The Foundations of Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing

In this module, we will begin to learn about evidence-based practice, why it is important in what we do as nurses, and the purpose of evidence-based practice in nursing.

Content includes:

- Research and the Evidence Produced

- Components of Evidence-Based Practice

- The Purposes of Research

- The Need for Research in Nursing and Nursing Education

- Understanding the Nurse’s Role in EBP

- The Gap in Utilizing Best Evidence in Practice

- Quality Improvement and Research Utilization

- Conceptual Frameworks

Objectives:

- Explain why evidence-based practice is needed in nursing

- Describe alternative sources of “Why we do what we do” [anecdotal evidence]

- Describe “evidence-based practice” in nursing

- Explain the purposes of evidence-based practice in nursing

- Describe conceptual frameworks

- Differentiate quality improvement and research utilization

Key Terms:

Empirical Evidence: Evidence that is obtained through experiments or observation and gathered through the senses.

External Evidence: Evidence from scientific literature—particularly the results, data, statistical analysis, and conclusions of a study. Systematic reviews and other research methodologies are a examples of external evidence.

Internal Evidence: Data collected through experience accumulated from daily practice, knowledge from formal education, and specific experience gained from interactions.

Evidence: The available body of facts or information that supports a proposition or that is believed to be true.

Evidence-Based Practice: A collective effort of applied or translated research findings into clinical care practices and clinical decision-making.

Nursing Research: Development of new knowledge about health, health promotion, care of persons and communities, and nursing actions that support best clinical care.

Research: Creation of new knowledge from a systematic approach to investigate a behavior or theory or to understand a phenomenon.

Research Utilization: The application of selected facets of a scientific analysis through a process unconnected to the fundamental research.

Quality Improvement: A process utilized to investigate a policy, procedure, or protocol to determine if it addresses an aspect identified through an evidence-based practice process and works to validate current practice.

Scientific Method: The specific steps to define the activities to acquire new knowledge through observation and answering questions, rigorous interpretation about what is observed.

Systematic: A fixed plan, steps, or approach to methodically complete an activity.

Triad of EBP: A conscientious use of improving clinical outcomes to include: Best available evidence, patient values and expectations, and clinical expertise.

Introduction

The main tenant of nursing is to provide high-quality care for all patients, considering their social, financial, cultural, and individual needs – a holistic, person-centered approach. This is tied to the social determinants of health identified by Healthy People 2030, such as economic stability, education, social and community context, health and healthcare, and neighborhood and environment (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2030). These areas offer opportunities for research, quality improvement, and evidence-based practice (EBP) projects.

Think about the moment you first meet a patient. Ideally, they should feel confident that your care is safe, accurate, and based on the latest health information. And, that information should come from the latest research. While research provides the foundation, quality improvement activities and personal expertise help determine best practices. Tailoring this information to each patient’s unique needs is also essential. The nurse and the patient must agree together that the proposed treatment or modality is necessary. This integrates the patient’s preferences and values alongside the nurse’s expertise and EBP knowledge.

After determining the essential requirements for care, the nurse must thoughtfully and carefully apply evidence-based knowledge to each patient’s unique situation. This involves considering the patient’s specific needs, health expectations, and other relevant factors and adapting the evidence accordingly. Therefore, the foundation of nursing care should be based on research-tested, research-confirmed, and critically analyzed information while also considering the unique characteristics of each patient and their situation.

What is Evidence-Based Practice?

Before we dive deeper into understanding the implications of evidence-based practice, let’s start by defining it in a way that makes sense. Evidence-based practice (EBP) is like being a detective in a white coat—it’s all about making the best decisions for your patients by using the most reliable clues (or evidence) available. Imagine if Sherlock Holmes decided to solve his cases by guessing instead of investigating; things wouldn’t turn out so great, right?

In nursing, evidence-based practice means you’re not just going with your gut or what your friend in the breakroom said last week. Instead, you’re using the latest research (the solid, fact-checked stuff), your own clinical skills, and considering what your patient wants. It’s like putting together the perfect smoothie: a mix of research (fruits), clinical know-how (yogurt), and patient preferences (a sprinkle of chocolate chips). The goal is to ensure you’re giving care that’s supported with evidence and shown to work and, as a nice byproduct, makes you feel like the rockstar nurse you’re becoming!

Let’s learn the definition of evidence-based practice (EBP): The act of basing practice on best evidence to make patient care decisions to improve outcomes and being cost effective.

EBP is a broad concept referring to the incorporation of current, valid, and relevant external evidence during the decision-making process. In the health sciences, such evidence is most commonly found in current high-quality research studies such as systematic reviews that can be applied to the specific patient, group, or population being considered.

Alright, now that we have a basic description of evidence-based practice (EBP) and know what it is, let’s talk about why it is such a big deal in nursing and then work on understanding more about it and then work on applying it to your current clinical practice as a nursing student.

Why Evidence-Based Practice Matters

Providing quality care means using the best and latest research. Malloch and Porter-O’Grady (2015) emphasize that nurses need to apply up-to-date research in their daily practice. This means using reliable clinical knowledge and information to ensure high-quality care. Regardless of what we call it – best practices, EBP, or quality of care – the foundation of nursing must be based on solid evidence.

Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt (2019) explain that healthcare providers should know how to find, analyze, and use relevant evidence. This ensures patients trust that their care is based on the best available evidence. Nurses should avoid anecdotal treatments and instead rely on evidence-based practices.

EBP in nursing has at its core concept, improving health care outcomes. In addition to improving outcomes, it is also concerned about keeping costs down.

Let’s think about this for a second. Let’s say we discover an awesome new pharmaceutical that eliminates insulin-resistant diabetes, but that same medication costs $29,990.00 per weekly dose and it must be taken for life. Would this be cost effective? It seems not, but perhaps it is more cost effective than all the ramifications that come from diabetes. This is considered when we look at efficacy of a new treatment. So, while we could improve health care outcomes with this new medication, it may or may not be cost effective to do so.

