Caregiver Health: Having a Child with ASD and the Impact of Child Health Insurance Status

Kristin Hamre; Derek Nord; and John Andresen

Hamre, Kristin; Nord, Derek; and Andresen, John (2023) “Caregiver health: Having a child with ASD and the impact of child health insurance status,” Developmental Disabilities Network Journal: Vol. 3: Iss. 2, Article 5.

Caregiver Health: Having a Child with ASD and the Impact of Child Health Insurance Status PDF File

Plain Language Summary

This study is about parents of kids with autism (ASD). It looks at parent health and how child health insurance affects parents. Parents of kids with ASD report poorer health than parents of kids without ASD. Kids’ health insurance affects parents of kids with ASD. Parents of kids with ASD who used private insurance, public insurance, or were uninsured had poorer health. Future research and impacts on policy and practice are discussed.

Abstract

This study aims to understand the health outcomes of parents with children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and the interactive effect of child health insurance status. The study utilized 2014-2018 pooled National Health Interview Survey data to construct weighted national estimates and assess main and interaction effect logistic regression models. Findings show parents of children with ASD experienced significantly poorer health compared to parents of children without autism. Insurance status was found to significantly interact with child ASD status. Compared to parents of children without ASD who used private insurance, parents who had a child with ASD who used private insurance, public insurance, or were uninsured were found to have 1.5-, 3.2-, and 2.1-times higher odds of poorer health, respectively. Future research and implications on policy and practice are discussed.

Introduction

As the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) continues to increase, a greater number of caregivers are experiencing the varied impacts that having a child with a disability brings (Maenner et al., 2021; Myers et al., 2009). In response to the changes that a disability diagnosis brings to a family unit, caregivers often rely on a variety of formal and informal supports to maintain familial functioning, including their own health and wellbeing. While raising a child with ASD has many positive impacts on their parents (Kayfitz et al., 2010), there are also many stressors that can impact caregivers in a variety of ways (Khanna et al., 2011; McStay et al., 2014; Myers et al., 2009; Stuart & McGrew, 2009). In response to having a child with a disability, parents must adjust and adapt to maintain functional family relationships. As a result, raising a child with a disability is a complex experience for the parents that can alter the financial, social, and physical health of the caregivers (Tint & Weiss, 2016). The purpose of the present study is to extend the understanding of parenting a child with ASD as it relates to parent caregiver health and child health insurance status.

Parenting a Child With ASD: Health, Well-Being, and Functioning

Parenting a child with ASD can bring many joys to parent caregivers, and to the family unit. For example, Bayat (2007) found that families reported becoming stronger as a result of having a child with ASD in the family, with processes related to resilience, such as making a positive meaning of disability and finding a greater appreciation for life, having a strong impact (Bayat, 2007). Previous research has found that parents experience fulfillment from their caregiving role and may develop positive perspectives on life (Brouwer et al., 2005; Hoefman et al., 2014; Marks et al., 2002; Myers et al., 2009). One qualitative study found that parenting a child with ASD meant a deeper intimacy and commitment for married couples (Hock et al., 2012).

Caregiving for a child with ASD can also bring unique challenges and parents of children with ASD often experience strain related to their caregiving role (Khanna et al., 2011; Stuart & McGrew, 2009). As caregivers, parents of children with ASD experience high levels of stress, often compounded by the challenging behaviors presented by many children with ASD (Duarte et al., 2005; Hastings et al., 2005; Herring et al., 2006; Lounds et al., 2007; Lyons et al., 2010) such as difficulty adjusting to new situations, sleep problems, severe tantrums, and poorer health when compared to typically developing children (Aman, 2004; Couturier at al., 2005; Gurney et al., 2006; Kuhlthau, Orlich, et al., 2010; Kuhlthau et al., 2013; Strock, 2007). Caregiving for a child with ASD may result in elevated stress, depression, anxiety, and physical health issues among parents (Bromley et al, 2004; Hamlyn-Wright et al, 2007; Khanna et al., 2011; Kuhlthau, Kahn, et al., 2010). One longitudinal study looked at parenting children with autism over a 10-year period. In the initial research, the authors found a high level of mental health stressors and limited physical health problems, potentially attributed to stress, as well as disruption to careers. With follow up, while still experiencing stressors and, notably, an impact on careers, many parents reported improved familial experiences and relationships, noting the strong social supports in these families. Along the same lines, families who faced social rejection, as well as those where the children had more externalizing behaviors, did not experience improvement in mental health symptoms (Gray, 2002). Coping mechanisms and styles may also impact how a caregiver fares in relation to the burdens of caregiving and related stress (Lyons et al., 2010).

