Applying a Framework of Epistemic Injustice to Understand the Impact of COVID-19 on People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

Sarah Lineberry and Matthew Bogenschutz

Lineberry, S., & Bogenschutz, M. (2024). Applying a framework of epistemic injustice to understand the impact of COVID-19 on people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 4(2), 80-101. https://doi.org/10.59620/2694-1104.1090

Plain Language Summary

Epistemic injustice is a way of explaining why some people are not listened to or believed. Epistemic injustice often occurs because of false beliefs about groups of people. These beliefs can lead to people being mistreated or excluded. People with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) might experience epistemic injustice. We reviewed research about COVID-19 to understand how the pandemic affected people with IDD. We also looked at how epistemic injustice might have influenced these outcomes. We found that people with IDD may have been more likely than people without IDD to get very sick or die from COVID-19. We also found that many people with IDD experienced changes to their daily routines and services. These changes may have caused negative mental health outcomes. We can use epistemic injustice to understand these findings and make policies that better include people with IDD.

Abstract

Epistemic injustice, the theory of unfairness related to knowledge, is a useful framework for understanding the ways in which historic and ongoing marginalization and stereotypes have shaped the ways that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. We conducted a scoping review of the literature and divided findings into physical health (cases, hospitalization, and death) and psychosocial outcomes (access to services, mental health symptoms, community participation, etc.). Impacts were then analyzed using the key principles of epistemic injustice. Findings suggest that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) experienced high rates of negative physical health and psychosocial outcomes from the COVID-19 pandemic compared to people without disabilities and that epistemic injustice could be used to understand these impacts in a broader context.

Introduction

Intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) refer to a range of conditions that begin before adulthood and affect cognition and adaptive functioning (Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 2000, 42 U.S.C. §1500; Schalock et al., 2019). Approximately 2.27% of people in the U.S. have an intellectual and/or developmental disability, totaling about 7.3 million people (Larson et al., 2020). Evidence suggests that people with IDD may be particularly vulnerable in public health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to the general population. People with IDD may be at increased risk of contracting COVID-19 (Gleason et al., 2021), particularly if they live in congregate settings (Landes et al., 2020). Furthermore, people with IDD who contract the virus may be at higher risk of hospitalization (Gleason et al., 2021) and death (FAIR Health, 2020; Gleason et al., 2021; Landes et al., 2020; Spreat et al., n.d.).

Despite these documented adverse outcomes, people with IDD were largely overlooked or discriminated against in the U.S. response to the pandemic. For example, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) did not issue guidance related to group homes for people with IDD until May 2020, more than 4 months after cases were first reported in the U.S., despite evidence that these settings put people at heightened risk for contracting the virus (Landes et al., 2020). When official guidance was developed, it often discriminated against people with disabilities and chronic health conditions. For example, many state and medical system guidelines stated that people with certain disabilities, support needs, or chronic health conditions should not be prioritized for high-intensity care in the case of a shortage of resources (Center for Public Representation [CPR], 2020).

In addition to discriminatory treatment allocation systems, research suggests that people with IDD were rarely prioritized in state vaccination campaigns (Hotez et al, 2021). While people living in congregate care settings, including group homes for people with IDD, and people with some specific conditions, including Down Syndrome, were prioritized early (Hotez et al., 2021), a review conducted in early 2021 found that only 10 states prioritized people with other physical, intellectual, and/or developmental disabilities (Jain et al., 2021). This deprioritization may be partially attributed to the lack of data about health outcomes for people with IDD and other disabilities (Hotez et al., 2021; Wiggins et al., 2021).

Fricker’s (2007) theory of epistemic injustice, in combination with Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) social ecological model can help to identify the marginalization of people with IDD in the COVID-19 pandemic response at the interpersonal, organizational, and societal levels. This paper uses the social ecological model to organize findings from a scoping review of the early literature about the impact of COVID-19 on people with IDD and to apply the theory of epistemic injustice as a guiding framework to better understand these findings.

Epistemic Injustice

The theory of epistemic injustice was proposed by Fricker (2007) as unfairness related to knowledge to make sense of the injustice they experience and the philosophical implications of powerlessness (Fricker, 2017). This theory posits that some people are dismissed as knowers because of some part of their identity which, by extension, limits the collective understanding of their experiences. In this way, people with epistemic privilege control the topics of research and knowledge, thereby perpetuating injustice and marginalization. Specifically, Fricker (2007) divided epistemic injustice into two categories: testimonial injustice and hermeneutical injustice. Testimonial injustice occurs when an individual is not considered a credible witness because of some personal characteristic or membership in a marginalized group (Fricker, 2007; Young et al., 2019). In instances of testimonial injustice, prejudice against a person leads them to be viewed as unreliable and less likely to be listened to or believed (Fricker, 2007, 2017).

While testimonial injustice describes a situation where stereotypes and assumptions prevent a person from being believed, hermeneutical injustice describes a difficulty in understanding and sharing one’s experiences due to a gap in the collective knowledge (Fricker, 2007, 2017). Oftentimes, this knowledge gap exists because the experiences of marginalized groups do not fit with existing concepts and are not considered appropriate subjects of research (Bhakuni & Abimbola, 2021; Fricker, 2007). For example, research often prioritizes the interests of funders or the perspectives of dominant social groups, rather than the interests and needs of a marginalized community (Bhakuni & Abimbola, 2021). Research that does not center the voices of the community may perpetuate prejudicial assumptions and marginalization (Bhakuni & Abimbola, 2021). Bhakuni and Abimbola propose calling this type of wrong “interpretive injustice” to be more accessible to a wider audience.

It should be noted that the theory of epistemic injustice has been critiqued by some disability researchers. For example, Catala (2020) argues that the original conceptualization of epistemic agency as “the ability to produce, convey, or use knowledge” is too narrowly defined and excludes many people with IDD (p. 756). Specifically, Catala points out that Fricker’s (2007) use of “speaker” and “hearer” to designate roles in the communication process centers verbal communication and ignores people who do not communicate using spoken language. Similarly, epistemic injustice overly emphasizes propositional knowledge and reasoning above other ways of knowing (Catala, 2020). Despite these criticisms, epistemic injustice is a useful framework for exploring the experiences of people with IDD during the COVID-19 pandemic specifically and health disparities more broadly by explicitly naming the intellectual and moral wrongs that place people with IDD at heightened risk (Fricker, 2007).

Social Construction of Intellectual Disability

In her examination of epistemic injustice, Fricker (2007) emphasizes the importance of understanding the cultural and historical settings, social constructions, and prejudices of a group to identify and correct for biases and gaps in knowledge. Before we can apply Fricker’s theory to an examination of the existing research on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with IDD, we must first understand the historic, social, and structural factors that have shaped the concept of intellectual disability in the U.S.

From at least the 18th century, people with IDD have been considered less worthy of study and care than people without disabilities (see Abbas, 2016; Goodey, 2001; Siebers, 2008; Trent, 2016). These pervasive conceptualizations about disability may have made people with IDD particularly vulnerable to a public health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic (Hotez et al., 2021; Wiggins et al., 2021). As Fricker (2007) points out, negative stereotypes do not need to be believed to have an impact. Instead, these innate biases “more surreptitiously” discredit marginalized groups and work to maintain the existing societal power structures (Fricker, 2007, p. 98). While attitudes and policies towards people with IDD have shifted dramatically since the 1970s (Wehmeyer & Schalock, 2013), historical prejudices and models of disability continue to inform policy and practices today (Guevara, 2021).