Major Developments of EBP in Healthcare & Nursing

The development of Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) in healthcare and nursing has transformed how care is delivered, shifting the focus toward integrating the best available research with clinical expertise and patient preferences. Major milestones, such as implementing the Affordable Care Act (ACA), have emphasized the importance of EBP in improving patient outcomes and reducing costs. Changes in nursing education have further reinforced the need for nurses to be proficient in EBP, equipping them with the skills to critically appraise and apply research in their daily practice. Additionally, the influential “Future of Nursing” report has charted a course for the profession, advocating for higher education, expanded roles, and a commitment to EBP to meet the evolving needs of the healthcare landscape. These developments highlight the growing prominence of EBP in nursing and underscore its vital role in shaping a more effective, patient-centered healthcare system.

- The Affordable Care Act (ACA)

In 2010, the ACA was introduced to make healthcare more affordable and accessible. It emphasizes research to ensure safe, quality patient care. The ACA has driven changes in reducing hospital readmissions and improving care quality. Nurses are now taking on more roles in community health and preventive care. The focus on value-based care means every intervention is scrutinized for effectiveness and efficiency. Nurses must adopt best practices in outpatient settings more frequently.

- Changes in Nursing Education

Also, in 2010, the Carnegie Foundation called for major changes in nursing education. They recommended that nurses be trained in research and EBP (Benner, Sutphen, Leonard, & Day, 2010). Advances in technology and the COVID-19 pandemic further transformed nursing education. It’s crucial for nursing programs to ensure graduates understand and use EBP in their practice.

- The Future of Nursing Report

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) highlighted the importance of interdisciplinary projects and innovation in nursing (National Academy of Sciences, 2020). The American Nurses Association (ANA) built on this, urging nurses to address social determinants of health and support community resilience. Although the goal of having 90% of clinical decisions based on evidence by 2020 wasn’t met, it remains a driving force in healthcare. The IOM identified priorities such as improving access to care, transforming nursing education, and promoting leadership.

Changes in nursing care are happening every day. New studies are being conducted that change the best evidence available in some cases. So, to further the point of why EBP is important in nursing, let’s think about why we do what we do in patient care. How many times have you read one method to perform a skill in a textbook, but yet an instructor tells you something different, and then you might even see it done a different way in clinical. Why is that? Well, there are a few reasons for that and we will explore those in a bit. Let’s look at another scenario, first.

In the early 1900’s, it was thought that flowers should never be placed in a hospital room because they would consume much-needed oxygen and rob it from the patient. In fact, during a recent orientation at a hospital on the evening shift, the nurse preceptor explained to the orienting nurse that every evening at 9 pm, all flowers and plants are removed from the patient rooms and stored until the following day. The nurse preceptor explained that “this is the way we have always done it here.” This act was based on fallacies and inaccurate science. In fact, this error in thinking traces back to 1923 in print form and spread by word of mouth from there. In a study published in International Archives of Occupation and Environmental Health (1977), the author reported that plants altered oxygen and CO2 levels by about 1.5% – a very negligible amount (Gale, Redner-Carmi, & Gale, 1977). When you consider that a human being, such as the person in the bed in the hospital room, uses up about 2.5 cubic feet (71 liters) of oxygen in an hour, while a pound of foliage sucks up about 0.026 gallons (0.1 liters) in that same time period, it would make far more sense to ban oxygen-sucking visitors than to ban flowers! Additionally, Park and Mattson (2009) studying therapeutic influences of plants in hospital rooms, reported that, “Patients in hospital rooms with plants and flowers had significantly shorter hospitalizations, fewer intakes of analgesics, lower ratings of pain, anxiety, and fatigue, and more positive feelings and higher satisfaction about their rooms when compared with patients in the control group.” It seems that patients benefit from having flowers in their rooms.

The Students’ Role with EBP

Some students get to this point and wonder, “But, why do we need to know this in a nursing program? We aren’t nurses yet!”

Well, let’s dive into that briefly. As a nursing program, we adhere to the standards by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). AACN has specific essentials that various levels of competencies that nursing students should meet by the time they graduate. If you would like to take a look at these, navigate to this website: https://www.aacnnursing.org/Essentials

Here are the competencies that AACN clearly outlines to the entry-level nursing student (that’s us!) to achieve as they relate specifically to evidence and EBP:

- Evaluate clinical practice to generate questions to improve nursing care.

- Evaluate appropriateness and strength of the evidence.

- Use best evidence in practice.

- Participate in the implementation of a practice change to improve nursing care.

- Participate in the evaluation of outcomes and their implications for practice.

- Explain the rationale for ethical research guidelines, including Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines.

- Demonstrate ethical behaviors in scholarly projects including quality improvement and EBP initiatives.

- Advocate for the protection of participants in the conduct of scholarly initiatives.

- Recognize the impact of equity issues in research.

Stated by the AACN:

“Knowledge of the basic principles of the research process, including the ability to critique research and determine its applicability to nursing’s body of knowledge, is critical. Ethical comportment in the conduct and dissemination of research and advocacy for human subjects are essential components of nursing’s role in the process of improving health and health care. Whereas the research process is the generation of new knowledge, evidence-based practice (EBP) is the process for the application, translation, and implementation of best evidence into clinical decision-making. While evidence may emerge from research, EBP extends beyond just data to include patient preferences and values as well as clinical expertise. Nurses, as innovators and leaders within the interprofessional team, use the uniqueness of nursing in nurse-patient relationships to provide optimal care and address health inequities, structural racism, and systemic inequity” (AACN, 2021).

If you proceed on to a graduate-level program, these competencies level up a bit to a higher standard. The Essentials are a direct analogy of “Why we do what we do” at the nursing department curriculum development level. They also guide our development of courses. This EBP course is not a course grabbed out of thin air just to subject some maddening frustration upon you. BSN programs nationwide have some type of EBP course just like this one. Some have their students develop scholarly, evidence-based papers and some have their students develop EBP projects or posters like this course. They all have the same goal: To create a better understanding of how to read published evidence, how to utilize that evidence in practice, and how to improve patient outcomes with the best available evidence.

