Inclusion in Disability Evaluation and Surveillance Projects: Reflections and Recommendations for Inclusive Project Teams

Tamara Douglas; Nathan Rabang; Marlene Anna Attla; Tasha Boyer; and Vanessa Hiratsuka

Douglas, T. M., Rabang, N. J., Attla, M. A., Boyer, T., & Hiratsuka, V. (2024). Inclusion in disability evaluation and surveillance projects: Reflections and recommendations for inclusive project teams. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 4(2), 102-111. https://doi.org/10.59620/2694-1104.1087

Plain Language Summary

Disability advocates use the phrase “nothing about us, without us.” This means no research should be done on people with disabilities without people who have disabilities on the team. The authors of this paper had an individual who has a disability and found the training and survey were not easy to use. The team changed parts of the survey process to make it easier so the team members who experienced a disability could take part. After finishing the project, the authors recommend involving people with disabilities in the whole process, being flexible, talking a lot, providing better training, and hiring people who will stay.

Abstract

Disability rights advocates emphasize “Nothing about us without us,” yet a program evaluation or surveillance team’s composition rarely reflects inclusion of the individuals from the disability populations they focus on. Individuals who have lived experience with disabilities should be present during all steps of program evaluation and surveillance projects in meaningful ways to progress the impact of disabilities work. In this paper, we describe a process used by staff at Alaska’s University Centers for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCEDD) to hire, train, and work with individuals with intellectual, development disabilities (IDD) as team members. The case example for the inclusion effort was the National Core Indicators (NCI) In-Person Survey (IPS). Recruitment started in December 2020 with Zoom interviews for the NCI IPS occurring from March through August 2021. The project team included ten staff members, one of whom also was an individual who experiences an IDD (partner interviewer). Team members completed web based and Zoom training sessions. Throughout the training and onboarding process, project leads sought to modify the training and project implementation to better suit the expressed needs of all team members. To support the partner interviewer with IDD, two team members with research and program evaluation experience served as “lead” interviewers. Project leads also created a simplified version of the NCI IPS instrument for data collection. Multiple training sessions were held to acclimate the lead and partner interviewer with the team interview process and modified data collection instrument. Recommendations for improving our UCEDD program evaluation and surveillance inclusive practices were noted: Involve individuals with disabilities in every part of project planning processes; allow team members agency in selecting their projects and room for flexibility if research plans don’t work out; establish open communication and safe spaces for all team members; provide comprehensive, accessible, and equitable training; give team members a sense of timelines and trajectories of research projects with regular check-ins; adjust practices for an increasingly online work environment with COVID-19; develop accessible training, data collection and data entry systems; and invest in all team members long-term.

Introduction

Disability rights advocates have emphasized “Nothing about us without us,” yet evaluation and surveillance related to individuals with disabilities continue to be conducted by teams that rarely include individuals from the disability populations of the project’s focus. Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) demand meaningful attention in the conduct of research and evaluation with significant changes in the individuals conducting essential activities (Crimmins et al., 2019). In addition to the ethical frameworks and toolkits, there is a needed description of actions taken to augment or overhaul the structures and practices used in hiring, training, and managing program evaluation and surveillance projects. The needs and desires of those with intellectual, developmental, and physical disabilities should be present at all steps in the lifespan of projects about individuals with disabilities.

As described by Bigby et al. (2014), “Inclusive research has been framed as; participatory, collaborative, co-researching, cooperative, partnership and people led” (p. 4). The extension of the tenets of inclusive research, such as an orientation to research (that we believe should be extended to program evaluation and surveillance) that focuses on relationships, grounded in the principles of co-learning, participation, mutual benefit, and long-term commitment, are essential foundations for inclusion (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). The participatory action research (PAR) goal of meaningful social change brought about by a group of people that includes the population of interest as influential members of the team is a necessary orientation and practice. PAR originates with the community of interest. This shift in power from being researched, evaluated, and surveyed to being in the position to identify the problems, research questions of interest, and monitoring of community well-being is a key component of PAR (den Houting et al., 2021). Additionally, those who are collecting and analyzing data, and determining which actions should occur based on the information, should include individuals with disabilities (Coons & Watson, 2013). Knowledge production in disabilities is incomplete and ineffective if the team conducting and implementing such efforts is missing those with lived experiences of having intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD).