The existing literature offers highly heterogenous definitions of the concept of health. Much of the existing literature focuses on mental health and related conditions, an important aspect of caregiver health. In order to give a more holistic approach to understanding parent caregiver health for parents of children with ASD, Hoefman et al. (2014) utilized the care-related quality of life instrument to measure caregiver outcomes focusing on multiple domains of health, including those related to mental and physical health. The study found caregivers of children with ASD were found to experience issues such as financial problems, difficulty combining daily activities with care, experiencing depressive mood, and mental and physical health problems.

Research on mothers of grown children with ASD suggests that elevated stress and lower well-being persists compared with other parents, including those with children with other developmental disabilities (Abbeduto et al., 2004). A study exploring the impact of a psychoeducational program aimed at helping families better manage problem behaviors found programming helped to reduce family stress and improve the overall quality of the family environment (Smith et al., 2014). Positive and supportive social networks of support as well as enhancing flexibility have been found to be beneficial in reducing stress for parents of children with ASD (Begum & Mamin, 2019). It is clear that a variety of supports, including those aimed at financial relief and at bolstering personal networks, are an important resource for parent caregivers of children with ASD (Hoefman et al., 2014).

Related to the concept of caregiver health is that of family functioning. The complexities of family life and the many factors that influence the experience of the family unit resist being captured in a one-dimensional way. Many researchers have explored this topic to gain a better and more nuanced understanding of the experience of parenting, including parenting children with ASD. Much of this work is grounded in understanding parental and family adaptation and resilience (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983; Patterson, 2002; Walsh, 1996). Resilience is demonstrated by the ability for parents to go through an event and to emerge strong, or stronger, using their resources to withstand the experience (Walsh, 1998). To be clear, we do not conceptualize having a child with ASD as a storm to be weathered, or other such catastrophe, but we do acknowledge the time as a period of transition, and one that may have an impact on the parent caregiver’s overall health. Research suggests the period of time at diagnosis may be particularly stressful for parents with children with ASD, relative to other developmental disabilities (Dabrowska & Pisula, 2010; Hayes & Watson, 2013; Rezendes & Scarpa, 2011).

Research has also highlighted the importance of considering an ecological approach to understanding parental health outcomes, which includes considerations of environmental factors such as support from the extended family and the child’s schooling (Derguy et al., 2016). In addition, one study utilized Belsky’s (1984) model to look at the relationship more holistically, suggesting that both individual and environmental variables influence parental well-being, and finding that environmental resources are particularly important in managing parental stress (Belsky, 1984; Derguy et al., 2016).

Health Insurance Status and Caregiver Health

Among the constellation of supports for parent caregivers are health insurance programs they can access to support their child. These may act as a resource beyond the individual networks of support to which they have access. Private health insurance plans tend to be accessed through an employer or the broader insurance marketplace. Whereas public health insurance is accessed through government-sponsored programs. Two highly used public health insurance programs, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), provide medical insurance coverage for low-income families (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2020a, 2020c). The Medicaid program is vast, covering more than 66 million individuals in 2020 alone (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2020b), while CHIP covers many of the families who are deemed ineligible for Medicaid (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2020a). Medicaid and CHIP are federal public support programs that are administered at the state-level; therefore, each state is provided flexibility in implementation to address the needs of the local community.

The limited comparative research related to health insurance programs accessed by children with ASD has shown that experiences of those accessing private and public health insurance are not the same, resulting in differences in services and financial burden for parents. For example, Wang et al. (2013) found children with ASD receiving Medicaid accessed more services and more ASD-specific services than those utilizing private insurance. On the other hand, parents of children with ASD on private insurance experienced over five times higher odds of paying out-of-pocket insurance costs, compared to those receiving public insurance (Parish et al., 2015).

