Research Ethics

In this chapter, we will be exploring some historical factors regarding human subject ethics in order to understand the ethical practices we have in place today. We will also explore how we go about ensuring human subject protection during research projects.

Content:

- Morals, Ethics, and Values

- Ethical Principles

- Historical Aspects of Research Ethics

- Key Ethical Principles in Research

- Institutional Review Board

- Ethical Principles and Protecting Study Participants

Objectives:

- Describe historical aspects that led to the creation of various codes of ethics.

- Define key ethical principles in research.

- Describe an Institutional Review Board’s key goals.

- Identify procedures to adhere to ethical principles and protect study participants.

Key Terms:

Autonomy: The ability to make your own decisions and have control over your actions without external pressure or influence.

Beneficence: A fundamental ethical principle in healthcare that means actively doing good, above all else doing no harm, and promoting the well-being of others.

Ethical dilemma: A ethical dilemma is a situation in which the rights of study participants are in direct conflict with the requirements of a study.

Ethics: Systematic rules or guidelines that govern behavior in a particular context, often established by an external body or profession.

Fidelity: Refers to the ethical principle of being faithful, loyal, and keeping promises to patients and colleagues.

Justice: The ethical principle that emphasizes fairness, equality, and impartiality in the distribution of care and resources.

Nonmaleficence: An ethical principle in healthcare that means “do no harm.” It’s the commitment to avoid causing injury or suffering to patients.

Morals: Traditions or beliefs about right and wrong conduct.

Values: Personal beliefs or standards that an individual holds important.

Veracity: The ethical principle of being honest and truthful in all interactions.

Introduction

In the rapidly evolving healthcare field, evidence-based practice and research form the backbone of clinical decision-making and patient care. For entry-level nursing students, understanding the ethical principles that guide research is not only fundamental to their education but also to their future roles as healthcare professionals. Ethical considerations in research are crucial to ensure that studies are conducted with integrity, respect, and responsibility, safeguarding the rights and well-being of all participants involved. Important to note, is that an ethical dilemma, which is often faced in research, is a situation in which the rights of study participants are in direct conflict with the requirements of a study.

This chapter will introduce you to the core ethical principles that underpin research in nursing and healthcare. As you embark on your journey into evidence-based practice, it is essential to grasp the importance of ethics in research to protect participants, maintain the credibility of the nursing profession, and contribute to the advancement of knowledge. We will explore key concepts such as informed consent, confidentiality, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice, which are the cornerstones of ethical research.

By the end of this chapter, you will have a solid understanding of how ethical principles are applied in research, the importance of ethical oversight, and your responsibilities as a nursing student and future researcher. This knowledge will empower you to critically evaluate research studies and ensure that your own practice aligns with the highest ethical standards, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes and a stronger, more ethical healthcare environment.

Morals, Ethics, and Values

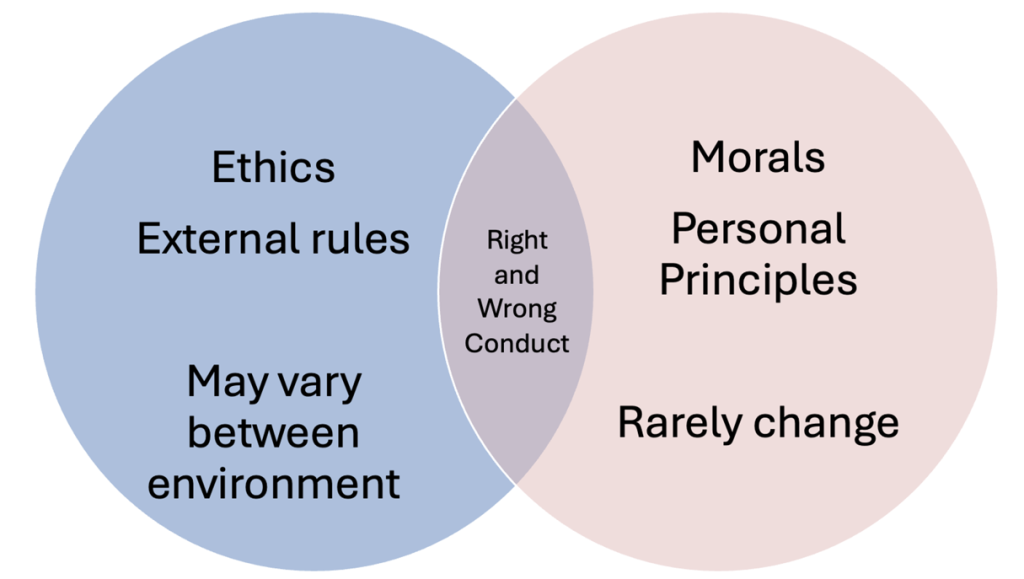

Morals, values, and ethics are often used interchangeably, but they represent distinct concepts that guide human behavior and decision-making, particularly in the context of nursing and healthcare.

Morality refers to “traditions or beliefs about right and wrong conduct” and is influenced by social and cultural practices, whereas ethics is “the study of social morality” (Burkhardt & Nathaniel, 2014, p. 35). Morals are to the principles or rules that an individual or group considers to be right or wrong. These are often deeply rooted in cultural, religious, or societal norms and can vary significantly from one person or community to another. Morals guide personal behavior and are typically associated with a sense of duty or obligation to do what is perceived as “right” or to avoid what is perceived as “wrong.”

Values are the personal beliefs or standards that an individual holds important. They are shaped by experiences, culture, education, and family influences. Values guide an individual’s choices and actions in a broader sense, not necessarily tied to a sense of right or wrong but rather to what is important and meaningful to them. For example, a nurse may value compassion, integrity, or excellence in patient care, which influences their approach to their work.

Resnick (2020) defines ethics as “norms for conduct that distinguishes between acceptable and unacceptable behavior” (p. 1 of 12). Ethics are the systematic rules or guidelines that govern behavior in a particular context, often established by an external body or profession. Ethics are more formalized than morals and values, providing a framework for decision-making in professional practice. In nursing, ethical guidelines are developed by professional organizations and serve to protect the rights of patients, ensure fair treatment, and promote trust in the healthcare system. Ethical principles such as autonomy, justice, beneficence, and non-maleficence are applied to ensure that nurses act in the best interests of their patients and the public.

