Conducting a Pilot Evaluation of a Civic-Engagement Program for Youth with Disabilities

Megan Best; Amanda Johnson; Sarah Demissie; Julianna Kim; Ruchi Khanna; Kelly Fulton; Abby Hardy; Catherine Cheung; Timothy Kunzier; Oscar Hughes; Meghan M. Burke; and Zachary Rosetti

Best, M., Johnston, A., Demissie, S., Kim, J., Mendiratta Khanna, R., Fulton, K., Hardy, A., Cheung, C., Kunzier, T., Hughes, O., Burke, M. M., & Rossetti, Z. (2024). Conducting a pilot evaluation of a civic-engagement program for youth with disabilities. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 4(2), 26-50. https://doi.org/10.59620/2694-1104.1086

Conducting a Pilot Evaluation of a Civic-Engagement Program for Youth with Disabilities PDF File

Plain Language Summary

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) ensures equal education for all students with disabilities. Last approved in 2004, only a small number of individuals with disabilities gave feedback on this law. To increase feedback next time, providing education on the law is critical. This study explored a 6-hour training program for young adults with disabilities. The program, developed and implemented with Parent Training Information Centers (PTIs) and co-researchers with disabilities, focused on IDEA and self-advocacy. PTIs aid parents in supporting students with disabilities in schools. Participants felt more prepared to influence the law. They proposed ideas to enhance disability laws. Both the young adults and PTIs found the program beneficial. Future research and actions are discussed.

Abstract

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is the federal law that ensures all students with disabilities have access to a free and appropriate public education. In the last IDEA reauthorization in 2004, only 1% of public comments were from individuals with disabilities—the population that IDEA serves. To ensure that the feedback of individuals with disabilities is reflected in the next IDEA reauthorization, it is important to support them to learn about IDEA and advocate. To this end, for this pilot study, 16 transition-aged youth with disabilities participated in a 6-hour civic-engagement program across four states to learn about IDEA and self-advocacy. The civic-engagement program was developed and conducted in collaboration with Parent Training and Information Centers (PTIs) and co-researchers with disabilities. After attending the program, participants demonstrated significant improvements in empowerment. Participants also suggested several ways to improve disability policy, including IDEA. Individuals with disabilities and PTIs reported that the civic-engagement program was feasible. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Introduction

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, the federal special education law) was last reauthorized in 2004. Given that IDEA has not been reauthorized for more than 20 years, IDEA is long-overdue for reauthorization. During an IDEA reauthorization, the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) strives to include stakeholders in the legislative process (Gartin & Murdick, 2005). In alignment with the rallying cry of the disability community “Nothing about us, without us,” it is critical to include individuals with disabilities in a reauthorization of IDEA. However, in the last IDEA reauthorization, out of the written and in-person testimonies, less than 1% (n = 3) were from individuals with disabilities (York, 2005). To increase the involvement of individuals with disabilities in the next IDEA reauthorization, the research team developed a 6-hour civic-engagement program. In this pilot study, the research team explored the development, preliminary effectiveness, feasibility, and social validity of the civic-engagement program among youth with disabilities.

It is critical for individuals with disabilities to co-design programs for other individuals with disabilities. Input from end users is often not considered when designing a program (National Institute of Mental Health, 2009). Indeed, most interventions are developed in controlled trials, rather than the deployment setting (i.e., the real- world setting; Mohr et al., 2017). Thus, the need to design a civic-engagement program alongside the end users (i.e., individuals with disabilities) not only aligns with the values of the self-advocacy movement but also with extant research. When co-researchers with disabilities are active team members on a research team, they can integrate their lived experiences, support the development of data collection, and provide rich interpretation to the data (Bigby et al. 2014). When individuals with disabilities, specifically those with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are fully involved in all phases of research, it ensures accessibility, inclusion, and social relevance (Hughes et al., 2020; Nicolaidis et al., 2019). Unfortunately, individuals with disabilities are often excluded in the research process or the development of interventions (Chown et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2022).

It is important to discern whether a civic-engagement program can benefit individuals with disabilities. Consider self-determination—the ability to cause things to happen in one’s life (Shogren et al., 2017). Self-determined action is defined by three essential characteristics including volitational action, agentic action, and action-control beliefs (Wehmeyer & Shogren, 2016). Self-determination involves an individual making decisions to set goals, acting to solve problems when working toward goals, and believing they can make changes and be supported in their life (Shogren et al., 2017). A civic-engagement program may increase self-determination by enabling individuals with disabilities to make their preferences and needs heard to legislators. A civic-engagement program may also increase empowerment among individuals with disabilities. To act (e.g., civic engagement) about an issue, it is necessary to feel empowered (i.e., to believe in one’s ability to control the situation; Gutierrez, 1990). Further, knowledge seems critical to civic engagement. Most parents of individuals with disabilities report that the primary barrier to civic engagement is lack of special education knowledge (Burke et al., 2018). If generalizable to individuals with disabilities, it seems that a civic-engagement program would also need to increase knowledge among its participants.

Given their lived experiences, youth with disabilities may have important feedback for the IDEA reauthorization. However, prior research has shown that youth with disabilities were less likely to engage in civic-engagement activities in young adulthood including volunteering and voting (Rim & Kim, 2023). There are few opportunities for youth with disabilities to participate in civic-engagement activities and voice their concerns (e.g., posting on social media platforms, Williamson et al., 2019). Consider the context of transition planning. Using the National Longitudinal Study (NLTS-2), Johnson et al. (2022) found that youth with disabilities were given few opportunities to participate in the development of their transition plans. While youth attendance at Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) has increased, youth with disabilities, especially those with IDD, continue to have little opportunity to take a leadership role or hold autonomy in the transition planning process (Chandroo et al., 2020; Kucharczyk et al., 2022; Shogren & Plotner, 2012). When considering civic engagement for adults with disabilities, many cite barriers such as a lack of accessible voting sites, requirements for voter identification, and a lack of plain language and accessible materials (Mann, 2018; Seekins et al., 2012). While little data have examined youth involvement in legislative advocacy, it seems that, based on the last IDEA reauthorization (York, 2005), youth with disabilities may also have limited opportunities to voice their feedback about special education and may experience barriers to be civically engaged adults. Because of their experiences, it is important to hear from youth with disabilities about needed changes to special education.

