qualitative Research

| Aspect | Quantitative Research | Qualitative Research |

| Data Type | Numerical | Descriptive |

| Research Focus | Cause & Effect | Understanding Experiences |

| Analysis | Statistical | Thematic |

| Results | Generalizable | Context-Specific |

| Example Methods | Surveys, Experiments | Interviews, Observations |

Ponder This

Consider the potential risks of assuming benefit without clear evidence versus the ethical implications of withholding potentially beneficial therapies due to uncertainty. How can research and clinical practice evolve to ensure both patient safety and progress in care?

Common Errors and Red Flags in Research Studies

Recognizing common errors and red flags in research studies is essential for ensuring that evidence used in clinical decision-making is reliable and valid, and can prevent reliance on flawed research. Errors in research design, analysis, and reporting can significantly compromise findings, leading to misguided conclusions and potential harm in healthcare applications.

Sample Sizes

One of the most critical red flags is small sample sizes that are used to make broad generalizations. A study with only a handful of participants lacks statistical power and may not adequately represent the larger population. Without sufficient sample size, findings may be due to chance rather than actual relationships, reducing the credibility of the study.

Control Groups

Another key issue is inadequate control groups in experimental studies. Without a properly matched control group, it is difficult to determine whether an intervention truly caused the observed effect. Studies that fail to account for confounding variables, such as patient demographics or external influences, risk producing biased results.

Publication Bias

Selective reporting of positive results, also known as publication bias, is another common issue. Researchers or journals may only publish studies with statistically significant findings while disregarding studies with null or negative results. This creates a skewed perspective on a topic, making interventions appear more effective than they actually are. Transparency in reporting all study results, including those that do not support hypotheses, is crucial for maintaining integrity in research.

Conflict of Interest

Conflicts of interest or industry funding without disclosure can also undermine the credibility of a study. If researchers have financial ties to pharmaceutical companies or medical device manufacturers, their findings may be influenced by vested interests rather than objective scientific inquiry. Full disclosure of funding sources and potential conflicts of interest allows readers to assess the potential for bias.

Other Errors

Other errors include inappropriate statistical analyses, lack of reproducibility, and failure to consider ethical implications. Researchers should use appropriate statistical tests to analyze data and ensure that their methodology can be replicated in future studies. Ethical considerations, including informed consent and participant safety, must also be thoroughly evaluated in all research studies.

![]() Hot Tip! Abstracts often highlight only positive findings. To fully assess the study, examine the methods, sample size, limitations, and discussion to uncover potential weaknesses or biases that may not be immediately apparent.

Hot Tip! Abstracts often highlight only positive findings. To fully assess the study, examine the methods, sample size, limitations, and discussion to uncover potential weaknesses or biases that may not be immediately apparent.

Ponder This

Consider a scenario where a research study on infection control suggests that a specific hand hygiene protocol reduces hospital-acquired infections by 50%. How would you critically appraise this study before integrating it into your practice? What factors would you examine, and how would you determine if the findings are applicable to your healthcare setting?

Critiquing Secondary Research

Secondary research, including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and integrative reviews, plays a critical role in evidence-based practice by synthesizing findings from multiple primary studies. While these reviews offer a broad perspective on a given topic, their validity and reliability depend on several key factors, including methodological rigor, the quality of the included studies, and the approach used to analyze and synthesize data. Critically appraising secondary research requires careful consideration of how the study was conducted, the potential for bias, and the applicability of the findings to clinical practice.

A fundamental aspect of critiquing secondary research is evaluating the clarity and relevance of its research question. A well-conducted systematic review or meta-analysis should be grounded in a well-defined question that guides the selection of studies and the synthesis of findings. Often, frameworks such as PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) help structure the research focus, ensuring that the review remains relevant to clinical decision-making. If the research question is vague or lacks a clear focus, the resulting analysis may lack direction, reducing its usefulness in guiding practice.

The methodology used to identify and select studies is another essential area for critique. A high-quality systematic review should employ a comprehensive and transparent search strategy that minimizes selection and confirmation bias. This includes searching multiple reputable databases, using well-constructed search terms, and applying predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Without a thorough search strategy, there is a risk that relevant studies may be omitted, leading to an incomplete or skewed representation of the available evidence. The inclusion and exclusion criteria should also be explicitly stated and justified, ensuring that the selection process is objective and systematic rather than arbitrary.