Figure Above: Venn Diagram of Ethics vs. Morals

Ethical Principles

In health care, professional codes of ethics incorporate several basic principles to help guide healthcare professionals in determining right from wrong and in making ethical decisions. These basic principles include autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, veracity, justice, and fidelity.

Autonomy: Autonomy refers to the principle that individuals have the right to make their own decisions and choices, free from coercion or interference. In the research context, autonomy is respected through informed consent, where participants are fully informed about the study and voluntarily choose to participate. It’s like having the steering wheel in your hands and overseeing your own direction, whether it’s in life, work, or healthcare.

Beneficence: Beneficence is the ethical principle that emphasizes the obligation to act in the best interests of others, promoting good and preventing harm. In research, beneficence involves designing studies that maximize potential benefits to participants and society while minimizing potential risks. It’s all about taking actions that help, protect, and benefit patients, aiming to improve their health and overall quality of life. Think of it as the “do good” rule—nurses and healthcare providers strive to provide care that has the patient’s best interests at heart, whether it’s through providing treatments, offering comfort, or simply being a supportive presence all while, above all else, doing no harm.

Nonmaleficence: Nonmaleficence is the principle of “do no harm.” It requires that researchers avoid causing harm to participants, whether physical, psychological, social, or legal. This principle is closely related to beneficence, as it emphasizes the importance of minimizing risks and ensuring that the benefits of the research outweigh any potential harm.

Veracity: Veracity is the commitment to truthfulness and honesty. In research, veracity involves providing accurate and complete information to participants, ensuring that they are fully informed about the nature of the study, its risks, benefits, and any potential conflicts of interest. Veracity is essential for maintaining trust between researchers and participants.

Justice: Justice in research refers to the ethical obligation to ensure fairness in distributing the benefits and burdens of research. This principle requires that all participants are treated equitably and that no group is unfairly burdened or excluded from the potential benefits of the research. It also involves carefully considering the selection of research participants to avoid exploitation or discrimination. In nursing, justice means treating all patients with respect and without discrimination, advocating for equitable access to healthcare services, and making decisions that are fair and unbiased. It involves balancing resources, prioritizing care based on needs, and working towards reducing health disparities. Essentially, justice is about doing what’s fair and just, ensuring that every patient is treated with the dignity and fairness they deserve.

Fidelity: Fidelity is the principle of faithfulness and loyalty. In the context of research, fidelity involves maintaining trust with participants by honoring commitments, upholding ethical standards, and ensuring that the research is conducted with integrity. It also includes the responsibility to keep promises made to participants, such as maintaining confidentiality and adhering to the study’s protocol. It’s all about maintaining trust and integrity in the nurse-patient relationship by being honest, dependable, and following through on your commitments. Imagine it as the glue that holds the professional relationship together—being true to your word and consistently delivering care that aligns with the values and needs of your patients.

Many occupations have a professional code of ethics to provide a more formal process for applying moral philosophy and to “govern professional behavior” (Burkhardt & Nathaniel, 2014, p. 35). In nursing, the American Nurses Association (ANA) has a “Code of Ethics for Nurses”. This code of ethics guides the practice of nursing and is “the promise that nurses are doing their best to provide care for their patients and their communities and are supporting each other in the process so that all nurses can fulfill their ethical and professional obligations” (ANA, 2015).

Historical Aspects of Research Ethics and Key Ethical Principles in Research

We learn from history. Hopefully, atrocities in history teach us to do better and not make the same mistakes. However, we must not forget history and this is especially true in research. Unfortunately, violations of ethical principles and the moral code have occurred as recent as the last few centuries.

Let’s learn about some key history events that have resulted in harm to humans and some ethical codes that have resulted from these events.

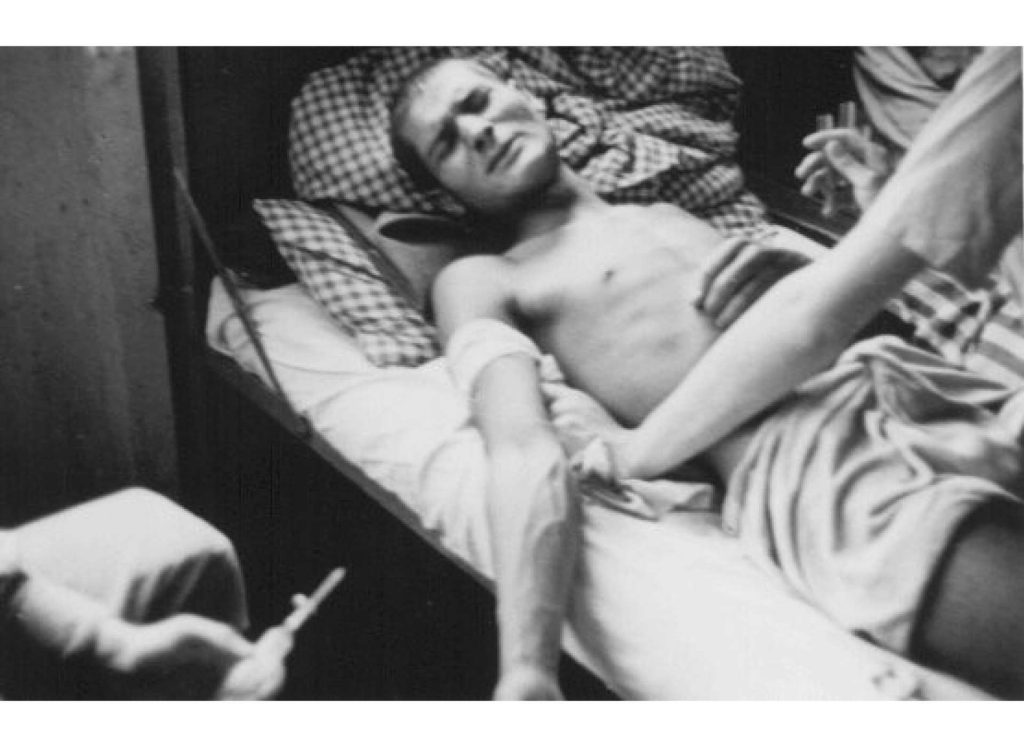

World War II/Nazi Experiments

Between 1939 and 1945, at least seventy medical research projects involving cruel and often lethal experimentation on human subjects were conducted in Nazi concentration camps. More than seven thousand victims of such medical experiments have been documented. Victims include Jews, Poles, Roma (Gypsies), political prisoners, Soviet prisoners of war, homosexuals, and Catholic priests.

