Impact of County-Level Urbanicity on Quality of Life for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities in a Rural State

Alyssa M. Smith and Allison Caudill

Smith, A. M., & Caudill, A. (2024). Impact of county-level urbanicity on quality of life for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in a rural state. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 4(2), 182-201. https://doi.org/10.59620/2694-1104.1103

Plain Language Summary

People who have intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and live in rural areas often have a hard time finding the help they need to be healthy and make their lives better. This includes things to improve their quality of life such as going to the doctor or having safe housing. Researchers looked at information from surveys that people with IDD and their care partners filled out to see what people needed in their communities. This survey took place in a rural state where there was only one bigger city. They found that whether these people lived in small towns or a big city, they faced the same problems. This showed that no matter where they live, the people surveyed with IDD and their care partners might need the same kind of help to have a better life. More research is needed to understand this issue more and focus on giving people with disabilities what they need to make their lives better, whether they live in rural communities or in the city.

Abstract

People with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) face challenges, such as decreased access to physical, environmental, and social health-related services that can negatively impact their overall quality of life (QoL). Additionally, people living in rural communities may experience geographic distancing and other factors, like decreased transportation and available housing, that contribute to increased isolation and decreased health outcomes, overall. It is important to consider the QoL of people with IDD living in these communities given the additional intersectional constraints of rurality and having an intellectual disability or other co-occurring conditions. A secondary data analysis reviewed closed and open-ended survey data of respondents with IDD and care partners of people with IDD (n = 140). Results indicated that urban and rural-dwelling people with IDD and care partners had similar experiences. Some themes from the data included experiences of social isolation, the need for improved transportation and housing, and accessible healthcare and community resources. This data suggests comparable reported resource needs for people with IDD in both rural and urban sectors of rural states and demonstrates the need for continued study into resource disparities for this population. Future investigation should prioritize resource development related to the QoL of individuals with IDD and their care partners in both rural and urban geographic settings.

Introduction

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

Intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are a diverse range of diagnoses most diagnosed before the age of 18 that impact the lived experiences of individuals, regardless of race, ethnicity, education level, or socioeconomic status (National Institute of Health (NIH), 2021). Approximately 7.39 million people in the U.S. have IDDs and current research in the field indicates poorer outcomes and access to care compared to people without disabilities. Examples include decreased health with higher preventable mortality, decreased access to preventative healthcare, increased financial barriers to services, attitudinal and social barriers within society, and lack of formal training and staffing competency in those working with IDD in the medical and community context (Ervin et al., 2014; Larson et al., 2023; Office of the Surgeon General & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002). Additionally, decreased access to health-related services and social-environmental supports that support health promotion can also be a contributing factor (Laurence & Wendy, 2014). Disability can affect functioning in all aspects of daily life further highlighting the importance of evaluating the quality of life (QoL) of persons with IDD and their care partners to ensure resource and policy development continues to address this population’s most urgent needs.

Rural Considerations for People with IDD

The areas in which people live, work, age, and play can drastically affect their health outcomes and overall QoL. Rurality, or the characteristic of living in rural communities has been directly linked to health disparities: a community is defined as rural if the entirety of its population, housing, and general territory are not included within an urban cluster or urbanized area (Probst et al., 2019). Approximately one in five Americans live in a rural community and this is growing; the percentage of the national population classified as rural increased to 20.0% from 19.3% as reported in 2020 and 2010, respectively. For Vermont, nearly two-thirds of residents live in rural towns, and there is only one urban county in the state (Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), 2021; Probst et al., 2019). Historically, people from rural communities are more likely to be diagnosed with preventable conditions, such as obesity and diabetes, and more likely to engage in non-health-promoting behaviors such as smoking and substance abuse, than their urban peers (Richman et al., 2019; Stein et al., 2017). Rural populations, Vermont included, are more likely to experience poorer health outcomes, higher mortality, and public health disadvantages due to increased remoteness of housing and community resources (Probst et al., 2019). Geographic distancing contributes to increased isolation and the widening gap between urban and rural health outcomes overall, especially for populations with reduced transportation access, including people with disabilities (Fortney & Tassé, 2021).

For individuals who can access medical services, many report that their physicians and healthcare providers are inadequately trained in supporting people with disabilities, which can lead to stereotyping and unfair or inappropriate treatment (Caudill et al., 2022; Dassah et al., 2018; Hussain & Tait, 2015). This can have a rippling, detrimental effect on the health and well-being of people with IDD, especially as many have co-occurring mental health or psychiatric conditions; thus, making access to health and mental health services even more crucial (Yen et al., 2009). When considering the needs of people with IDD living in rural communities, specifically, healthcare providers must address service access and provision given the additional intersectional constraints of rurality and living with IDD or other co-occurring conditions. In all, individuals with IDD living in rural areas are at increased risk for poorer health, isolation, and reduced QoL compared to their same aged peers (Fortney & Tassé, 2021). Yet, there is a dearth of literature studying these effects and resource needs rigorously.