Beyond the selection of studies, the quality of the included research significantly impacts the validity of a secondary analysis. Strong systematic reviews and meta-analyses use standardized tools to assess study quality, such as the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomized controlled trials or the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies. Without a rigorous quality assessment, the inclusion of poorly designed or biased studies may weaken the overall conclusions of the review. A critical reader should examine whether the authors transparently report their assessment process and whether they account for variations in study quality when interpreting their results.

The way data is synthesized in secondary research also requires careful evaluation. Some reviews use a narrative synthesis, summarizing and comparing findings across studies, while meta-analyses employ statistical techniques to pool data and calculate overall effect sizes. When critiquing a meta-analysis, it is important to assess whether appropriate statistical methods were used to calculate effect sizes and whether heterogeneity among studies was considered. High heterogeneity, which reflects significant variation in study findings, can challenge the validity of pooled results. Strategies such as subgroup analyses or random-effects models may help account for these differences, and their use should be justified within the review.

Bias is an ever-present concern in secondary research, influencing both the selection of studies and the interpretation of findings. Publication bias, where studies with positive or significant results are more likely to be published, can distort a review’s conclusions if not properly addressed. Researchers often assess publication bias using tools such as funnel plots or statistical tests like Egger’s test. Additionally, reviewer bias may arise if study selection, data extraction, and synthesis are not conducted independently by multiple researchers. A well-conducted review should clearly describe how disagreements between reviewers were resolved, ensuring that findings are not unduly influenced by individual perspectives.

Finally, it is essential to consider the applicability of secondary research findings to clinical practice. Even a well-conducted review may have limited generalizability if the included studies focus on a narrow population or setting. Clinicians and researchers must assess whether the interventions and outcomes examined in the review are relevant to their specific patient populations and healthcare contexts. Additionally, a strong secondary study should acknowledge its limitations, discussing potential gaps in the evidence and providing recommendations for future research.

Ethical Considerations in Research Appraisal

Ethical issues in research appraisal include:

- Ensuring the study adheres to ethical guidelines (e.g., informed consent, IRB approval).

- Avoiding misinterpretation or misuse of research findings.

- Maintaining professional integrity when incorporating evidence into practice.

Ethical Dilemma Example

A long-term care facility is considering the implementation of an experimental sensory stimulation therapy (SST) aimed at improving cognitive function and emotional well-being in non-verbal patients with advanced neurological conditions (e.g., late-stage ALS, advanced dementia, locked-in syndrome). The therapy involves immersive experiences using light, sound, and tactile stimulation, with proponents arguing that it enhances brain activity and emotional response.

The facility director is eager to introduce SST, citing early promising studies and potential benefits for patients with severe communication barriers. However, a speech-language pathologist (SLP) and an occupational therapist (OT) express ethical concerns. The therapy has not undergone rigorous large-scale clinical trials, and while anecdotal reports suggest improvements in patient responsiveness, there is no clear way to obtain direct patient consent or assess distress in non-verbal individuals. Some family members are enthusiastic, but others are skeptical, fearing it may cause sensory overload or discomfort that the patient cannot express.

Actions:

- Evaluate the Evidence Base: The SLP and OT review published research and find that SST has been tested mostly in pediatric and mild cognitive impairment populations, but limited studies exist in patients with profound communication barriers.

- Assess Ethical Implications of Informed Consent: Many patients in the facility are non-verbal due to neurological conditions. Some have clear advance directives, but others do not. The team debates whether proxy consent from families is sufficient, particularly if the patient’s response cannot be measured in real time.

- Consider Risks of Sensory Overload: While proponents highlight benefits, opponents worry about distress. The team consults with neurologists and behavioral specialists on how to monitor non-verbal signs of discomfort (e.g., facial expressions, heart rate variability, agitation).

- Pilot the Therapy with Safeguards: The facility agrees to conduct a small pilot study with continuous patient monitoring, pre-defined withdrawal criteria (e.g., if distress is suspected), and a diverse sample that includes different neurological conditions.