While Fricker’s original theory of epistemic injustice did not explicitly include people with IDD, many of the concepts from her theory can be applied to the historical treatment and conceptualization of people with IDD and other disabilities. Until recently, people with disabilities were kept out of sight from most people, using institutional living arrangements completely separated from the community (Wehmeyer & Schalock, 2013). This physical separation allowed for people with disabilities to be kept out of sight epistemically as well, so that the experiences and knowledge of people with IDD may not be considered important by the broader community (Scully, 2018). Furthermore, people with IDD are often seen as having limited credibility and are not given the opportunities to share their experiences as knowers and knowledge creators (Kalman et al., 2016).

Epistemic Injustice and Healthcare

For this paper, understanding the relationship between epistemic injustice and health is especially important. Medical providers are epistemically privileged in that they are experts by virtue of their training and social position (Carel & Kidd, 2014; Peña-Guzmán and Reynolds, 2019). While this privilege is clearly merited in clinical decision making, it can come at the expense of patients’ own expertise (Carel & Kidd, 2014; Iezzoni et al., 2021; Peña-Guzmán and Reynolds, 2019). For instance, epistemic injustice at medical appointments means that patients, particularly people with chronic illnesses, psychiatric conditions, or disabilities, are frequently ignored as unreliable, even when describing their own experiences, impeding effective communication (Carel & Kidd, 2014; Iezzoni et al., 2021; Peña-Guzmán and Reynolds, 2019). In contrast, Carel and Kidd argue that epistemic justice in healthcare would respect the diverse epistemic privileges of patients and providers, informed by social power and hierarchy in treatment settings, so that providers are the experts in clinical assessments and diagnostics and patients are the experts in their own experiences.

The harms of testimonial injustice in interactions between healthcare providers and patients can be compounded by hermeneutical injustice. Research suggests that many providers have insufficient knowledge of intellectual disabilities and associated health conditions, due to both a lack of formal education about disabilities and a lack of exposure to people with IDD (Krahn et al., 2006; Pelleboer-Gunnink et al., 2017; Wilkinson et al., 2012). In the absence of needed information, providers may rely on stereotyped assumptions of patients with IDD (Krahn et al., 2006; Pelleboer-Gunnink et al., 2017; Wilkinson et al., 2012).

Beyond the epistemic harm of being ignored and excluded, epistemic injustice in medicine can have dire consequences for patients’ health (Carel & Kidd, 2013; Iezzoni et al., 2021; Peña-Guzmán & Reynolds, 2019). Diagnostic overshadowing is a well-documented example of the negative impact of testimonial injustice among doctors treating patients with IDD, wherein symptoms and behaviors are ascribed to the disability, rather than to an unrelated medical condition (Peña-Guzmán & Reynolds, 2019; While & Clarke, 2010). In these situations, a provider’s overreliance on their own stereotyped beliefs about disability can delay treatment for physical health conditions (Carel & Kidd, 2014; Peña-Guzmán & Reynolds, 2019; While & Clarke, 2010).

The theory of epistemic injustice has also been used to identify injustices in academic global health research. Bhakuni and Abimbola (2021) argue that academic researchers have historically excluded local experts from the process of knowledge creation. Again, this injustice has both epistemic and practical implications. From a strictly epistemic perspective, local researchers and practitioners are denied the opportunity to generate knowledge (Bhakuni & Abimbola, 2021). From a practical and moral perspective, excluding local experts may lead to prejudicial assumptions and ineffective interventions that perpetuate existing health inequities (Bhakuni & Abimbola, 2021).

Research Questions

This study sought to answer two main research questions.

- What were the physical health, mental health, and psychosocial impacts of COVID-19 on people with IDD during the first two years of the pandemic? This research question was developed in accordance with the “PCC” mnemonic (population, concept, and context) recommended by the JBI Scoping Review Methodology Group (Peters et al., 2020).

- How does Fricker’s (2007) theory of epistemic injustice present in and add meaning to the literature about the impacts of COVID-19 on people with IDD?

Moving forward, equitable research and public health responses depend on critically interrogating who is centered in and excluded from research and knowledge creation, and the ways that such exclusion can perpetuate ongoing marginalization and poor health outcomes for people with IDD.

Methods

This study was conducted in two stages. First, the authors conducted a scoping review to better understand the impacts of this pandemic on the physical health, mental health, and psychosocial outcomes of people with IDD, using methodology suggested by Peters et al. (2020). We then analyzed the identified articles using Fricker’s (2007) framework of epistemic injustice to explain the marginalization and disproportionate impact of the pandemic on this population.

Given that this review was exploratory in nature and sought to understand the general state of knowledge about the impact of COVID-19 on people with IDD, a scoping review was deemed to be appropriate methodology (Peters, et al., 2020).

The search was conducted in April 2022 for articles published from January 2020 through April 2022. Articles were identified through a search of Academic Search Complete, PubMed, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) databases, using search criteria developed to match the research question and the PCC mnemonic (Peters et al., 2020). The search terms included “intellectual disability OR developmental disability” AND “covid-19 or coronavirus or 2019-ncov or sars-cov-2 or cov-19” AND “prognosis OR outcome OR incidence OR fatality.” The reference lists of articles that met inclusion and exclusion criteria (described below) were reviewed for additional studies. Finally, the “cited by” feature of Google Scholar was used to identify recent articles citing any included article. Google Scholar was needed to identify articles that had not yet been indexed in the databases used in the search of the three major indexes noted above.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles were included if they were published in English in a peer-reviewed journal and described the outcomes of people with IDD in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. International studies that included a U.S. sample were included in article selection, but data extraction and analysis only considered results from the U.S. Given the rapidly changing landscape and the relative paucity of research in this field, “outcome” was interpreted broadly and included health (case rates, hospitalization, fatality, etc.) as well as mental health and psychosocial impacts. Articles that only described changes to the service system were not included. Additionally, gray literature, including dissertations, theses, conference proceedings, and articles that appeared in sources that were not peer reviewed, as were articles that did not have empirical findings, such as reviews or theoretical or conceptual papers. Finally, case studies of only one individual were excluded.