Quality of Life

The IDD literature has studied QoL paradigms extensively. Considered to be multidimensional in nature, QoL refers to satisfaction with overall life experiences and can guide individual, community, and system-level quality improvement efforts for people with IDD (Schalock et al., 2007, 2008). This manuscript aims to focus on one of the most well-established QoL frameworks, Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002), that has been validated cross-culturally and has widespread applicability to program development, system delivery, and outcome evaluation for people with IDD (Bonham et al., 2004; Jenaro et al., 2005; Verdugo et al., 2001). Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) conceptual framework of QoL includes eight core domains: personal development, self-determination, interpersonal relations, social inclusion, rights, emotional well-being, physical well-being, and material well-being (Schalock et al., 2008; Schalock & Verdugo, 2002). Previous studies support these domains representing a holistic conceptualization of QoL as an integrative framework that can be applied to an individual with IDD and their support systems (Beadle-Brown et al., 2009; Schalock, 2000; Townsend-White et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2010). Considering that people with IDD constitute a vulnerable population, QoL is exceedingly important to assess in this population. Several studies report that QoL is significantly higher for people without intellectual or developmental disability and that QoL is highly impacted by environmental factors (Simões & Santos, 2016; Williams et al., 2021). Similarly, previous research indicates a correlation between geographic location and QoL, with QoL being significantly higher for individuals in urban areas (Baernholdt et al., 2012; Kelly et al, 2022; Moss et al., 2021). Yet, there is minimal research tying this well-established model in a rural sample of individuals with IDD and their support systems. Thus, an assessment of this model’s ecological validity is warranted in the rural IDD population, especially in the setting of a rural state like Vermont that houses both urban and rural sectors within an overall minimally populated region.

The purpose of this study was to examine the perceived needs of residents with IDD to inform research on QoL, service delivery, and policy by examining the resource needs of people with IDD and their care partners in Vermont, a primarily rural northeastern state in the U.S., through a secondary data analysis of a statewide needs assessment. Our primary aim was to examine whether rural dwellers with IDD and their care partners face greater resource disparities than those living in urban settings. Our secondary aim was to explore whether a QoL framework from the IDD literature holds ecological validity, an important assessment of a models’ applicability to smaller participant populations, within a primarily rural sample population of people with IDD and their care partners.

Methods

Design

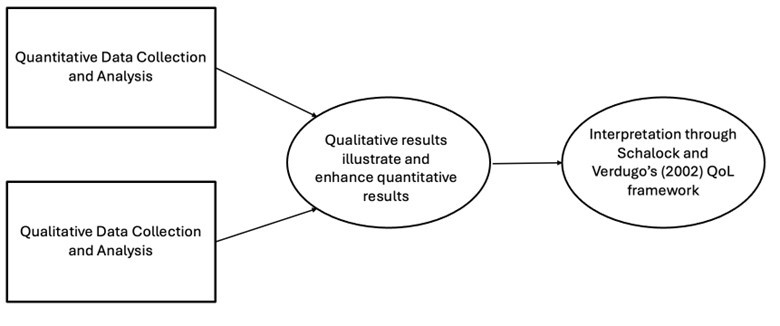

This study employed a convergent parallel mixed methods design to comprehensively investigate the barriers and needs within the IDD and care partner community in Vermont through a secondary data analysis of a community needs assessment designed to learn about the experiences and needs of people with disabilities in Vermont. Quantitative data were collected through closed-ended survey questions and analyzed using Chi-Square analysis and a binary logistic regression model. The purpose of this approach was to compare responses between rural and urban participants and examine relationships between variables. Simultaneously, qualitative data from two open-ended survey questions were analyzed using thematic coding to identify common themes. Themes were interpreted through the lens of Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) QoL framework. Qualitative themes were then integrated with the quantitative findings, achieving complementarity, and offering a more robust and nuanced understanding of the research question. This design allowed us to validate our results, explore the topic from multiple perspectives, and gain deeper insights into the experiences of both rural and urban residents with IDD and their care partners in Vermont. Figure 1 illustrates the mixed methods study design.

Measures

This study involved secondary analyses of a statewide survey assessing the lived experiences and needs of people with disabilities, close family members, and service providers in Vermont. The survey was developed as part of a larger data collection initiative to better serve the center and the community in understanding the gaps in resources for people with disabilities and their families. The survey included two main components: (1) demographics and (2) information related to an individual with a disability’s overall level of assistance, including community resources utilization and areas for continued support either through direct care support or via community resources. Demographic and survey data were collected from a group of respondents, including people with disabilities, family members or care proxies, or service providers. This was conducted electronically by the University of Vermont. The survey also included the Washington Group Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS) to describe participant functioning across six areas: vision, hearing, mobility, cognition, self-care, and communication (Madans et al., 2011; Washington Group on Disability Statistics [WGDS], n.d.). Specific questions aimed at identifying demographic characteristics, impairments related to disability, feelings of belonging, and top needs and barriers to resources within Vermont were selected for inclusion in this secondary data analysis based on their relation to the two aims of this study (differences in rural vs. urban experiences and QoL). Beyond WG-SS and demographic questions, open-response questions analyzed included were:

- What are the top needs for people with disabilities in Vermont?

- What are the biggest barriers for people with disabilities in Vermont?

- What services or supports are working well for you?

- What services or supports are not working well, difficult to get, or missing?

- Are there communities, groups, or places in Vermont where you feel welcome?

- Are there communities, groups, or places in Vermont where you feel excluded?

All participant data were de-identified before being shared with the analysis team. The institutional review board determined this study was exempt from full review.

Participants

Survey participants for the original study were recruited via snowball sampling over approximately four months (December 2022 – March 2023). Survey invitations were shared broadly on social media and websites and sent directly to state disability rights groups, service organizations, and advocacy organizations to recruit people with disabilities, close family members, and providers. Responses and subsequent data analysis were first conducted to develop a report to federal funders for review and dissemination. The original survey included 367 responses. Of this population, a filter was applied to the original data set in the statistics software to include participants who identified as a “person with a disability,” a “parent or caregiver of a person with a disability,” or “another close family member to someone with a disability” to fit the criteria of the immediate lived experience of someone with a disability or the definition of a care partner which include parents, close family member, and romantic partners (Bennett et al., 2017). We then applied a secondary filter to sort the population into those who identified their disability, or their close family member/individual’s disability as: “autistic, person with autism, or neurodivergent,” “developmental disability,” or “intellectual disability.” Because the survey was developed by another party, the authors were unable to discern within the identified data if care partners were identifying only the diagnosis of the person with whom they worked, or if they shared the same diagnosis identified in their response. Therefore, it was assumed the diagnosis recorded by a care partner was for the person in their care only. Based on the application of these filters, a total of 140 responses were included for analysis.

