Exploring Parental Perspectives on the Transition to Kindergarten for Children with Disabilities

Kari Alberque and Somer Matthews

Alberque, K., & Matthews, S. (2024). Exploring parental perspectives on the transition to kindergarten for children with disabilities. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 4(2), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.59620/2694-1104.1088

Plain Language Summary

Moving a child with a disability from preschool to kindergarten can be a tough time for parents. Many worry about whether their child will be able to meet the new academic demands. Some parents feel like they’re not getting enough support and don’t know how to advocate for their child’s needs.

In this project, we wanted to understand what parents of children with disabilities go through during this transition. We wanted to hear about their personal experiences, the challenges they faced, and the help they received from others.

We talked to six parents from a disability support program using video chats. We asked them about their experiences with their child’s move to kindergarten. In this paper, we share what these parents told us and point out some common experiences they had.

From listening to their stories, we noticed that they had many similar experiences. They all struggled to understand the transition process and found it helpful to connect with other parents for support. They also talked about the challenges their children faced in the kindergarten classroom and how their expectations had to change because of their child’s disability.

This study is small, with most parents having children with similar disabilities and being White. It would be useful to also talk to parents of children with different disabilities and from different ethnic backgrounds to get a fuller picture. However, this study does provide valuable insights into what parents go through and could help schools improve the transition process for everyone.

Abstract

This qualitative interview study explores the personal narratives of parents of children with disabilities regarding the transition of their child to kindergarten. Informed by Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, we conducted six parent interviews during the kindergarten year to collect insights about their experiences, challenges, and sources of support. This study aimed to inform the development of effective practices that support families during this critical transition period. Through reflexive thematic analysis, we identified several themes from the data, which include: (1) challenges in understanding the Individualized Education Program (IEP) and the transition process, (2) the value of parent-to-parent support networks, (3) obstacles faced in the kindergarten setting, and (4) perceptions of bias and managing expectations. The study underscores the importance of environmental contexts in these transitions. Key implications from our findings include advocating for enhancing parental support through means such as advocacy training, bolstering peer support, and offering mentorship programs. This research suggests the potential benefits of strategies tailored to the unique needs of families and communities, aiming to foster more effective kindergarten transitions for children with disabilities.

Introduction

The transition from preschool to kindergarten is more than a shift in educational environments—it is a key developmental milestone with potential long-term impacts on school adjustment and overall academic achievement (Eckert et al., 2008; Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000; Slicker et al., 2021). This transitional period is particularly critical for parents of children with disabilities, who often express greater concern about the process compared to families of typically developing children (Fontil et al., 2020; Welchons & McIntyre, 2015). Active family involvement in the transition process contributes to positive outcomes for both children and parents (Gooden & Rous, 2018). Moreover, incorporating family needs and promoting parent participation in the transition process have been identified as essential strategies to ease stress and facilitate a positive experience (Fowler et al., 1991; Haciibrahimoglu, 2022). While many studies address these aspects, the distinct experiences of parents navigating this transition for their children with disabilities remain less comprehensively explored. Situated within the Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), this study seeks to explore the personal narratives of these parents, aiming to contribute to and expand the ongoing discussion, enhancing the collective understanding and informing more effective support strategies for these families during this critical transition.

Parents are not navigating this transition alone; schools and community organizations provide significant support (Pianta & Kraft-Sayre, 2003). Yet, parents continue to face challenges, indicating the need for a more nuanced understanding of their experiences. Parents often express concerns about the compatibility of their child’s readiness with kindergarten expectations (McIntyre et al., 2010; Sands & Meadan, 2023). As families leave the familiar, family-centric preschool environment and establish new relationships at an elementary school (Cowan et al., 2005), parents often assume the role of advocate for their children (Rossetti et al., 2021). Thus, this research aims to delve into parents’ experiences during this transition, focusing on the support they receive and the areas where further assistance may be beneficial.

In the next section of this paper, we elaborate on the connection between Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) Ecological Systems Theory and the transition from pre-school to kindergarten. In subsequent sections, we elaborate on school- and community-based support approaches, parent experiences and perceptions, and the role of parent advocacy during this crucial transition. These sections explore the resources available to parents, the challenges they face, their need for advocacy support, and their multifaceted experiences. These aspects shape the overall parental experience during the transition from preschool to public school kindergarten.

Ecological View of Transition

Informed by Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1979), this study emphasizes the interplay of environmental contexts in understanding parent experience and perspective during the transition to kindergarten for children with disabilities. Bronfenbrenner theorized that interconnected systems, from direct interactions within the family and school (microsystem) to societal influences (macrosystem), shape an individual’s development. As children transition to kindergarten, their immediate surroundings, or microsystem, become essential. Here, parents’ views on their child’s school, teachers, and peers significantly mold their experiences and how best to support those parents. Our research recognizes a range of environmental factors, from immediate family settings to larger societal contexts, that contribute to the transition to kindergarten for children with disabilities.

Researchers have used this theory as a foundation for numerous conceptual models and investigations focused on early childhood transitions (Gooden & Rous, 2018; Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000; Rous et al., 2007; Sands & Meadan, 2023). This ecological perspective provided the foundation for our research questions and data analysis. Through this lens, we explored the influences impacting parents and children to inform support practices, thereby creating positive outcomes for children and families.

Support for Parents During Kindergarten Transition: School-Based and Community-Based Approaches

Parental support in the form of school- and community-based resources plays a vital role in the transition to kindergarten. These resources assist families through the transition and ease the adjustment process for children with disabilities. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) ensures that students with disabilities receive a free appropriate public education with individualized support. This is achieved through the development of an Individualized Educational Plan (IEP) to meet specific student needs. IDEA mandates family participation in IEP development, positioning parents as the primary advocates for their child (Rossetti et al., 2021). Most parents of children with disabilities express a desire to engage in the transition process (McIntyre et al., 2007, 2010; Waters & Friesen, 2019). However, they often feel unsupported in their role as advocates and may lack the necessary experience or knowledge to perform this function effectively (Rossetti et al., 2021).