In combination with being effective, a civic-engagement program must also be feasible and socially valid. Put simply, a feasible program encompasses an individual’s desire to attend a program and there should be minimal attrition (Goddard & Harding, 2003). Without being feasible, a program cannot be effective, replicated, or sustained. Programs must also be socially valid. In a scoping review of studies about social validity, Snodgrass et al. (2022) found that, while the definition of social validity can vary, it was agreed that social validity differs from pure behavior change and the primary intervention effect. To this end, social validity may include gathering information from multiple sources to have a more holistic understanding of the importance of a program (Spear et al., 2013). Further, the sustainability of a program may also comprise its social validity. To facilitate sustainability, a program must be tested in multiple contexts and considered worthwhile by various implementers (Valdez et al., 2013). Thus, in the context of a civic-engagement program, it may be helpful to have the perspectives of individuals with disabilities as well as the individuals who facilitate the civic-engagement program to discern social validity.

Throughout history, individuals with disabilities have spearheaded many laws including the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. The advocacy of the disability community resulted in a federal assurance that qualified individuals could not be discriminated against based on their disability. Despite the rich and powerful history of advocacy within the disability community, individuals with (versus without) disabilities engage less frequently in civic engagement (Ho et al., 2020). Low levels of civic engagement have been attributed to ableist systemic and infrastructure barriers, which may include the inaccessibility of civic engagement because of an individual’s mobility restrictions, chronic health conditions, and sensory overstimulation at sites for civic engagement (Ho et al., 2020). However, this may also be attributed to limited instruction for students with disabilities about how to vote or participate politically (Agran & Hughes, 2013). In this multi-method pilot study, the research team explored aspects of a new civic-engagement program. Specifically, our research questions were as follows.

- How was the civic-engagement program developed?

- What was the preliminary effectiveness of the civic-engagement program?

- What was the feedback of the individuals with disabilities for the next IDEA reauthorization?

- What was the feasibility and social validity of the civic-engagement program?

Method

Participants

There were two groups of participants for this study: (1) youth with disabilities and (2) Parent Training and Information Center (PTI) staff. Regarding the former, to be included in this study, the participant needed to be between the ages of 12-26 and have an IEP. The age range of 12-26 was chosen as parents often report that transition planning should begin at age 12 (e.g., Francis et al., 2018), and 26 is the highest age that an individual can have an IEP in the U.S. (e.g., Michigan). Regarding the latter, the participant needed to work at a PTI that facilitated the civic-engagement program for this project. Altogether, there were 16 individuals with disabilities in this study. On average, participants were 19.75 years of age (SD = 3.96 , range 13-26). Half of the participants were White (50%, n = 8). Of the participants, 43.75% (n = 7) were from Massachusetts (MA), 25.00% (n = 4) were from Illinois (IL), 18.75% (n = 3) were from Louisiana (LA), and 12.50% (n = 2) were from Maine (ME). Regarding PTI staff, there were eight participants including a director, parent trainer, and self-advocate from ME (n = 3); a director and parent trainer from IL (n = 2); and a director, a parent trainer, and a self-advocate from LA (n = 3). In MA, the civic-engagement program was conducted with a school; thus, no PTI representative was included from MA (see Table 1).

| Individuals with disabilities | PTI staff | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | % | n | % | n |

| Gender: Male | 62.50 | 10 | 25.0 | 2 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 50.00 | 8 | 87.50 | 7 |

| Black or African American | 31.25 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9.09 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian American | 6.25 | 1 | 12.5 | 1 |

| Two or more races | 6.25 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Type of disabilitya | ||||

| Autism | 50.00 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Intellectual disability | 37.50 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Specific learning disability | 31.25 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Speech and language impairment | 25.00 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Other health impairment | 25.00 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Attention deficit disorder | 18.75 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Other disabilities | 18.75 | 3 | 37.5 | 3 |

| Emotional/behavioral disorder | 12.50 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Visual impairment | 6.25 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Down syndrome | 6.25 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cerebral palsy | 6.25 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Recruitment

Recruitment for the transition-aged youth with disabilities to participate in the pilot program in-person occurred in several ways. For example, across the states, PTIs facilitated recruitment efforts by sharing the recruitment flyer with their constituencies and via social media. Flyers were also shared with disability organizations, self-advocacy groups, schools, and family support agencies. Individuals with disabilities were compensated for their participation. Specifically, participants received $25 for completing the pre-survey and $25 for completing the post survey. PTI staff participants were also compensated for their participation, receiving a $25 gift card for completing an interview and a stipend for facilitating the civic-engagement program.

Procedures

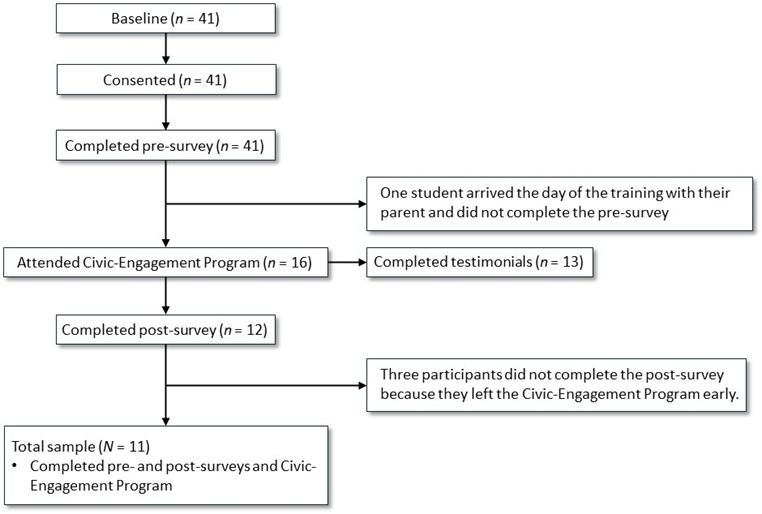

First, the research team received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval at two universities for this study. If an individual was interested in the study, they were directed to a REDCap website wherein they provided consent. Specifically, if the individual was less than 18 years of age and/or had a guardian, their guardian provided consent. If the guardian provided consent, then the individual with a disability was asked to provide assent. If the individual with a disability was over the age of 18 and their own legal guardian, the individual provided consent. After providing consent, the individual completed a pre-survey via REDCap or hard copy, per the participant’s preference. After completing the survey, the individual attended the 6-hour civic-engagement program. After completing the civic-engagement program, the participant completed the post survey via REDCap or hard copy, per the participant’s preference. Also, at the end of the civic-engagement program, the participants were invited to complete a testimonial about their feedback for the next IDEA reauthorization.

PTI staff participation occurred in various ways. For example, at the outset of the project, the research team met with the PTI staff monthly for 1 hour. These meetings were done individually between the research team and each individual PTI site to allow for state-specific feedback. Altogether, there were at least seven monthly meetings with each PTI site, and each meeting was recorded. During the meetings, the research team and PTI staff discussed the civic-engagement program. PTI staff also participated by facilitating the civic-engagement program in ME, LA, and IL; the research team facilitated the civic-engagement program in MA. After facilitating the civic-engagement program, PTI staff participated in a 1-hour, recorded interview about their experience with the civic-engagement program. The interviews were conducted by two university professors at a date/time preferred by the participant.