Nazi physicians organized trials of antibiotic and homoeopathic treatments in the concentration camps at Dachau and Ravensbrück. Healthy prisoners were given injections from the festering tissues of other inmates who had wound infections. In some people, small pieces of wood and glass were placed in open wounds, in order to mimic war injuries more realistically. The victims were then treated with homoeopathic preparations or various applications of sulfonamides; some received no therapy at all. About a third of the victims died. All these experiments followed a scientific logic that was outdated at the time, and which took no account whatever of the wellbeing of those involved in research. The surviving victims had irreversible physical damage and severe psychological trauma (Roelcke, 2004).

Experiments in the context of aviation medicine were aimed at finding methods to help pilots survive after their planes had been hit at very high altitudes, or after an emergency landing at sea. The experiments, carried out in the Dachau concentration camp, focused on physiological questions, such as the effects on the human body of low pressure at high altitude, or of drinking salt water. For the high-altitude experiments, about 200 people were chosen from the camp prisoners, at least 70 of whom died during the experiments in a specially designed low-pressure cabin, or were killed afterwards to study the pathological changes in their brains. Judged strictly on scientific terms, the methods and results of some of these experiments were apparently innovative and useful. The US Air Force continued some of this research after the war and published the results in cooperation with a number of German physicians involved in the original experiments.

The existing evidence illustrates an inherent logic of these research endeavors: the urge to establish new knowledge superseded any respect for the people who suffered in these experiments. Faced with the challenge of a given medical question, researchers sought opportunities to carry out the experiments required to solve it. It was in concentration camps, asylums, and hospitals in the occupied territories that they found these opportunities because existing legal regulations and sanctions did not apply there (Roelcke, 2004).

The list goes on… freezing/hypothermia experiments, twin children experiments, radiation exposure experiments… all with a common theme: The victims had no choice whether or not to participate. Even after the Nuremberg Code resulted from these experiments, with the first principle of “Informed Consent”, the next atrocity happened years later: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Had we not learned?

Image Above: A Romani (Gypsy) victim of Nazi medical experiments to make seawater safe to drink. Dachau concentration camp, Germany, 1944. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/gallery/nazi-medical-experiments-photographs

Tuskegee Syphilis Study

The U.S Public Health Service (USPHS) Syphilis Study at Tuskegee was a clinical study conducted between 1932 and 1972. The study was intended to observe the natural history of untreated syphilis. As part of the study, researchers did not collect informed consent from participants and they did not offer treatment, even after it was widely available. The study ended in 1972 on the recommendation of an Ad Hoc Advisory Panel, convened by the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs, following publication of news articles about the study. In 1997, President Clinton issued a formal Presidential Apology, in which he announced an investment to establish what would become The National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care at Tuskegee University. Many records can be found in the National Archives.

After the study, sweeping changes to standard research practices were made. Efforts to promote the highest ethical standards in research are ongoing today (CDC, 2022).

Image Above: Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Men who participated in the experiment, part of a collection photos in the National Archives labeled “Tuskegee Syphilis Study. 4/11/1953-1972.” https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/05/16/youve-got-bad-blood-the-horror-of-the-tuskegee-syphilis-experiment/

Key Ethical Principles in Research

Nuremberg Code

In response to the Nazi experiments, a trial of war criminals resulted which resulted in the Nuremberg Code. The main trial at Nuremberg after World War II was conducted by the International Military Tribunal. The tribunal was made up of judges from the four allied powers (the United States, Britain, France, and the former Soviet Union) and was charged with trying Germany’s major war criminals. After this first-of-its-kind international trial, the United States conducted 12 additional trials of representative Nazis from various sectors of the Third Reich, including law, finance, ministry, and manufacturing, before American Military Tribunals, also at Nuremberg. The first of these trials, the Doctors’ Trial, involved 23 defendants, all but 3 of whom were physicians accused of murder and torture in the conduct of medical experiments on concentration-camp inmates.

The resulting Nuremberg Code has the following principles:

- The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.

- The experiment should be such as to yield fruitful results for the good of society, unprocurable by other methods or means of study, and not random and unnecessary in nature.

- The experiment should be so designed and based on the results of animal experimentation and a knowledge of the natural history of the disease or other problem under study that the anticipated results will justify the performance of the experiment.

- The experiment should be so conducted as to avoid all unnecessary physical and mental suffering and injury.

- No experiment should be conducted where there is an a priori reason to believe that death or disabling injury will occur; except, perhaps, in those experiments where the experimental physicians also serve as subjects.

- The degree of risk to be taken should never exceed that determined by the humanitarian importance of the problem to be solved by the experiment.

- Proper preparations should be made and adequate facilities provided to protect the experimental subject against even remote possibilities of injury, disability, or death.

- The experiment should be conducted only by scientifically qualified persons. The highest degree of skill and care should be required through all stages of the experiment of those who conduct or engage in the experiment.

- During the course of the experiment the human subject should be at liberty to bring the experiment to an end if he has reached the physical or mental state where continuation of the experiment seems to him to be impossible.

- During the course of the experiment the scientist in charge must be prepared to terminate the experiment at any stage, if he has probable cause to believe, in the exercise of the good faith, superior skill, and careful judgment required of him, that a continuation of the experiment is likely to result in injury, disability, or death to the experimental subject.

Belmont Report

Due to ongoing atrocities, The Belmont Report was written by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Commission, created as a result of the National Research Act of 1974, was charged with identifying the basic ethical principles that should underlie the conduct of biomedical and behavioral research involving human subjects and developing guidelines to assure that such research is conducted in accordance with those principles. Informed by monthly discussions that spanned nearly four years and an intensive four days of deliberation in 1976, the Commission published the Belmont Report, which identifies basic ethical principles and guidelines that address ethical issues arising from the conduct of research with human subjects.

The basic ethical principles of the Belmont Report include:

- Respect for persons.

Respect for persons incorporates at least two ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection. The principle of respect for persons thus divides into two separate moral requirements: the requirement to acknowledge autonomy and the requirement to protect those with diminished autonomy.

- Beneficence.

Persons are treated in an ethical manner not only by respecting their decisions and protecting them from harm, but also by making efforts to secure their well-being. Such treatment falls under the principle of beneficence. The term “beneficence” is often understood to cover acts of kindness or charity that go beyond strict obligation. Two general rules have been formulated as complementary expressions of beneficent actions in this sense: (1) do not harm and (2) maximize possible benefits and minimize possible harms.