As children move from preschool to kindergarten, schools implement high- and low-intensity transition practices to support both parents and their children. High-intensity practices necessitate a personalized approach and encompass actions such as phone calls, home visits, and planning meetings. These practices effectively address the unique strengths, needs, and characteristics of individual children and families (Levert, 2023; Rous & Hallam, 2012; Rous et al., 2007). In contrast, low-intensity practices, which are less personalized, typically include activities such as sharing children’s records between programs, encouraging families to meet the staff, arranging family visits to kindergarten, and providing parents with general kindergarten information. However, low-intensity practices, despite being more common, lack individual attention and care intrinsic to high-intensity strategies (Daley et al., 2011; Markowitz et al., 2006).

Community-based resources and organizations, such as disability support groups and federally funded Parent Training and Information Centers (PTIs), provide support to families during the kindergarten transition. These organizations build parent capacity by equipping parents with knowledge and skills that prove beneficial during their child’s transition (Stoner et al., 2007). Specifically, these organizations offer programs that educate parents about the transition process, offer emotional support, and empower them to advocate for their children. For example, some PTIs offer webinars and disseminate comprehensive fact sheets related to the IEP process (Exceptional Children’s Assistance Center, 2023; Maine Parent Federation, 2023). Moreover, other organizations support parents of children with specific disabilities by providing programs that address common goals and expectations, along with explaining proper classroom activity modifications (Down Syndrome Resource Foundation, n.d.).

Parent Experiences and Perceptions

Parents, as primary advocates and experts on their children, play a pivotal role in the kindergarten transition, especially for children with disabilities. Their firsthand experiences provide invaluable insights into effective strategies vital to this significant transition. Rous et al. (2007) identified resources such as workshops and informational guides that clarified the transition process and provided support groups and information on parental rights under IDEA. Quintero and McIntyre (2011) found that professionals used more generic strategies, and they failed to meet the needs of individual families adequately. This lack of individualized and high-intensity transition practices is evident in multiple publications revealing that low-intensity transition practices were far more prevalent than their high-intensity counterparts (Levert, 2023; Markowitz et al., 2006). Sands and Meadan (2023) offered insights from both parents and teachers. In line with the observations of Markowitz et al. and Quintero and McIntyre (2011), parents acknowledged the benefits of high-intensity transition practices such as individualized planning, transition meetings, and direct communication with teachers (Sands & Meadan, 2023). These studies underline parents’ needs and preferences for specific experiences during their child’s entry into kindergarten. Beyond these tangible practices, a need exists for other types of support.

Communication and trust-building are also areas of concern for parents. Stoner et al. (2007) highlighted the crucial importance of clear communication and adequately prepared staff in facilitating a smooth transition. Parents expressed concerns about the lack of specific student information prior to the transition and the unavailability of necessary supportive materials for their children. Additionally, communication challenges extend beyond the parent-staff relationship to within educational settings themselves. Welchons and McIntyre (2015) identified limited communication and collaboration between preschool and kindergarten teachers, emphasizing the need for improved collaboration and more intensive and individualized transition practices for children with disabilities. Consistent with Hutchinson et al. (2014) and Starr et al. (2016), Sands and Meadan (2023) also found that limited communication and collaboration between parents and the incoming kindergarten team, along with delayed information, presented challenges to a successful transition. These communication gaps illustrate the necessity of a systemic approach, where communication channels and coordination among different stakeholders—families, preschools, kindergartens, and community resources—are streamlined and effective.

The Role of Parent Advocacy

Beyond the need for communication and collaboration, parents have expressed a desire for advocacy training and support (Goldman, 2020). This need for advocacy arose from their experiences during the transition, where they felt compelled to protect their child’s rights and ensure adequate services and accommodations. In a study by Stoner et al. (2007), parents reported feeling ill-prepared for the role of advocate, expressing the desire for training and resources to better navigate the education system. Their narratives underscored the challenges they encountered in advocating for their child’s needs, particularly in situations where they disagreed with school staff. Additionally, Haines et al. (2017) found that parents, while wanting to advocate for their children, experienced fear of being perceived as demanding or combative. This fear could potentially prevent parents from engaging fully in the advocacy process, hindering the successful transition of their child to kindergarten. These experiences reveal a complex situation with parents wanting effective practices, transparent communication, robust collaboration, and advocacy support. Seeing the depth and intricacy of these experiences, the discussion now turns to exploring the role of the broader environment in which these transitions take place—the ecological view of transition.

Present Study

Building on this ecological framework, the purpose of this qualitative study was to describe the transition experiences of families who have a child with a disability moving from preschool programs to kindergarten. Through interviews conducted during the kindergarten year, we collected insights about their experiences, challenges, and sources of support. This study aimed to inform the development of effective practices that support families during this critical transition period. The following questions guided the study.

- What are the lived experiences of parents of children with disabilities as their children transition from preschool to kindergarten?

- What specific challenges do these parents face during this transition?

- What supports or resources do these parents utilize during this transition?

- How do these experiences inform the development of support for families as their children with disabilities transition from preschool to public school kindergarten?

Method

Research Design Overview

This study employs a qualitative methodology to investigate the experiences and perspectives of parents of children with disabilities as they navigate the transition to kindergarten. We used semistructured interviews and employed reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2021) to guide our analysis of the interview data. Thematic analysis is a prevalent method used in qualitative research that promotes the identification and interpretation of themes presented by the data. We selected the RTA approach because it prioritizes data quality over data saturation and is well-suited for in-depth analysis of a small sample size (Braun & Clarke, 2021; Malterud et al., 2016). In January 2022, the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina Greensboro approved this study (IRB-FY22-277).

Study Team

I, the lead author, am a master’s-level social worker, special education doctoral student, assistant professor of social work, and parent of a child with an intellectual disability. My personal investment in the research topic has been deep and sustained. I have been directly involved in my child’s transition to kindergarten, have designed and led a kindergarten transition workshop series, and have served as an IEP coach for parents.

The second author, my colleague, is a special education doctoral candidate and a former master’s-level classroom special education teacher. We are both White women who identify as cisgender. We acknowledge and value the significance of intersectionality, especially the interplay between race and disability.

Braun and Clarke (2021) emphasize the value of researcher subjectivity as a resource in reflexive qualitative research. Recognizing and reflecting on our positions and the personal stakes we hold in studying the experiences of parents of children with disabilities during their transition to kindergarten is crucial for the analysis. By deeply understanding and acknowledging our personal and professional stakes in the subject, we aim to enhance our reflexivity and deepen insights into parents’ experiences with the transition to kindergarten for children with disabilities.