Measures

Survey Measure: Self-determination Scale

Developed by Shogren et al. (2007), The Arc’s Self-determination scale consisted of 24 items about self-determination. Example items included: “I believe that I can set get goals to get what I want;” and “I know what I need, what I like, and what I’m good at.” Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from “never” (1) to “always” (5). Item scores are summed to form an overall score, with higher scores indicating greater self-determination. Cronbach’s alpha was .97.

Survey Measure: Transition Empowerment Scale

Developed by Powers et al. (2001), this scale was adapted from the Family Empowerment Scale (Koren et al., 1992). The Transition Empowerment Scale measures the extent to which a youth feels empowerment. Example questions included: “I feel that I have a right to approve all services I receive” and “I tell adults what I think about the services and help they give me.” Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from “not at all true” (1) to “very true” (5). Item scores are summed to form an overall score, with higher scores indicating greater empowerment. For this sample, the Cronbach’s alpha was .97.

Survey Measure: Special Education Knowledge

Comprised of 10 multiple-choice questions about special education, this measure has been used with individuals with and without disabilities (Burke et al., 2016). Example questions included: “How often is the individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) updated?” and “At the federal level, what age range does IDEA cover?” Each response was coded “correct” (1) or “incorrect” (0), with potential scores ranging from 0 to 10. Higher scores indicate greater knowledge of special education.

Testimonials

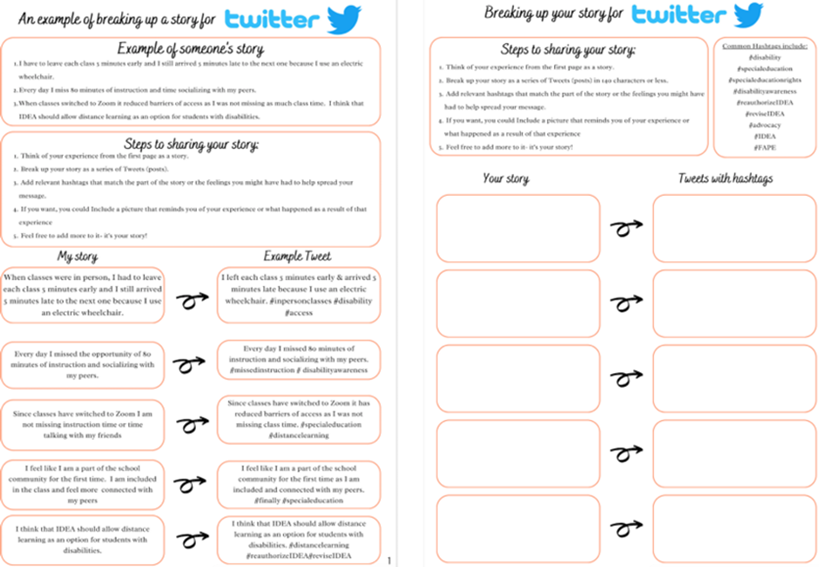

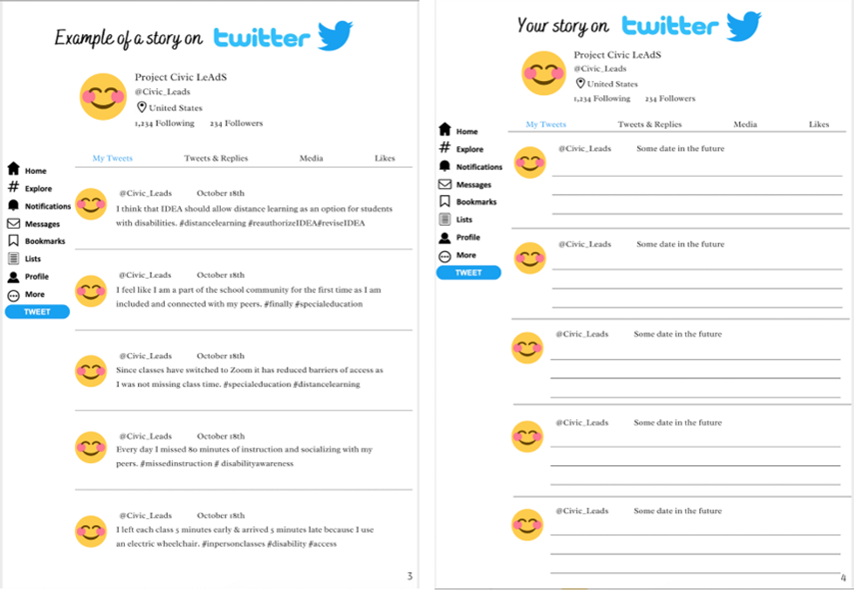

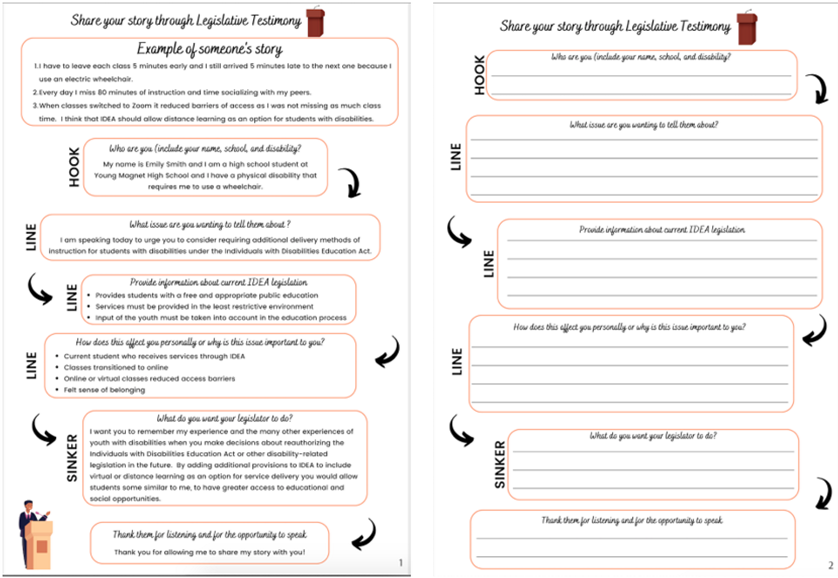

At the end of the civic-engagement program, the youth participants completed a testimonial with their feedback for the next IDEA reauthorization. Participants were given three options to convey their feedback: creating a social media post (e.g., Twitter, Instagram), contacting legislators (e.g., writing a letter), and developing a legislative testimony (e.g., record a video; see Appendix A).