Data Analysis Approach

Data extraction and analysis followed guidelines for directed content analysis suggested by Hsieh and Shannon (2005). Directed content analysis is a deductive qualitative method intended to validate, describe, or extend an existing theory (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Since epistemic injustice has been well defined as a theory in prior literature but has not been applied to the health inequities of people with IDD, directed content analysis was deemed appropriate for this study since we were able to apply a well-defined theory in a novel way. Consistent with this analytical approach, codes were determined and defined a priori based on existing research on health equity for people with IDD and on Fricker’s (2007) core elements of epistemic injustice (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). These codes and definitions are presented in Table 1. Following guidelines suggested by Hsieh and Shannon (2005), we read each article and highlighted text that related to the impact of COVID-19 on people with IDD and/or reflected the influence of epistemic injustice. We then coded all highlighted passages using the previously defined codes (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

| Code | Definition |

|---|---|

| Manifest Codes: COVID-19 Impact | Hospitalization and Mortality: findings related to COVID-19 case rates, treatment, hospitalization, intensive care/intubation, death |

| Mental Health: findings related to official mental health diagnoses (depression, anxiety, bipolar, etc.) and reported symptoms of mental illness | |

| Psychosocial: findings related to disruption in daily lives of people with IDD | |

| Latent Codes: Epistemic Injustice | Testimonial Injustice: The injustice that a speaker suffers in receiving deflated credibility from the hearer owing to identity prejudice on the hearer’s part |

| Identity power: “a form of social power which is directly dependent upon shared social-imaginative conceptions of the social identities of those implicated in the particular operation of power” (Fricker, 2007, p. 4) | |

| Identity prejudice: “prejudices against people qua social type” (Fricker, 2007, p. 4) | |

| Testimonial sensibility: “a form of rational sensitivity that is socially inculcated and trained by countless experiences of testimonial exchange, individual and collective” (Fricker, 2007, p. 5) | |

| Testimonial justice: “a virtue such that the influence of identity prejudice on the hearer’s credibility judgment is detected and corrected for” (Fricker, 2007, p. 5) | |

| Epistemic objectification: “the subject is wrongfully excluded from the community of trusted informants, and this means he is unable to be a participant in the sharing of knowledge (except in so far as he might be made use of as an object of knowledge through others using him as a source of information). He is thus demoted from subject to object…” (Fricker, 2007, p. 6) | |

| Hermeneutical injustice: “a gap in our shared tools of social interpretation–where it is no accident that the cognitive disadvantage created by this gap impinges unequally on different social groups” (Fricker, 2007, p. 6) | |

| Hermeneutical marginalization: marginalized groups “participate unequally in the practices through which social meanings are generated; collective forms of understanding are rendered structurally prejudicial in respect of content and/or style: the social experiences of members of hermetically marginalized groups are left inadequately conceptualized and so ill-understood…” (Fricker, 2007, p. 6) | |

| Situated hermeneutical inequality: “social situation is such that a collective hermeneutical gap prevents them in particular from making sense of an experience which it is strongly in their interests to render intelligible” (Fricker, 2007, p. 7) | |

| Hermeneutical justice: “hearer exercises a reflexive critical sensitivity to any reduced intelligibility incurred by the speaker owing to a gap in collective hermeneutical resources.” (Fricker, 2007, p. 7) |

Researcher Positionality

Because the positionality of the researchers can have an impact on the research process and presentation of findings, the authors offer these statements to describe their own positionality as pertinent to this work.

The first author identifies as a White queer female. She has over 10 years of experience working with people with IDD in a variety of settings in the U.S. and abroad, including work on inclusive research methods.

The second author identifies as a White male with a chronic health condition that affects his daily living. Having grown up in a setting where he was surrounded by people with IDD, he considers himself a lifelong disability advocate. He has 20 years of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research experience.

Results

Included Articles

Searches of the three initial databases yielded 197 articles after excluding duplicates. Fifteen articles remained after screening the titles and abstracts for eligibility based on the above criteria. For example, our initial search returned articles based outside of the U.S., articles that did not explicitly focus on people with IDD, and case studies about individuals with specific diagnoses, all of which could be determined through a review of the title and/or abstract.

Five articles were excluded after a full-text review because they contained only case studies of individuals or service organizations (N = 3), did not focus on people with IDD (N = 1), or were a scoping review that did not provide enough detailed results for data analysis (N = 1). A hand search of reference lists yielded one additional article that met inclusion criteria. Finally, the Google Scholar “cited by” search yielded five articles. In total, 16 articles were retained for content analysis that were published between July 2020 and April 2022.

Of the 16 studies included in the final analysis, only one used qualitative methods to understand the experiences of people with IDD during the COVID-19 pandemic (Carey et al., 2021). Three studies utilized surveys of adults with IDD that allowed for proxy-responses to some or all questions (Fisher et al., 2022; Friedman, 2021; Rosencrans et al., 2021), and two studies only surveyed caregivers (family members and paid staff; Hartley et al., 2022; Linehan et al., 2022). The remaining 10 studies used secondary data analysis (Davis et al., 2021; Gleason et al., 2021; Karpur et al., 2021; Koyama et al., 2022; Landes et al., 2020, Landes, Turk, Damiani, et al., 2021; Landes, Turk, & Ervin, 2021; Landes, Turk, & Wong, 2021; Malle et al., 2021; Turk et al., 2020). Included articles are presented in Table 2.

| Reference | Research question/aim | Methods | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carey et al. (2021) | To capture and analyze adults’ lived experiences with ID during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Focus groups of graduates and currently enrolled post-secondary education students (N = 9) | Four themes (employment, daily living, social, well-being) and eleven subthemes emerged during the interviews. Participants described the impact of COVID-19, such as learning, and implementing new procedures in the workplace, taking on increased responsibilities at home, and the uncertainty of their future. |

| Davis et al. (2021) | To examine the impact of COVID-19 on the health of people with IDD at both early (May 2020) and later points (January 2021) in the pandemic to examine how early trends related to infection and fatality rates have changed over time. | Data on infection and mortality obtained from IDD organizations in California, Colorado, Indiana, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia and from Johns Hopkins from May 2020 and January 2021. | The infection rate in May 2021 was lower for adults with IDD than for the general population (.74). Fatality rates declined overall, but people with IDD remained twice as likely to die from COVID-19 (2.29) |

| Fisher et al. (2022) | To examine factors that predict stress level and life satisfaction among adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic and the role of social support. | Online survey of adults with and without disabilities (N = 2,028), 181 with IDD (or proxy). | 92.8% of respondents reported negative impact of the pandemic. Negative impact was related to stress level, social support reduced stress. Stress level and the negative impact of the pandemic were inversely related to life satisfaction; social support was positively related to life satisfaction. Social support partially mediated the association between stress level and life satisfaction. |

| Friedman (2021) | To explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality-of-life outcomes of PWIDD. | We conducted a secondary analysis of Personal Outcome Measures® interviews from 2019 to 2020 (n = 2,284). | There were significant differences in the following quality of life outcomes of PWIDD between 2019 and 2020: continuity and security; interact with other members of the community; participate in the life of the community; intimate relationships; and choose goals. |

| Gleason et al. (2021) | To understand the risk of contracting COVID-19, being admitted to the hospital, and being admitted to the ICU for people with IDD. | Cross sectional study of 547 health care providers (N = 467,773 patients) with COVID diagnosis from April 2020 to August 2020. | This study found that those with developmental disabilities were over 3 times as likely to die following a diagnosis of Covid-19 and that those with intellectual disabilities were 2.75 times as likely to die following such a diagnosis, |