- Justice.

Who ought to receive the benefits of research and bear its burdens? This is a question of justice, in the sense of “fairness in distribution” or “what is deserved.” An injustice occurs when some benefit to which a person is entitled is denied without good reason or when some burden is imposed unduly. Another way of conceiving the principle of justice is that equals ought to be treated equally. However, this statement requires explication. Who is equal and who is unequal? What considerations justify departure from equal distribution? Almost all commentators allow that distinctions based on experience, age, deprivation, competence, merit and position do sometimes constitute criteria justifying differential treatment for certain purposes. It is necessary, then, to explain in what respects people should be treated equally. There are several widely accepted formulations of just ways to distribute burdens and benefits. Each formulation mentions some relevant property on the basis of which burdens and benefits should be distributed. These formulations are (1) to each person an equal share, (2) to each person according to individual need, (3) to each person according to individual effort, (4) to each person according to societal contribution, and (5) to each person according to merit.

Ethical Issue

Here is an example of a clinical nursing research issue and resulting ethical dilemmas.

Research Issue:

A hospital is conducting a clinical nursing study to test a new pain management protocol for terminally ill cancer patients. The study aims to evaluate whether higher doses of an experimental opioid provide better pain relief compared to standard treatments.

Potential Ethical Dilemma:

- Informed Consent & Vulnerability: Terminally ill patients may be desperate for pain relief and could feel pressured to participate, even if they don’t fully understand the risks of the experimental treatment.

- Risk vs. Benefit: The new opioid could have unknown side effects, including increased sedation or respiratory depression, potentially hastening death. Should the study proceed if risks are uncertain?

- Withdrawal from Study: If a participant wishes to withdraw, should they still be allowed to receive the experimental drug outside the study?

- Justice & Fair Access: How do researchers ensure that all eligible patients, not just those with strong advocacy or financial means, have an equal opportunity to participate?

Declaration of Helsinki

In 1964, the World Medical Association adopted what is known as the Declaration of Helsinki, in Helskini, Finland. They developed the declaration as a statement of ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, including research on identifiable human material and data.

The General Principles:

-

- The Declaration binds the physician with the words, “The health of my patient will be my first consideration,” and the International Code of Medical Ethics declares that, “A physician shall act in the patient’s best interest when providing medical care.”

- It is the duty of the physician to promote and safeguard the health, well-being and rights of patients, including those who are involved in medical research. The physician’s knowledge and conscience are dedicated to the fulfilment of this duty.

- Medical progress is based on research that ultimately must include studies involving human subjects.

- The primary purpose of medical research involving human subjects is to understand the causes, development and effects of diseases and improve preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions (methods, procedures and treatments). Even the best proven interventions must be evaluated continually through research for their safety, effectiveness, efficiency, accessibility and quality.

- Medical research is subject to ethical standards that promote and ensure respect for all human subjects and protect their health and rights.

- While the primary purpose of medical research is to generate new knowledge, this goal can never take precedence over the rights and interests of individual research subjects.

- It is the duty of physicians who are involved in medical research to protect the life, health, dignity, integrity, right to self-determination, privacy, and confidentiality of personal information of research subjects. The responsibility for the protection of research subjects must always rest with the physician or other health care professionals and never with the research subjects, even though they have given consent.

- Physicians must consider the ethical, legal and regulatory norms and standards for research involving human subjects in their own countries as well as applicable international norms and standards. No national or international ethical, legal or regulatory requirement should reduce or eliminate any of the protections for research subjects set forth in this Declaration.

- Medical research should be conducted in a manner that minimizes possible harm to the environment.

- Medical research involving human subjects must be conducted only by individuals with the appropriate ethics and scientific education, training and qualifications. Research on patients or healthy volunteers requires the supervision of a competent and appropriately qualified physician or other health care professional.

- Groups that are underrepresented in medical research should be provided appropriate access to participation in research.

- Physicians who combine medical research with medical care should involve their patients in research only to the extent that this is justified by its potential preventive, diagnostic or therapeutic value and if the physician has good reason to believe that participation in the research study will not adversely affect the health of the patients who serve as research subjects.

- Appropriate compensation and treatment for subjects who are harmed as a result of participating in research must be ensured.

The declaration goes on to cover principles of:

Risks, Burdens, and Benefits: Medical research involving human subjects may only be conducted if the importance of the objective outweighs the risks and burdens to the research subjects.

Vulnerable Groups and Individuals: All vulnerable groups and individuals should receive specifically considered protection.

Scientific Requirements and Research Protocols: Medical research involving human subjects must conform to generally accepted scientific principles, be based on a thorough knowledge of the scientific literature, other relevant sources of information, and adequate laboratory and, as appropriate, animal experimentation. The welfare of animals used for research must be respected.

Research Ethics Committees: The research protocol must be submitted for consideration, comment, guidance and approval to the concerned research ethics committee before the study begins. This committee must be transparent in its functioning, must be independent of the researcher, the sponsor and any other undue influence and must be duly qualified. It must take into consideration the laws and regulations of the country or countries in which the research is to be performed as well as applicable international norms and standards but these must not be allowed to reduce or eliminate any of the protections for research subjects set forth in this Declaration.

The committee must have the right to monitor ongoing studies. The researcher must provide monitoring information to the committee, especially information about any serious adverse events. No amendment to the protocol may be made without consideration and approval by the committee. After the end of the study, the researchers must submit a final report to the committee containing a summary of the study’s findings and conclusions.

Privacy and Confidentiality: Every precaution must be taken to protect the privacy of research subjects and the confidentiality of their personal information.

Informed Consent: Participation by individuals capable of giving informed consent as subjects in medical research must be voluntary. Although it may be appropriate to consult family members or community leaders, no individual capable of giving informed consent may be enrolled in a research study unless he or she freely agrees.

Use of Placebo: The benefits, risks, burdens and effectiveness of a new intervention must be tested against those of the best proven intervention(s), except in the following circumstances:

Where no proven intervention exists, the use of placebo, or no intervention, is acceptable; or where for compelling and scientifically sound methodological reasons the use of any intervention less effective than the best proven one, the use of placebo, or no intervention is necessary to determine the efficacy or safety of an intervention and the patients who receive any intervention less effective than the best proven one, placebo, or no intervention will not be subject to additional risks of serious or irreversible harm as a result of not receiving the best proven intervention.