Recruitment and Participants

We selected study participants based on the following inclusion criteria: (a) parent of a child with a disability and (b) parent of a child entering kindergarten during the 2021-2022 school year. We recruited participants from a kindergarten transition parent support program offered by two non-profit organizations located in Raleigh, North Carolina. The program took place from January through May 2021. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, they delivered this program entirely online.

The goal of the program was to prepare and support parents of children with disabilities during the transition to kindergarten. The support program included the following.

- Informational Workshops: Topics covered included understanding the rights of both the parent and child, creating a vision for the child’s future, advocating for inclusive general education settings, and participating in panel discussions with parents who have experienced the kindergarten transition.

- IEP Coaching Sessions: Program staff met with parents to discuss objectives for the transition IEP meeting and strategies to advocate for their child’s needs effectively.

- Support during the Transition IEP Meeting: Program staff attended IEP meetings, offering emotional support or directly advocating on behalf of the parents and child, which may have included lobbying for particular supports, services, or placements.

Parents could access any component of the program free of charge. However, program staff required parents seeking support during the IEP meeting to attend all informational workshops and an IEP coaching session. An overview of participant engagement with program components prior to study participation is outlined in Table 1.

We distributed a recruitment email containing a hyperlink to a screening questionnaire to the entire group of 24 parents engaged in the program. From this pool, six parents provided responses that aligned with our inclusion criteria, comprising the entire sample. It is worth noting that among these six parents, five had children diagnosed with Down syndrome, while the remaining parent’s child had a developmental delay and was diagnosed with Attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Further elaboration on participant characteristics is presented in Table 1.

| Participant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age range | 25-34 | 35-44 | 35-44 | 35-44 | 35-44 | 25-34 |

| Race and ethnicity | White | White | White | White | White, Latino | White, Black, Native American |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female |

| Employment status | Not working outside the home | Working full-time | Working full-time | Working full-time | Working part-time | Working

Full-time |

| Marital status | Married | Married | Living with partner | Married | Married | Married |

| Child diagnosis | Down syndrome | Down syndrome | Down syndrome | Down syndrome | Down syndrome | Developmental delay and ADHD |

| Child gender | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female |

| Preschool setting | General education classroom

At public school |

Special education classroom; public school | General education classroom at public school | General education classroom at public school | Special education classroom; community preschool | Private preschool with services with itinerant services from public school |

| Kindergarten setting | General | General | General | General education and special education | General | General |

| Received support during IEP meeting | X | |||||

| Received: IEP coaching session | X | X | ||||

| Attended workshop: exploring parent and child rights | X | X | X | X | ||

| Attended workshop: developing a vision | X | X | ||||

| Attended workshop: advocating for inclusive education | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Panel discussion with parents of older children | X | X |

Data Collection

As the lead author, I developed an interview guide with open-ended questions targeting (a) the experience of caregivers, (b) the caregivers’ needs during their child’s transition to kindergarten, and (c) barriers and facilitators faced by the caregivers. Academic advisors with expertise in early childhood and special education, leaders of the transition parent support program, and a parent of a young child with a disability provided feedback on the interview guide. After integrating their feedback, I conducted a pilot interview with a parent, refining the interview guide (see the Appendix) based on this feedback.

Prior to the interviews, participating parents completed a demographic survey and provided informed consent. Between February and April 2022, I carried out semistructured interviews ranging from 50 to 90 minutes each. These interviews were conducted remotely via Zoom, which recorded and initially transcribed the discussions. These sessions were recorded and transcribed, with me verifying each transcript against its recording for accuracy. Field notes were taken during and after each interview. All transcriptions were de-identified for confidentiality, with real names substituted for pseudonyms ahead of analysis.

Data Analysis

We used the reflexive thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2021), which includes six phases: (1) becoming familiar with the data; (2) coding data; (3) generating initial themes; (4) developing and reviewing themes; (5) refining, defining, and naming themes; and (6) writing up results.

In the initial phase, I watched each interview within a week of its completion and revisited them after concluding all interviews. The second author independently watched the interviews and read the transcripts after the completion of all data collection activities and transcription cleaning. Each of us wrote down our reflections, thoughts, and impressions in memos and referred to these notes during our analysis. Subsequently, we convened to discuss our individual observations documented in the memos.

Next, during the coding phase, we uploaded the transcripts into ATLAS.ti (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2022) and collaboratively coded the first transcript. Thereafter, each of us independently coded the rest of the transcripts, applying existing codes and identifying new ones. Regular meetings facilitated discussions about any coding discrepancies, which in turn influenced our subsequent coding and theme identification.

Upon finishing the coding, I clustered codes by likeness, scouring the data for patterns (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This led me to outline a set of preliminary themes, supplemented with fitting participant quotes. The second author and I then came together to debate these initial themes, gauging their alignment with our data, and making necessary revisions. We then articulated theme descriptions, capturing the core of each theme (Braun & Clark, 2006), and set clear criteria for each theme’s scope. We continued analysis during the writing stage, where we refined themes and acknowledged data that diverged from the established themes

Methodological Integrity

Consistent with Braun and Clarke’s (2021) 15-point quality checklist for conducting reflexive thematic analysis, we incorporated practices to ensure the rigor of our study. This involved careful transcription of audio recordings for accuracy, treating all data with equal consideration, and cross-verifying themes with the original data set. We attempted to interpret rather than simply summarize the data, and we made sure that our analysis aligned with the collected data set. We were transparent about our assumptions and our approaches to thematic analysis.

We also engaged in researcher triangulation: both authors independently coded the transcripts, and we then discussed and compared our insights. Conversations about the interview transcripts and the experiences of conducting the interviews added depth to our understanding of the data. Although we understand that qualitative analysis inherently does not yield a single, objective truth (Braun & Clarke, 2021), the use of researcher triangulation allowed us to paint a richer picture of parents’ experiences with their children’s transition to kindergarten.