| Hartley et al. (2022) | To understand how the COVID-19 pandemic has altered daily life (including residence, employment, and participation in adult disability day programs) and influenced the mood and behavior of adults with Down syndrome. | Online or telephone survey of caregivers of adults with DS (N = 171) in U.S. and UK. | The residence of 17% of individuals was altered, and 89% of those who had been employed stopped working during the pandemic. One-third (33%) of individuals were reported to be more irritable or easily angered, 52% were reported to be more anxious, and 41% were reported to be more sad/depressed/unhappy relative to pre-pandemic. |

| Karpur et al. (2021) | To illustrate the impact of COVID-19 infection on the health of individuals with ASD when compared to their peers with other chronic conditions. | Fair Health National Private Insurance Claims database Feb 1, 2020, through Sep 30, 2020 (N = 35,898,076). | Individuals with ASD + ID were nine times more likely to be hospitalized following COVID-19 infection and were nearly six times more likely to have an elevated length of hospital stay compared to those without ASD + ID. |

| Koyama et al. | To evaluate the association between intellectual and develop-mental disabilities (IDDs) and severe COVID-19 outcomes, 30-day readmission, and/or increased length of stay (LOS) using a large electronic administrative database. | Data from 900 hospitals from Premier Healthcare Database Special COVID-19 release. COVID-19 discharge data March 1, 2020, through June 30, 2021 (N = 643,765). | Patients with any IDD were at a significantly greater risk of at least 1 severe outcome, 30-day readmission, or longer LOS than patients without any IDD. Compared with those without any IDD, patients with Down syndrome had the greatest odds of ICU admission (odds ratio [OR] and 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.96 [1.73-2.21]), IMV (OR: 2.37 [2.07-2.70]), and mortality (OR: 2.33 [2.00-2.73]). Patients with ASD and those with Down syndrome both had over a 40% longer mean LOS. Patients with intellectual disabilities had a 23% (12-35%) increased odds of 30-day readmission. |

| Landes, Turk, Damiani, et al. (2021).

|

What individual and residential characteristics are associated with COVID-19 outcomes for people with intellectual and develop-mental disabilities receiving residential services? | Cohort study of 543 people with IDD receiving residential services in NY from March 1 to October 1, 2020. Data obtained through case files. | Age, larger residential settings, Down syndrome, and chronic kidney disease were associated with COVID-19 diagnosis. Heart disease was associated with COVID-19 mortality |

| Landes, Turk, & Ervin (2021). | This study compared COVID-19 case-fatality rates among people with IDD in 11 states and the District of Columbia that are publicly reporting data. | Publicly reported data on COVID-19 outcomes (cumu-lative cases and deaths) among people with IDD March 31 – April 13, 2021, from 12 jurisdictions, com-pared to Johns’ Hopkins data. | Comparison of case-fatality rates between people with IDD and their respective jurisdiction populations demonstrates that case-fatality rates were consistently higher for people with IDD living in congregate residential settings (fifteen instances) and receiving 24/7 nursing services (two instances). Results were mixed for people with IDD living in their own or a family home (eight instances). |

| Landes et al. (2020).

|

To describe COVID-19 outcomes among people with IDD living in residential groups homes in the state of New York and the general population of New York State. | Data from 115 service providers in NY from January to May 28, 2020, including case rates, fatality, and mortality. Data from NY state and city health departments. | People with IDD in residential settings had higher case rates, fatality rates, and mortality rates compared to the general population. |

| Landes, Turk, & Wong. (2021). | To determine the impact of residential setting and level of skilled nursing care on COVID-19 outcomes for people receiving IDD services, compared to those not receiving IDD services. | Data from California depart-ment of DDS compared with data from California Open Data Portal, as of May 2020. | Compared to Californians not receiving IDD services, in general, those receiving IDD services had a 60% lower case rate, but 2.8 times higher case-fatality rate. COVID-19 outcomes varied significantly among Californians receiving IDD services by type of residence and skilled nursing care needs: higher rates of diagnosis in settings with larger number of residents, higher case-fatality and mortality rates in settings that provided 24-h skilled nursing care. |

| Linehan et al. (2022) | What are family members’ and paid staff’s perceptions of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on individuals with IDD and their caregivers? Do differences exist in the self-reported experiences of those supporting individuals living in different living arrangements and in different international juris-dictions? | International online survey of family members, paid staff, and case managers (N = 3,754). | Caregivers observed increases in depression/ anxiety, stereotyped behaviors, aggression towards others and weight gain in the person(s) they supported. They also reported difficulties supporting the person(s) to access healthcare. Families reported reducing or ceasing employment and absorbed additional costs when supporting their family member. Direct support professionals experienced changes in staff shifts, staff absences, increased workload and hiring of casual staff. Caregivers’ wellbeing revealed high levels of stress, depression, and less so anxiety. |

| Malle et al. (2021) | To conduct an analysis of individuals with DS who were hospitalized with COVID-19 in New York, New York, USA. | Retrospective, dual-center study of 7246 patients hospitalized with COVID-19, we analyzed all patients with DS admitted in the Mount Sinai Health System and Columbia University Irving Medical Center. We assessed hospitalization rates, clinical characteristics, and outcomes. | Hospitalized individuals with DS are on average ten years younger than patients without DS. Patients with DS have more severe disease than controls, particularly an increased incidence of sepsis and mechanical ventilation |

| Rosencrans et al. (2021)

|

To explore mental health problems and services in individuals with IDD during the pandemic. We explored whether number of mental health problems differed by disability, age, gender, living situation, physical health, and access to services. | Online survey of adults with IDD and caregivers in U.S. and Chile. U.S. N = 404 (75% with helper); completed July 2020. | US sample reported difficulty accessing/changes in services. 9% increased health problems, 15% difficulty accessing healthcare, 29% feeling scared to go to the doctor. 41% reported more mental health problems since COVID began |

| Turk et al. (2020) | To compare COVID-19 trends among people with and without IDD, overall and stratified by age. | TriNetX COVID-19 database: electronic medical records from 42 health care organizations. Data from all patients with COVID-19 diagnosis through May 14, 2020 (N = 30,282). | People with IDD had a higher prevalence of specific comorbidities associated with poorer COVID-19 outcomes. Distinct age-related differences in COVID-19 trends were present among those with IDD, with a higher concentration of COVID-19 cases at younger ages. In addition, while the overall case-fatality rate was similar for those with IDD (5.1%) and without IDD (5.4%), these rates differed by age: ages ≤ 17 – IDD 1.6%, without IDD < 0.01%; ages 18–74 – IDD 4.5%, without IDD 2.7%; ages ≥ 75– IDD 21.1%, without IDD, 20.7%. |

Outcomes

Results are presented in two sections. The first section presents manifest findings, which describe the impact of COVID-19 on physical health, mental health, and psychosocial factors for people with IDD that are directly stated in the articles included in the review. This section largely corresponds to our first research question. The second section presents latent findings, which are examples of epistemic injustice that may not be directly stated but can be inferred from the more explicit findings.