Extreme care must be taken to avoid abuse of this option.

Institutional Review Board

An Institutional Review Board (IRB) approves and provides oversight of research studies and projects that involve human subjects. The primary mission of an IRB is to ensure the protection of the rights and welfare of all human participants in research. Under FDA regulations, an Institutional Review Board is group that has been formally designated to review and monitor biomedical research involving human subjects prior to a study starting. In accordance with FDA regulations, an IRB has the authority to approve, require modifications in (to secure approval), or disapprove research.

Before undertaking a study, researchers must submit research plans to an IRB and must also undergo any training that the IRB has established at a given facility or institution. We have an IRB here at Utah University, and all faculty, staff, and students must submit an IRB application if they are planning on conducting systematic research with human subjects.

With particular focus in ethical protection of human subjects is the rights of special vulnerable groups. These include:

- Children: Children do not have the competence to given informed consent, so the children’s parents or guardians must give consent. However, the children must give assent (affirmative agreement) as well.

- Mentally or emotionally disabled people: Individuals whose disability makes it impossible or difficult to obtain informed consent must have legal guardian consent.

- Severely ill or physically disabled people: For these individuals, it might be necessary to assess their ability to make reasoned decisions about study participation.

- The terminally ill: These individuals can seldom expect to personally benefit from research, so the risk/benefit ration needs to be very carefully assessed.

- Institutionalized people: These individuals may be coerced to participate with fear of jeopardizing their care or parole status. Voluntary nature of the research needs to be emphasized.

- Pregnant women: The U.S. government has issued additional requirements governing research with pregnant women and fetuses.

The IRB is guided by principles outlined in the Belmont Report (1979), which established three core ethical principles:

- Respect for Persons – Ensuring informed consent and autonomy of participants.

- Beneficence – Maximizing benefits while minimizing risks.

- Justice – Ensuring fair selection and treatment of participants.

Any research involving human subjects, personal data, or interventions must typically undergo IRB review before it can be conducted. This process ensures that participants are not exposed to unnecessary harm, that data is collected responsibly, and that research aligns with ethical standards such as those in the Common Rule (45 CFR 46), which governs human subjects research in the U.S.

The level of IRB review required for a study depends on the level of risk posed to participants. The three primary categories of IRB review are Exempt, Expedited, and Full Board Review.

- Exempt Review

Research qualifies for exempt status if it involves minimal risk to participants and falls into specific categories, such as:

-

- Anonymous surveys, interviews, or educational assessments.

- Studies using publicly available data.

- Benign behavioral interventions where subjects cannot be identified.

Even though these studies are considered “exempt” from full IRB review, researchers still submit an application for verification, and they must still adhere to ethical standards, including informed consent when appropriate.

- Expedited Review

Studies that involve minimal risk but include some form of interaction or data collection that does not qualify as exempt require expedited IRB review. These include:

-

- Studies collecting biological samples (e.g., blood draws in non-invasive amounts).

- Research involving existing medical records or physiological data collection (e.g., heart rate monitoring).

- Studies involving non-invasive behavioral testing (e.g., cognitive tasks, reaction time studies).

An expedited review is conducted by a small subset of the IRB (often one or two members) rather than the full board, which speeds up the approval process while maintaining ethical oversight.

- Full Board Review

Research that involves more than minimal risk or includes vulnerable populations (e.g., children, prisoners, individuals with cognitive impairments) requires full board review. This means the entire IRB committee meets to review and discuss the study before granting approval. Research requiring full board review may include:

-

- Clinical trials testing new drugs or medical interventions.

- Studies involving deception that could impact participants’ autonomy.

- Psychological research with potential emotional distress.

- Sensitive topics such as trauma, abuse, or illegal activity.

Because full board review is the most comprehensive and rigorous, it often takes longer than exempt or expedited reviews. However, it ensures that high-risk studies appropriately protect participants from harm. Failure to obtain proper IRB approval can have serious consequences, including:

-

- Ethical violations that harm participants.

- Legal consequences (e.g., violations of privacy laws such as HIPAA).

- Loss of funding for federally supported research.

- Retraction of published studies or damage to a researcher’s reputation.

Ultimately, the IRB serves as a gatekeeper for ethical research, ensuring that studies are designed with integrity, participant safety, and societal benefit in mind. By understanding the IRB process and the different levels of review, researchers can conduct studies that advance knowledge while upholding the highest ethical standards.

Ponder This

If a study has the potential to yield groundbreaking scientific discoveries but poses minimal yet unavoidable risks to participants, how should researchers balance the pursuit of knowledge with ethical responsibility?

Ethical Issue

Here is an example of a clinical nursing research issue and resulting ethical dilemmas.

Research Issue:

A nursing research team is investigating how different communication styles affect patient anxiety levels before surgery. To study the effects of emotional reassurance vs. clinical explanation, nurses are instructed to alter their approach when speaking with patients but patients are not told they are part of a study until after surgery.

Potential Ethical Dilemma:

Deception vs. Autonomy: Is it ethical to withhold information from patients about their participation in research? Should deception be allowed if it prevents bias in responses?

- Psychological Harm: If patients later learn they were unknowingly involved in a study, they may feel manipulated or violated. How can researchers ensure that the post-study debriefing process repairs trust?

- Informed Consent: Since patients can’t give prior consent, is retrospective consent (after surgery) ethically acceptable?

- Patient Safety: What if the altered communication style increases patient anxiety rather than reducing it? Would the study be responsible for any negative psychological outcomes?

Ethical Principles and Protecting Study Participants

In addition to applying to an IRB, the researcher must also have procedures in place to protect human subjects from risk of harm.

One strategy that helps to minimize this risk is to do a risk/benefit assessment. With this assessment, researchers evaluate whether the benefits of participating in a study are in line with the potential risks. A risk-benefit assessment in research is a crucial process used to evaluate the potential risks and benefits associated with a study. This assessment helps researchers, ethics committees, and institutional review boards (IRBs) determine whether the anticipated benefits of the research justify the risks to participants. Here’s a breakdown of what this entails:

Identifying Risks

- Physical Risks: Potential harm to participants’ physical health, such as side effects from a new drug or injury from a procedure.

- Psychological Risks: Emotional or mental distress, such as anxiety or discomfort caused by sensitive questions or interventions.

- Social Risks: Potential for social harm, such as stigmatization or breaches of confidentiality that could affect participants’ social standing or relationships.