Undergraduate nursing students are also charged with gaining a higher level of critical thinking. This means making fewer assumptions based on hidden fallacies and also examining the status quo. Critical thinking is a purposeful, self-regulatory judgment that interprets analysis, evidence, and methodology when seeking a decision. Critical thinking means the provider should consistently evaluate how much to trust the findings of a given research study. It is a thinking skill consisting of the evaluation of arguments. In the United States and in other countries, research plays an important role in nurses’ credentialing and status. In particular, research and efforts to promote evidence-based practice are key elements of the Magnet recognition program. Changes to nursing practice now occur regularly because of EBP efforts, and these efforts enhance the status of the profession.

An emerging trend in health care research is a focus on patient-centeredness and the degree to which evidence applies to individual patients, small groups of patients, and local contexts. Attending to the applicability of research findings is likely to become an increasingly important goal for nurses pursuing an evidence-based practice.

Current Practice Decisions

Before we can really understand some of the alternative sources of “what we do”, let’s look at the timeline of conducting a research study and how long it may take to get the results of that study into practice. There is a standard refrain of “17 years to move evidence into practice” and indeed there is a long gap that prevents amazing research from being embedded (if ever) into clinical practice (IOM, 2001).

Timeline of evidence into clinical practice:

- Testable idea must be formulated and refined.

- Research team must be assembled.

- Preliminary data gathered.

- Permissions must be obtained.

- Regulatory requirements must be met.

- Support must be obtained, including personnel, supplies, and funding.

- Subjects must be enrolled.

- Interventions must be delivered.

- Data must be collected.

- Analyses performed.

- Dissemination (sharing) of data through presentations and publications.

- Then, and maybe then, practitioners and/or facilities investigate embedding this into practice.

- Assessment must be completed to see if these changes are working/not working.

- And so on.

Moving research into practice is a delicate balance of incorporating new findings quickly enough to maximally benefit patients, but not so quickly that we expose patients to unnecessary harm (Munro & Savel, 2016).

We now see that there can be a very long process to embed latest/most current, best evidence into practice. In the meantime, this lack of embedding best evidence in clinical practice may be harming the efforts to improve clinical outcomes. If clinicians are just doing “what we’ve always done”, and we are not using the best evidence that is out there, this creates an issue.

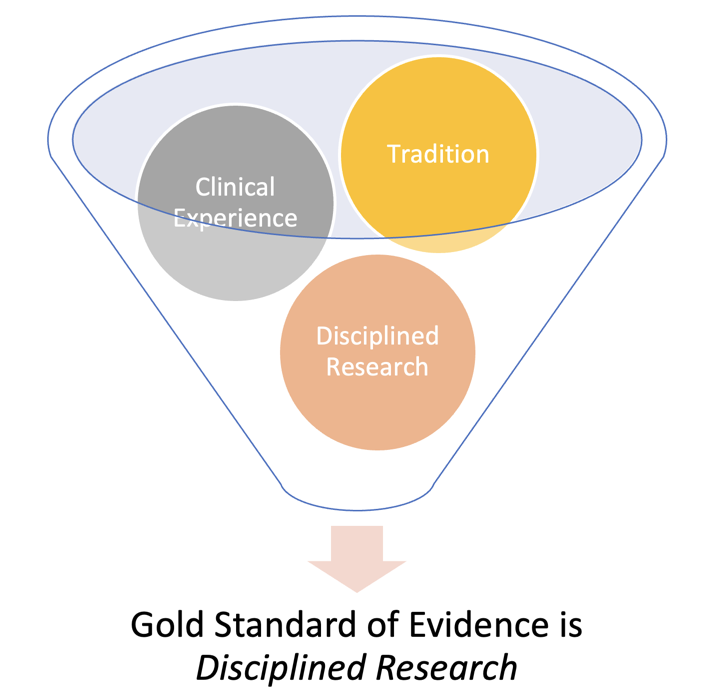

Some sources of evidence for our current clinical practice may be:

- Tradition and authority/ “experts”

- Change is difficult. Many nursing decisions are based on history. We just do what we’ve always done. No one has rocked the boat. Things seem alright, why change?

- Anecdotally, things sometimes just “work”. However, sometimes our actions are based on false assumptions, untrue facts, and unreliable personal accounts. How much of what we do is based on anecdotal evidence? Think about this a bit. Think of every skill you’ve learned in nursing school so far. Is there evidence to support it? Or, are you simply doing what someone has taught you and you have relied on their authority and expertise? How do you know if it is the best method that is rooted in scientific evidence?

- There is what is considered a “unit culture”. Many decisions are made based on tradition or the guidance of an authority. These types of knowledge are so much a part of a common heritage that few people challenge their efficacy or seek verification. Such “sacred cows” are widely used to guide practice, but they are a weaker form of knowledge than disciplined research.

- Standards persist. Here’s an example: It is no longer best evidence to perform an air bolus with an auscultation test to ensure placement of a nasogastric tube. Best evidence supports obtaining a pH and then a chest radiograph to confirm placement (AACN, 2016). We discovered this about 12 years ago! Yet, there are still textbooks, clinicians, instructors, manuals, websites, and institutional policies that support the air bolus method of placement confirmation. A 2015 study showed that more than 88% of nurses were currently using nonevidence-based practices to verify NGT placement, creating a serious patient safety issue (Relias Media, 2015).

- It is often difficult to challenge an expert. Reliance on experts and mentors is unavoidable and their information is often unchallenged.

- Lastly, it takes time to look up best evidence. The easy way out is to just do what we’ve always done. Yikes! Did you know that it used to be standard to use heat lamps to dry up wounds? Someone somewhere finally asked, “Is this really the best way to treat wounds?” and now we have evidence from research that points us to moist dressings. Heat lamps? Really? Yes – we did that. Oh my, how far we have come. But, we have to keep looking at the latest evidence. Who knows… maybe future research will tell us that dressings of bananas and chia seeds is best for wounds. Doubtful, but one never knows! We have to continually keep seeking more evidence with everything we do.