Equitable and inclusive practices in research have begun to be described by disabilities-inclusive research groups such as the Academic Autism Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education (AASPIRE) group, which has created and disseminated equitable approaches to research (Nicolaidis, 2019). The practice of modifying research protocols to include people with IDD as researchers remains infrequently described in the literature except for pioneering research groups (Stack & MacDonald, 2014). Less well described is guidance on the inclusion of individuals with disabilities in evaluation and surveillance.

Program evaluation and public health surveillance are far more common than research projects, as they are often required activities for externally funded programs. Program evaluation is often a required activity in federal- and state-funded programs. Health surveillance is used to monitor the health status and health outcomes of populations over time using standard surveys and data collection procedures. The inaccessible culture of research is a noted barrier in inclusive research. Program evaluation and surveillance may offer entry as individuals with IDD are customers of the very programs under scrutiny and have the lived experience that is the topic of surveillance inquiry.

Like Nicolaidis et al. (2019), we offer our experiences in adapting and expanding a surveillance and evaluation project to share our practices and pitfalls, not to be prescriptive. We believe that inclusive research, evaluation, and surveillance improves the quality, utility, and validity of the work and are ethically imperative. The literature on inclusion in disability research focuses on models, toolkits, and ethical frameworks for conducting inclusive research. However, the lived experience of using these ideas is rarely presented. Furthermore, inclusion of individuals with IDD in program evaluation and surveillance teams has not been described to date. The purpose of this manuscript is to retrospectively describe the rationale, process, and outcomes of an academic evaluation and surveillance team modifying an existing project to support inclusion of researchers with IDD. This case study is intended to help our team and others conducting research and evaluation reflect on the application of theory into disabilities research practice. We humbly offer our experiences in hopes of advancing our DEI practices locally and supporting others who are attempting to practice inclusion in research, evaluation, and surveillance efforts.

Case Study

Alaska has been involved in the National Core Indicators (NCI) since 2016. National Core Indicators® – Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (NCI®-IDD) is a national effort to measure and improve the performance of public developmental disabilities agencies operated through the Human Services Research Institute (HSRI). NCI states collect data from and about individuals with IDD to improve long-term care policy and practice at the state and national levels, and to contribute to knowledge in the IDD field (NCI, 2023). In FY 2021, the State of Alaska, Department of Senior and Disabilities Services (SDS) partnered with the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Center for Human Development to conduct the NCI In-Person Survey (NCI IPS). A total of 950 participants were sampled by SDS to participate in the survey process. The participants consisted of adults with physical and developmental disabilities and IDD who receive Medicaid Home and Community Based waiver services within the state of Alaska.

Between December 2020 and February 2021, 10 interviewers were hired to conduct the survey. Interviewers were deliberately chosen from various parts of the vast state and their familiarity with IDD. Two interviewers were family members of individuals with IDD, and one was a special education teacher. One of the 10 interviewers, who is an author of this manuscript, was a “partner interviewer” with lived experiences with IDD. The partner interviewer conducted the informed consent and Section I of the NCI IPS, asking the participant the items that pertain to personal experiences and require subjective responses. The interviews with participants were conducted solely via Zoom because the interviews occurred between March and August of 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. A total of 254 interviews were conducted, two of which were partnered interviews.

Onboarding

As a national survey, the NCI IPS has specific minimum training requirements. It is a standard instrument with state-added questions that are not subject to change per state and follows a national protocol for implementation. The required standards for replicability leave NCI states with little room for staff accommodation or local staff input (with or without disabilities).

Human Services Research Institute (HSRI) required seven online training modules for all team members that took at 2 hours to complete. The modules included visual and audible pages of information, with a quiz at the end of each module. Navigation of the module layout was not user friendly for all interviewers because the buttons to click to move to the next page were hard to locate. The project lead assisted the partner interviewer with one-on-one support, describing much of the online module text in plain language, supporting in-webpage navigation and wayfinding to the next module in the series.