While research indicates that enrollment in public health insurance programs is associated with increased caregiver health and family quality of life (Eskow et al., 20111, 2019), further research is needed to understand the differential effects of parenting a child with ASD on parent health. Increasing the understanding about how health insurance status interacts with this parent health-child relationship is important. This study seeks to answer whether there are disparities in self-reported caregiver health between parents of children with ASD and parents with children without ASD. If present, how do ASD and child health insurance statuses interact to effect observed disparities?

Methods

Data Source and Sample

This study utilized the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) by pooling data from 2014-2018 survey years. Conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), NHIS is a nationally representative annual cross-sectional household survey. It serves as the principal source of information for studying illness, disability, and health of the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the U.S. (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016). This study utilized publicly available data, made available by the University of Minnesota’s Population Center IPUMS data system (Blewett et al., 2019).

The current NHIS sampling plan consists of 428 primary sampling units (PSUs) drawn from approximately 1,900 geographically defined PSUs that cover the 50 states and the District of Columbia. A PSU consists of a county, a contiguous group of counties, or a metropolitan statistical area (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). The CDC provides proper statistical weights for researchers to ensure the sampling procedures are accounted for in population estimation.

The multi-level structure of the NHIS data allows for investigations of children and family units by way of data integration of individual, child, and family unit data. The population of interest and the sample used in this study was U.S. householder parents of children between the ages of 4 to 17 years. Thus, the sample was restricted to only households that had a parent-child relationship or stepparent/unmarried partner-child relationship, all others were excluded, including those lacking the targeted familial relationships (e.g., grandparent or sibling) and those that did not have a sampled child in the household in the age range. After setting these criteria, the subpopulation analyzed included 43,361 parent-child family units.

Measures

The primary variables of interest included the outcome variable related to parent caregiver health and two predictors—ASD and child health insurance status. An additional 13 independent variables were included as key controls.

Fair or Poor Health

Consistent with past research using the NHIS general health self-report rating, this study employed this item as its primary outcome of interest (Alberto et al., 2020). Measuring health was done at the householder level by recoding the NHIS 5-point scale, ranging from poor to excellent. This was done by coding fair or poor health responses with “1” and coding all others as “0” (Reczek et al., 2016).

Autism Spectrum Disorder

The indication of a child’s ASD diagnosis is recorded during the NHIS survey process. Caregivers of children between the ages of 3 and 17 years of age are asked whether the sampled child had ever received a diagnosis of ASD by a doctor or other health professional. Responses were coded “1” for those with ASD and “0” for those without an ASD diagnosis.

Child Health Insurance

Responses about the sample child also include information about the kind of health insurance provided to the child. For this study, health insurance status included private insurance, public insurance, denoting use of two income-based programs, Medicaid and the Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and uninsured.

Control Variables

Thirteen control variables were included in the modeling procedures. Controlling for parent caregiver characteristics, respondent’s age and level of education entered as covariates, and education was coded from “0” (no high school diploma) to “5” (master’s degree or higher). The remaining were dummy coded and included gender (male or female), race (Asian, Black or African American, White, and other or multiple races), Hispanic ethnicity (yes or no), and insurance status of the parent.

Three variables were used to control for family-level characteristics. Family size, entered as a covariate, denoted the number of people who made up the family unit. Income-to-poverty threshold and the number of parents in the household were entered as factors.

Four variables were used to control for child characteristics. This included gender (coded as male or female), intellectual disability diagnosis (coded as yes or no), and two continuous variables (age and behavioral health). Behavioral health was measured using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 2001), which was incorporated in NHIS via an agreement between the National Center for Health Statistics and the National Institute of Mental Health. The SDQ was implemented for children who were between 4 and 17 years of age. The SDQ six-item scale includes the sum of five items that capture the degree the parents feel their child is experiencing behavioral challenges (e.g., relationships, task completion, worried, happiness, and listens to direction), by answering “not true,” “somewhat true,” and “true.” It also includes one impact item where parents gauge the severity of behaviors. The survey total score was found to highly correlate with the total score larger version of the questionnaire (0.84).