- Obtain Ethics Committee Review: The ethics board is consulted, emphasizing the balance between potential benefit and unknown harm in a vulnerable population. They recommend enhanced family education on risks, benefits, and limitations before consent is granted.

Conclusion:

The facility ultimately proceeds with a limited pilot, ensuring that patients are monitored closely for distress, and families are fully informed of the uncertainties. After six months, the study finds mixed results—some patients show increased engagement (eye tracking, micro-expressions), while others appear overstimulated. Based on these findings, the facility decides not to implement SST as a standard practice but instead offers it selectively, only for patients with strong family advocacy and documented signs of enjoyment.

In summary, appraising research is a critical skill in evidence-based practice, ensuring that healthcare decisions are grounded in credible, reliable, and ethically sound evidence. By understanding the principles of validity, reliability, and bias, professionals can critically evaluate research findings and distinguish between statistically significant results and clinically meaningful applications. Recognizing common errors and red flags prevents reliance on flawed studies, while ethical considerations help safeguard patient welfare and scientific integrity. Whether interpreting statistical findings, critiquing research methodologies, or addressing ethical dilemmas, nurses and healthcare providers must approach research with a discerning eye and a commitment to best practices. Strengthening these appraisal skills enables the integration of high-quality evidence into patient care, ultimately improving outcomes and advancing the profession.

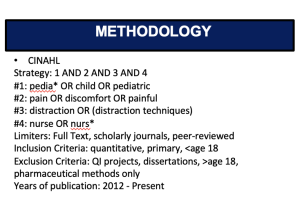

EBP Poster Application! At this point, you should have the following completed for your EBP Poster Draft:

- Title

- Introduction

- Clinical Question

- Methodology (at least, the start of it)

- Minimum of 8 articles on your Synthesis of Literature Table (get them listed! You can always change them later.)

- Very rough notes under the Results Section. Just jot stuff down. Edit later. Don’t worry about this.

Here is an example of a poster’s Methodology section:

Summary Points

Appraisal in EBP ensures that clinical decisions are based on credible, relevant, and high-quality research.

Peer review filters out poor-quality work but is not a guarantee of rigor—critical appraisal is still necessary.

Purpose of appraisal is to judge study trustworthiness, identify bias, and evaluate applicability to nursing practice.

Key elements of a critique include: study purpose, design, literature review, hypothesis/question, sample, data collection, results, and recommendations.

IMRAD structure (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) is the standard format for research articles, guiding systematic reading.

Introduction section explains background, problem statement, literature review, knowledge gaps, and rationale for the study.

Methods section describes research design, sampling, measurement tools, procedures, ethics, and analysis—critical for evaluating validity and bias control.

Results section presents findings objectively, often with statistics (quantitative) or themes/quotes (qualitative); interpretation is reserved for the discussion section.

Discussion section links results back to literature, acknowledges limitations, addresses bias, and considers clinical implications.

Critical appraisal tools (CASP, JBI, GRADE, PRISMA) provide structured checklists for evaluating different study types.

Validity (internal, external, construct, criterion) assesses accuracy of study findings and their applicability.

Reliability (test-retest, inter-rater, internal consistency) measures the consistency and stability of results over time.

Bias can arise from selection, measurement, confirmation, funding sources, or poor study design—identifying and controlling bias is crucial.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative critique: quantitative emphasizes sample size, statistical rigor, and control; qualitative emphasizes trustworthiness, credibility, and depth of interpretation.

Red flags in quantitative research include small sample sizes, inadequate controls, lack of reproducibility, selective reporting, and conflicts of interest.

Secondary research appraisal (systematic reviews, meta-analyses) focuses on search rigor, study inclusion quality, bias control, and synthesis method.

Statistics in appraisal require interpreting descriptive measures (mean, median, SD), inferential tests (t-tests, ANOVA, regression), p-values, effect sizes, and confidence intervals.

Ethical appraisal includes checks for IRB approval, informed consent, conflict of interest, and responsible interpretation of findings.

Application to practice requires weighing statistical and clinical significance, population relevance, and feasibility before integrating evidence into care.