- Economic Risks: Financial burdens on participants, such as costs of participating in the study or loss of income due to time away from work.

- Legal Risks: Possibility of legal repercussions for participants, such as disclosure of illegal activities.

Identifying Benefits

- Direct Benefits to Participants: Any positive outcomes that participants might experience as a result of their involvement in the study, such as improved health or access to new treatments.

- Indirect Benefits: Broader benefits that may not directly impact the participants but could benefit society, such as advancements in medical knowledge, development of new treatments, or improvements in public health.

Weighing Risks and Benefits

- The assessment involves comparing the severity and likelihood of the risks against the magnitude and likelihood of the benefits. This process helps determine if the study is ethically justifiable.

- A study may be deemed acceptable if the benefits significantly outweigh the risks, especially if the research has the potential to lead to significant advancements in knowledge or treatment.

Minimizing Risks

- Researchers are responsible for taking steps to minimize risks wherever possible. This includes implementing safety measures, ensuring confidentiality, and providing participants with clear information about the potential risks and benefits before they consent to participate.

Informed Consent

- The risk-benefit assessment is a key component of the informed consent process. Participants must be fully aware of the risks and benefits before agreeing to take part in the research, ensuring that their participation is voluntary and informed.

A risk-benefit assessment is an essential part of ethical research practice, ensuring that the potential benefits of a study are sufficient to justify any risks to participants. It safeguards the well-being of participants and upholds the integrity of the research process.

Figure Above: Risk-Benefit Assessment, https://ohrpp.research.ucla.edu/assessing-risks/

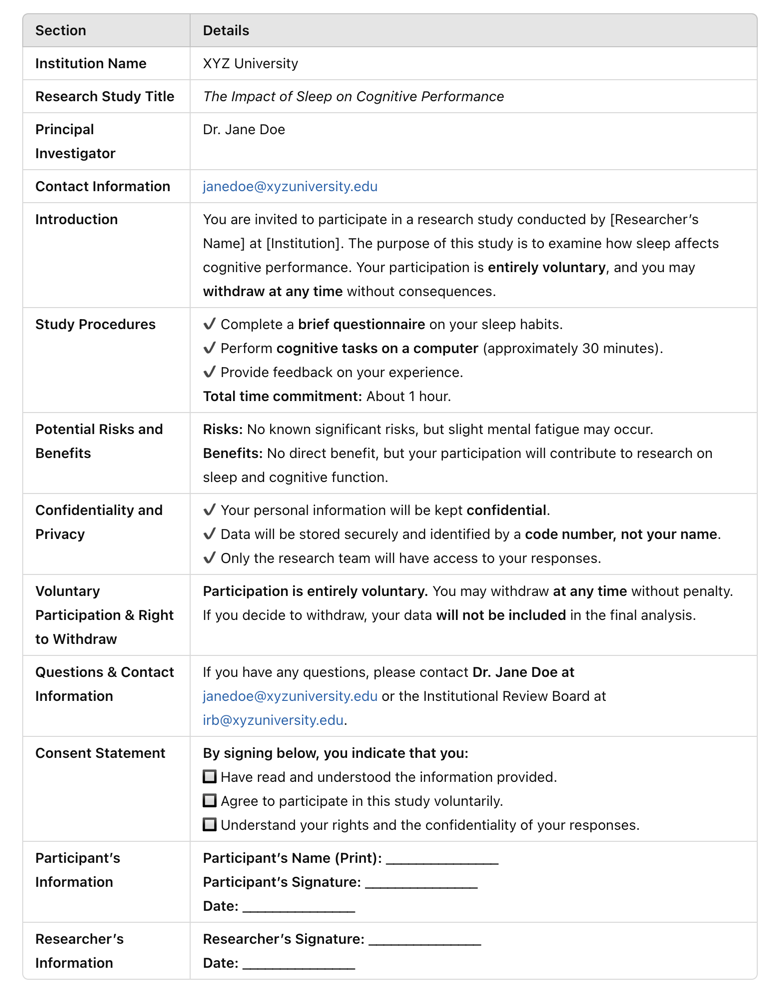

As above, another important method for safeguarding research participants is to obtain an informed consent. In an informed consent, the study is explained in simple terms, with explanations of their power of free choice. The consent contains information about the study purpose, sometimes a description of complications in prior research, specific expectations of the participation, potential costs, any benefits, the voluntary nature, and who to contact for more information, if needed.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is a foundational ethical requirement in research involving human participants. It is a process that ensures participants are fully aware of the study’s nature, purpose, risks, benefits, and their rights before agreeing to participate. The principle of informed consent is rooted in the ethical tenets of respect for persons, autonomy, and the right to make an informed decision about one’s participation in research activities.

Key Components of Informed Consent

Disclosure: The Right to Full Disclosure is the absence of deception or concealment. The “right to full disclosure” is a legal and ethical principle that mandates parties involved in specific situations to share all relevant information to ensure fairness, transparency, and informed decision-making. Researchers must provide comprehensive information about the study, including its purpose, duration, procedures, potential risks and benefits, and the extent of confidentiality. Participants should be informed about any possible discomforts, alternative procedures or treatments (if applicable), and whom to contact for questions regarding the study or their rights as participants.

Comprehension: It is not enough to simply disclose information; participants must also understand it. Researchers have a duty to present information in a clear and accessible manner, avoiding complex jargon or technical terms that could confuse participants. Special considerations must be taken when working with vulnerable populations, such as children, individuals with cognitive impairments, or those with limited literacy, ensuring that the consent process is adapted to their level of understanding.

Voluntariness: Participation in research must be voluntary, without any form of coercion or undue influence. Participants should know that they have the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty or loss of benefits to which they are otherwise entitled. This voluntariness is critical to upholding the autonomy of participants.

Capacity: The ability of participants to give informed consent depends on their capacity to understand the information provided and make an informed decision. Researchers must assess the capacity of participants, particularly when dealing with minors, the elderly, or individuals with mental health conditions. When participants lack capacity, consent must be obtained from a legally authorized representative.

Documentation: In most cases, participants sign a written informed consent form. However, in certain minimal-risk studies (e.g., anonymous online surveys), verbal or implied consent may be sufficient.

For vulnerable populations (e.g., children, individuals with cognitive impairments), additional safeguards such as obtaining parental consent or legal guardian approval are required.