Once all online training was completed, the team met with HSRI staff for a required 2-hour Zoom training session on NCI and the IPS. During this Zoom call, additional site-specific training and onboarding occurred. This included location of materials, walking through the survey instrument, practice interviews, and using the HSRI database to enter completed survey data. The project lead worked individually with the partner interviewer to provide tailored training, more time to ask questions, and extra time to acclimate to the process. Various researchers practiced with the partner interviewer to allow for familiarity with all possible interview staff who they might work with in conducting the NCI IPS.

Instrument

The NCI IPS instrument consisted of over 100 questions over a span of 73 pages. Most questions were multiple choice, with clarifying verbiage available to assist should there be confusion from the participant. Many questions contained skip patterns to follow if the participant answered in a certain manner. The team members were trained thoroughly on the survey instrument and practiced with the leads prior to conducting live interviews. The project leads created a simplified version of the NCI IPS for the partnered interviewer and hosted multiple training sessions to acclimate team members to the revised instrument. The pair of team members met 10 minutes before each interview to review the instrument and flow of the data collection encounter.

Recommendations for Practice

Reflecting on the case study, we would like to share recommendations that ultimately point to more meaningful inclusion in program evaluation and surveillance.

Recommendations for Individuals

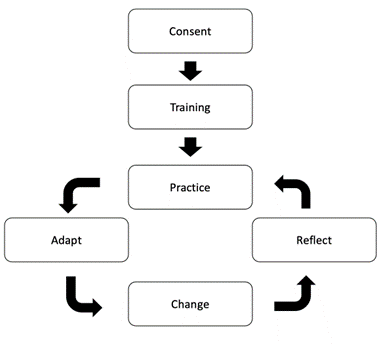

We recognize that, as a writing team primarily composed of individuals without IDD lived experience, it is not our place to tell individuals with disabilities what to do. We also recognize that the burden of advocacy ought not to fall solely on individuals with IDD. We recommend that evaluation and surveillance teams approach DEI with a degree of humility and curiosity—this work is relatively new in the field, and there is discomfort that may be felt between all team members involved. This is why it is important to wholly involve individuals with lived experience in the full process that we describe below and depict visually in Figure 1.

Agency in Research Project Delegation

Program evaluation and surveillance teams intending to include individuals with IDD lived experience should involve team members with IDD in every part of planning processes, should they consent to this degree of participation. This includes, but is not limited to, creating the project work plan, searching for and applying for grant or contract funding, developing shared timelines, designing training processes, creating tools for comradery-building between team members, conducting analyses, developing dissemination products (e.g., reports, presentations, manuscripts), and working with stakeholders to use the findings.

A common practice in academia is to assign individuals membership on project teams without much discussion beforehand. We recommend that steps are taken to ensure that individuals with IDD lived experience have full agency in determining their employment endeavors. Before assigning individuals with lived experience to projects, project lead should make sure to brief all team members on the scope of work and the option to decline proposed projects or request additional training and supports for projects that do not fit with their needs or previous training. When explaining the scope of work, it is important to have contingency plans if things go awry. There should be a plan on who to contact if problems arise in the evaluation and surveillance process.

Training

While much training for surveillance projects is often beyond the control of the project leads, we recommend that project leads create training alternatives that are comprehensive, accessible, and equitable. The goal of training is not to complete a quiz for a certificate, but to ensure all trainees understand and embody lessons learned and know what to expect from the upcoming project. This could look like setting aside one-on-one time with individuals with lived experience to review training materials, rewriting training overviews in plain language, and ensuring there is space for all participants to ask questions. Ultimately, we recommend that all project training be created with accessibility as a priority.

In the case study, the partner interviewer was provided over 10 hours of support over Zoom that were beyond the standard training. This support included accessible training and practice with the newly developed survey. Real-time support needs to be available as well. Our office leadership, project leads, and the computer support staff were available to assist the partner interviewer not only in the evaluation and surveillance process but in other meaningful ways around the virtual workspace.

Consistent Funding for Team Members

The employment security of many program evaluation and surveillance staff is contingent on grant/contract funding, meaning that an inconsistency in funding may require them to move to different projects or teams. While this cycle is somewhat inevitable, this transience of project members can counteract team building and comradery when team members do not know the long-term trajectories of their specific projects or employment.