- Clinical experience

- This is a functional source of knowledge, right? Experience (expertise) is even a component of the EBP triad (we will learn that in a bit). However, it has limitations because every nurse’s experience is different than the next nurse. This makes the overall pool of experience a bit narrow and often somewhat biased as each individual comes to the proverbial table with a different outlook, experience, opinion, or background.

- Disciplined research: Here we are with the gold standard upon which we should strive to base our clinical practice. Discipline research produces scientific evidence. However, we cannot forget that nursing is not just “science” but a blend of our personality, caring, and art. Researchers generate new evidence through rigorous research. EBP provides clinicians with the processes and tools to translate that collected evidence into clinical practice to improve the quality of care and patient outcomes.

Research and the Evidence Produced

The following section explores the role of research in nursing, specifically how it contributes to the evidence base for nursing practice. Research in nursing is multifaceted, ranging from clinical trials assessing new treatments to qualitative studies that help to understand a patient’s experience. The evidence produced from research is crucial for informing nursing practice and ensuring that what clinicians do in practice is current, effective, practical, and cost-effective.

You may still be wondering why you are having to learn about research. Sometimes, it is hard to convince undergraduate nursing students of the importance of learning about research and evidence-based practice. Nursing educators see the folded arms in class and the sleepy eyes when teaching research. However, research knowledge will help you become an excellent nurse and nurse leader. If a nursing intervention is not based on the best research evidence, there is no way to determine if that intervention is the best one. Are we doing this intervention because it was taught to you, or maybe because you see everyone else doing it? As we progress through this book, you should be challenged to question every intervention you perform or see performed. This textbook aims to explain evidence-based practice and why it is a big deal in nursing. Then, you can apply this understanding to your current clinical practice as a nursing student and nurse.

Whether you realize it or not, you have already done a fair bit of research in your life. Whenever you check out Yelp reviews for a restaurant, scroll the internet for the best price on a plane fare, or explore which dog breed might be best for your lifestyle, you start with a question for which you can collect information. As you collect the information, you might start wondering how to pick the most appropriate answer for yourself as you filter through the various articles and opinions you may find. At some point, you may conclude based on your best educated guess as to which information has some validity.

Questions arise in the care of our patients as well:

- Why do we do what we do as nurses?

- Why do we assess a patient a certain way?

- Why do we clean the skin before performing an intravenous puncture?

- Does raising the head of the bed to 45 degrees versus 30 degrees make a difference for someone short of breath?

- How do we know that what we do is the best way to do it?

- Is there a better way to do this?

The answers to these questions often come from collected scientific evidence produced by research. The basis of evidence-based practice, as we will learn about shortly, is utilizing the best evidence available to help inform current clinical practice.

The integration of research findings into healthcare settings has been happening on some level for hundreds of years (Hall & Roussel, 2014). Practitioners and even lay persons took what they learned in their application of some medicinal properties, shared this information, and implemented it into a broader population. However, the research was limited and often not based on sound science and often not shared past a smaller community.

In recent years, starting in the late 20th century, evidence-based practice became a concentrated focus in nursing. Nursing now has developed various models, including the triad of EBP, to help guide EBP into practice.

Evidence-based practice in nursing is based on three principles, or the triad of EBP. At the core of the triad is improved patient/clinical outcomes.

These principles of the Triad of EBP include:

- Patient preferences or values

- This means, if the patient’s own situation renders the intervention not appropriate for them, or if their own social or cultural values do not align with the intervention, then the process stops there.

- Clinician expertise

- Decision making also includes the individual clinician’s expertise, which includes academic knowledge, experiences with patient care, and interdisciplinary sharing of new knowledge (Polit & Beck, 2021). Even very strong evidence is seldom appropriate for all patients, so clinician expertise is important.

- Best available current clinical evidence

- The basis of EBP is to de-emphasize utilizing tradition, opinions, and anecdotal evidence.

- Therefore, the best evidence is essential to EBP. We will explore how to determine which evidence is “best” in a bit. But, for now, just know that whatever evidence, whether we determine it to be “best” or not, is never enough by itself for the foundation of a clinical decision-making process.

- Finally, a big concept of this is knowing that one research study (even if it is the best study ever) does not equal EBP. This means, we must consider multiple pieces of evidence to consider synthesizing the results. We will come back to this.

Evidence

Evidence is a collection of facts believed to be accurate and true. These facts come in different forms. External evidence is generated through rigorous research. This type of research is intended to be generalized to other settings and clinical practices. External evidence refers to evidence from scientific literature—particularly the results, data, statistical analysis, and conclusions of a study. Internal evidence is typically generated through practice initiatives such as program evaluations, quality improvement projects, and outcomes management. Normally, these types of projects use internal data in an organization to make improvements.

Scientific Evidence

Scientific evidence is produced from scientific research (National Academies of Sciences, 2019). The researcher will use a systematic and objective method to obtain data. The scientific method is based on empirical data gathered through the senses (rather than personal beliefs, guesses, or assumptions) in an unbiased approach. Scientific evidence is used to support or refute scientific theories or hypotheses. Empirical evidence is the information obtained through observation and documentation of certain behavior and patterns or through an experiment.

The scientific method includes the following steps:

- Identify a problem or phenomenon that needs to be studied.

- Ask a question.

- Formulate a hypothesis or testable explanation.

- Designing an experiment to test the hypothesis.

- Analyze the data and make conclusions.

- Communicate the results.

Scientific evidence is characterized by:

- Objectivity

- Reliability

- Reproducibility

The scientific method might sound vaguely familiar to you as a nursing student. It has a very familiar problem-solving approach in the nursing process and the Clinical Judgment Model (NCLEX,n.d.) – Identifying a problem area, establishing a plan, collecting data, and evaluating it. However, the two approaches have very different purposes. While the problem-solving approach seeks a solution for a specific person or setting, the scientific method aims to obtain knowledge that can be generalized to other people and broader settings. For example, a nurse might be concerned about how to teach Mr. Jones, a postoperative hip replacement patient, to self-administer a prophylactic venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention injection. Scientific research, in contrast, would be concerned with the best approach to use with patients, in general, for self-administering prophylactic VTE prevention injections.