Image Above: Example of Informed Consent

Process of Obtaining Informed Consent

The informed consent process typically involves several steps:

Presentation of Information: Researchers present participants with a consent form or information sheet detailing all relevant aspects of the study. This document should be written in a language that is easy to understand and appropriate for the participant’s reading level.

Discussion: An open dialogue between the researcher and participant allows for questions to be asked and clarifications to be made. This interaction is crucial for ensuring that the participant truly understands the study and what their involvement entails.

Documentation: Participants indicate their agreement to participate by signing the consent form. However, documentation of consent can take various forms, including written, electronic, or verbal, depending on the nature of the study and the participant’s needs.

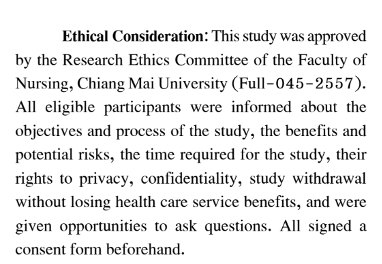

Above Image: Example of Research Ethics Committee Approval (much like an IRB) within a published research article (Pankong et al., 2018).

Special Considerations and Ethical Challenges

In some research contexts, obtaining informed consent can present ethical challenges. For instance, in emergency research or studies involving populations with impaired decision-making abilities, traditional consent processes may not be feasible. In such cases, alternative consent processes, such as deferred consent or obtaining consent from a legally authorized representative, are used to ensure ethical standards are met while balancing the practical constraints of the study.

In some situations, consent is implied. For example, if a nursing instructor were to walk into a classroom and explain that they are conducting a survey for research, and then hand the survey out to whomever wants it, it is implied consent if you proceed to fill the survey out.

Study participants also have the right to keep their information private and in strict confidence. A participant’s right to privacy is protected. Anonymity is the most secure means of protecting confidentiality. This occurs when the researchers cannot link the data to the individual. For example, if in the above example, you filled out the survey and it did not contain your name, birthdate, or any other identifying information, it would be anonymous. The researcher would not know who filled out each survey.

Sometimes there is confidentiality in the absence of anonymity. A promise of confidentiality is given to the participant that even though the researcher may have some private information about them (e.g. birth data, name, etc.), the information will be secured in locked files, substituting identification numbers for names, and reporting only on aggregate data for groups of participants.

| Concept | Definition | Example |

| Confidentiality | The research team protects participants’ data and identify from unauthorized disclosure. | A researcher stores survey responses using coded participant numbers instead of names. |

| Privacy | The participant’s control over what personal information is shared and with whom. | A patient decides whether to participate in a study about their mental health history. |

Strategies to Protect Confidentiality

Anonymization: Removing or encrypting identifying information (e.g., names, birthdates) from research records.

- Data Encryption: Storing electronic data securely using password protection and encryption software.

- Secure Storage: Keeping paper records in locked cabinets and digital files in secured servers.

- Limited Access: Restricting data access to only authorized researchers.

- De-identification Techniques: Replacing personal details with unique participant codes.

- Data Sharing Agreements: Establishing clear rules about who can access data and under what conditions.

Sensitive Research Considerations

Medical Research: Ensuring compliance with HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) in studies involving patient health records.

- Psychological Research: Taking precautions when collecting mental health data to prevent breaches of confidentiality.

- Social Science Research: Protecting politically sensitive or stigmatized populations (e.g., LGBTQ+ studies, addiction research).

![]() Hot Tip! Always prioritize obtaining informed consent and maintaining participant confidentiality in research. These ethical practices not only protect participants’ rights but also enhance the integrity and credibility of your study.

Hot Tip! Always prioritize obtaining informed consent and maintaining participant confidentiality in research. These ethical practices not only protect participants’ rights but also enhance the integrity and credibility of your study.

Debriefing

Finally, an important concept to also note is debriefing. Once a study is completed, researchers may conduct a debriefing session to explain the true nature of the research, particularly if deception or incomplete disclosure was used. Debriefing ensures that participants leave the study fully informed and without psychological distress. Debriefing sessions are sometimes advisable to have following data collection so that participants can ask questions or share concerns. It is up to the researchers whether they decide to share study findings with the participants after data has been analyzed, but this is a good practice to have if it is reasonable to do so. Often, it is disclosed on the informed consent whether or not the researcher will be debriefing with the participant after the study is concluded.

![]() Hot Tip! Always conduct debriefing immediately after participation to ensure that participants fully understand the study, address any concerns, and leave without distress or confusion.

Hot Tip! Always conduct debriefing immediately after participation to ensure that participants fully understand the study, address any concerns, and leave without distress or confusion.

In summary, it is vital for nurses and healthcare providers to be knowledgeable about research ethics. Be alert to vulnerable patients and ensure that their rights are upheld. It is everyone’s position and role to advocate for the ethical rights of all people. Informed consent is not a one-time event but an ongoing process throughout a participant’s involvement in the research. Researchers must continue to provide updates on new findings, changes in study procedures, or emerging risks that could affect a participant’s decision to remain in the study. Upholding the principles of informed consent is essential for maintaining trust, protecting participants, and ensuring the ethical integrity of research.

Summary Points

- Ethics are fundamental in ensuring research is conducted with integrity, respect, and responsibility.

- Ethical considerations protect participants’ rights and well-being and maintain the credibility of the nursing profession.

- Morals are beliefs about right and wrong, influenced by cultural, societal, and religious norms.

- Values are personal principles that guide individual choices and actions based on what is important to them.

- Ethics are systematic rules governing behavior, often established by professional bodies.

- Autonomy: Participants have the right to make their own decisions, supported by informed consent.

- Beneficence: Researchers are obligated to promote good and prevent harm, ensuring studies maximize benefits.

- Nonmaleficence: The principle of “do no harm,” requiring researchers to avoid causing harm to participants.

- Veracity: Commitment to truthfulness, providing participants with accurate and complete information.

- Justice: Fairness in the distribution of research benefits and burdens, ensuring equitable treatment of all participants.

- Fidelity: Maintaining trust by upholding commitments and ensuring the integrity of the research process.

- Nazi Experiments highlighted the need for ethical guidelines due to the atrocities committed during World War II.

- Tuskegee Syphilis Study was a significant ethical violation where treatment was withheld from participants, leading to changes in research practices.

- Nuremberg Code and Belmont Report established foundational ethical principles and guidelines for conducting research with human subjects.

- An IRB approves and oversees research involving human subjects to protect their rights and welfare.