We recommend institutions focus on long-term recruitment and investment of program evaluators, particularly individuals with disabilities. This can give team members a sense of the timelines of their projects and help minimize turnover. Importantly, team members are afforded the opportunity to master program evaluation and surveillance approaches (i.e., interview probing) rather than having sufficient but minimal experience with a practice.

Accessible Technology and Instruments

Accessible technology and research instruments are important to have during the data accumulation process in program evaluation and surveillance projects. Depending on the type of human subjects’ review, a research, program evaluation or surveillance project may be considered research by an institution or community. People conducting research must pass the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) human subjects research training before they are allowed to work on a research project. The CITI Program is a national program that all researchers who work with human subjects must complete. The CITI Program is a multi-module online set of courses, with materials that are not in plain language and can be inaccessible for individuals with lived experience with IDD. Although not available at the time of this project, Research Ethics for All has created the Social-Behavioral Research Ethics Education Program for Community Research Partners with Developmental Disabilities (Schwartz et al., 2024). Additionally, HSRI required a multi-module online set of courses for interviewers that also was not in plain language and could be inaccessible for individuals with lived experience with IDD. It took approximately 2 days for team members to complete various inaccessible modules. For example, one module had team members stuck because the “next” button was not labeled or easy to find, leaving team members unable to continue to the next module. If using an online training module, we recommend plain language with an interface that is user friendly with visual and screen reader options. We also recommend a training support line for individuals who might need more help.

When considering the instrument used in the project, the paper survey had to be reformatted for use by the partnered interviewer. Modifications included easy-to-use color skip patterns and removing jargon and instructions. Multiple training sessions were then conducted with the partnered interviewer to get comfortable with the revised instrument, and additional mock interviews were conducted. During mock interviews, the lead interviewer would verbally prompt the partnered interviewer to move to the next question in the skip pattern. We recommend using accessible survey formats with color patterns and easy-to-understand universal figures to follow skip patterns. For example, putting large red stop signs at breaks.

Last, the NCI IPS online data entry platform – Online Data Entry Survey Application (ODESA) – proved to be difficult to navigate. The data entry process required many computer mouse clicks to enter data per completed survey. None of the pages were screen reader viable. We recommend online data entry that is accessible and streamlined. We recognize that the overhaul of a database is expensive and time-consuming.

Comradery Building

Strong team building and a sense of belonging make every office or work environment happier and more efficient. During the case study project, team members who volunteered to work with partnered interviewers participated in a meet-and-greet type of get-to-know one another meeting to see if they would want to work together. The overall project lead facilitated all-hands project meetings; the meetings were safe spaces to talk about difficulties with the project, sharing of best practices, and to keep the entire team updated on overall progress toward project goals. We recommend facilitation of a shared space/time for team communication because clear, open dialogue with everyone involved in the project is important for building a better and trusting team.

Discussion

Research, evaluation, and surveillance take place in ableist institutions with individuals who often have education and training from ableist educational institutions and lack lived experience as individuals with disabilities, particularly the lived experience of individuals with IDD. Program evaluation and surveillance usually occur within the academy, inside or outside governmental institutions, or in the administrative sectors. Program evaluation and surveillance sponsors tend to have stipulations on key personnel in level of education (e.g., university degree) and employment status (e.g., management), creating minimal qualification barriers for leadership and paid staff positions. Intellectual ableism is an underlying aspect of research, evaluation, and surveillance. For DEI work to progress, the prejudicial assemblage of concepts, actions, practices, and structures that default to the more able, result in the devaluing, silencing, and invisibilizing of members of the disabled community, particularly those with IDD (Campbell, 2021).

To counter ableism in research, evaluation, and surveillance, it is imperative to critically examine the concepts, actions, practices, and structures and redesign these activities to be explicit in their inclusive design (Campbell, 2021). Including individuals with disabilities in every aspect of program evaluation and surveillance is the only way to achieve true inclusion. Every attempt at inclusion will not be perfect but it must be done. Inclusion is an ongoing process that includes failure and growth. The ultimate failure is not trying.