Table: Comparison of Nursing Process, CJMM, and Research Process

| Nursing Process | NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model | Research Process |

| (Approach) | Recognize Cues | Review Literature |

| Assess | Analyze Cues | Identify a Problem |

| Diagnosis/Analysis | Prioritize Hypotheses | Design a Study |

| Plan | Generate Solutions | Collect Data |

| Implement | Take Action | Analyze Data |

| Evaluate | Evaluate Outcomes | Interpret Results |

As we have learned already, EBP is the result of research. EBP itself is not research. Research, as we will learn more about, is a systematic investigation about a perplexing problem or something we desire to find more about. Research produces evidence, and then we take the best of that evidence and apply it to clinical settings – and that is EBP.

As we dive further into this course, we will be learning how to locate evidence that helps to guide our nursing actions. For the most part, nurses utilize library (or other) databases that house peer-reviewed, scholarly articles that are based on research projects. Luckily, as a student, you have access to the university library databases for no cost to you. We can also find clinical guidelines that are based on evidence in multiple locations, including UpToDate, which is a clinical medicine database that provides coverage of over 8500 topics, Joanna Biggs Institute EBP Database (JBI), the National Guideline Clearinghouse (AHRQ), Institute of Medicine (IOM), and others.

Purposes of Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing

As we have learned already, EBP is the result of a collection of research. EBP itself is not research. Research, as we will learn more about, is a systematic investigation about a perplexing problem or something we desire to find more about. The first step in EBP, as we will learn more about in an upcoming chapter, is to identify a clinical problem or question. Research produces evidence to help answer that clinical question, and then we take a collection of the best of that evidence and apply it (if applicable with patient values and clinician expertise) to clinical settings – and that is EBP.

Table: Research and EBP

| Research | Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) |

| Systematic & planned investigation | Systematic research for, and appraisal of, best evidence to help answer a clinical question |

| Specification of a problem to be investigated | Use of evidence for making clinical decisions, the evidence often being produced by research |

| Statement of predetermined outcomes | Account taken of individual needs of the client, as well as research-based evidence |

| Contributes to understanding of the world | Brings about changes in practice |

That brings us to ask, “What are the various purposes of research in the first place?” Researchers must ask a question that they would like to explore with a study (we will come back to that in detail later in an upcoming chapter). First, let’s explore five types of research purposes and the inquiries that are linked back to EBP:

- Exploration: To investigate a new area where little information exists.

- Description: To describe characteristics or functions of a particular phenomenon or population.

- Explanation: To explain why and how something happens, identifying causes and effects.

- Prediction: To predict future occurrences based on existing data and trends.

- Control: To find ways to influence or manage outcomes or variables.

- Evaluation: To assess the effectiveness of programs, interventions, or policies.

- Development: To contribute to the creation of new theories, practices, or technologies.

These purposes help in advancing knowledge, improving practices, and informing decision-making in various fields. Utilizing the nursing research purposes listed above, and remembering that the first step in EBP is to identify a problem and ask a question, here are the common types of research questions used in nursing research:

- Therapy/Intervention:

- The purpose of these clinical questions/inquiries is directed by health care/nurse researchers to learn more about specific treatments, interventions, actions, products, or processes.

- Example: Does a smoking cessation program increase the number of adult patients over the age of 18 who quit smoking?

- Diagnosis/Assessment:

- The purpose of these questions is concerned with methods and instruments utilized to help diagnose or screen a condition or to assess a clinical outcome.

- Example: Smith and colleagues developed and rigorously evaluated the Checklist for Postoperative Total Hip Replacement Discharge using data from 1,445 patients in two hospitals. The checklist was designed to assess whether discharge checklists were helping to optimize function and follow-up.

- Prognosis:

- The purpose is concerned with understanding the eventual outcomes or consequences of diseases, conditions, or health problems.

- Example: This study investigated the rate of obesity amongst individuals with limited access to fresh produce.

- Etiology (Causation [think “cause and effect”])/Prevention of Harm:

- The purpose is all about understanding the cause or determinant of what results in a health problem. Determining factors and exposures that lead to, cause, or affect various illnesses, mortality, or morbidity is the focus of this type of inquiry.

- Example: This study identified factors associated with the risk of fatalities among smokers infected with the coronavirus.

- Meaning and Processes:

- Think of the purpose here as gaining insight into our clients’ perspectives. This type of study is done via qualitative methods, which we will learn about soon. There is no intervention or measurement being done, but simply a study to investigate how clients perceive their treatments, diagnosis, etc., to better understand how we can motivate compliance with treatment and design appealing interventions.

- Example: This study explored the experiences and journey through diabetes of women in the U.S.

![]() Knowledge to application link: Research Purposes

Knowledge to application link: Research Purposes

Let’s do a little practice on the types of nursing research purposes. Drop in the box the type of research purpose you think is being utilized.

Understanding the Nurse’s Role in EBP

EBP is not just about individual nurses researching and deciding on patient care independently. In healthcare settings, hospitals and institutions establish clinical protocols, policies, and guidelines based on the best available evidence, ensuring that patient care is safe, consistent, and legally sound. Nurses are expected to follow these established protocols, as they are designed to align with national standards and best practices.

Hospitals and healthcare organizations have dedicated research committees, policy teams, and quality improvement departments that review new research and translate it into standardized protocols. These protocols are not optional—they are legally required and serve as a foundation for patient care, reducing variability and ensuring patient safety.

However, while nurses are legally required to adhere to hospital policies, they still play a critical role in evidence-based practice by:

- Recognizing outdated practices and bringing concerns to leadership.

- Engaging in quality improvement efforts that help refine current protocols.

- Critically appraising new evidence and contributing to discussions on clinical updates.