- Special protections are required for vulnerable populations, such as children, the mentally disabled, and pregnant women.

- A risk-benefit assessment is a process to evaluate whether the benefits of a study justify the risks to participants which includes identifying and minimizing risks, weighing them against the potential benefits, and ensuring participants are fully informed.

- An informed consent is a key ethical practice where participants are provided with clear, understandable information about the study, ensuring voluntary and informed participation. Includes details about the study’s purpose, expectations, risks, benefits, and the right to withdraw.

- Participants’ privacy must be protected, with steps taken to maintain confidentiality and, where possible, anonymity.

- When reviewing research, consider the ethical safeguards in place, such as IRB approval, informed consent, and protection of vulnerable groups.

- Ethical vigilance is crucial for nurses and healthcare providers to advocate for the rights of all participants in research.

![]() Critical Appraisal! Ethical Components:

Critical Appraisal! Ethical Components:

- Was the study approved and monitored by an Institutional Review Board, Research Ethics Board, or other similar ethics review committee?

- Were study participants subjected to any physical harm, discomfort, or psychological distress? Did the researchers take appropriate steps to remove or prevent harm?

- Did the benefits to participants outweigh any potential risks or actual discomfort they experienced? Did the benefits to society outweigh the costs to participants?

- Was any type of coercion or undue influence used to recruit participants? Did they have the right to refuse to participate or to withdraw without penalty?

- Were participants deceived in any way? Were they fully aware of participating in a study, and did they understand the purpose and nature of the research?

- Were appropriate informed consent procedures used with participants? If not, was there a justifiable rationale?

- Were adequate steps taken to safeguard participants’ privacy? How was confidentiality maintained? Was a Certificate of Confidentiality obtained—and, if not, should one have been obtained?

- Were vulnerable groups involved in the research? If yes, were special precautions instituted because of their vulnerable status?

- Were groups omitted from the inquiry without a justifiable rationale, such as women (or men), or minorities?

Case Study: The Challenge of Reporting Adverse Events

Sarah, a newly graduated nurse, has recently joined a research team at a large urban hospital. The team is conducting a study on a new medication designed to reduce the symptoms of chronic pain in elderly patients. As part of her role, Sarah is responsible for monitoring the participants and recording any adverse events that occur during the study.

During one of her shifts, Sarah notices that several participants have reported experiencing dizziness and nausea after taking the medication. While these symptoms are not life-threatening, they are significant enough to interfere with the participants’ daily activities. Sarah brings her concerns to Dr. Jones, the lead researcher, who reassures her that mild side effects were anticipated and are not unusual in early-stage trials. He advises her to continue monitoring but suggests that these events do not need to be formally reported to the ethics committee at this stage.

Sarah feels conflicted. She understands that Dr. Jones has more experience in research and values his guidance. However, she is also aware that her duty as a nurse is to advocate for the well-being of the patients involved in the study. Sarah is concerned that by not reporting these adverse events, the research team might be overlooking important data that could impact the participants’ safety and the integrity of the study.

Over the next few days, the symptoms persist in a few more participants, prompting Sarah to review the study’s ethical guidelines. She discovers that even mild adverse events should be reported if they are consistent and affect a significant number of participants. With this information, Sarah decides to approach Dr. Jones again, this time with a stronger conviction. She expresses her concerns and presents the guidelines she found.

After a thoughtful discussion, Dr. Jones agrees with Sarah’s assessment. He acknowledges that the research team should have reported the adverse events earlier and takes immediate steps to inform the ethics committee and adjust the study protocol. The reporting leads to a temporary halt in the study while the data is reviewed and the medication is further evaluated.

Conclusion: Sarah’s actions ensured that the participants’ safety was prioritized, demonstrating the critical role of vigilance and ethical responsibility in nursing research. This scenario highlights the importance of nurses’ advocacy in research settings, especially when it comes to reporting adverse events. By following ethical guidelines and trusting her professional judgment, Sarah helped protect the integrity of the study and the well-being of the participants, reinforcing the principle that patient safety should always come first in research.

Ponder This

Imagine you are a nurse working in a community health clinic that serves a diverse and often vulnerable population. You have been approached by a research team from a local university that is conducting a study on the effectiveness of a new educational program aimed at improving diabetes management among low-income patients. The program requires participants to attend weekly sessions for six months, during which they will receive education and support for managing their condition.

As both a nurse and a trusted caregiver in the community, you are excited about the potential benefits this study could bring to your patients. You believe the educational program could significantly improve their health outcomes. However, the research team has asked you to help recruit participants from your clinic. They suggest that because you have established relationships with the patients, your encouragement might persuade them to join the study.

You find yourself in a challenging situation. On one hand, you want to support the research and believe in its potential benefits. On the other hand, you are concerned about the ethical implications of your dual role as both a caregiver and a recruiter for the study. You worry that patients might feel pressured to participate because of their trust in you, and you question whether this could affect their ability to provide truly informed consent. Additionally, you consider whether your involvement in the research could compromise the quality of care you provide if your patients feel you are prioritizing the study over their individual needs.

As you navigate this scenario, consider the ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, and fidelity. Reflect on how you can balance your commitment to providing high-quality care with your interest in advancing nursing research, while ensuring that your patients’ rights and well-being remain at the forefront of your practice.

References & Attribution

“Green check mark” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

“Magnifying glass” by rawpixel licensed CC0

American Nurses Association (ANA). (2015). Code of ethics for nurses. http://www.nursingworld.org/codeofethics

Born, S. L., & Preston, J. J. (2016). The fertility problem inventory and infertility-related stress: A case study. The Qualitative Report, 21(3), 497-520. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2307

Burkhardt, M. A., & Nathaniel, A. K. (2014). Ethics and issues in contemporary nursing (4th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). The U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/index.html

Pankong, O., Pothiban, L., Sucamvang, K., Khampolsiri, T. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of enhancing positive aspects of caregiving in Thai dementia caregivers for dementia. Pacific Rim Internal Journal of Nursing Res, 22(2), 131-143.

Resnick, D. B. (2020). What is ethics in research and why is it important? National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/resources/bioethics/whatis/index.cfm

Roelcke, V. (2004). Nazi medicine and research on human beings. The Lancet, 364, 6-7.

Salgueiro-Oliveira, A., Parreira, P., & Veiga, P. (2012). Incidence of phlebitis in patients with peripheral intravenous catheters: The influence of some risk factors. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 30(2), 32.