Manifest Findings

COVID-19 Related Hospitalization and Mortality

Poor physical health outcomes for people with IDD were documented in 10 of the articles identified in the scoping review (Davis et al., 2021; Gleason et al., 2021; Karpur et al., 2021; Koyoma et al., 2022; Landes et al., 2020 Landes, Turk, Damiani, et al., 2021; Landes, Turk, & Ervin, 2021; Landes, Turk, & Wong, 2021; Malles et al., 2021; Turk et al., 2020). Of the studies that examined physical health outcomes, four studies reported that people with IDD were more likely to be hospitalized, have longer hospital stays, and/or be admitted to the ICU compared to patients without IDD (Gleason et al., 2021; Karpur et al., 2021; Koyoma et al., 2022; Malles et al., 2021). Additionally, seven studies reported a higher mortality or case-fatality rate from COVID-19 for patients with IDD (Davis et al., 2021; Gleason et al., 2021; Koyoma et al., 2022; Landes et al., 2020, Landes, Turk, & Ervin, 2021); Landes, Turk, & Wong, 2021; Malles et al., 2021). One study (Turk et al., 2020) found that the overall case fatality rate was similar between patients with and without IDD, but that people with IDD who died from COVID-19 tended to be younger than people without IDD.

Mental Health and Psychosocial Outcomes

Six of the included studies reported on mental health and/or psychosocial outcomes for people with IDD during the COVID-19 pandemic (Carey et al., 2021; Fisher et al., 2022; Friedman, 2021; Hartley et al., 2022; Linehan et al., 2022; Rosencrans et al., 2021). Overall, these articles reported negative outcomes from the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies suggest that participants were more worried, stressed, or anxious during COVID-19 than before the pandemic (Carey et al., 2021; Fisher et al., 2022; Hartley et al., 2022; Linehan et al., 2022; Rosencrans et al., 2022). Studies also reported high rates of changes in the daily lives of people with IDD because of COVID-19 and the public health response, including changes to employment or day programs (Carey et al., 2021; Fisher et al., 2022; Hartley et al., 2022), social activities (Carey et al., 2021; Friedman, 2021), residence, support staff, and disability services (Hartley et al., 20220; Linehan et al., 2022), and access to healthcare (Linehan et al., 2022; Rosencrans et al., 2021).

Latent Findings

Unsurprisingly, none of the articles explicitly referenced epistemic injustice in their analyses of the impacts of COVID-19 on people with IDD. However, instances of testimonial and/or hermeneutical injustice can be applied to findings in this scoping review.

Testimonial Injustice

Testimonial injustice is most seen in an examination of the research methods in this scoping review of the literature. As described previously, only one study used qualitative methods with participants with IDD (Carey et al., 2021), while 10 studies used secondary data analysis (Davis et al., 2021; Gleason et al., 2021; Karpur et al., 2021; Koyama et al., 2022; Landes et al., 2020; Landes, Turk, Damiani, et al., 2021; Landes, Turk, & Ervin, 2021; Landes, Turk, & Wong, 2021; Malle et al., 2021; Turk et al., 2020). Secondary data analysis is a key tool for public health research, but the preponderance of secondary data at the exclusion of studies actively involving people with IDD suggests the possibility of epistemic objectification in research about COVID-19 and people with IDD (Fricker, 2007). In epistemic objectification, a person or group is treated as a “mere object” rather than an active participant in knowledge creation, amounting “to a sort of dehumanization” (Fricker, 2007; p. 133).

Fricker (2007) is also clear that exclusion does not have to be explicit to constitute testimonial injustice. Instead, people from marginalized social groups “tend simply not to be asked to share their thoughts” on issues that concern them (Fricker, 2007, p. 130). In this review, two articles (Hartley et al., 2022; Linehan et al., 2022) only surveyed caregivers of people with IDD, rather than soliciting opinions directly. This finding is particularly noteworthy as both articles reported subjective impacts of COVID-19, including increased feelings of anxiety, although people with IDD were not given the opportunity to share those feelings firsthand.

Additionally, we identified several clear examples of testimonial justice in the identified research methods. Carey et al. (2021) and Rosencrans et al. (2021) stated that materials were written in plain language and checked for accessibility prior to beginning the study. Rosencrans et al. also described the process by which proxy responses were allowed, specifying that questions were designed to be read aloud by a “helper” who supported the respondent with IDD.

Carey et al (2021) demonstrates one way in which people with IDD can be centered in the research process. Researchers in this study developed focus group questions based on previous literature on health inequities and COVID-19, ensuring that questions were written in a way that participants would easily understand (Carey et al., 2021). An expert panel reviewed these questions for reading level and for comprehensiveness, leading researchers to add an additional category of questions (Carey et al., 2021). Focus groups were then held over Zoom, with researchers present to troubleshoot any technological issues that impeded full participation (Carey et al., 2022).

Hermeneutical Injustice

Several examples of hermeneutical injustice can also be seen in this review. Multiple authors describe a situated hermeneutical inequality wherein a gap in collective knowledge disproportionately impacts a particular group by hampering research and interventions (Fricker, 2007). In the context of COVID-19, a lack of robust data about the impacts of the virus or general health outcomes for people with IDD may have contributed to inequitable public health responses (Friedman, 2021; Landes et al., 2020; Landes, Turk, & Wong, 2021; Turk et al., 2020). Specifically, Friedman (2021), Landes et al. (2020), Landes, Turk, & Wong (2021), and Turk et al. (2020) all described inadequate surveillance of COVID-19 in people with IDD, particularly for people who lived in congregate settings. Gleason et al. (2021) and Karpur et al. (2021) used electronic health records in their research and reported that inaccurate or missing diagnostic codes limited their research. Finally, Linehan et al. (2022) described how people with IDD are often excluded from large, population-based health surveys, contributing to the poor understanding of health outcomes for this population.

Landes, Turk & Ervin (2021) suggest that the lack of robust information about health outcomes for people with IDD before and during the COVID-19 pandemic limited the public health response for this population. For example, while many states prioritized people with IDD who lived in congregate settings in their vaccine rollout, many did not include people with IDD who lived in non-congregate settings (Landes, Turk, & Ervin, 2021). The authors propose that this exclusion may have been due in part to a lack of data about the impact of COVID-19 on people with IDD who live in the community (Landes, Turk, & Ervin, 2021). The situated hermeneutical inequality, wherein very little robust public health data exists for people with IDD, contributed to an exacerbation of existing inequities, further marginalizing this population.

Authors also suggest that people with IDD may have been excluded from the public health response to COVID-19 because of hermeneutical marginalization, where the interpretation of a particular issue is based on the experiences of more hermeneutically powerful groups, rather than the group most directly impacted (Fricker, 2007). For example, Landes and colleagues (2020) argue that the public health officials who determined COVID-19 policies did so without a robust understanding about group homes for people with IDD. This example clearly highlights how the hermeneutical marginalization of a group can directly translate to policy decisions that exacerbate inequities–public health officials do not understand how group homes work and so implement policies that put people with IDD at increased risk (Landes et al., 2020).

Discussion

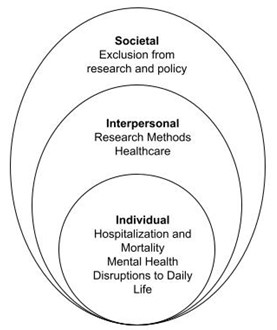

This scoping review of the literature supports the claim that people with IDD faced significant difficulties during the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic and highlights the ways in which epistemic injustice, as described by Fricker (2007), may be shaping research and the ways that people with IDD are considered in the COVID-19 pandemic response in the U.S. The relationships between the manifest and latent findings of this review are presented in Figure 1.