- Advocating for patient-centered care within the framework of established guidelines.

Rather than making independent care decisions based solely on personal research, nurses contribute to evidence-based care by questioning, evaluating, and participating in the process of protocol development and refinement. By understanding this balance, nurses can be both evidence-informed and protocol-compliant, ensuring that care is not only up-to-date but also legally and ethically sound.

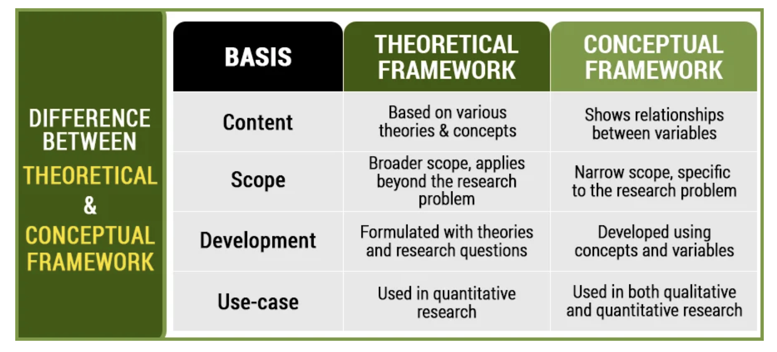

Conceptual & Theoretical Frameworks

One tricky concept that underlines the basis for research projects and much of the “why” and “how” in a phenomenon is the term “conceptual frameworks” (or “conceptual model”). You can think of this term as a fancy phrase for “a way to explain something”. Conceptual frameworks, as a broad phrase, are the use of theories, models, or concepts to guide research, nursing research, and nursing practice. The link between theory and research is reciprocal in their relationship. Every study contains a framework as a foundation to guide the research. Think of a framework as the frame of a house before the sheetrock, doors, and windows are inserted. Without the frame, the sheetrock, doors, and windows would have no support.

Remember, nursing is a mix of science and art, and we care for people in a variety of ways. For example, Florence Nightingale, considered one of the first nurse researchers and a holistic nurse, wrote about the impact of the environment to health (Nightingale, 1860). We still use Nightingale’s theories of this health-environmental framework: providing fresh air, light, cleanliness, and controlling odor. Another nurse theorist, Dr. Jean Watson, developed the conceptual framework of the “Watson Caring Science Theory” that includes a human caring approach to patient care (Watson, 2020).

As you start to read published research articles, be on the lookout for conceptual or theoretical frameworks. Many authors list their underlying framework that guided their project. Here’s another example close to home. I used a theoretical framework in a study I conducted about the correlation between how adult learners perform in their associate degree of nursing (ADN) biological science prerequisites and how they do in pharmacology and pathophysiology in nursing school. Can anyone guess what type of framework I might have utilized? If you guessed something like, “Knowles’ Theory of Adult learning”, you are correct! This theory is based upon an educational and learning theory. Knowles’ theory is based upon six assumptions, which are the basis of the theory of andragogy (Merriam & Bierema, 2014). Andragogy assumes educators need an understanding and respectfulness of the adult learners’ individuality. Since ADN students are all adult learners, this theoretical framework served to be a solid underpinning for the focus of my study.

![]() Knowledge to application link

Knowledge to application link

In this following article titled, A randomized controlled trial of enhancing positive aspects of caregiving in Thai dementia caregivers for dementia, they used the Kramer’s two-factor adaptation model as a framework for their study.

Here is a handy table that shows the difference, albeit sometimes there is a blurry line, between conceptual frameworks and theoretical frameworks.

| Conceptual Framework | Theoretical Framework |

|

|

Finally, researchers are creating new theories, test existing theories, and add to existing theories to explain the “why” behind things. Think of an infection control framework/model. What might be a study that could use this model? How about handwashing to prevent infections? Yes! That would be perfect. As we continue to learn about appraising research, we will come back to conceptual frameworks.

![]() Critical Appraisal! Frameworks:

Critical Appraisal! Frameworks:

- Did the report describe an explicit theoretical or conceptual framework for the study? If not, does the absence of a framework detract from the study’s conceptual integration?

- Did the report adequately describe the major features of the theory or model so that readers could understand the conceptual basis of the study?

- Is the theory or model appropriate for the research problem? Does the purported link between the problem and the framework seem contrived?

- Was the theory or model used for generating hypotheses, or is it used as an organizational or interpretive framework? Do the hypotheses (if any) naturally flow from the framework?

- Were concepts defined in a way that is consistent with the theory? If there was an intervention, were intervention components consistent with the theory?

- Did the framework guide the study methods? For example, was the appropriate research tradition used if the study was qualitative? If quantitative, do the operational definitions correspond to the conceptual definitions?

- Did the researcher tie the study findings back to the framework at the end of the report? Were the findings interpreted within the context of the framework?

Quality Improvement and Research Utilization

Lastly, to round out this first module, let’s chat about research utilization and quality improvement. These are two phrases that you will hear in the clinical setting as well as within research articles that you may read.

Research utilization (RU) is the act of using published evidence in a clinical setting. The difference between this concept and EBP is that research utilization may lead to changes in practice that are based on the results of one study, whereas EBP answers a clinical question based on an in-depth literature search conducted to find all relevant current research evidence related to that problem.

Quality improvement (QI) projects have a goal of improving patient outcomes, but they don’t involve extensive literature reviews and are usually specific to just one facility in order to improve an existing problem. The purpose of QI projects may be to improve workflow processes, improve inefficiencies, reduce variations in care, and address clinical or even educational problems.

EBP, RU, and QI frequently overlap. There are subtle differences.