Results

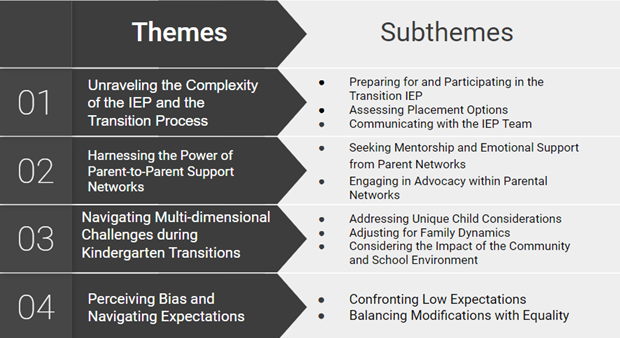

We describe four themes from our interview analysis in this section. We reviewed all transcripts individually, coded them, and then compared our codes. From this process, we developed four main themes, each with its subthemes, that shed light on parents’ perceptions during their children’s transition from preschool to kindergarten. Figure 1 presents a summary of the findings that will be further described in detail.

Theme One: Unraveling the Complexity of the IEP and the Transition Process

Theme one focuses on the challenges parents encounter while transitioning their children with disabilities to kindergarten, such as deciphering regulations, readying for IEP meetings, securing external assistance, advocating for their children’s needs, and deciding educational environment preferences.

Preparing for and Participating in the Transition IEP

While preparing for and participating in the transition IEP meeting, parents expressed a range of emotions and challenges, as well as the need for support and resources. One parent described her experience as overwhelming, saying:

I don’t think I breathed a lot in the few weeks before the meeting. I felt good about all the things I learned [from the parent support program]. I had a strong vision statement. We had concerns [to share with the IEP team]. We had data [to support our preferences], and arguments to every piece. But I still didn’t feel really prepared. There’s just so many components and so many layers of things you have to know and prepare for with those meetings.

Parents described how understanding the IDEA increased their feeling of preparedness for the transition IEP process. One parent discussed being prepared for the complexities of the IEP process by stating, “…. knowing the law and knowing all the information [parent and child rights] is important for a parent to learn going into the kindergarten [transition] meeting.” Parents also emphasized the importance of accessing resources and support to navigate the complex landscape of the transition IEP process. One parent shared their strategy, saying,

I just read a lot. I attended every webinar I could and joined Facebook groups [support groups moderated by state organizations] because we [parents in her area] don’t have a local organization to help me through it [preparing for the transition meeting]. I relied on those resources.

This quote exemplifies the importance of parents finding support through various channels, including online communities and webinars, in the absence of local organizations.

Assessing Placement Options

Parents evaluated various school options (e.g., public, charter, private, and home schools) by considering factors such as the quality of the schools and the availability of resources. One parent opted for a charter school, citing the school’s accommodations and required parental involvement, which allowed them to support the school and connect with staff, teachers, and other parents. Another parent considered private school but ultimately decided on public school, believing their child would have access to more resources and services. These examples show how parents thought about the advantages and disadvantages of each school option in relation to their child’s needs.

Parents explored different classroom settings (e.g., general education, resource, or separate special education settings) and reported being determined to find the best setting for their child’s education and future success. All parents wanted general education settings for their children. One parent shared, “I was 100% pulling for general ed,” and another believed the challenge of a general education classroom would benefit their child more than a self-contained classroom, stating, “I would rather her have to work at it.” Advocacy was pivotal for parents to secure their child’s preferred placement. One parent noted: “I went in knowing what I wanted, and then I had a bottom line for what I was willing to accept for inclusion.” Another parent emphasized the importance of their child’s progress, stating, “I knew she was going to make good progress if she goes to general ed.” In addition to considering their preferences, parents navigated the IEP team decision-making process, where the team assigned varying levels of weight to parent preferences. Although they achieved some successes in advocating, parents still encountered disappointment when the team did not fully consider parents’ preferences. As one parent expressed, “It was a win, and it was a victory, but it also still felt disappointing.”

During this time, parents also faced the decision of whether to retain their children in preschool and/or kindergarten. From the parents’ perspective, while the primary consideration should be what is best for the child, financial implications complicated the decision about retention in preschool. Specifically, with preschool retention, the child receives itinerant services but no longer qualifies for free preschool. During the first half of the kindergarten year, parents reported having conversations with teachers about kindergarten retention. Parents perceived the school was prioritizing the parents’ preference for kindergarten retention. We interviewed parents during the kindergarten year; as a result, we did not collect data on the outcomes of these decisions.

Collaborating and Communicating with the IEP Team

Parents discussed the importance of effective collaboration and communication with the education team to support their child’s transition to kindergarten. Parents viewed building positive relationships with school staff, holding the school accountable, and being active IEP team members as essential to ensuring their child receives the support and accommodations they need during the transition. Several parents adopted a proactive approach when interacting with school staff, addressing concerns before the transition IEP meeting. One parent shared,

I did contact the elementary school staff because they provided some pre-K students, including my child, with the opportunity to experience the kindergarten class. I realized this was their way of collecting data on her in that environment.

The parents highlighted their role as vital members of the IEP team, providing unique insights into their child’s strengths, challenges, and preferences. One parent stated,

[IEP development] is so much to understand. And you need to know how to maintain good relationships with the school when you’re fighting for something they don’t do and don’t want to do.”

This quote underscores the need for parents to have the skills and knowledge to communicate with the school team effectively. A parent suggested emphasizing the importance of collaboration and compromise from the beginning can create a positive and supportive environment for everyone involved. One parent said, “You know, teachers want good things for your child, and they want to see your child succeed.” Those parents who held a high level of trust and confidence in the IEP team generally felt that the team members acted in their child’s best interest.

Study participants emphasized the significance of involvement in the classroom and the establishment of positive relationships with teachers and support staff as key elements for effective collaboration. For instance, one parent took the initiative to educate their child’s classmates about Down syndrome, which resulted in a more understanding and supportive school environment. Another highlighted the value of open communication, using tools like email and shared online documents to keep abreast of their child’s progress.

However, some challenges arose in ensuring that their children received the proper support and accommodations. One parent recounted having to furnish resources on Down syndrome and inclusive education practices because of an evident gap in knowledge within school. This accentuates the crucial role parents play in advocating for their child and collaborating diligently with the educational team to pinpoint effective solutions. Echoing this sentiment of collaboration, a parent underscored adopting a “yes and” approach rather than a “yes, but” stance to lay a cooperative groundwork. Many other parents resonated with this perspective.