Equally important is to be on the lookout for performative inclusion and take pains to avoid an increase in tokenism and exploitation of individuals with disabilities because DEI has become a buzzword (den Houting et al., 2021). The humanization of individuals with disabilities must occur with sincere respect for the expertise gained from lived experiences with disabilities (Botha, 2021). In the 21st century, the term “diversity hire” is readily used in the business and academic lexicon. Valuing diverse perspectives and listening to what individuals have to say is one step of the diversity hire equation. Following their advice and actively steering an institution to an inclusive environment is another aspect altogether. Hiring diverse groups of individuals is immensely valuable, but real change only occurs when leadership listens to diverse voices and changes the systemic inequality placed there after years of discrimination.

Our case example was a failure of good inclusion of individuals with IDD. However, we believe every project, from small program evaluation projects to national surveillance projects, can be inclusive with person-focused training, practices, accessible tools, and humility. We attempted to use the saying “Nothing about us without us” to make a national project aimed at helping individuals with IDD more accessible. We wanted colleagues with IDD lived experience instead of those with IDD being relegated to being the subject. Unfortunately, we found the project to be inaccessible at every turn. We are glad we attempted to make the project inclusive and now have more ideas on what to do and not to do in the future.

In summary, our recommendations for inclusion in evaluation and surveillance practice are as follows.

- Approach DEI with a degree of humility and curiosity.

- The project leader for the evaluation should brief potential team members on the scope of work, allowing people the option to decline working on proposed projects or request additional training and supports for project tasks that do not fit the needs or previous training.

- There should be a plan on who to contact if problems arise in the evaluation and surveillance process.

- There should be project-specific training that ensures all team members know what to expect from the upcoming project and how to accomplish their necessary tasks.

- Institutions employing program evaluators and surveillance staff should focus on long-term recruitment and investment of staff, particularly individuals with disabilities, to allow team members time needed to master their craft.

- Use of accessible survey and other data collection instruments and data input formats.

- Project leads should have regular facilitated meetings to build and maintain team communication and comradery.

References

Botha, M. (2021). Academic, activist, or advocate? Angry, entangled, and emerging: A critical reflection on autism knowledge production. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.727542

Campbell, N. (2021). The intellectual ableism of leisure research: Original considerations towards understanding well-being with and for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 25(1), 82-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629519863990

Coons, K. D., & Watson, S. L. (2013). Conducting research with individuals who have intellectual disabilities: Ethical and practical implications for qualitative research. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 19, 14-24.

Crimmins, D., Wheeler, B., Wood, L., Graybill, E., & Goode, T. (2019). Equity, diversity & inclusion action plan for the UCEDD national network. Association of University Centers on Disabilities.

den Houting, J., Higgins, J., Isaacs, K., Mahony, J., & Pellicano, E. (2021). ‘I’m not just a guinea pig’: Academic and community perceptions of participatory autism research. Autism, 25(1), 148-163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320951696

National Core Indicators (NCI). (2023). Who we are. https://idd.nationalcoreindicators.org/who-we-are/

Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D., Kapp, S. K., Baggs, A., Ashkenazy, E., McDonald, K., Weiner, M., Maslak, J., Hunter, M., & Joyce, A. (2019). The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism, 23(8), 2007-2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613198 30523

Stack, E., & McDonald, K. E. (2014). Nothing about us without us: Does action research in developmental disabilities research measure up? Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11(2), 83-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12074

Schwartz, A. E., McDonald, K., Ahlers, K., Anderson, E., Ausderau, K., Corey, J., Durkin, B., Fialka-Feldman, M., Gassner, D., Heath, K., Jones, J., Maddox, B., Myers, J., Nelis, T., Paiewonsky, M., Pellien, C., Raymaker, D., Richmond, P., Silverman, B.C., Terrell, P., Tillman, I., & Vetoulis-Acevedo, M. (2024). Research ethics for all: Development of a social-behavioral research ethics education program for community research partners with developmental disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 101675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2024.101675

Wallerstein, N., & Duran, B. (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 100 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S40–S46. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036