Table: Differences Between EBP, Research, Research Utilization, & Quality Improvement

| Definition | Purpose | |

| Evidence-Based Practice | The intentional application of current best evidence, clinician expertise, and patient values to make decisions that will result in best patient outcomes | To improve patient outcomes and advance the discipline of nursing |

| Research | Experiments to examine a topic; uses processes to sample populations so the best representation of a population is present | To discover new knowledge and advance the discipline of nursing |

| Research Utilization | Applying research knowledge into clinical practice; used before evidence-based practice | To improve patient outcomes and advance the discipline of nursing |

| Quality Improvement Projects | Projects implemented and the results are studied; is site specific so the results may not be the same at another facility | To improve patient outcomes |

Evidence-based practice (EBP), research, and quality improvement are all important for providing safe healthcare, but they each serve different roles. According to the National Academy of Sciences (2020), nurses play a key role in improving healthcare systems, conducting research, applying research findings in practice, and advocating for policy changes.

Research and quality improvement gives us the evidence we need to make decisions in EBP. Most evidence comes from these two areas. That’s why it’s important for nurses to understand and use both research and quality improvement to provide high-quality care. EBP can also guide research and quality improvement. When EBP shows gaps in knowledge, research is needed to fill those gaps. When EBP shows consistent data, quality improvement can help ensure practices are followed correctly.

All three processes – EBP, research, and quality improvement – are essential for making sure healthcare practices are the best they can be.

The EBP and research process includes:

- Identifying a problem.

- Gathering and evaluating information.

- Implementing a solution based on evidence.

- Checking to see if the solution worked.

To start with EBP, you need to identify a practice problem. Then, use research and evidence to improve patient care. Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt (2019) suggest asking these questions:

- Is the information reliable?

- What results are available?

- Will the results help improve patient care?

It is very important to use practices that are supported with evidence to work in healthcare. This has led to more focus on research and EBP. Using our thinking skills, intuition, and information analysis helps us find, evaluate, and use evidence in clinical decisions, which affects patient outcomes. Often, there isn’t clear, strong evidence to support clinical decisions. Nurses have to make real-life decisions quickly, with limited information. Therefore, any action taken must be practical and sensible (Cannon & Boswell, 2010). This shows why it’s important for nurses to be good at EBP, quality improvement (QI), and using research.

Quality Improvement (QI) uses data and careful methods to make healthcare processes and outcomes better. QI focuses on improving patient outcomes. Unlike research, QI is usually specific to one site. The goal of QI is not to create general rules that apply everywhere but to improve specific processes at a particular site. However, if many sites find the same results through QI projects, these results can help form best practices. With more QI data available, QI is becoming a stronger way to improve healthcare.

In summary, overcoming barriers to using research in practice can enhance patient outcomes, reduce costs, and expand the knowledge base of the nursing profession. Nursing practice generates research questions, and research findings, in turn, inform nursing practice. Practice and research are interconnected and essential components of Evidence-Based Practice (EBP). Asking questions about nursing care often leads to scientific data, which in turn prompts further questions to explore.

Summary Points

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is essential in nursing for delivering high-quality, patient-centered care grounded in current, valid, and relevant research evidence.

EBP integrates three components: best available evidence, clinician expertise, and patient preferences/values to guide care decisions and improve outcomes.

The purpose of EBP is to enhance patient outcomes, ensure safety, maintain cost-effectiveness, and advance the nursing profession.

Nursing care must move beyond tradition and anecdotal practices to rely on scientifically supported methods for consistency and accuracy.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) and major nursing education reforms (Carnegie Foundation, Future of Nursing report) have emphasized EBP to improve quality, reduce costs, and expand nurses’ roles.

Outdated practices persist due to unit culture, tradition, reliance on authority, and the slow translation of research (up to 17 years) into practice.

Alternative sources of evidence—such as tradition, authority, anecdotal experience, and clinical expertise—should be critically evaluated before use in practice.

Disciplined research is the gold standard for producing reliable, generalizable evidence to inform nursing practice.

Types of research evidence include external (published studies, guidelines) and internal (quality improvement data, program evaluations).

The scientific method underpins research, characterized by objectivity, reliability, and reproducibility—mirroring the nursing process in systematic problem-solving.

Research produces evidence; EBP applies evidence to clinical practice in combination with expertise and patient needs. EBP is not research but depends on it.

Purposes of nursing research include exploration, description, explanation, prediction, control, evaluation, and development—each contributing to better practice decisions.

Common EBP research questions address therapy/intervention, diagnosis, prognosis, etiology/prevention, and patient meaning or experience.

Nurses’ role in EBP includes adhering to institutional protocols, identifying outdated practices, participating in quality improvement, and critically appraising new evidence.

Conceptual frameworks and theoretical frameworks guide research by providing a structured basis for understanding phenomena, designing studies, and interpreting results.

Quality Improvement (QI) focuses on site-specific process enhancements and patient outcome improvements, often without extensive literature review.

Research Utilization (RU) applies findings from individual studies to practice but is narrower than EBP, which synthesizes multiple sources of evidence.

EBP, research, QI, and RU are interrelated—research generates evidence, QI applies findings locally, and EBP integrates these for widespread practice improvement.

Barriers to EBP include resistance to change, lack of time, limited access to evidence, and entrenched habits; overcoming these is key to progress.

Strong EBP skills in nurses lead to better patient outcomes, cost savings, professional growth, and the advancement of nursing as an evidence-driven discipline.

Think About It

Think about these routine activities that nurses perform during a typical clinical day: making hourly rounds, turning patients every 2 hours, checking for pressure ulcers, monitoring oral temperature levels, and shift report. Reflect on what evidence your institution used as the basis for these practices.

Are these tasks in your practice setting supported by research, personal preferences, clinical guidelines, or traditions?

Case Study: A Gap in EBP

Riverside General Hospital (RGH) is a 250-bed hospital serving a diverse community. Despite a commitment to patient care, RGH staff have observed varied adherence to evidence-based practice (EBP) across different departments.

Identifying the Gap

A hospital-wide audit revealed that although RGH prides itself on providing excellent patient care, the implementation of EBP was inconsistent. The reasons identified for this gap included:

- Lack of access to evidence: Many clinicians reported difficulty in accessing the latest research papers due to paywalls or an outdated library system.

- Time constraints: Nurses and doctors were often too busy with their clinical duties to research and apply new evidence.