Theme Two: Harnessing the Power of Parent-to-Parent Support Networks

The shared experience of navigating early childhood special education can lead to strong connections between parents. “My biggest and best resource has been other moms of kids with Down syndrome,” reported one participant, highlighting the depth of the support they received.

Seeking Mentorship and Emotional Support from Parent Networks

All the parents described seeking and receiving support from parents of older children with disabilities. In these relationships, the parents of older children served as mentors, providing guidance and advice based on their lived experiences. Parents described receiving mentoring support from a community of parents specifically related to the IEP meeting. For instance, one participant commented,

I know another mom, who has done a lot of IEPs and she knows a lot of tips and tricks, and so I feel like I’ve got a good network of people I can leverage if I needed to.

This concept was echoed by another parent who described benefiting from “lessons” learned from mentor parents. She stated,

When you’re coming into it [kindergarten transition], emotions are right there. It feels so big. To have someone who’s a little more removed from it, but has been where you are, is super valuable.

This parent described the value of experiences shared by parents who were “able to get what they wanted” for their child and from those who “weren’t able to get it.”

In these connections, parents also found help with envisioning the future for their children. These visions served as a roadmap to navigate the special education system and advocate for their children’s needs. Notably, these connections not only provided emotional support but also empowered the parents to become stronger advocates for their children.

Engaging in Advocacy within Parental Networks

Three parents highlighted the vital role other parents played as advocates during their child’s transition to kindergarten. These advocates, also parents of children with disabilities, offered pro-bono services ranging from preparing for IEP meetings to supporting during these meetings and extending emotional encouragement. One succinctly expressed her gratitude: “She talked to me on the phone… and just encouraged me and told me what I needed to do [in specific situations].”

Another parent, whose first language was Spanish, emphasized the importance of her advocate, especially when navigating U.S. special education laws. She felt the advocate empowered her to speak freely about her child’s rights and needs. Her metaphor from Mexico – “they would have put the finger on my mouth”—poignantly depicted the silencing she might have felt without her advocate.

A particularly compelling story came from a parent whose child attended a special education preschool. Her advocate suggested she create a vision for her child’s future, a step she had not previously contemplated. This vision became a central discussion point for their transition IEP meeting. The school initially rescheduled the meeting when the school learned of the advocate’s participation. At the reconvened meeting, the advocate astutely observed the absence of a current general education teacher. Through the advocate’s persistence, they secured the attendance of a general education kindergarten teacher. This parent believed her child’s successful transition to a general education classroom was because of the advocate’s efforts. Reflecting on her advocate’s impact, the parent shared, “That’s what I want to be one day. I want to be like her one day.” Her words not only emphasize the advocate’s significant influence but also suggest the profound desire she felt to support other parents in the future.

The collected narratives emphasize the transformative role of parent-to-parent relationships during the pivotal transition to kindergarten. These bonds, characterized by mentorship, advocacy, and emotional reinforcement, fortify parents in their quest to confidently and effectively navigate the multifaceted special education system.

Theme Three: Navigating Multi-Dimensional Challenges During Kindergarten Transitions

Parents consistently highlighted the various challenges that arose during the transition to kindergarten. They emphasized the necessity of understanding their child’s individual requirements and navigating complex situations tailored to those needs. This theme is organized into three subthemes: unique child considerations, family dynamics, and community and school environment.

Addressing Unique Child Considerations

For many parents, the paramount concern was recognizing their child’s specific characteristics and requirements during the transition. As one parent stated, “This is about what’s best for my child. What does she need?” Another parent echoed this sentiment, noting, “He’s got to have a lot of adaptations. He’s got a one-on-one aide, modified materials, and an adapted curriculum.”

There were pronounced worries about children fulfilling kindergarten expectations: mastering independent toileting, developing verbal communication, engaging in social interactions, and transitioning between activities. One parent expressed her child’s difficulties in social situations, “Socially it’s been harder…she gets overwhelmed with other kids around.” Another pointed out the challenges faced by her child due to frequent transitions during the day, stating,

It’s just a long day for kiddos. They change classes and have a really tight schedule. I think having to transition all the time means just as she gets adjusted and acclimated, she’s got to go do something else.

Certain parents spotlighted detailed concerns. A significant one was the child’s ability to manage basic tasks, such as opening lunch packages. One parent remarked,

You know they [teachers] talk about all the things you should work on in the summer to get your kindergartener ready. For example, opening packages in their lunch and managing toileting independently. Those weren’t really options for us. My child doesn’t even have the hand strength to open the things he eats every day.

The topic of toileting was a common concern, encapsulated by one participant who conveyed the intricacies involved:

How do we remind professionals [teachers and direct care staff] that toileting is challenging on all different levels? And no matter where a child is in the process, they could be trained. It is not just reminding kids to go potty. It is an overall process. For example, if my child does a number two, she struggles to wipe herself. I’m not sure what you can ask the school to help with regarding toileting. It’s really tricky and every school is different and nobody knows what they can and can’t do. So, some resources on toileting are critical when transitioning between preschool and kindergarten. It is really tough.

While parents are deeply attentive to their child’s distinct needs during these transitions, it’s clear that outside factors, especially family dynamics, add layers of complexity.

Adjusting for Family Dynamics

The data indicated that family circumstances profoundly influenced the transition experiences shared by the parents. Divorce, for instance, emerged as a particularly challenging circumstance during the transition. One parent detailed their navigation through a complex divorce, asking, “What do you do in situations where you’re going through a divorce and they’re spending time with their dad so he has them on Wednesdays and every other weekend?” This parent further inquired about the tactics and tricks professionals might offer to enhance communication when “you have kids with communication challenges.” From this experience, it became evident that parental divorce could lead to fragmented routines for children, especially with the challenge of splitting time between households. The interview data underscored the heightened difficulty in maintaining consistency, particularly for children with communication difficulties.

Another challenge that parents faced was language barriers, especially when engaging with essential educational documents. A Spanish-speaking parent illustrated their struggle in interpreting and understanding IEP materials, sharing that there were “words… like some words you have never heard” and that their “language is not English.” This parent further described their attempts to understand, saying, “I was trying to go with my dictionary; I was trying to go to the translator [phone app].” The experiences shared pointed to linguistic challenges as significant factors during the transition, highlighting the potential necessity for more accessible, multilingual resources.