Methodology and Guiding Paradigms

A literature review was conducted to guide the principal research question for this secondary analysis. A synthesis matrix of the literature was developed for a thorough review of current articles related to QoL factors and IDD to identify needs and the current evidence base for community intervention. The two authors agreed upon using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) method for qualitative analysis of free-response survey questions. Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework for thematic analysis was used. The six steps are outlined in Table 1.

| Braun & Clarke (2006) six-phase framework for thematic analysis | Specific actions taken by the research team for each step |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Become familiar with the data | All open-ended question responses were anonymized and inputted into a spreadsheet. Each author read through the entire dataset independently. |

| Step 2: Generate initial codes | Initial codes were developed and marked during the second readthrough. Both authors came together to evaluate and cross-compare individual codes. Any discrepancies were addressed and resolved, and the authors reached a consensus. A codebook was developed, and the two authors re-coded all responses using the developed codebook. |

| Step 3: Search for themes | Codes and participant quotes were examined to categorize patterns capturing significant findings among the data. Themes and sub-themes developed were particularly descriptive and responses from both urban and rural respondents were included to support all themes developed.

Initial themes developed were then further categorized into three larger, over-arching themes. There were three larger qualitative themes identified, each with 3-4 contextualizing sub-themes. |

| Step 4: Review themes | The authors first assessed the data-derived themes to confirm they were relevant to the research question as well as separate and distinctive from each other.

Themes and sub-themes were then reviewed using Schalock and Verudgo’s (2002) Quality of Life (QoL) model. Domain descriptions and indicators from the QoL model were used to group data-driven themes with model domains. |

| Step 5: Define themes | Definitions were developed for each theme to further highlight their connection to the original eight QoL domains. |

| Step 6: Write-up | Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) QoL model was adapted to highlight the juxtaposition of the themes from this dataset to the original model.

Participant quotes from both urban and rural survey respondents were identified to further support the thematic analysis process. |

This model was used to guide both the evaluation of both quantitative and qualitative data, which has been critically assessed cross-culturally (Schalock et al., 2005). The conceptual model is comprised of domains, indicators, and factors. Factors, such as independence, well-being, and social participation, are the highest-order constructs that overview the subsequent domains and indicators. There are eight QoL domains, and each includes a set of numerous factors, describing the multidimensional components of each domain. Finally, the model includes several QoL indicators that are referenced as domain-specific perceptions, conditions, and behaviors that indicate a person’s well-being (Schalock et al., 2008; Schalock & Verdugo, 2002; Verdugo et al., 2001). Each domain’s listed exemplary indicators were considered when comparing data to the overall framework to further analyze our findings. This methodology was chosen to compare the current data with the literature related to QoL and consider this model’s current ecological validity to the surveyed participants to assess its applicability to a more rural sample population.

Ecological validity determines how results of a study can be generalized to a real-life setting or population, or, how well a specific study design represents the targeted phenomenon of interest (Fahmie et al., 2023; Lewkowicz, 2001). This differs from external validity in which random sampling of a population can be generalized to other contexts. This can be difficult for samples with more sociodemographic restrictions and additional intersectional contexts like medical co-morbidities and diagnoses (Andrade, 2018). Further, previous critiques of ecological validity have found that when research objectives center on promoting societal change, an emphasis on ecological validity becomes increasingly important to demonstrate sustainability of findings (Fahmie et al., 2023; Kyonka & Subramaniam, 2018). One identified method for increasing ecological validity in research is using participant-informed sources, such as open-ended surveys directly sampling the population of interest (Fahmia et al., 2023). Additionally, ecological validity is considered a judgment rather than an established statistic or analytic outcome (Andrade, 2018). Thus, assessing ecological validity is increasingly important in small, less generalizable samples like the rural IDD population of Vermont is important to further assess the applicability of such findings to lesser-known regions and participants.

Data Analysis

To evaluate the first aim, quantitative and qualitative data obtained from the closed and open-ended questions were used for analysis. The open-ended questions were qualitatively analyzed using the Braun and Clarke (2006) approach of thematic analysis. Participant groups were created based on reported town/city of residence according to U.S. census data. All statistical analysis for quantitative data was conducted in SPSS 29. Chi-square analysis was conducted for yes/no questions between groups; those who did not identify a geographic location were not included in the quantitative analysis for the determination of between-group differences (n = 32). For Likert-scale responses, a binary linear regression model was applied to increase the power of analysis between groups.

To evaluate the second aim, the qualitative themes that emerged from the open-ended responses were cross-compared to the domain descriptions. The authors independently cross-compared themes to descriptions of the domains and their described indicators and then came together to assess the thematic ties between the raw data from the open responses and the given model. The authors unanimously agreed to the matches between the described domains and their indicators with the themes conceptualized from the data. The two authors addressed all discrepancies through regular discussions to reach a consensus on themes and to, therefore, enhance the dependability of the findings and overall study rigor.

Results

Quantitative Results

Three participant groups were identified during survey analysis: urban (n = 61), rural (n = 47), and non-specified geographic regions (n = 32). Participant demographics indicated that the participants in the study were primarily between 35-65 years of age (65.7%), female (69.0%), and non-Hispanic White (83.4%). According to U.S. census data, this is closely aligned with the representation for the northeastern part of the country which is 51% female and with a median age of 40.5 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022). The participant sample for this study had a higher representation of non-Hispanic White individuals (83.4%) compared to the Northeastern average (63%). As a result, the research team has considered this overrepresentation in the analysis, as it may influence the generalizability of the results to more diverse populations.