Interview with the PTI

Developed based on extant literature about social validity (e.g., Snodgrass et al., 2022), PTIs (e.g., Burke, 2016) and civic engagement (e.g., Rossetti et al., 2020), the semi-structured interview protocol included six main questions about social validity. The protocol also included planned probes (see Appendix B).

Field Notes During the Civic-Engagement program

During each iteration of the civic-engagement program, at least one researcher recorded field notes. The field notes included observations of the participants and facilitator, impressions about the receipt and implementation of the program, and recognition of the research team member’s own biases.

Attendance and Attrition

During each iteration of the civic-engagement program, attendance was taken. Specifically, there was a sign-in sheet for each site. Attrition was defined as the percentage of participants who started but did not complete the 6-hour civic-engagement program.

Fidelity to the Intervention

During each iteration of the civic-engagement program, at least one researcher completed a fidelity checklist to ensure fidelity to the intervention. Across the four iterations of the civic-engagement program, on average, fidelity was 80%. Specifically, three iterations were completed with at least 80% fidelity. At the ME site, fidelity was 18.18%, as both participants did not complete the entire civic-engagement program. Field notes show that both participants appeared disinterested in the program. The facilitators attempted to explore alternative options to discuss civic engagement (e.g., including movement breaks). Ultimately, both participants communicated that they would no longer like to participate in the program.

Analysis

To determine the preliminary effectiveness of the program, the research team analyzed the pre- and post-survey responses for the Self-determination Scale, Transition Empowerment Scale, and Special Education Knowledge measure. Given the small sample size, the team conducted non-parametric analyses. Specifically, the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test was conducted to determine change from the pre to post survey.

To determine the participant feedback for the next IDEA reauthorization, the research team analyzed the content of the testimonials using a conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The team created a specific coding protocol to identify the type and content of suggested changes to the IDEA (Rossetti et al., 2020). Participants could report more than one suggestion in their testimonials. The coding protocol used a multistage coding process including: (1) identifying the participants’ suggested changes, (2) creating descriptive codes from the participants’ suggestions, and (3) identifying categorical codes (Rossetti et al., 2020). To identify the suggested changes, two independent coders reviewed the testimonials and coded the first three separately. Together, they created a codebook. Then, independently, each coder coded another five testimonials using the codebook. The codes were then compared for the 13 testimonials. Discrepancies were discussed until an agreement was reached. The coding process proceeded with multiple meetings to discuss the codes, reach a consensus on code discrepancies, and to categorize the codes.

Positionality and Reflexivity

The research team was composed of 12 members, including two individuals with disabilities and four family members of individuals with disabilities. Our familiarity with the experiences of individuals with disabilities was a strength in conducting this study and analyzing the data. Specifically, each research team member had knowledge about IDEA policy and advocacy. Further, our co-researchers with disabilities brought their lived experiences with disability to the study. Notably, each team member recorded field notes and engaged in peer debriefing to identify and mitigate biases.

Findings

Development of the Civic-Engagement Program

Initial Adaptation of a Civic-Engagement Program

Developed by the authors, the initial civic-engagement program was targeted for parents of children with disabilities (Burke et al., 2022; Burke & Sandman, 2017). Formatted as a 6-hour program about civic engagement during the IDEA reauthorization, research about the program suggested that it increased special education knowledge, legislative advocacy, civic engagement and empowerment among parents of children with disabilities (Burke et al., 2022; Burke & Sandman, 2017). To adapt the program for transition-aged youth with disabilities, the research team collaborated with disability self-advocates at the PTI, as well as relied on the experience of co-researchers with disabilities on the team. An array of individuals with disabilities provided input on the adaptations, including those with developmental disabilities, including those with autism, and other disabilities such as physical disabilities. The following changes were made: (a) aligning the content with the principles of universal design of learning, (b) offering support persons for the youth with disabilities to attend the program, (c) providing sensory breaks, establishing rapport with the participants (e.g., conducting icebreakers), (d) using plain language, (e) allowing more response time, and (f) using visuals in the curriculum (Hall, 2013; Mactavish et al., 2000).

Pre-Pilot of the Adapted Civic-Engagement Program

In one state, a school contacted the research team to conduct the adapted program with their transition-aged students with cognitive, developmental, and multiple disabilities including intellectual disability and/or autism. The civic-engagement program was facilitated by the research team at the school during a weeknight. Only e hours were available for the program so only half of the program was pre-piloted with the student participants. The participants included six transition-aged youth with intellectual disability and/or autism. All students created a video testimonial at the end of the program. Although no formal data were taken, field notes revealed that the pre-pilot was acceptable to the participants.

Further Adaptation to the Program with Co-Researchers with Disabilities

Recognizing that the pre-pilot was with a small, homogenous sample, the program was further adapted. In this adaptation, the research team included individuals with and without disabilities. Via weekly meetings, the team reviewed the materials, offered feedback for both the content and design of the materials, and shared their impressions of the program. Further adaptations included: adding pictures of individuals with disabilities, enlarging the font size, and incorporating current issues into the content. The adapted materials were shared with the PTI staff which included individuals with and without disabilities. Regarding PTI staff with disabilities, such types of disabilities included physical disabilities, cerebral palsy, and autism. Each PTI provided feedback about the curriculum. The research team utilized the PTI feedback to further revise the program. As a result, the program included two sections: (1) Self-Advocacy and IDEA, and (2) Advocacy and Testimonials.

Virtual Pre-Pilot of the Civic-Engagement Program

The resulting two-section, 6-hour program was pre-piloted via Zoom given restrictions because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of the virtual pre-pilot was to gain feedback on the content of the program. Two research team members (i.e., a self-advocate and a graduate student) facilitated the civic-engagement program. Four youth with disabilities attended this pre-pilot. The four youth had a range of disabilities including: Down syndrome, learning disability, and autism. The remainder of the research team took detailed field notes during the pilot. Notably, the pilot was held over Zoom because of the pandemic.

Further Revisions to the Civic-Engagement Program

As a result of the pre-pilot, several additional changes were made to the civic-engagement program. For example, the slides were revised to reflect accessible colors and font styles. The facilitator notes within the slides were updated to include specific notes and prompts. For example, prompts were added for youth still receiving K-12 services as well as for youth who had aged out or graduated from school. Additional options were provided to facilitate youth engagement. In the virtual pre-pilot, youth were able to access technological features easily as they were using Zoom. For in-person implementation of the civic-engagement program it was also important to facilitate youth engagement. As a result, the research team provided access to iPads to help facilitate youth engagement. To further help facilitate youth engagement, the research team added guided notes to the program. The guided notes were supported by visual images; the guided notes were shared with the program facilitator and the participants allowing both to be reminded of opportunities to pause, reflect, and provide responses to topics or questions. Finally, a facilitator guide was created to support facilitators to conduct the program. The facilitator guide included: links to the civic-engagement program materials, guidance on where self-advocate facilitators could add their own information, tips to facilitate youth engagement, and needed equipment (e.g., iPads).