Family composition and its dynamics also played a critical role in shaping parents’ experiences. One parent vividly conveyed the intricacies of managing their responsibilities amidst demanding schedules, “It is, I will say it is because…I work full time and I have another daughter who’s 4. We are so busy with both kids.” This narrative emphasized the vital need for support systems that are flexible and accommodating, especially for families juggling work commitments with the needs of multiple children with diverse requirements.

Considering the Impact of the Community and School Environment

Parents consistently pointed to the influence of the community and school environment on their transition experiences. Particularly for those residing in rural areas, geographical distance stood out as a formidable challenge. One parent highlighted the rural nature of their community, explaining, “We are really spread out.” This necessitated seeking services outside their local community. The parent elaborated, “We count ourselves [as part of] the whole region,” sharing further that they frequently journeyed to neighboring towns and counties for family support meetings. They optimistically noted, “There’s some good things happening there, and there are some people who have some helpful information there.” Moreover, a significant byproduct of residing in such areas was the lack of proximity to specialized medical services. As one parent vividly depicted, “Where we live, we have to drive…an hour and a half drive either way because we just don’t have it around here.”

Staffing challenges emerged as another significant theme in the interviews. Parents expressed that high turnover rates and understaffing disrupted their children’s socialization and adjustment experiences. Echoing this sentiment, a parent stated, “It’s very hard; he bonds to certain people, and their absence can really disrupt things for him.” Another parent voiced their dissatisfaction about their district, mentioning, “Our district is having a lot of trouble, and a lot of staff left.” The importance of continuity with school staff was underscored by comments about losing key advocates for their children. A poignant example came from a parent who revealed, “The principal, who has been on our side through all this, is also leaving, which is very concerning.” Another parent emphasized the significance of consistent relationships, noting, “She needs some continuity because she’s always getting new teachers and new therapists.”

One challenge some parents faced was navigating school environments unfamiliar with the inclusion of students with low-incidence disabilities like Down syndrome. A participant shed light on this, saying, “We are really the first people in our county to ever try or ask for them to put her in a regular gen-ed class. We got a lot of pushback on it.” These testimonies suggest a broader challenge of pioneering inclusive practices in educational environments that may lack prior experience or training in accommodating diverse needs. Elaborating on the importance of an inclusive mindset, another parent articulated,

Inclusion can only happen if the teachers are understanding and receptive to it. If you have a teacher who thinks your child shouldn’t be there, or they don’t have the capacity because they’re already so overburdened, they’re just going to throw the book [on inclusive practices] away.

These narratives emphasize the breadth and depth of the challenges parents face during the kindergarten transition, from the unique needs of their child, the intricacies of family dynamics, to the impact of community and school environments. As parents wrestle with these multi-dimensional challenges, another overarching issue emerges—confronting societal biases and the mismatched expectations they foster, leading us to our fourth theme.

Theme Four: Confronting Disability Bias and Navigating Expectations

Parents described a kindergarten transition process where they frequently perceived biases against their children’s abilities. These perceived biases shaped their experiences, compelling them to navigate and reframe the expectations they and others held. The theme consists of two interrelated subthemes: confronting and reassessing expectations, and balancing modifications with equality.

Confronting and Reassessing Expectations

Parents felt that the school system often held low expectations for their children, primarily due to perceived biases. One parent expressed, “Some people just kind of shrug, and they don’t expect much from her.” Another parent elaborated, “[people do not] expect much from her because she has Down syndrome.” At the same time, there were situations where parents felt that unrealistic expectations were placed on their children by school staff, suggesting an inconsistent understanding of their specific needs and abilities. As one parent indicated, “People [school staff] freak out and they either give you anything you want or they’re not even close to being level-headed about an expectation for her.” Highlighting the need for a balanced perspective, another parent advised schools to celebrate what a child can do, adding, “What I qualify as a win for her is probably different than a standard kid.”

Balancing Modifications with Equality

Amid these wide-ranging challenges, parents had to strike a delicate balance between advocating for necessary modifications and ensuring their children’s equal treatment. One parent aptly captured this struggle, saying, “I want her treated like every other kid, but we do have to make some modifications or she’s going to check out.” The sentiment underscores emphasizing the importance of individualized support that does not compromise inclusivity and equality.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the experiences of parents as their children with disabilities transitioned from preschool to public school kindergarten. Through parent narratives, we identified concepts previously recognized in the literature and introduced new insights. The familiar concepts these parents reported included challenges faced during transitions (Stoner et al., 2007), the significance of community and school support activities (Kraft-Sayre & Pianta, 2000), and the vital role of peer support (McCrossin & Lach, 2023). Unique insights from our study revealed that parents not only relied on other parents for mentorship and emotional support, but parents of older children often took on advocacy roles, directly assisting study parents at the IEP table to advocate for inclusive settings for their children. Significantly, this advocacy was often necessary because of challenges related to external factors, which were unrelated to the child’s specific needs or capabilities.

Central to these insights was the process of educational placement decisions. Parents in our study reported these decisions being influenced by numerous factors, including a school’s familiarity with inclusive education and the prevailing biases against individuals with disabilities. Navigating this landscape, parents balanced their child’s specific needs while also considering potential educational environments and available resources. Their experiences supported the assertion by Giangreco et al. (2010) that the successful inclusion of students with disabilities often depends more on the attitudes, skills, and practices of the adults in the educational system than on the specific characteristics of the child.

The parents perceived their role as more than just guardians; they saw themselves as advocates. Their involvement in parent-to-parent networks, which offered not only emotional support but also guidance and a platform for collective advocacy, bolstered this viewpoint. This sense of community and mutual assistance is in line with findings from prior research, notably by Gooden and Rous (2018). Along their advocacy journey, many of our parents, resonating with sentiments expressed by Hutchinson et al. (2014), articulated a pressing need for more resources and training, highlighting the importance of preparing them for robust advocacy.

Viewing the transition from an ecological lens that considers the interplay of environmental contexts (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), our parents painted a vivid picture of the transition process’ multifaceted nature. The success of their child’s transition was not the result of isolated factors but a confluence of influences–from educators, administrators, and community stakeholders—to broader societal attitudes. Our findings underscore the narratives of parents who leaned on other parents and utilized transition resources both school- and community-based. Ultimately, these narratives emphasize the profound interconnectedness of all stakeholders in facilitating a successful transition and underscore the critical role parents play in weaving together these diverse threads for their child’s benefit.