Case Study: Evaluating a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program for Night-Shift Nurses

Nurses working night shifts often experience high levels of stress, sleep disturbances, and burnout, which can negatively impact patient care and personal well-being. Traditional stress management interventions, such as counseling or wellness programs, have shown limited engagement and effectiveness among night-shift workers. Emerging research suggests that Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) may improve resilience, sleep quality, and overall well-being in high-stress professions. However, its effectiveness for night-shift nurses in acute care settings remains largely unexamined.

The Problem:

A hospital’s Nursing Wellness Committee is exploring strategies to reduce stress and improve well-being for night-shift nurses. Administrators are skeptical about dedicating resources to a mindfulness program without clear evidence of its benefits. The committee needs strong, research-based evidence to determine whether an MBSR program is a viable intervention.

Research Question:

Does participation in a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program improve stress levels, sleep quality, and job satisfaction among night-shift nurses in an acute care hospital setting?

Hypothesis:

Night-shift nurses who participate in an 8-week MBSR program will experience significantly lower stress levels, improved sleep quality, and higher job satisfaction compared to nurses who do not participate in the program.

Study Design:

- Type: Quasi-experimental, two-group pre-test/post-test design

- Participants: 80 night-shift nurses working in an acute care hospital

- Sampling Method: Convenience sampling with voluntary participation

- Groups:

- Intervention Group: 40 nurses enrolled in the 8-week MBSR program

- Control Group: 40 nurses following usual stress management practices

- Data Collection Tools:

- Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

- Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

- Nursing Job Satisfaction Survey (NJSS)

- Timeline:

- Baseline assessments before intervention

- Midpoint assessment at 4 weeks

- Final assessment at 8 weeks

- Follow-up at 12 weeks to evaluate sustained effects

Implementation:

- Recruitment & Consent: Night-shift nurses were invited to participate, with informed consent obtained before enrollment.

- MBSR Program:

- o Weekly 60-minute guided mindfulness sessions (breathing techniques, body scans, meditation).

- o Daily self-guided mindfulness exercises via a mobile app.

- o Reflection journals to track mindfulness practice and perceived stress levels.

- Control Group: Continued routine hospital stress management resources but did not receive mindfulness training.

- Assessment: Data collected at baseline, 4 weeks, 8 weeks, and a 12-week follow-up.

Outcomes:

- Stress Reduction: Nurses in the MBSR group reported a 30% reduction in stress scores compared to only a 10% reduction in the control group.

- Sleep Quality Improvement: The intervention group showed significant improvements in sleep duration and quality, while control group participants reported no meaningful changes.

- Job Satisfaction: Nurses in the MBSR group reported higher job satisfaction (average increase of 15%), while the control group showed no significant improvement.

Conclusion:

The findings suggest that MBSR is an effective intervention for reducing stress, improving sleep quality, and enhancing job satisfaction among night-shift nurses. Given these results, the hospital’s Nursing Wellness Committee recommends integrating MBSR into ongoing staff wellness initiatives. However, further research with randomized controlled trials and long-term follow-up is needed to assess the sustainability of these benefits over time.

References & Attribution

“Green check mark” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

“Light bulb doodle” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

“Magnifying glass” by rawpixel licensed CC0

“Orange flame” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

Gray, J. R., Grove, K. S., & Sutherland, S. (2021). Burns & Grove’s The practice of nursing research: Appraisal, synthesis, and generation of evidence (9th ed.). Saunders Elsevier.

Haedtke, C., Smith, M., VanBuren, J., Kein, D., Turvey, C. (2017). The relationships among pain, depression, and physical activity in patients with heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 32(5), E21-E25.

Hall, H. & Roussel, L. (2014). Evidence-based practice: An integrative approach to research, administration, and practice. Jones & Bartlett.

Polit, D. & Beck, C. (2021). Lippincott CoursePoint Enhanced for Polit’s Essentials of Nursing Research (10th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health.

Shannonhouse, L., Barden, S., & Jones, E. (2016). Secondary traumatic stress for trauma researchers: A mixed methods research design. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 38(3), 201-216.

Walker, C., Kappus, K., & Hall, N. (2016). Strategies for improving patient throughput in an acute care setting resulting in improved outcomes: A systematic review. Nursing Economics, 34(6), 277-288.