Quantitative results were analyzed among participants who shared their geographic location to compare rural vs urban responses with the limitation of excluding those who did not give further detail of their living status. Our results indicated no statistical difference between rural and urban groups in any of the selected survey questions. Chi-square analysis was used to compare yes/no answers for questions regarding diagnosis-related functional impairments and feelings of welcome or exclusion. Binary logistic regression modeling was used to analyze the relationship between support and resource attainment from participants and the level of impairment from their disability (or the disability of the person they care for). Tables 2 and 3 display results from the binary logistic regression and chi-square analysis. Because there were no quantitative differences among the groups analyzed, the authors determined that the open responses would be qualitatively analyzed without group separation of geographic descriptors.

| 95% CI for odds ratio | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | Β | SE | Sig. | Odds | Lower | Upper |

| How much difficulty do you have seeing, even if wearing glasses? | 0.032 | 0.129 | 0.805 | 1.032 | 0.802 | 1.329 |

| How much difficulty do you have hearing, even if using a hearing aid? | -0.103 | 0.153 | 0.501 | 0.902 | 0.668 | 1.218 |

| How much difficulty do you have walking or climbing stairs? | -0.017 | 0.122 | 0.889 | 0.983 | 0.774 | 1.249 |

| How much difficulty do you have remembering or concentrating? | 0.079 | 0.140 | 0.573 | 1.082 | 0.822 | 1.425 |

| How much difficulty do you have with self-care such as washing all over or dressing? | 0.136 | 0.155 | 0.381 | 1.146 | 0.845 | 1.554 |

| How much difficulty do you have communicating, for example understanding or being understood by others? | -0.077 | 0.146 | 0.600 | 0.926 | 0.696 | 1.233 |

| Can you get the services or supports you need? | 0.214 | 0.216 | 0.322 | 1.238 | 0.811 | 1.890 |

| Geographic setting | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Response | Rural | Urban | Value | df | Sig. |

| Are there communities, groups, or places in Vermont where you feel welcome? | Yes | 41 | 47 | 1.29 | 1 | 0.256 |

| No | 5 | 11 | ||||

| Are there communities, groups, or places in Vermont where you feel excluded? | Yes | 32 | 40 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.918 |

| No | 13 | 17 | ||||

Qualitative Results

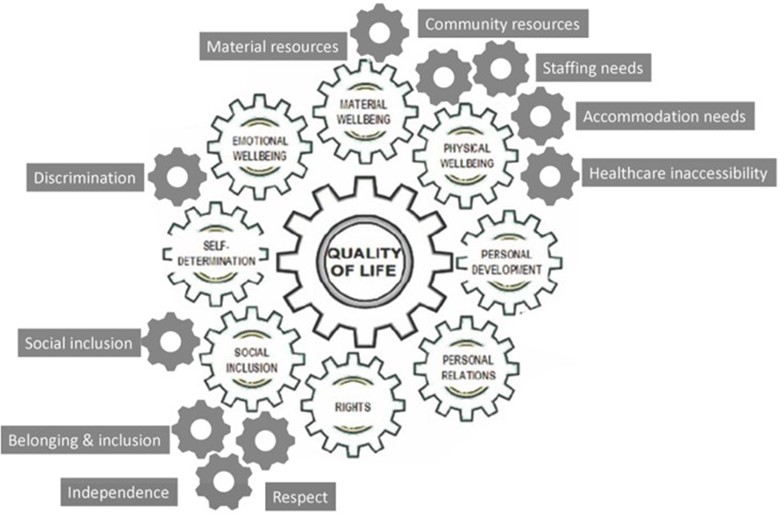

All open-ended survey responses to the questions: “What are the top needs for people with disabilities in Vermont?” and “What are the biggest barriers for people with disabilities in Vermont?” were analyzed using thematic coding to assess the qualitative data regarding lived experience. Once themes were identified, results were cross-compared with Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) domain descriptions and indicators. The themes and sub-themes identified were then corresponded to the appropriate domains of the guiding model. The domains of the model were not considered or analyzed before initial thematic coding to limit bias in establishing codes and occurring themes. As the sub-themes were matched to Schalock and Verdugo’s model after theme iteration, not all QoL domains have an identified sub-theme from our dataset. This further validated the application of this model to a moderately sized sample within this population. We further argue the applicability of this model to our analyzed population as the thematic coding results aligned with the descriptions and applications of the eight domains of the selected framework based on the descriptions provided by their original authors. Figure 2 integrates the QoL model with the sub-themes that emerged from our qualitative analysis. Sub-themes are placed strategically near the original framework domains with which they align.

Three qualitative themes were identified: (1) values; (2) resources; and (3) accessibility and competence. Each theme additionally had 3 to 4 sub-themes that were contextualized through the thematic analysis of all open-ended participant responses. Table 4 juxtaposes some of the participant responses for each of the three themes, separated by participant type (rural vs. urban). There were no identifiable differences among urban and rural respondents in identifying barriers and needs within this IDD and care partner community. However, many respondents, from both rural and urban areas, reported that rural residents with IDD faced increased barriers to accessing resources.

| QoL framework domain/participant | Quote |

|---|---|

| Values: Reported high-need items for participants with disabilities in Vermont most often relate to value discrepancies between persons with disabilities and the larger community. Sub-themes from participant data here include belonging and inclusion, respect, and independence. The theme and sub-theme for VALUES correlate with domains of rights and social inclusion. | |

| Rural-dwelling participants | “Recognition as Vermont citizens whose basic human rights need to be respected and attended to.”