Implications for Supporting Parents

Examining the transition from preschool to kindergarten from the parents’ perspective reveals that, while parents exhibit considerable strengths and resilience, they also encounter barriers in navigating the process and advocating for their preferences. Examples of barriers include challenges faced during transitions, biases against disabilities prevalent in schools and communities, inadequate community and school support, a perceived lack of clarity about educational rights, the attitude of educational institutions towards inclusive education, and linguistic barriers that can hinder effective communication and understanding. When supporting families through this transition, schools and community organizations should build upon the strengths of these families and provide services to address the barriers that exist.

It is notable that while the parents in our study actively sought support, not every family had the means or opportunity to do so. This discrepancy underscores the need for more accessible resources and interventions, ensuring that all families’ priorities, especially regarding placement decisions, are both recognized and addressed.

Based on these insights, our findings suggest the following.

- Advocacy Skills Training for Parents: Parents often wish to advocate for their child’s educational rights but can struggle with complex systems. By offering training focused on advocacy skills, schools and community organizations can empower parents to champion their child’s unique educational needs.

- Peer Support and Mentorship Programs: Our research consistently showed parents valuing peer connections. By creating formal peer support programs, practitioners can reduce feelings of isolation and promote a sense of community.

- Recognition of External Challenges: We identified systemic challenges like biases in the educational system, disparities in resources, resistance to inclusion, and staffing issues. Schools and community organizations must adopt strategies that are responsive to the unique strengths and needs of the families and communities they serve.

Strengths and Limitations

This study offers an in-depth exploration of parental experiences, drawing on the unique perspectives of researchers who are parents and special education professionals. Still, there are several limitations in such a small qualitative study. One obvious limitation is the lack of a diverse sample as four out of six of our participants were White. Notably, our participant group primarily comprised parents of children with Down Syndrome (five out of six participants). This demographic detail provides a deeper understanding of the experiences associated with this specific diagnosis. However, it also suggests potential limitations regarding the broader applicability of the findings to parents of children with other disabilities.

The study also has limitations around bias. Although we have attempted to mitigate bias by acknowledging our positionality as authors, our personal investment in the subject could lead to bias. Further, the retrospective nature of accounts inherently allows for recall bias. Parents might inadvertently omit, misremember, or reinterpret prior events based on their current emotions or subsequent experiences. Additionally, the geographical specificity of the participants may pose a limitation. Given that we derived our sample from a specific region, the findings might not capture the nuanced experiences of parents in different geographical or cultural settings.

Furthermore, the prior involvement of all participants in kindergarten transition support programs offered by two non-profit organizations may have also influenced their perspectives. This involvement could have shaped their experiences and expectations, possibly making them more informed or optimistic about the transition process compared to parents who did not have similar opportunities.

Recognizing these constraints is essential when interpreting our study’s findings and their potential generalizability. Future studies could aim to address these limitations by targeting a more diverse sample or utilizing real-time data collection methods.

Conclusion

In our study, using an ecological framework, we delved into the experiences of families with a child with a disability transitioning from preschool to kindergarten. Through the interviews, we gained insights into the challenges parents encounter and the support resources they utilize. Our findings highlight the vital role of parents in both educational decisions and in leveraging community and peer resources. This research underscores the interconnected factors affecting these transitions and the importance of understanding them in depth. As we consider next steps, this comprehensive perspective is essential to better assist families. Continued research should delve deeper into the challenges parents face during the transition of their child from preschool to kindergarten paving the way for more targeted support interventions.

References

ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. (2022). ATLAS.ti Web (v3.15.0) [Computer software]. https://atlasti.com

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., Ablow, J. C., Johnson, V. K., & Measelle, J. R. (2005). Family factors in children’s adaptation to elementary school: Introducing a five-domain contextual model. In P. A. Cowan, C. P. Cowan, J. C. Ablow, V. K. Johnson, & J. R. Measelle (Eds.), The family context of parenting in children’s adaptation to elementary school (pp. 3-32). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/ 9781410612885

Daley, T. C., Munk, T., & Carlson, E. (2011). A national study of kindergarten transition practices for children with disabilities. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 26(4), 409–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq. 2010.11.001

Down Syndrome Resource Foundation. (n.d.). Kinder kick-off: Kindergarten readiness program. https://www.dsrf.org/programs-and-services/group-programs/kinder-kick-off-kindergarten-readiness-program

Eckert, T. L., McIntyre, L. L., DiGennaro, F. D., Arbolino, L., Begeny, J., & Perry, L. (2008). Researching the transition to kindergarten for typically developing children: A literature review of current processes, practices, and programs. In D. H. Molina (Ed.), School psychology: 21st century issues and challenges (pp. 235–252). Nova Sciences. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255787550_Researching_the_transition_to_kinder garten_for_typically_developing_children_A_literature_review_of_current_processes_practices_and_programs

Exceptional Children’s Assistance Center. (2023). Transition from special education preschool services to kindergarten. https://www.ecac-parentcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Transition-to-Kindergar ten-Fact-sheet_05042023.pdf

Fontil, L., Gittens, J., Beaudoin, E., & Sladeczek, I. E. (2020). Barriers to and facilitators of successful early school transitions for children with autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(6), 1866–1881. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10803-019-03938-w

Fowler, S. A., Schwartz, I., & Atwater, J. (1991). Perspectives on the transition from preschool to kindergarten for children with disabilities and their families. Exceptional Children, 58(2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 001440299105800205

Goldman, S. E. (2020). Special education advocacy for families of students with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Current trends and future directions. In R. M. Hodapp & D. J. Fidler (Eds.), International review of research in developmental disabilities (pp. 1–50). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/ bs.irrdd.2020.07.001

Gooden, C., & Rous, B. (2018). Effective transitions to kindergarten for children with disabilities. In A. J. Mashburn, J. LoCasale-Crouch, & K. C. Pears (Eds.), Kindergarten transition and readiness (pp. 141-162). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90200-5_6

Giangreco, M. F., Carter, E. W., & Doyle, M. B. (2010). Supporting students with disabilities in inclusive classrooms: Personnel and peers. In R. Rose (Ed.), Confronting obstacles to inclusion (1st ed., pp. 247-263). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203846780