This model draws from the social ecological model proposed by Bronfenbrenner (1977) and centers individual-level manifest findings in the innermost of a series of nested circles. Testimonial injustice is situated in the next circle, indicating the ways in which interpersonal interactions in data collection or in healthcare settings may influence these outcomes. Finally, hermeneutical injustice is depicted in the outermost circle, representing how the systemic exclusion of people with IDD from research and policy impacts both interpersonal relationships and individual-level outcomes.

Individual Level: Manifest Findings

Literature suggests a range of poor physical health outcomes associated with COVID-19 for people with IDD, including higher rates of infection, hospitalization, and death compared to people without IDD (Davis et al., 2021; Gleason et al., 2021; Karpur et al., 2021; Koyoma et al., 2022; Landes et al., 2020; Landes, Turk, Damiani, et al., 2021; Landes, Turk, & Ervin, 2021; Landes, Turk, & Wong, 2021; Malles et al., 2021; Turk et al., 2020). Additionally, people with IDD faced disruptions to services, employment, and community integration due to COVID-19 and the public health response (Carey et al., 2021; Fisher et al., 2022; Friedman, 2021; Hartley et al., 2022; Linehan et al., 2022; Rosencrans et al., 2021). Several studies suggested that people with IDD have higher rates of anxiety, stress, and depression (Carey et al., 2021; Fisher et al., 2022; Hartley et al., 2022; Linehan et al., 2022; Rosencrans et al., 2022) than they did before the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings make claims that people with IDD were excluded from the COVID-19 response in the U.S. particularly concerning and highlight the implications of epistemic injustice, as discussed in the following sections (CPR, 2020; Hotez, 2021; Jain et al., 2021; Landes et al., 2020; Wiggins et al., 2021).

Interpersonal Level: Testimonial Injustice

Testimonial injustice is clearly seen in the reliance on secondary data and proxy reporters in the studies identified in this review, which suggests that epistemic injustice may be built into prevailing research methods for learning about people with IDD. As stated previously, negative stereotypes about people or groups do not need to be believed by researchers to influence the ways they conduct research (Fricker, 2007). The studies identified in this review highlight the ongoing challenges in conducting research with people with IDD; only one study explicitly centered on the lived experiences of people with IDD (Carey et al., 2021).

Some projects that include people with IDD as participants or co-researchers are not approved by university ethics committees because of assumptions about capacity and disability (Stack & McDonald, 2014). Once projects are approved, creating accessible research materials is time consuming and costly (Stack & McDonald, 2014), particularly for participants who do not read or communicate verbally (Scott & Havercamp, 2018). Taken as a whole, this combination of practical challenges and negative stereotypes about people with IDD seems to have limited opportunities for research with this population. A random survey of clinical trials found that only 2% of studies included participants with intellectual disabilities (Feldman et al., 2014).

Carey et al. (2021) offers both practical guidance for promoting testimonial injustice in research with people with IDD and demonstrate the benefits of doing so. In developing questions for their focus groups, researchers integrated both existing literature and the perspectives of experts in the field to ensure that questions were easily understood and captured the full range of experiences (Carey et al., 2021). Additionally, researchers met with participants to explain the study verbally prior to the focus groups and were on hand to provide practical support during the focus groups to support full participation (Carey et al., 2021). In intentionally balancing established academic knowledge with the lived experiences of research participants, Carey et al. captured nuanced details about the impact of COVID-19 on the lives of people with IDD. The researchers note that all participants in their study had previously participated in training on self-advocacy and the use of technology, suggesting that including people with IDD in the research process may be a long-term project.

Beyond research, testimonial injustice in interactions between healthcare providers and patients with IDD may be related to the high rates of hospitalization and death reported in this review. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, research suggested that testimonial injustice based on negative social constructions can lead medical providers to rate patients with disabilities as having a lower quality of life than patients without disabilities (Albrecht & Devlieger, 1999; Iezzoni et al., 2021; Peña-Guzmán & Reynolds, 2019). This example of testimonial injustice reinforces the existing power structure wherein healthcare providers are believed and patients with disabilities are denied the opportunity to act as experts in their own lives and experiences (Albrecht & Devlieger, 1999; Iezzoni et al., 2021; Peña-Guzmán & Reynolds, 2019) and is particularly impactful in the context of understanding impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with IDD. While the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights (OCR) explicitly forbade treatment rationing protocols based on subjective measures of quality of life, research from before the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that healthcare providers might not be aware of their own biases in decision making (Peña-Guzmán & Reynolds, 2019).

Societal Level: Hermeneutical Injustice

While testimonial justice denies patients with IDD agency in healthcare settings, hermeneutical injustice, or an exclusion from the process of knowledge creation for members of less powerful groups, perpetuates this exclusion on a broader scale. Research on health outcomes for people with IDD is limited by a lack of data (Havercamp et al., 2019; Krahn, 2019). This lack of data was noted by researchers prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Havercamp et al., 2019; Krahn et al., 2019). Many population-level surveys make it impossible to identify people with IDD because they lack disability identifiers, use broad language that does not distinguish between conditions like intellectual disability, developmental disability, dementia, and traumatic brain injury, or do not include people with IDD in their sampling frames (Havercamp et al., 2019; Krahn, 2019). One study suggested that national health surveillance surveys only identify about 60% of adults with IDD who live in the community (Magana et al., 2016).

Again, these existing injustices were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several studies noted that their own research was limited by a lack of robust data about health outcomes for people with IDD prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic (Friedman, 2021; Gleason et al., 2021; Karpur et al., 2021; Landes et al., 2020, Landes, Turk, & Wong, 2021; Turk et al., 2020). This exclusion from existing population-level research may have contributed to people with IDD being largely left out of the COVID-19 response in the U.S. (Hotez et al., 2021). When knowledge is unavailable, it cannot be used in data-driven decision making, leading to exclusion and marginalization. As the subjects of study are often determined by epistemically and socially privileged groups, these exclusions can perpetuate and exacerbate existing inequalities.

Implications

This scoping review of the literature on the impacts of COVID-19 on people with IDD supports Fricker’s (2007) claim that epistemic injustice is both a moral and an intellectual virtue, serving “equally both justice and truth” (p. 121). Achieving epistemic justice and, in the context of the COVID-19, equitable health outcomes, requires those with power to critically challenge the prejudices and stereotypes they hold against less powerful groups and the ways that these beliefs have shaped policy and practice. As the U.S. moves into the endemic phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, confronting the underlying injustices in the response so far has important implications for research, practice, and policy.

The first step to confronting epistemic injustice is to make people aware of its existence and its impacts (Fricker, 2007). When people are silenced–in the doctor’s office or in the data–the status quo continues unchallenged (Fricker, 2007). Developing robust and inclusive research methods that capture the needs and experiences of people with IDD is essential to promoting health equity. Researchers have suggested several practices to improve research for and with people with IDD including using merged datasets, high quality psychometrics, and advanced statistical analyses (Bogenschutz et al., 2022).