- Resistance to change: Some seasoned staff were hesitant to adopt new practices, favoring traditional methods they were more comfortable with.

- Lack of support: There was a perceived lack of support from the hospital administration for ongoing training and professional development in EBP.

- Clinical workload: High patient-to-nurse ratios left little time for staff to engage with and apply new evidence to their clinical practice.

- Lack of incentives: There were no clear incentives or recognition programs in place to reward staff for taking the initiative to implement EBP.

- Knowledge and skills gap: Some staff lacked the necessary training to appraise research critically and apply it to their practice.

- System barriers: The hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) system was outdated, making it cumbersome to integrate new EBP protocols into daily practice.

The Case of Chronic Heart Failure Patients

There have been multiple HF patients readmitted due to complications potentially preventable through EBP. The care team had not been implementing the latest guidelines for heart failure management, primarily due to the gaps identified.

Response and Strategy

RGH leadership decided to address these issues by implementing a multifaceted strategy:

- Improved Evidence Access: The hospital negotiated with publishers for better access to journals and updated the library resources, including online databases.

- Time Management: They introduced protected time for staff to engage in EBP activities.

- Change Management: EBP champions were appointed to facilitate the transition to new practices and mentor staff.

- Support Systems: Management began providing support for EBP training, including workshops and online modules.

- Workload Management: They adjusted staffing ratios and introduced support roles to decrease the clinical workload.

- Incentives Program: The hospital developed a rewards system to recognize and promote EBP initiatives among staff.

- Education and Training: RGH provided additional training for staff to improve their research literacy and critical appraisal skills.

- System Overhaul: The hospital invested in a state-of-the-art EHR system that supports the integration and tracking of EBP.

Outcomes

Six months after the implementation of these strategies, RGH reported:

- An increase in staff engagement with EBP resources.

- Improved patient outcomes, as evidenced by a reduction in readmission rates.

- A cultural shift towards acceptance and enthusiasm for EBP.

- Recognition of staff efforts through the new incentives program.

Conclusion

The readmission cases and the ensuing strategic changes at RGH illustrate that addressing the gap in EBP requires a comprehensive, multi-level approach. By recognizing and acting upon barriers such as lack of evidence access, time constraints, and resistance to change, RGH moved towards closing the EBP gap, ultimately improving the quality of care provided to its patients.

![]() EBP Poster Application! You will be choosing your EBP Project topic soon, if not already. The topic will be nursing related. Meaning, it will morph into something a Registered Nurse can do independently without a physician’s order. See the accompanying topic list in Appendix D and think about which one you might want to choose.

EBP Poster Application! You will be choosing your EBP Project topic soon, if not already. The topic will be nursing related. Meaning, it will morph into something a Registered Nurse can do independently without a physician’s order. See the accompanying topic list in Appendix D and think about which one you might want to choose.

Example: One of the topics is Treatment of Pediatric Pain. Some ideas to start considering with this topic are:

- What are some signs/symptoms of pain in pediatrics?

- What are some detrimental effects of pain in this population?

- What are some interventions that are commonly used (non-pharmacological) currently?

- What is an independent (not needing a physician’s order) intervention that an RN could do to help minimize pain in this population?

With the above questions, you are starting to establish the Introduction section of your EBP poster.

Attribution & References

“Green check mark” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

“Light bulb doodle” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

“Magnifying glass” by rawpixel licensed CC0

“Orange flame” by rawpixel licensed CC0.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. (2016). Feeding tube placement. https://www.aacn.org/newsroom/feeding-tube-placement

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2021). The Essentials: Domain 4: Scholarship for the Nursing Discipline. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Essentials/Domains/Scholarship-for-the-Nursing-Discipline

Benner, P., Sutphen, M., Leonard, V., & Day, L. (2010). Educating Nurses: A Call for Radical Transformation. Jossey-Bass and Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Cannon, S., & Boswell, C. (2010). Challenges and opportunities for teaching research. In L. Caputi (Ed.), Teaching nursing: The art and science (2nd ed.). College of DuPage Press.

Gale, R., Redner-Carmi, R. & Gale, J. (1977). Impact of the respiration of ornamental flowers on the composition of the atmosphere in hospital wards. International Archives of Occupational & Environmental Health, 40, 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00381413

Hall, H. & Roussel, L. (2014). Evidence-based practice: An integrative approach to research, administration, and practice. Jones & Bartlett.

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Malloch, K., & Porter-O’Grady, T. (2015). Innovation and evidence: A partnership in advancing best practice and high-quality care. In B. M. Melnyk & E. Fineout-Overholt (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (3rd ed., pp. 255–273). Wolters Kluwer.

Merrian, S. B., & Bierma, L. L. (2014). Adult learning: Bridging theory and practice. Jossey-Bass.

Munro, C. & Savel, R. (2016). Narrowing the 17-year research to practice gap. American Journal of Critical Care, 25(3), 194-196.

National Academy of Sciences. (2020). The future of nursing 2020-2030: A consensus study from the National Academy of Medicine. Author.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Scientific Methods and Knowledge. National Academies Press (US). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547541/

Nightingale, F. (1860). Notes on nursing: What it is and what it is not. D. Appleton & Company. http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/nightingale/nursing/nursing.html

Pankong, O., Pothiban, L., Sucamvang, K., Khampolsiri, T. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of enhancing positive aspects of caregiving in Thai dementia caregivers for dementia. Pacific Rim Internal Journal of Nursing Res, 22(2), 131-143.

Polit, D. & Beck, C. (2021). Lippincott CoursePoint Enhanced for Polit’s Essentials of Nursing Research (10th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health.

Park, S., & Mattson, R. H. (2009). Therapeutic influences of plants in hospital rooms on surgical recovery. HortScience , 44(1), 102-105. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.44.1.102

Relias Media. (2015). Misplaced NG tubes a major patient safety risk. Healthcare Risk Management. https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/135136-misplaced-ng-tubes-a-major-patient-safety-risk