Preliminary Effectiveness

Self-Determination, Empowerment, and Special Education Knowledge

With respect to transition empowerment, there was a significant increase (p = .004) with a medium effect size. While not significant, there was also an increase in self-determination (p = .066). There was no significant increase in knowledge (p = .187). See Table 2.

| Wilcoxon signed-rank analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Pre | SD | Post | SD | Z | p | r |

| Transition empowerment | 94.73 | 21.93 | 122.64 | 22.97 | -2.85 | .004 | .61 |

| Self-determination | 90.82 | 19.51 | 102.45 | 16.24 | -1.84 | .066 | .39 |

| Knowledge | 3.09 | 1.70 | 3.55 | 1.69 | -1.32 | .187 | .28 |

Testimonials

At the end of the civic-engagement program, youth participants utilized their selected testimonial option (i.e., legislative letter, social media post, legislative testimony) to create a testimonial. The purpose of the testimonial was to provide feedback to legislators that could be sent to legislative representatives regarding improvements to IDEA and the future IDEA reauthorization. At the end of the program, participants had time to write and/or develop the content for their chosen testimonial. All three formats were selected to be used for testimonials. Of the 13 testimonials, 53.85% (n = 7) chose to write a letter that could be sent to a legislator. Of these seven participants, three chose to be video recorded as they read their letters aloud. Four participants chose to create a social media post as their testimonial option. Of these participants, three chose to be video recorded as they read and shared details about their testimonies. Finally, the remaining two participants decided to use prepared legislative testimony that could be shared with legislators. Only one of these participants chose to be video recorded as they read their legislative testimony aloud. Following the civic-engagement program, the research team sent participants their testimonial materials, along with the contact information for their state legislators should they choose to send their testimonial to them. Given the diverse needs of the youth participants, a range of accommodations and supports were provided as needed by adult facilitators such as support with spelling and summarizing ideas.

In all, 53.85% (n = 7) testimonials focused on school experiences (see Table 3). With respect to school experiences, testimonials included suggestions for increased test-taking time, more time for changing clothes before physical education class, and the need for teachers to recognize student independence. For example, Luke shared,

Something that was difficult for me was when teachers followed me around the building, not allowing me to be independent. It upset me a lot and it shouldn’t have to happen to other people. Teachers should know when to help and when to give people independence. #self-advocacy #independency

| Participant | Testimonial theme | Testimonial sample quote |

|---|---|---|

| Lillian | More ramps in schools and public places | “I would like more accessibility for people in wheelchairs” |

| Ellie | Flexible time to change clothes for physical education | “Increase the time to get dressed” |

| Carly | Open access to all high school courses | “Since I am in a special education class I am not eligible to take the math classes that are required to take the Health Occupations class” |

| Henry | Phonics-based reading instruction | “I was not able to read at grade level until third grade, when I was introduced to phonics” |

| William | Increased time during test-taking | “IDEA should allow more time while other people with disabilities should take their tests.” |

| Shawn | Increased consequences for bullying | “IDEA can change schools by making sure… if you keep getting bullied, there will be consequences for the bullies” |

| Omar | Increased oversight for IDEA | “When programs lack, not giving the services, the citizens suffer.” |

| Naomi | Increased access to self-advocacy programming | “I would like this kind of program to be in all countries so this program can help everybody with disabilities” |

| Ian | Autism awareness | “When I get excited, my stimming increases, causing people to stare at me and move away. This makes me uncomfortable” |

| Ryan | College access and inclusion | “I want to see people like me be successful in academics, especially getting a college degree.” |

| Luke | Increased independence in the school environment | “Something that was difficult for me was teachers following me around the building, not allowing me to be independent” |

| Kylen | More affordable housing | “People need help to get good homes” |

| Cooper | City accessibility | “I have noticed that people in wheelchairs, they cannot safely move around” |

The remaining 46.15% (n = 6) of the testimonials reflected issues broader than education. Specifically, other testimonials reflected content about: community accessibility; inclusion for people with disabilities; affordable housing in the community; and access to college experiences for people with disabilities. One youth with Down Syndrome said,

I want to see people like me be successful in academics, specifically getting a college degree… I want to see people like me taking classes for credit, joining clubs, and playing on sports teams like other college students.

Feasibility and Social Validity

Attendance and Attrition

Regarding attendance, 41 participants registered for the civic-engagement program; however, only 16 individuals attended the program. Interviews with the PTI staff helped to elucidate the reasons behind the low attendance. PTI staff reported that the obstacles to attendance included the in-person (versus Zoom) nature of the program and the day of the program. Regarding the nature of the program, many PTI staff commented that, in a post-pandemic culture, the preference for remote meetings and reluctance towards in-person interactions have become prevalent. A PTI staff person reported, “It is post-pandemic, so nobody wants to be in-person.” All the PTIs held the civic-engagement program on a Saturday; the MA site held the program on two weekdays. While MA had the highest attendance (n = 7), the PTIs reported that the day of the program (i.e., Saturday) was problematic. For example, a PTI staff person reported that they held the civic-engagement program on a Saturday in a public-school classroom. Thus, the youth felt they were going to school on a Saturday: a PTI staff person reported, “One of the youths was not happy about that and taking his Saturday.”

The PTI staff had several suggestions for increasing attendance at future civic-engagement programs. For example, PTI staff reported that some youth found the survey overwhelming and the language “confusing.” Accordingly, PTI staff suggested revising the survey to be more youth-friendly and shorter. Logistically, the PTI staff suggested offering the civic-engagement program in conjunction with an already planned event. A PTI staff person reported, “I think that is how it’s going to be, more embedded, not necessarily a training of its own.” To help increase youth retention, participants reported that the program may need to be more engaging. A PTI staff person reported,

For youth, it [instruction] has to be worked into activities. The format of sitting in a room and talking about it doesn’t work. Especially when you are asking about surveys…. It’s not built around somebody talking at them or going through PowerPoint slides.

In total, the attrition rate was 12.5% (see Figure 1). Of the 16 participants who started the program, two participants left during the program and, thus, did not complete the post-survey or testimonial. Notably, both participants were in ME. When asked why the youth left early, a PTI staff person from ME reported,

The full-day training was difficult for the youth to go through…the one-day [training], [with] the anticipation of knowing hours ahead that they still have to do the survey again, I think was the biggest piece of it.”