Beyond the lack of information, research about health outcomes for people with IDD does exist rarely centers the experiences and needs of people with IDD and their families (Hotez et al., 2021). Truly inclusive and epistemically just research involves people with IDD at all stages of the research process, as active agents in the creation and dissemination of knowledge (Fricker, 2007; Strnadová & Walmsley, 2018; Walmsley & Johnson, 2003). As noted previously, our review found only one qualitative article that centered on the experiences of people with IDD (Carey et al., 2021). Expanding inclusive qualitative research methods to elucidate the voices and perspectives of people with disabilities, in concert with more robust data, would greatly benefit the field.

Expanding the data about the experiences and health outcomes of people with IDD, particularly in the context of a global health emergency like the COVID-19 pandemic, serves to address both the intellectual and moral failings described by Fricker (2007). It addresses the pervasive testimonial injustice faced by people with IDD by explicitly soliciting their own opinions and experience, especially using inclusive and qualitative research methods. Quantitative methods and secondary data analysis that include disability identifiers and include people with IDD in their sampling frames can move towards hermeneutical justice by expanding the available knowledge about people with IDD that can be used in making policy and other decisions. Together, these changes can help to contribute to more ethical and equitable healthcare and policy for people with IDD.

Limitations

As with any study, this review has several limitations that should be noted. The literature review took place at one point in time (April 2022) during a rapidly evolving global pandemic and public health response. While the spring of 2022 was a relatively stable moment in the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S., when all but the youngest children were eligible for the vaccine and between surges from Omicron variants, any information must be taken in the context of a constantly evolving situation. Statements that were true in 2020, when COVID-19 was first identified, may not hold over time.

Furthermore, the lack of a coordinated federal response to COVID-19 limited state responses to the virus and the generalizability of this review. Of the studies that used secondary data to examine the health impacts of COVID-19 on people with IDD, six used data from specific geographic regions (Davis et al., 2021; Landes et al., 2020; Landes, Turk, Damiani, et al., 2021; Landes, Turk, & Ervin, 2021; Landes, Turk, & Wong, 2021; Malle et al., 2021). Given the wide variation in the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. and in different states’ responses to the virus, findings from these studies may not be generalizable to the U.S.

Conclusion

Considering the needs of people with IDD, other disabilities, and chronic health conditions remains important as the U.S. exits the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and relaxes public health measures. Applying the framework of epistemic justice, addressing these inequitable policies means continuing to amplify the voices of people with disabilities.

References

Abbas, J. (2016). Economy, exploitation, and intellectual disability. In R. Malhotra (Ed.), Disability politics in a global economy (pp. 151-163). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315714011

Albrecht, G. L., & Devlieger, P. J. (1999). The disability paradox: High quality of life against all odds. Social Science & Medicine, 48(8), 977-988. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00411-0

Bhakuni, H., & Abimbola, S. (2021). Epistemic injustice in academic global health. The Lancet Global Health, 9(10), e1465-e1470. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00301-6

Bogenschutz, M., Dinora, P., Lineberry, S., Prohn, S., Broda, M., & West, A. (2022). Promising practices in the frontiers of quality outcome measurement for intellectual and developmental disability services. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 3. http://doi.org/https://doi-org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.3389%2Ffresc.2022.871178

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Carel, H., & Kidd, I. J. (2014). Epistemic injustice in healthcare: A philosophical analysis. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 17(4), 529-540. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-014-9560-2

Carey, G. C., Joseph, B., & Finnegan, L. A. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on college students with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation(Preprint), 1-11. http://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-211162

Catala, A. (2020). Metaepistemic injustice and intellectual disability: A pluralist account of epistemic agency. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 23(5), 755-776. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-020-10120-0

Center for Public Representation (CPR). (2020). COVID-19 medical rationing. https://www.centerforpublicrep.org/ covid-19-medical-rationing/

Davis, M. D., Spreat, S., Cox, R., Holder, M., Burke, K. M., & Martin, D. M. (2021). COVID-19 mortality rates for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. International Journal of Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences Archive. https://doi.org/10.53771/ijbpsa.2021.2.1.0075

Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 2000, 42 US.C.A. 1500

FAIR Health, West Health Institute, & Makary, M. (2020). Risk factors for COVID-19 mortality among privately insured patients: A claims data analysis. FAIR Health. https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/ asset/Risk%20Factors%20for%20COVID-19%20Mortality%20among%20Privately%20Insured%20Patients%20-% 20A%20Claims%20Data%20Analysis%20-%20A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf

Feldman, M. A., Bosett, J., Collet, C., & Burnham‐Riosa, P. (2014). Where are persons with intellectual disabilities in medical research? A survey of published clinical trials. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(9), 800-809. http://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12091

Fisher, M. H., Sung, C., Kammes, R. R., Okyere, C., & Park, J. (2022). Social support as a mediator of stress and life satisfaction for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 35(1), 243-251. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12943

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press.

Fricker, M. (2017). Evolving concepts of epistemic injustice. In I. J. Kidd, J. Medina, & G. Pohlhaus Jr. (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of epistemic injustice (pp. 53-60). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315212043

Friedman, C. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and quality of life outcomes of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 14(4), 101117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo. 2021.101117

Gleason, J., Ross, W., Fossi, A., Blonksy, H., Tobias, J., & Stephens, M. (2021). The devastating impact of COVID-19 on individuals with intellectual disabilities in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) Catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.21.0051

Goodey, C. F. (2001). What is developmental disability? The origin and nature of our conceptual models. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 8(2), 1-18.

Guevara, A. (2021). The need to reimagine disability rights law because the medical model of disability fails us all. Wisconsin Law Review, 2021(2), 269-292.

Hartley, S. L., Fleming, V., Piro-Gambetti, B., Cohen, A., Ances, B. M., Yassa, M. A., Brickman, A. M., Handen, B. L., Head, E., Mapstone, M., Christian, B. T., Lott, I. T., Doran, E., Zaman, S., Krinsky-McHale, S., Schmitt, F. A., Hom, C., Schupf, N., & ABC-DS Group. (2022). Impact of the COVID 19 pandemic on daily life, mood, and behavior of adults with Down syndrome. Disability and Health Journal, 15(3). 101278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2022.101278

Havercamp, S. M., Krahn, G. L., Larson, S. A., Fujiura, G., Goode, T. D., Kornblau, B. L., & National Health Surveillance for IDD Workgroup. (2019). Identifying people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in national population surveys. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 57(5), 376-389. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-57.5.376

Hotez, E., Hotez, P. J., Rosenau, K. A., & Kuo, A. A. (2021). Prioritizing COVID-19 vaccinations for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. EClinicalMedicine, 32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100749

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Iezzoni, L. I., Rao, S. R., Ressalam, J., Bolcic-Jankovic, D., Agaronnik, N. D., Donelan, K., Lagu, T., & Campbell, E. G. (2021). Physicians’ perceptions of people with disability and their health care: Study reports the results of a survey of physicians’ perceptions of people with disability. Health Affairs, 40(2), 297-306. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01452