“Access to the same rights and privileges as able-bodied people. Having a voice; having their needs heard and accommodated.” |

| Urban-dwelling participants | “Many people in our communities still see people with disabilities as less, as a burden, as not having the same value as others without disabilities. These biases are held by some of our educators, employers, legislators, community-leaders and continue to create experiences in which people with disabilities are not getting what they need.”

“I think that the top needs for people with disabilities in Vermont are to be cared for, not be judged by whatever their disability may be, and have a great life even with their condition.” |

| >Resources: Resources at a personal and community level dramatically impact the ability of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to engage in the community context. Sub-themes from participant data here include material resources, community resources, social resources, and staffing needs. The theme and sub-themes for RESOURCES correlate with domains of material well-being, physical well-being, and social inclusion. | |

| Rural-dwelling participants | “They need to have stable, supportive housing choices. Not just the shared living provider system that is their only choice now. That’s just foster care. If the SLP system doesn’t work for them, their only choice is to move back in with their exhausted and elderly parents. Not a good situation. We need staffed, permanent, places for folks.”

“Workers. Any workers- but particularly skilled workers. Housing- convoluted over regulated housing subsidies and systems. Lack of community inclusion which the system of care actually interferes with as services are attached to staff presence- still lots of caretaking and babysitting. In home care for those more seriously disabled with complex medical needs.” |

| Urban-dwelling participants | “Adults with ID/DD need stable housing with services. There are no choices in housing for high needs adults with ID/DD, the only ‘option’ is the shared living provider model, which is adult foster care, providing little to no stability. These vulnerable adults are a high risk of homelessness when their elderly parents can no longer care for them.” |

| (table continues) | |

| “Transportation is the most important thing. If you can’t get to appointments, can’t get to supplies, can’t get to opportunities to have leisure. . . you can’t live in Vermont.”

“Lack of social interactions are also a major problem since disabled people can’t just hop in a car and drive to their friends or family to visit, which may force them to electronic interaction only unless a plan to meet with their friends is made far enough in advance.” |

|

| Accessibility and competency: Participants shared how accessibility in a community and statewide context was explicitly and implicitly connected to reduced participation overall. Sub-themes from participant data here include accommodation needs, discrimination, healthcare inaccessibility, and staffing competency needs. The theme and sub-themes for Accessibility and Competency correlate with domains of interpersonal relationships, emotional well-being, physical well-being, self-determination, and personal development. | |

| Rural-dwelling participants | “People with disabilities often get support for one issue then once the box is checked there is no follow up. It seems like every new provider in health (medical/behavioral/dental) all require a vast knowledge of information to be added to their portal before an appointment. Businesses are making a push for self checkout – when systems remove support people, it makes the journey to get daily life activities more complicated.” |

| Urban-dwelling participants | “… only once have I been on a bus where the driver puts the ramp for someone with a mobility aid. This tells me that people are stuck in their homes, and not getting out and about in the world … But this is such a rural state, and I worry about all the people I don’t see.”

“Discrimination -especially by employers, employers screen out the disabled by requiring driver’s licenses/own car for a job where that is not an essential part of the job.” |

Discussion

This secondary data analysis was an opportunity to hear directly from individuals with IDD and their care partners in a very rural state in the U.S. This paper uses the term “care partner” as compared with carer or caregiver to better define an active care relationship between the person with the diagnosis and the significant people in their lives. This concept acknowledges that people play a key and active role in their care and may have multiple people within the context of their lives who may assist them with their activities of daily living. This also allows for a wider diversity in care-defined relationships inclusive to family members and romantic partners in comparison with sole guardians and parents as often assumed in the term “caregiver” (Bennett et al., 2017). Our findings present a unique circumstance given the rurality of the state and population sampled compared with the general population. This paper sought out to further understand the potential discrepancies regarding perceived disparities between rural and urban-dwelling people with IDD and their care partners. This paper also intended to analyze and interpret whether Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) framework held ecological validity with a primarily rural sample population. The following discussion will critically evaluate how and to what extent these aims were assessed within this analysis’s context.

This paper’s main aim was to investigate potential disparities between people with IDD living in rural and urban areas. The results of both the quantitative and qualitative measures did not reveal differences between groups. We found that urban and rural-dwelling people with IDD and their care partners shared similar challenges in obtaining resources, including staff, accessing medical care, and receiving opportunities for community integration. These findings seem in contrast with previous studies that found that rurality and geographic distancing contribute to depleted resource access and poorer health outcomes (Fortney & Tassé, 2021; Probst et al., 2019). Given the sample for this study, with only one urban county within a primarily rural state surveyed, it is plausible that the survey respondents living in the urban setting may be also facing similar resource disparities as their rural counterparts. With this knowledge, disability researchers must consider that many of the resource disparities noted may be due to rurality alone but more likely, due to the intersection of rurality and disability status. This study only focused on the investigation of the intersection of these two. It is critical, therefore, that future studies examine not just the intersection of the two factors or rurality status at the town or city level, but also the state or region. Because of the nature of these state and context-specific results, it is equally important to further research correlational, but not necessarily causal, relationships among the factors described in our qualitative findings that drive these disparities beyond mere population density alone (i.e., reduced access to diagnosis and informed medical care, reduced social programming, etc.). Therefore, the needs of those who have an IDD or are a care partner to someone with the diagnosis can be better addressed by completing more thorough needs assessments at the local, state, and national levels to reduce possible inaccurate generalizations of urban vs rural resource disparities as demonstrated by our sample in the primarily rural state of Vermont. This may inform program development and policymakers to better address the more nuanced needs of communities despite their population density as this may be only one of many factors affecting resource access in more rural states in the Northeast region and beyond.