Social Validity

Both PTI staff and the youth participants reported that the civic-engagement program was important for transition-aged youth with disabilities. All PTI staff (n = 8) participated in a 60-minute post-program interview over Zoom with a research team member that was not present at their PTI site when the program was implemented. PTI staff often reported that the program provided a way for youth to voice their concerns. A PTI staff person reported,

I think that’s important. Just listening to those [youth] perspectives and just allowing people with disabilities to be a part of the conversation. They also appreciated that the participants were compensated for their time. I think it’s a good incentive of the stipend for youth especially.

Regarding the content of the civic-engagement program, PTI staff and the youth reported it was important. While PTI staff participated in a post-program interview, youth gave feedback on their perception and value of the program as part of the post-pilot survey. Indeed, all PTI staff people reported that they planned to use elements of the civic-engagement program in the future. Put simply by a staff person, “I think the content of the [youth] training was really well done. I really actually like a lot of it. And I plan to use many of those pieces in the future.” Another staff person commented on the specific aspects of the program she will use in the future: “The content and the topics [are] something I will be implementing throughout all the work that we do, especially, using the social media and the basics around that is something that I will embed into all the other stuff that I do.” Some youth participants also reported wanting to continue to participate in the civic-engagement program. Indeed, Naomi shared:

I like the self-advocacy program. It’s very helpful. I would like this kind of program to be in all countries so this program can help everybody with disabilities.

Discussion

For any disability legislation, it is critical to secure the feedback of individuals with disabilities. With the looming reauthorization of IDEA and the little engagement from the disability community in previous reauthorizations (York, 2005), it is important to facilitate civic engagement among youth with disabilities. In this pilot project, the research team examined the development, preliminary effectiveness, feasibility, and social validity of a civic-engagement program among transition-aged youth with disabilities. There were two main findings.

First, there is preliminary evidence that the civic-engagement program was effective among transition-aged youth with disabilities. The significant increase in transition empowerment suggests that the program may foster empowerment among youth with disabilities. Prior research suggests that greater transition empowerment can lead to greater self-determination (Shogren et al., 2007). Thus, this finding is promising in terms of the potential effectiveness of the program. Further, this study yielded 13 testimonials about self-advocacy and potential changes to IDEA or other disability policy. Having a product such as written or recorded testimony (e.g., legislative letter, social media, advocacy statement) wherein youth can showcase their feedback to lawmakers is another potential testament to the effect of the civic-engagement program.

However, more research is needed. Without a control group, it is not possible to attribute any effect to an intervention (Campbell & Stanley, 2015). Further, a study needs to be sufficiently powered to discern an effect (Myors et al., 2010); a larger sample can help determine whether the civic-engagement program is effective. To attain a larger sample, future researchers should consider expanding this project to include more PTIs and/or a broader geographic scope. As a next step, it is important to further pilot the program and then conduct a randomized controlled trial that is sufficiently powered to determine whether the civic-engagement program yields meaningful effects among transition-aged youth with disabilities.

Second, there is room for improvement in the civic-engagement program. The low attendance and lack of significant effects with respect to self-determination and knowledge suggest that more revisions are needed to the civic-engagement program. Notably, revisions should aim to increase attendance, self-determination, and knowledge. Regarding the former, logistical issues need to be addressed to improve attendance. Changing the day of the program may help improve attendance. Further, given that MA had the highest attendance, it may be more appropriate to have schools (versus PTIs) be the setting for the program. Mandated by IDEA, PTIs are required to serve parents of individuals with disabilities (Burke, 2016). Of the limited prior research about PTIs (e.g., Cooc & Bui, 2017), none of the research has examined their outreach to individuals with disabilities (versus families). To improve the program, it may also be helpful to examine effective interventions in improving self-determination (e.g., SDLMI, Wehmeyer et al., 2012). Additionally, more piloting of the revised program and materials could be beneficial. Moving forward, it may be important to consider whether the civic-engagement program would be more feasible if offered and implemented in school during the school day.

In addition, the content of the civic-engagement program may need additional revisions. Although there was an extensive adaptation process including input from individuals with disabilities, there seems to be more needed changes. Changes may include imparting accurate information about special education. Prior research with parents of individuals with disabilities has found that the absence of special education knowledge is a barrier to civic engagement (Burke et al., 2018). Thus, it seems important to ensure that youth have a solid understanding of IDEA. The results from this study suggest a poor understanding of special education. This result is underscored by the testimonials wherein many youth suggested that IDEA include certain provisions (e.g., extended test-taking time) even though such provisions are already in the law. The feedback from the PTIs and the poor fidelity in ME suggest that changes to the content of the civic-engagement program may also need to reflect more engaging strategies (versus didactic instruction). Altogether, changes to the civic-engagement program may need to focus on increasing knowledge of special education.

Limitations

Given the nature of this pilot study, there are several limitations which should be considered when interpreting the findings. The sample size was small (n = 16); thus, generalizability of the findings is limited. Further, it is unclear how the initial 41 participants differed from our final sample. Also, the civic-engagement program was implemented by research staff (not PTI staff) in MA. There may be other ways that the MA site differed from the other sites thus explaining differences between sites, such as the program being conducted across two 3-hour days instead of one 6-hour day.

Implications for Research and Practice

There are several implications for future research. First, there is a ripe opportunity for research about transition-aged youth with disabilities, IDEA, and self-advocacy. Our study suggests that youth with disabilities from a range of ages, states, and types of support needs are interested in civic engagement. Research is needed to discern whether the effectiveness of a civic-engagement program is moderated by youth characteristics. Further, research is needed to discern whether feedback for the IDEA reauthorization relates to certain experiences of the youth. For example, in a study of parent feedback for the IDEA reauthorization, parents of individuals with (versus without) autism were significantly more likely to request that IDEA includes applied behavior analysis (Burke & Sandman, 2015). Research is needed to identify whether similar patterns exist among youth with disabilities.

In addition, while this study included only youth with disabilities, research is needed about inclusive civic-engagement programs. Given that inclusive opportunities for youth with disabilities positively impact post-secondary outcomes (Mazzotti et al., 2021; Sprunger et al., 2018), it may be more effective to offer a civic-engagement program to youth with and without disabilities. While the rallying cry of the disability community “Nothing about us, without us” rings true, it does not imply that disability advocacy work should only be done by those with disabilities (Nario-Redmond & Oleson, 2016). Additional civic-engagement research related to IDEA should discern whether an inclusive program is more effective than a program that is solely for individuals with disabilities.