Jain, V., Schwarz, L., & Lorgelly, P. (2021). A rapid review of COVID-19 vaccine prioritization in the US: alignment between federal guidance and state practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073483

Kalman, H., Lovgren, V., & Sauer, L. (2016). Epistemic injustice and conditioned experience: The case of intellectual disability. Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s & Gender Studies, 15(1), 4. https://digitalcommons.cortland.edu/wagadu/vol15/iss1/4utm_source=digitalcommons.cortland.edu%2Fwagadu%2Fvol15%2Fiss1%2F4&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages

Karpur, A., Vasudevan, V., Shih, A., & Frazier, T. (2021). Brief report: Impact of COVID-19 in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: Analysis of a National Private Claims Insurance database. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52, 2350-2356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05100-x

Koyama, A. K., Koumans, E. H., Sircar, K., Lavery, A., Hsu, J., Ryerson, A. B., & Siegel, D. A. (2022). Severe outcomes, readmission, and length of stay among COVID-19 patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 116, 328-330. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.01.038

Krahn, G. L. (2019). A call for better data on prevalence and health surveillance of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 57(5), 357-375. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-57.5.357

Krahn, G. L., Hammond, L., & Turner, A. (2006). A cascade of disparities: Health and health care access for people with intellectual disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 12(1), 70-82. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.20098

Landes, S. D., Turk, M. A., Damiani, M. R., Proctor, P., & Baier, S. (2021). Risk factors associated with COVID-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities receiving residential services. JAMA network open, 4(6), e2112862-e2112862. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12862

Landes, S. D., Turk, M. A., & Ervin, D. A. (2021). COVID-19 case-fatality disparities among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Evidence from 12 US jurisdictions. Disability and Health Journal, 14(4), 101116. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101116

Landes, S. D., Turk, M. A., Formica, M. K., & McDonald, K. E. (2020). COVID-19 trends among adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) living in residential group homes in New York state through July 10, 2020. Syracuse, NY: Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion, Syracuse University. https://surface.syr.edu/lerner/13/

Landes, S. D., Turk, M. A., & Wong, A. W. (2021). COVID-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disability in California: The importance of type of residence and skilled nursing care needs. Disability and Health Journal, 14(2), 101051. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101051

Larson, S. A., Eschenbacher, H. J., Taylor, B., Pettingell, S., Sowers, M., & Bourne, M. L. (2020). In-home and residential long-term supports and services for persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities: Status and trends through 2017. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Research and Training Center on Community Living, Institute on Community Integration. https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/203355/ Report_2012_InHome_and_Residential.pdf?sequence=1

Linehan, C., Birkbeck, G., Araten-Bergman, T., Baumbusch, J., Beadle-Brown, J., Bigby, C., Bradley, V., Brown, M., Bredewold, F., Chirwa, M., Cui, J., Godoy Gimenez, M., Gomeiro, T, Kanova, S., Kroll, T., Li, H., MacLachlan, M., Narayan, J., Nearchou, F.,… Tossebro, J. (2022). COVID-19 IDD: Findings from a global survey exploring family members’ and paid staff’s perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 on individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and their caregivers. HRB Open Research, 5, 27. https://doi.org/10.12688%2Fhrbopenres.13497.1

Magana, S., Parish, S., Morales, M. A., Li, H., & Fujiura, G. (2016). Racial and ethnic health disparities among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 4(3), 161–172. http://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-54.3.161

Malle, L., Gao, C., Hur, C., Truong, H. Q., Bouvier, N. M., Percha, B., Kong, X., & Bogunovic, D. (2021). Individuals with Down syndrome hospitalized with COVID-19 have more severe disease. Genetics in Medicine, 23(3), 576-580. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-020-01004-w

Pelleboer‐Gunnink, H. A., Van Oorsouw, W. M. W. J., Van Weeghel, J., & Embregts, P. J. C. M. (2017). Mainstream health professionals’ stigmatising attitudes towards people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 61(5), 411-434. http://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12353

Peña-Guzmán, D. M., & Reynolds, J. M. (2019). The harm of ableism: Medical error and epistemic injustice. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 29(3), 205-242. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/736764

Peters, M. D., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI evidence synthesis, 18(10), 2119-2126. http://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

Rosencrans, M., Arango, P., Sabat, C., Buck, A., Brown, C., Tenorio, M., & Witwer, A. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health, wellbeing, and access to services of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 114, 103985. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103985

Schalock, R. L., Luckasson, R., & Tassé, M. J. (2019). The contemporary view of intellectual and developmental disabilities: Implications for psychologists. Psicothema, 31 (3), 223-228. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2019.119

Scott, H. M., & Havercamp, S. M. (2018). Comparisons of self and proxy report on health‐related factors in people with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(5), 927-936. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.1111/jar.12452

Scully, J. L. (2018). From “she would say that, wouldn’t she?” to “does she take sugar?” Epistemic injustice and disability. IJFAB: International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 11(1), 106-124. https://www. jstor.org/stable/10.2307/90019579

Siebers, T. (2008). Disability theory. The University of Michigan Press.

Spreat, S., Cox, R., & Davis, M. (n.d.). COVID-19 case and mortality report: Intellectual or developmental disabilities. https://www.ancor.org/sites/default/files/covid-19_case_and_mortality_report.pdf

Stack, E., & McDonald, K. E. (2014). Nothing about us without us: does action research in developmental disabilities research measure up? Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11(2), 83-91. http://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12074

Strnadová, I., & Walmsley, J. (2018). Peer‐reviewed articles on inclusive research: Do co‐researchers with intellectual disabilities have a voice? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(1), 132-141. http://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12378

Trent, J. (2016). Inventing the feeble mind: A history of intellectual disability in the United States. Oxford University Press.

Turk, M. A., Landes, S. D., Formica, M. K., & Goss, K. D. (2020). Intellectual and developmental disability and COVID-19 case-fatality trends: TriNetX analysis. Disability and Health Journal, 13(3), 100942. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100942

Walmsley, J., & Johnson, K., (2003). Inclusive research with people with learning disabilities: Past, present and futures. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Wehmeyer, M. L., & Schalock, R. L. (2013). The parent movement: Late modern times (1950 CE to 1980 CE). In M. L Wehmeyer (Ed), The story of intellectual disability: An evolution of meaning, understanding, & public perception (pp. 187-231). Paul H. Brooks.

While, A. E., & Clark, L. L. (2010). Overcoming ignorance and stigma relating to intellectual disability in healthcare: A potential solution. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(2), 166-172. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01039.x

Wiggins, L. D., Jett, H., & Meunier, J. (2021). Ensuring equitable COVID-19 vaccination for people with disabilities and their caregivers. Public Health Reports, 137(2). http://doi.org/10.1177%2F00333549211058733

Wilkinson, J., Dreyfus, D., Cerreto, M., & Bokhour, B. (2012). “Sometimes I feel overwhelmed”: Educational needs of family physicians caring for people with intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(3), 243-250. http://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-50.3.243

Young, J. A., Lind, C., Orange, J. B., & Savundranayagam, M. Y. (2019). Expanding current understandings of epistemic injustice and dementia: Learning from stigma theory. Journal of Aging Studies, 48, 76-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2019.01.003