The secondary aim of this paper was to apply an already developed QoL construct and model in the IDD literature to the sampled population to assess its ecological validity. While the applicability of this model was evaluated in a small, region-specific population, the natural convergence of the qualitative themes to the described domains demonstrated some universality of lived experience and QoL factors in people with IDD and their care partners. This demonstrates an opportunity for greater use of Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) model in contexts pertaining to the Vermont IDD population further in policy and program development aimed at improving QoL. In addition, the described experiences in our qualitative findings often matched the direct descriptions of the model’s domains and their subsequent indicators which highlighted that the resource needs of people with IDD in Vermont are directly related to IDD QoL. It should be noted, however, that not all QoL domains from the assessed model have a corresponding sub-theme identified through our qualitative investigation. The sub-themes associated with Schalock and Verdugo’s QoL domains further highlight some of the challenges reported by people with IDD and their care partners in a primarily rural state. For example, access to affordable and accessible healthcare is essential for physical well-being and health promotion as well as optimal QoL (Bacherini et al., 2024). Inaccessibility of the healthcare system was a common response for both urban and rural-dwelling members of the disability community surveyed. Therefore, this sub-theme of “healthcare inaccessibility” is appropriately positioned next to physical well-being considering its direct contribution to QoL in this capacity and is a topic that needs to continue to be addressed within scholarly research. Conversely, there are no sub-themes from our assessed dataset that are positioned next to the domain of ‘personal development.’ This does not mean personal development isn’t an important contributor to QoL for people with IDD or is something that is relevant for people with IDD living in a rural state. The two qualitative questions analyzed focused on top needs and biggest barriers for this population and personal development were not highlighted through our sub-themes and participant responses. The contribution of our developed sub-themes to already existing domains on QoL prompts discussion on the intersectionality of rural QoL, IDD, and how values, perceived resource needs, and attitudes towards disability may differ in states that are less populous than primarily urban-centered states within the country.

The suitability of Schalock and Verdugo’s model, which was developed for individuals with IDD specifically, comes from both universal (etic) and culture-bound (emic) properties previously described in the literature (Schalock et al., 2005; Verdugo et al., 2001). These properties come from international and cross-cultural validation studies identifying this model as both a conceptual and measurement framework (Jenaro et al., 2005; Schalock, 2004; Schalock et al., 2005; Verdugo et al., 2001). The universality of the domains describes areas of life and living inherent to the QoL of those with IDD universally, regardless of location. However, the rurality of this sampled population demonstrates the specific culture-bound properties living in a primarily rural state has on individual and community characteristics that may affect these more universal experiences for people with IDD. For example, the domain of “Rights” is a universal domain for individuals with IDD, yet the following survey response highlights a more rurally focused indicator in response to “What are the top needs for people with disabilities living in Vermont?”:

Varied opportunities to engage that acknowledge we are a rural, geographically challenged state. This means – multiple opportunities should support/engage smaller communities across the state.

However, there are experiences for individuals with IDD and their care partners in the findings, which may be more representative of the universal (etic) properties of IDD QoL. Wait times were expressed by respondents often in this study, one quote noting:

Access to resources, PT/OT/SLP are extremely limited in the private sector and those in the school system are serving so many they don’t have time to fulfill the needs of students. We aren’t helping families get the support they need.

The literature notes that this was a common experience for those with IDD, such as the wait times for primary care services and specialized providers, which may contribute to the validity of the etic properties of the framework (Doherty et al., 2020; Lunsky et al., 2007). These two examples demonstrate that many of the effects on IDD QoL in this rurally sampled population are, universal to the experience of IDD, but many have nuance to the experiences of rural areas affected by the geographic distancing of resources and staff needed to improve QoL.

Because of the lack of literature directly highlighting rural experiences for people with IDD and their care partners in the context of QoL, there may be additional discrepancies within the responses of this survey and its applicability to the overall QoL framework highlighted in this paper. The literature broadly defines a lack of resources, skilled care providers, and reduced knowledge of the care of individuals with IDD but without the specific acknowledgment of the rural lived experience (Johnston et al., 2022; Malik-Soni et al., 2022). The importance of bridging the gap between rural IDD populations and current QoL research is considered of utmost importance to improve future research endeavors, resource access, and program development. Overall, our qualitative findings of this population and their care partners did apply to the current QoL framework acclaimed within current IDD literature. Based on the applicability of Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) framework domains to the responses of the survey, further face and ecological validity can be applied to this smaller, rural population with the potential for greater generalizability with future research. Specifically, in more rural settings.

In addition, QoL and resource attainment may also be influenced by the functional independence of people with IDD and positive community attitudes and feelings of belonging as compared with sole resource availability in a community regardless of rurality status (Bramston et al., 2002; Merrells et al., 2018; Pretty et al., 2002). Our findings contribute to the literature in the perspective that this population’s needs may require enhanced resource and program development in urban and rural settings to meet their greater needs.

Our findings also demonstrate agreement with the literature on the resource needs and additional disparities of rural IDD populations. Specifically, how they affect IDD QoL. However, our urban-county respondents noted parallel resource needs and attitudinal barriers which may be impacted by the overall rurality of the geographic area surveyed. This creates a call for future research to explore the needs of rural states overall and their unique contexts for resource needs of people with IDD and their support systems.