More research is needed that invites and creates space for individuals with disabilities to co-conduct research across a plethora of topics, including local, state, and federal advocacy and policy work (Mmatli, 2009). One way to facilitate this is to include individuals with disabilities on research teams so that interventions include end users and networks can be built that spark systemic change (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2021; White et al., 2021). Relatedly, research is needed to understand the perspectives of researchers with disabilities in working on inclusive research projects. While there are inclusive research projects with co-researchers with disabilities, the viewpoints of researchers with disabilities are often absent or selectively reported (Strnadová & Walmsley, 2018). Further research is needed with researchers with disabilities to ensure interventions and advocacy work centers the voices and experiences of those with disabilities.

Practitioners may consider using the testimonial templates as ways to foster youth civic engagement. These scaffolded templates included examples, structured support for developing testimonies, and a final testimony product (e.g., Instagram, TikTok, legislative testimony). While unintended, the testimonials were broad reflecting feedback for policies beyond education. Thus, practitioners such as adult service providers and transition agencies may consider using the testimonial templates to encourage individuals with disabilities to offer legislative feedback.

Teachers may also consider embedding some content of the civic-engagement program in their instruction. Specifically, teachers may consider educating their students about IDEA and/or offering ways that transition-aged youth with disabilities can participate in civic engagement. Most of the youth were unfamiliar with IDEA at the start of the civic-engagement program, suggesting that instruction is needed about IDEA. Disability history and policy could also be included in K-12 social studies standards, leading to further opportunities for inclusive learning (Cairn, 2023). The inclusion of disability rights, special education law, and the implications for self-advocacy within transition planning and instruction could lead youth to feel more empowered in their knowledge, advocacy, and, ultimately, civic engagement.

References

Agran, M., & Hughes, C. (2013). “You can’t vote—You’re mentally incompetent”: Denying democracy to people with severe disabilities. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 38, 58-62. https://doi.org/ 10.2511/027494813807047006

Bigby, C., Frawley, P., & Ramcharan, P. (2014). Conceptualizing inclusive research with people with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(1), 3-12. https://doi.org/10.1111/ jr.12083

Bottema-Beutel, K., Kapp, S. K., Lester, J. N., Sasson, N. J., & Hand, B. N. (2021). Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions for autism researchers. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 18-29. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut. 2020.0014

Burke, M. (2016). Effectiveness of parent training activities on parents of children and young adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 3(1), 85-93. https://doi.org/10.1080.23297018.2016.1144076

Burke, M. M., Goldman, S. E., Hart, M. S., & Hodapp, R. M. (2016). Evaluating the efficacy of a special education advocacy training program. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 13(4), 269-276. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12183

Burke, M. M., Rossetti, Z., & Li, C. (2022). The efficacy and impact of a special education legislative advocacy program among parents of children with disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(7), 3271-3279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05258-4

Burke, M. M., & Sandman, L. (2015). In the voices of parents: Suggestions for the next IDEA reauthorization. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 40(1), 71-85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796915585109

Burke, M. M., & Sandman, L. (2017). The effectiveness of a parent advocacy training upon legislative advocacy. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 14(2), 138-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12173

Burke, M. M., Sandman, L., Perez, B., & O’Leary, M. (2018). The phenomenon of legislative advocacy among parents of children with disabilities. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 18, 50-58. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/1471-3802.12392

Cairn, R. (2023, July 19). Disability history & Massachusetts 2018 social studies standards. DisMuse. https://disabilitymuseum.org/dismuse/2018-social-studies-standards/

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (2015). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Ravenio.

Chandroo, R., Strnadová, I., & Cumming, T. M. (2020). Is it really student-focused planning? Perspectives of students with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 107, 103783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2020. 103783

Chown, N., Robinson, J., Beardon, L., Downing, J., Hughes, L., Leatherland, J., Fox, K., Hickman, L., & MacGregor, D. (2017). Improving research about us, with us: A draft framework for inclusive autism research. Disability & Society, 32(5), 720-734. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1320273

Cooc, N., & Bui, O. T. (2017). Characteristics of parent center assistance from the federation for children with special needs. The Journal of Special Education, 51(3), 138-149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466917696285

Francis, G. L., Gross, J. M. S., Lavin, C. E., Velazquez, L. A. C., & Sheets, N. (2018). Hispanic caregiver experiences supporting positive postschool outcomes for young adults with disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 56, 337-353. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-56.5.337

Gartin, B. C., & Murdick, N. L. (2005). IDEA 2004: The IEP. Remedial and Special Education, 26, 327-331. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325050260060301

Goddard, C., & Harding, W. (2003). Selecting the program that’s right for you: A feasibility assessment tool. Waltham: Education Development Center, Inc.

Gutierrez, L. M. (1990). Working with women of color: An empowerment perspective. Social Work, 35, 149-153. https://doi.org/jstor.org/stable/23715256

Hall, S. A. (2013). Including people with intellectual disabilities in qualitative research. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 7, 128-142.

Ho, S., Eaton, S., & Mitra, M. (2020). Civic engagement and people with disabilities: A way forward through cross-movement building. The Lurie Institute for Disability Policy.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Hughes, R. B., Garner, K. B., Robinson-Whelen, S., Arnold, K., Goe, R., Hunt, T., Schwartz, M., McDonald, K. E., & Cesal, L. (2020). “I really want people to use our work to be safe”…Using participatory research to develop a safety intervention for adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 24(3), 309-325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629518793466

Johnson, D. R., Thurlow, M. L., Wu, Y. C., Qian, X., Davenport, E., & Matthais, C. (2022). Youth and parent participation in transition planning in the USA: Findings from the national longitudinal transition study 2012 (NLTS 2012). Journal of International Special Needs Education, 25(2), 61-73. https://doi.org/10.9782/JISNE-D-21-00009

Kim, J. H., Hughes, O. E., Demissie, S. A., Kunzier, T. J., Cheung, W. C., Monarrez, E. C., Burke, M. M., & Rossetti, Z. (2022). Lessons learned from research collaboration among people with and without developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 60(5), 405-415. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-60.5.405

Koren, P. E., DeChillo, N., & Friesen, B. J. (1992). Measuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disabilities: A brief questionnaire. Rehabilitation Psychology, 37(4), 305-321. https://doi.org/10.1037/ h0079106

Kucharczyk, S., Oswalt, A. K., Whitby, P. S., Frazier, K., & Koch, L. (2022). Emerging trends in youth engagement during transition: Youth as interdisciplinary partners. Rehabilitation Research, Policy, and Education, 36(1), 71-98. https://doi.org/10.1891/RE-21-16

Mactavish, J., Lutfiyya, Z., & Mahon, M. (2000). ‘‘I can speak for myself’’: Involving individuals with intellectual disabilities as research participants. Mental Retardation, 38, 216–227. https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2000)038<0216:ICSFMI>2.0.CO;2

Mann, B. W. (2018). Autism narratives in media coverage of the MMR vaccine-autism controversy under a crip futurism framework. Health Communication, 34(9), 984-990. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236. 2018.1449071

Mazzotti, V. L., Rowe, D. A., Kwiatek, S., Voggt, A., Chang, W. H., Fowler, C. H., Poppen, M., Sinclair, J., & Test, D. W. (2021). Secondary transition predictors of postschool success: An update to the research base. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 44(1), 47-64. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 2165143420959793

Mmatli, T. O. (2009). Translating disability-related research into evidence-based advocacy: The role of people with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 31(1), 14-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280802280387

Mohr, D. C., Lyon, A. R., Lattie, E. G., Reddy, M., & Schueller, S. M. (2017). Accelerating digital mental health research from early design and creation to successful implementation and sustainment. Journal of Medical Internet research, 19(5), e7725. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7725

Myors, B., Murphy, K. R., & Wolach, A. (2010). Statistical power analysis: A simple and general model for traditional and modern hypothesis tests. Routledge.