Analyses

The Stata 14 statistical program “svy” command was used for all analyses to account for the complex survey design of the NHIS survey. The IPUMS data system provides adjusted and integrated survey design variables to account for year-by-year difference in survey stratification and primary sampling unit, allowing for pooling of multiple years of data. All analyses optimized the entire NHIS dataset by way of conducting subpopulation analyses, ensuring the integrity of the full sample design was maintained while producing variance estimates (Blewett et al., 2019). Analyses conducted included bivariate estimates of the independent variables across the dependent variable. The output includes weighted percentages, standard errors, and statistical tests of independence. Weighted logistic regression was used to assess the main effects and the cross-factor interaction effects of ASD and child health insurance status on parent caregiver health.

Results

Descriptively, the weighted estimates indicate that the responding parent was predominately female (60.1%, se = 0.35) and non-Hispanic (79.6%, se = 0.51), with an average age of 42.28 (se = 0.07). Most respondents were White (77.6%, se = 0.44), followed by Black or African American (14.2%, se = 0.35), Asian (6.2%, se = 0.21), and other or multiple races (2.0%, se = 0.14). Educationally, 12.6% (se = 0.27) of respondents had no high school diploma, 21.1% (0.27) had a high school diploma, 17.7% (se = 0.25) had some college, 13.01 (se = 0.22) had an Associate’s or Vocational degree, 21.8% (se = 0.29) had a Bachelor’s degree, and 13.8% (se = 0.30) had an advanced degree such as a Master’s or Doctorate. Thirty percent of parents were uninsured (se = 0.39), whereas the majority relied on private health insurance (58.1, se = 0.44) and 11.6% (se = 0.27) relied on public health insurance.

At the family unit, 15.1% (se = 0.29) had incomes below the poverty threshold, whereas 20.8% (se = 29.3) had incomes at 1 or 1.9 time higher than the poverty threshold and 64.1% (se = 0.45) had incomes two time more or higher. The average family included 4.0 (se = 0.01) people and two parents (67.8%, se = 0.35).

The average child was male (51.5%, se = 0.29) and 10.8 (se = 0.03) years of age. A total of 2.6% (se = 0.10) had an ASD diagnosis, 1.2% (se = 0.06) had an intellectual disability, and the average Strengths and Difficulties score was 4.2 (se = 0.01). Sixty-five percent (se = 0.42) utilized private health insurance, 14.6% (se = 0.31) used public health insurance, and 20.4% (se = 0.31) were uninsured.

Table 1 summarizes the survey characteristics across the dependent variable of interest—parent self-reported health rating. All but a single variable, child’s gender, had a significant relationship to the dependent variable. Being older, female, Black/African American or other/ multiple races, Hispanic ethnicity, having lower educational attainment, and using public health insurance relate to lower health ratings. Also relating to poor health include the following family characteristics: lower income-to-poverty ratio, single parent household, and smaller and larger than average family size. Parents with children with higher behavioral health challenges, an intellectual disability, ASD, and who use public insurance also experienced lower health ratings.

| Health rating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Excellent, very good, or good (%) | Fair or poor (%) | se | Sig. |

| Parent caregiver-level | ||||

| Age (yrs) | *** | |||

| 18-29 | 92.1 | 7.9 | 0.56 | |

| 30-44 | 91.4 | 8.6 | 0.22 | |

| 45-64 | 88.4 | 11.6 | 0.33 | |

| 65 or older | 76.2 | 23.8 | 1.52 | |

| Sex | *** | |||

| Female | 88.9 | 11.2 | 0.27 | |

| Male | 91.7 | 8.3 | 0.24 | |

| Race | *** | |||

| Asian | 93.2 | 6.8 | 0.54 | |

| Black/African Amer. | 84.7 | 15.3 | 0.54 | |

| White | 90.8 | 9.2 | 0.21 | |

| Other or multiple | 84.2 | 15.8 | 1.40 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | *** | |||