Limitations

Limitations of this current study include the deficits with using survey questions not aimed at the original research questions and hypotheses of this secondary analysis. This created barriers in selecting questions that could be analyzed and question designs that could increase power within the quantitative analysis between groups. Also, the open response format of the survey and its original design did not allow required responses from users, creating gaps in data between questions and between respondents that reduced overall power in analyzing the sample. This also meant survey respondents did not need to share their geographic location which created an additional gap in the quantitative data that could have given a more thorough review of geographic implications on responses from participants. Survey design also limited the ability to discern diagnosis labels from care partners themselves or the person they worked with, or both. It is also important to note that participants were self-selected to complete the survey. While the gender, age, and race of participants were like the state as a whole, it was still a convenience sample and not necessarily representative of experiences in the state. The generalizability of results was then limited by these parameters, however, there existed uniformity in responses across all groups in both quantitative and qualitative data indicating a need for further research and evaluation of this intersection of urbanicity in a primarily rural area.

The second aim of this study was to assess the ecological validity of Schalock and Verudgo’s QoL model to a primarily rural population. While study findings indicate applicability of this model adapted to a rural population, a few other measures could have been taken by the research team, such as including persons with lived experience as part of the research team or increasing the number of descriptive statistics retrieved to enhance the representativeness of real-world events and increase ecological validity overall (Fahmie et al., 2023). To date, there is no concrete method for assessing ecological validity in study designs, however, these may be spaces for improvement and a more honed focus on ecological validity in future studies.

Conclusion

The findings from this secondary analysis show the importance of intentionally addressing the QoL for people with IDD and their care partners in both rural and urban communities. When comparing resource needs, challenges, impairments, or sense of belonging, our results indicated no statistical difference between urban and rural groups. This further emphasizes the importance of learning more about the challenges and barriers faced by this population and exploring rurality in more nuanced ways. This study contributes novel findings to add to current IDD literature for those living in more rural settings. Additionally, this study brings forward the applicability of an IDD QoL framework cited in the current literature to a sample population with unique rural features. Adding ecological validity to these frameworks and models developed within the field allows for further research to be developed or improved through the parameters and domains of models that can be applied to the general population being analyzed; in this study and current example, this pertains to those with IDD and their care partners.

Future research should continue investigating the rural-urban divide and, specifically, the QoL for this population. By focusing research on studying these gaps and developing targeted interventions or strategies to enhance resource availability and mitigate negative effects, we hope that the QoL for people with IDD and their care partners can be better understood and meaningfully improved.

References

Andrade, C. (2018). Internal, external, and ecological validity in research design, conduct, and evaluation. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 40(5), 498-499. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpsym.ijpsym_334_1

Bacherini, A., Gómez, L. E., Balboni, G., & Havercamp, S. M. (2024). Health and health care are essential to the quality of life of people with intellectual disability. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 21(2), e12504. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12504

Baernholdt, M., Yan, G., Hinton, I., Rose, K., & Mattos, M. (2012). Quality of life in rural and urban adults 65 years and older: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination survey. The Journal of Rural Health, 28(4), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00403.x

Beadle-Brown, J., Murphy, G., & DiTerlizzi, M. (2009). Quality of life for the Camberwell Cohort. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22(4), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00473.x

Bennett, P. N., Wang, W., Moore, M., & Nagle, C. (2017). Care partner: A concept analysis. Nursing Outlook, 65(2), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2016.11.005

Bonham, G., Basehart, S., Schalock, R., Marchand, C., Kirchner, N., & Rumenap, J. (2004). Consumer-based quality of life assessment: The Maryland Ask Me! Project. Mental Retardation, 42, 338–355. https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2004)42%3C338:cqolat%3E2.0.co;2

Bramston, P., Bruggerman, K., & Pretty, G. (2002). Community perspectives and subjective quality of life. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 49(4), 385–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 1034912022000028358

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Caudill, A., Hladik, L., Gray, M., Dulaney, N., Barton, K., Rogers, J., Noblet, N., & Ausderau, K. K. (2022). Health narratives as a therapeutic tool for health care access for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2022.2099603

Dassah, E., Aldersey, H., McColl, M. A., & Davison, C. (2018). Factors affecting access to primary health care services for persons with disabilities in rural areas: A “best-fit” framework synthesis. Global Health Research and Policy, 3(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-018-0091-x

Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). (2021). Vermont—2021—III.B. Overview of the State. https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/Narratives/Overview/915a8107-b190-47b8-9290-ef01c07d1381

Doherty, A. J., Atherton, H., Boland, P., Hastings, R., Hives, L., Hood, K., James-Jenkinson, L., Leavey, R., Randell, E., Reed, J., Taggart, L., Wilson, N., & Chauhan, U. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to primary health care for people with intellectual disabilities and/or autism: An integrative review. BJGP Open, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen20X101030

Ervin, D. A., Hennen, B., Merrick, J., & Morad, M. (2014). Healthcare for persons with intellectual and developmental disability in the community. Frontiers in Public Health, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00083

Fahmie, T. A., Rodriguez, N. M., Luczynski, K. C., Rahaman, J. A., Charles, B. M., & Zangrillo, A. N. (2023). Toward an explicit technology of ecological validity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 56(2), 302-322. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.972

Fortney, S., & Tassé, M. J. (2021). Urbanicity, health, and access to services for people with intellectual disability and developmental disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 126(6), 492–504. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-126.6.492

Hussain, R., & Tait, K. (2015). Parental perceptions of information needs and service provision for children with developmental disabilities in rural Australia. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(18), 1609–1616. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.972586

Jenaro, C., Verdugo, M., Caballo, C., Balboni, G., Lachapelle, Y., Otrebski, W., & Schalock, R. (2005). Cross-cultural study of person-centered quality of life domains and indicators: A replication. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 734–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00742.x

Johnston, K. J., Chin, M. H., & Pollack, H. A. (2022). Health equity for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of the American Medical Association, 328(16), 1587–1588. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.18500

Kelly, D., Schroeder, S., & Leighton, K. (2022). Anxiety, depression, stress, burnout, and professional quality of life among the hospital workforce during a global health pandemic. The Journal of Rural Health, 38(4), 795–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12659

Kyonka, E. G., & Subramaniam, S. (2018). Translating behavior analysis: A spectrum rather than a road map. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 41(2), 591–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-018-0145-x

Larson, S. A., Neidorf, J., Pettingell, S., & Sowers, M. (2023). Long-term supports and services for persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities: Status and trends through 2019. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.23116.08320

Laurence, T., & Wendy, C. (2014). Health Promotion for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. McGraw-Hill Education.