Haciibrahimoglu, B. Y. (2022). The transition to kindergarten for children with and without special needs: Identification of family experiences and involvement. International Journal of Progressive Education, 18(2), 104-118. https://doi.org/10.29329/ijpe.2022.431.7

Haines S. J., Francis G. L., Mueller T. G., Chiu C. Y., Burke M. M., Kyzar K., & Turnbull A. P. (2017). Reconceptualizing family-professional partnership for inclusive schools: A call to action. Inclusion, 5(4), 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1352/2326-6988-5.4.234

Hutchinson, N. L., Pyle, A., Villeneuve, M., Dods, J., Dalton, C. J., & Minnes, P. (2014). Understanding parent advocacy during the transition to school of children with developmental disabilities: Three Canadian cases. Early Years: Journal of International Research and Development, 34(4), 348–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 09575146.2014.967662

Kraft-Sayre, M. E., & Pianta, R. C. (2000). Enhancing the transition to kindergarten. University of Virginia, National Center for Early Development & Learning. https://www.pakeys.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/ Enhancing-the-transition-to-kindergarten-Linking-children-families-and-schools.pdf

Levert, D. (2023). Ensuring young children have a head start: Transition practices that link early childhood education settings (Doctoral dissertation, Lehigh University). https://preserve.lib.lehigh.edu/islandora/object/ preserve%3A30970?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=294f3ab375128b3931cd&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=0

Maine Parent Federation. (2023, April 20). Transition to kindergarten [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ki6SKk45ko

Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1049732315617444

Markowitz, J., Carlson, E., Frey, W., Riley, J., Shimshak, A., Heinzen, H., Strohl, J., Lee, H., & Klein, S. (2006). Preschoolers’ characteristics, services, and results: Wave 1 overview report from the Pre-Elementary Education Longitudinal Study (PEELS). Westat. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED495723.pdf

McCrossin, J., & Lach, L. (2023). Parent-to-parent support for childhood neurodisability: A qualitative analysis and proposed model of peer support and family resilience. Child: Care, Health and Development, 49(3), 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.13069

McIntyre, L. L., Eckert, T. L., Fiese, B. H., Digennaro, F. D., & Wildenger, L. K. (2007). Transition to kindergarten: Family experiences and involvement. Early Childhood Education Journal, 35(1), 83-88. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10643-007-0175-6

McIntyre, L. L., Eckert, T. L., Fiese, B. H., DiGennaro Reed, F. D., & Wildenger, L. K. (2010). Family concerns surrounding kindergarten transition: A comparison of students in special and general education. Early Childhood Education Journal, 38(4), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-010-0416-y

Pianta, R. C., Kraft-Sayre, M., & Kraft-Sayre, M. (2003). Successful kindergarten transition: Your guide to connecting children, families & schools. Brookes.

Quintero, N., & McIntyre, L. L. (2011). Kindergarten transition preparation: A comparison of teacher and parent practices for children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Early Childhood Education Journal, 38, 411–420. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s10643-010-0427-8

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Pianta, R. C. (2000). An ecological perspective on the transition to kindergarten. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21(5), 491–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0193-3973(00)00051-4

Rossetti, Z., Burke, M. M., Rios, K., Schraml-Block, K., Rivera, J. I., Cruz, J., & Lee, J. D. (2021). From individual to systemic advocacy: Parents as change agents. Exceptionality, 29(3), 232–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 09362835.2020.1850456

Rous, B. S., & Hallam, R. (2012). Transition services for young children with disabilities: Research and future directions. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31(4), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 2F0271121411428087

Rous, B., Teeters Myers, C., & Buras Stricklin, S. (2007). Strategies for supporting transitions of young children with special needs and their families. Journal of Early Intervention, 30(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 105381510703000102

Sands, M. M., & Meadan, H. (2023). Transition to kindergarten for children with disabilities: Parent and kindergarten teacher perceptions and experiences. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/02711214221146748

Slicker, G., Barbieri, C. A., Collier, Z. K., & Hustedt, J. T. (2021). Parental involvement during the kindergarten transition and children’s early reading and mathematics skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 55, 363-376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.01.004

Starr, E. M., Martini, T. S., & Kuo, B. C. H. (2016). Transition to kindergarten for children with autism spectrum disorder: A focus group study with ethnically diverse parents, teachers, and early intervention service providers. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31(2), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1088357614532497

Stoner, J. B., Angell, M. E., House, J. J., & Bock, S. J. (2007). Transitions: Perspectives from parents of young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 19(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-007-9034-z

Waters, C. L., & Friesen, A. (2019). Parent experiences of raising a young child with multiple disabilities: The transition to preschool. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 44(1), 20-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796919826229

Welchons, L. W., & McIntyre, L. L. (2015). The transition to kindergarten for children with and without disabilities: An investigation of parent and teacher concerns and involvement. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 35(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121414523141

Appendix: Interview Questions

Background

- Tell me about your child?

- Can you describe their preschool experience?

- Can you talk about your child’s experience in kindergarten thus far?

- Classroom description

- Social aspects

- Academic aspects

- Challenges

- Highlights

Experiences of Caregivers

- How did you make decisions related to your child’s transition from preschool to kindergarten?

- Placement

- School

- IEP goals

- How would you describe your experience preparing for the transition process?

- Can you tell me about the IEP transition meeting?

- How prepared were you for the IEP transition meeting?

- How would you describe the beginning of kindergarten for you and your child?

- Can you tell me about communication with the school?

- Anything you would have done differently?

Caregiver Needs During Transition to Kindergarten

- Can you describe any challenges you experienced during the transition?

- What did you need to make more sense of the transition process?

- Can you talk about any unmet needs during this period of transition?

- How would you describe the needs of caregivers during a child’s transition from preschool to kindergarten?

Barriers and Facilitators

- Can you describe what went well during the transition?

- Please tell me about any support you received concerning your child’s transition to kindergarten.

- Can you describe the sources of support?

- How did these supports influence your advocacy during the transition?

- How would you describe the impact of these supports on your experience during the transition?

- How would you describe the impact of these supports on your child’s transition experience?

- What additional support would have been helpful?

- What advice do you have for families of preschoolers regarding the transition to kindergarten?

- Can you share your thoughts on how to improve support for caregivers during this transition?

General Follow-up Questions

Anything else you would like to share?