Nario-Redmond, M. R., & Oleson, K. C. (2016). Disability group identification and disability-rights advocacy: Contingencies among emerging and other adults. Emerging Adulthood, 4(3), 207-218. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/2167696815579830

National Institute of Mental Health. (2009). Opportunities and challenges of developing information technologies on behavioral and social science clinical research. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health.

Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D., Kapp, S. K., Baggs, A., Ashkenazy, E., McDonald, K., Weiner, M., Maslak, J., Hunter, M. & Joyce, A. (2019). The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism, 23(8), 2007-2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319830523

Powers L. E., Turner A., Westwood D., Matuszewski J., Wilson R., Phillips A. (2001). TAKE CHARGE for the future: A controlled field-test of a model to promote student involvement in transition planning. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 24, 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/088572880102400107

Rim, H., & Kim, J. (2023). Learning disability in adolescence and civic engagement in young adulthood: Uncovering social‐psychological mechanisms. Social Science Quarterly, 104(4), 464-477. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu. 13270

Rossetti, Z., Burke, M. M., Rios, K., Rivera, J. I., Schraml-Block, K., Hughes, O., Lee, J., & Aleman-Tovar, J. (2020). Parent leadership and civic engagement: Suggestions for the next individuals with disabilities education act reauthorization. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 31(2), 99-111. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1044207319 901260

Seekins, T., Shunkamolah, W., Bertsche, M., Cowart, C., Summers, J. A., Reichard, A., & White, G. (2012). A systematic scoping review of measures of participation in disability and rehabilitation research: A preliminary report of findings. Disability and Health Journal, 5(4), 224-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.05.002

Shogren, K. A., & Plotner, A. J. (2012). Transition planning for students with intellectual disability, autism, or other disabilities: Data from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(1), 16-30. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-50.1.16

Shogren, K. A., Wehmeyer, M. L., & Palmer, S. B. (2017). Causal agency theory. In M. Wehmeyer, K. Shogren, T. Little, & S. Lopez (Eds.), Development of self-determination through the life-course (pp. 55-67). https://doi.org/ 10.1007/978-94-024-1042-6_5

Shogren, K. A., Wehmeyer, M. L., Palmer, S. B., Soukup, J. H., Little, T. D., Garner, N., & Lawrence, M. (2007). Examining individual and ecological predictors of the self-determination of students with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 73(4), 488-510. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291408000206

Snodgrass, M. R., Chung, M. Y., Kretzer, J. M., & Biggs, E. E. (2022). Rigorous assessment of social validity: A scoping review of a 40-year conversation. Remedial and Special Education, 43, 114-130. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 074193252110017295

Spear, C. F., Strickland, Cohen, K., Romer, N., & Albin, R. W. (2013). An examination of social validity within single-case research with students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 34, 357-370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932513490809

Sprunger, N. S., Harvey, M. W., & Quick, M. M. (2018). Special education transition predictors for post-school success: Findings from the field. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 62(2), 116-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2017.1393789

Strnadová, I., & Walmsley, J. (2018). Peer‐reviewed articles on inclusive research: Do co‐researchers with intellectual disabilities have a voice? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(1), 132-141. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12378

Valdez, C. R., Abegglen, J., & Hauser, C. T. (2013). Fortalezas familiares program: Building sociocultural and family strengths in Latina women with depression and their families. Family Process, 52, 378-393. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/famp.12008

Wehmeyer, M. L., & Shogren, K. A., (2016) Self-determination and choice. In: Singh, N. (eds) Handbook of Evidence-Based Practices in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (pp. 561-584). Springer.

Wehmeyer, M. L., Shogren, K. A., Palmer, S. B., Williams-Diehm, K. L., Little, T. D., & Boulton, A. (2012). The impact of the self-determined learning model of instruction on student self-determination. Exceptional Children, 78(2), 135-153. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291207800201

White, G. W., Nary, D. E., & Froehlich, A. K. (2021). Consumers as collaborators in research and action. In: Keys, C., Dowrick, P. People with Disabilities (pp. 15-34). Routledge.

Williamson, H. J., Fisher, K. W., Madhavni, D., & Talarico, L. (2019). # ADA25 Campaign: Using social media to promote participation, social inclusion, and civic engagement of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Inclusion, 7(1), 24-40. https://doi.org/10.1352/2326-6988-7.1.24

York, L. A. (2005). Descriptive analysis of comments obtained during the process of regulating the reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004 [Unpublished Dissertation]. Denton, Texas. University of North Texas.

Appendix A: Youth Testimonial Guides

Appendix B: Interview Protocol

- Tell me about how you implemented the civic engagement program (CEP) at your organization- walk me through the process. To implement the CEP, what was needed in terms of:

- Preparation

- Resources

- Processes

- Recruitment

- What would you say are the key components of the CEP?

- Which components do you think are necessary for the CEP to be effective?

- Are specific organizational conditions required for model implementation (e.g., population served, how services are delivered)?

- Which components may be optional?

- Is there anything else you wish you had done as part of the CEP that you didn’t do this time?

- Let’s talk about the technical assistance you received during this process:

- Which components of the webinar series/technical assistance were necessary?

- Which may be optional?

- Do you have suggestions for improving this process?

- Future plans: What are your future plans for the CEP?

- How likely are you to use it again?

- What, if anything would you change?

- Does it work for all parents/families?

- In the future, would you collaborate with researchers again?

- How would you like to collaborate with researchers?

- How should you be compensated in working with researchers?

- What do you want researchers to know about partnering with PTIs?

- Wrap-up: Is there anything else you would like to add?

- Was the amount of time to prepare (e.g., monthly meetings with us, recruitment, actual time for the trainings) what you thought it would be?

- Were the stipends enough?

- What did you think about the recruiting process and the number of parents (and youth) who actually showed up in-person at the trainings? (Why were the numbers so low?)