Lewkowicz, D. J. (2001). The concept of ecological validity: What are its limitations and is it bad to be invalid? Infancy, 2(4), 437-450. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327078in0204_03

Lunsky, Y., Garcin, N., Morin, D., Cobigo, V., & Bradley, E. (2007). Mental health services for individuals with intellectual disabilities in Canada: Findings from a national survey. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20(5), 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2007.00384.x

Madans, J. H., Loeb, M. E., & Altman, B. M. (2011). Measuring disability and monitoring the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: The work of the Washington Group on Disability Statistics. BMC Public Health, 11(4), S4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-S4-S4

Malik-Soni, N., Shaker, A., Luck, H., Mullin, A. E., Wiley, R. E., Lewis, M. E. S., Fuentes, J., & Frazier, T. W. (2022). Tackling healthcare access barriers for individuals with autism from diagnosis to adulthood. Pediatric Research, 91(5). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01465-y

Merrells, J., Buchanan, A., & Waters, R. (2018). The experience of social inclusion for people with intellectual disability within community recreational programs: A systematic review. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 43(4), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2017.1283684

Moss, J. L., Pinto, C. N., Mama, S. K., Rincon, M., Kent, E. E., Yu, M., & Cronin, K. A. (2021). Rural–urban differences in health-related quality of life: Patterns for cancer survivors compared to other older adults. Quality of Life Research, 30, 1131–1143. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11136-020-02683-3

National Institute of Health (NIH). (2021, November 9). About intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs). https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/idds/conditioninfo

Office of the Surgeon General, & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2002). Closing the gap: A national blueprint to improve the health of persons with mental retardation. Report of the surgeon general’s conference on health disparities and mental retardation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44346/

Pretty, G., Rapley, M., & Bramston, P. (2002). Neighbourhood and community experience, and the quality of life of rural adolescents with and without an intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 27(2), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250220135079-5

Probst, J., Eberth, J. M., & Crouch, E. (2019). Structural urbanism contributes to poorer health outcomes for rural America. Health Affairs, 38(12), 1976–1984. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00914

Richman, L., Pearson, J., Beasley, C., & Stanifer, J. (2019). Addressing health inequalities in diverse, rural communities: An unmet need. SSM-Population Health, 7. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00914

Schalock, R. L. (2000). Three decades of quality of life. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 15(2), 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/108835760001500207

Schalock, R. L. (2004). The concept of quality of life: What we know and do not know. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 48(3), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2003.00558.x

Schalock, R. L., Bonham, G. S., & Verdugo, M. A. (2008). The conceptualization and measurement of quality of life: Implications for program planning and evaluation in the field of intellectual disabilities. Evaluation and Program Planning, 31(2), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.02.001

Schalock, R. L., Gardner, J. F., & Bradley, V. J. (2007). Quality of life for people with intellectual and other developmental disabilities: Applications across individuals, organizations, communities, and systems. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Schalock, R. L., & Verdugo, M. A. (2002). Handbook on quality of life for human service practitioners. American Association on Mental Retardation.

Schalock, R. L., Verdugo, M. A., Jenaro, C., Wang, M., Wehmeyer, M., Jiancheng, X., & Lachapelle, Y. (2005). Cross-cultural study of quality of life indicators. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 110(4), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110[298:CSOQOL]2.0.CO;2

Schalock, R., Verdugo, M., Jenaro, C., Wang, M., Wehmeyer, M., Jiancheng, X., & Lachapelle, Y. (2005). Cross-cultural study of quality of life indicators. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 110, 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110[298:CSOQOL]2.0.CO;2

Simões, C., & Santos, S. (2016). The quality of life perceptions of people with intellectual disability and their proxies. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 41(4), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2016.1197385

Stein, E. M., Gennuso, K. P., Ugboaja, D. C., & Remington, P. L. (2017). The epidemic of despair among White Americans: Trends in the leading causes of premature death, 1999–2015. American Journal of Public Health, 107(10), 1541–1547. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303941

Townsend-White, C., Pham, A. N. T., & Vassos, M. V. (2012). Review: A systematic review of quality of life measures for people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviours. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56(3), 270–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01427.x

U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Census Reporter: Northeast Region. http://censusreporter.org/profiles/02000US1-northeast-region/

Verdugo, M. A., Schalock, R. L., Wehmeyer, M. L., Caballo, C., & Jenaro, C. (2001). Cross-cultural survey of quality of life indicators. Salamanca: Institute on Community Integration, Faculty of Psychology, University of Salamanca.

Wang, M., Schalock, R. L., Verdugo, M. A., & Jenaro, C. (2010). Examining the Factor Structure and Hierarchical Nature of the Quality of Life Construct. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 115(3), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-115.3.218

Washington Group on Disability Statistics. (n.d.). WG Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS). https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/question-sets/wg-short-set-on-functioning-wg-ss/

Williams, K., Jacoby, P., Whitehouse, A., Kim, R., Epstein, A., Murphy, N., Reid, S., Leonard, H., Reddihough, D., & Downs, J. (2021). Functioning, participation, and quality of life in children with intellectual disability: An observational study. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 63(1), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14657

Yen, I. H., Michael, Y. L., & Perdue, L. (2009). Neighborhood environment in studies of health of older adults: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(5), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.022