| Yes | 87.6 | 12.4 | 0.43 | |

| No | 90.6 | 9.4 | 0.21 | |

| Education | *** | |||

| No HS diploma | 79.8 | 20.2 | 0.62 | |

| HS diploma | 87.0 | 13.1 | 0.43 | |

| Some college | 88.2 | 11.8 | 0.42 | |

| AA or vocational degree | 90.4 | 9.6 | 0.47 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 95.5 | 4.5 | 0.26 | |

| Advanced graduate degree | 97.0 | 3.0 | 0.26 | |

| Insurance status | *** | |||

| Private Insurance | 94.9 | 5.1 | 0.17 | |

| Public Insurance | 77.3 | 22.7 | 0.72 | |

| Uninsured | 86.1 | 13.9 | 0.36 | |

| Family-level | ||||

| Income-to-poverty ratio | *** | |||

| Below 1 | 77.0 | 23.0 | 0.63 | |

| 1-1.9 | 85.4 | 14.6 | 0.45 | |

| Over 2 | 94.6 | 5.4 | 0.17 | |

| (table continues) | ||||

| Two-parent household | *** | |||

| Yes | 92.5 | 7.5 | 0.19 | |

| No | 84.7 | 15.3 | 0.36 | |

| Family Size | *** | |||

| 2 or 3 | 88.4 | 11.7 | 0.32 | |

| 4 | 92.0 | 8.0 | 0.28 | |

| 5 or more | 89.5 | 10.5 | 0.31 | |

| Child-level | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 90.1 | 9.9 | 0.26 | |

| Male | 89.9 | 10.1 | 0.25 | |

| Strengths & Difficulties score | ||||

| Below the mean | 88.8 | 11.2 | 0.37 | |

| Mean (4) | 92.2 | 7.8 | 0.27 | |

| Greater than the mean | 88.1 | 11.9 | 0.37 | |

| Intellectual disability | *** | |||

| Yes | 79.4 | 20.6 | 2.08 | |

| No | 90.1 | 9.9 | 0.20 | |

| ASD | *** | |||

| Yes | 82.5 | 17.5 | 1.28 | |

| No | 90.2 | 9.8 | 0.20 | |

| Insurance status | *** | |||

| Private Insurance | 94.6 | 5.4 | 0.17 | |

| Public health insurance | 78.4 | 21.6 | 0.64 | |

| Uninsured | 85.5 | 14.5 | 0.46 | |

*** p ≤ .001.

Table 2 presents the weighted logistic regression results for the main and interaction effects models. The first model tests the effects of having a child with ASD on the health of parent caregivers. Holding all else equal, parents of children with ASD experienced significantly higher odds of reporting lower health outcomes (OR = 1.87, p ≤ .001). Five control variables positively related to significantly higher odds of poorer health. These included: parent age, parental health insurance status, child age, child Strengths and Difficulty score, and child health insurance status. Five control variables negatively related to poorer parental health and included Asian race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, income-to-poverty ratio, and family size.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds ratio | se | Sig. | Odds Ratio | se | Sig. |

| Parent caregiver-level | ||||||

| Age | 1.04 | 0.002 | *** | 1.04 | 0 | *** |

| Female | 1.1 | 0.060 | † | 1.1 | 0.06 | † |

| Race | ||||||

| Asian | 0.69 | 0.124 | * | 0.69 | 0.12 | * |

| Black/African Amer. | 1.1 | 0.165 | 1.1 | 0.16 | ||

| White | 0.86 | 0.121 | 0.86 | 0.12 | ||

| Other or multiple (ref.) | ||||||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.85 | 0.055 | * | 0.85 | 0.055 | * |

| Education | 0.8 | 0.013 | *** | 0.85 | 0.05 | *** |

| Insurance status | 0.8 | 0.01 | ||||

| Private Insurance (ref.) | ||||||

| Public Insurance | 1.83 | 0.224 | *** | *** | ||

| Uninsured | 1.56 | 0.134 | *** | 1.83 | 0.22 | *** |

| Family-level | 1.56 | 0.13 | ||||

| Income-to-poverty ratio | ||||||

| Below 1 (ref.) | ||||||

| 1-1.9 | 0.7 | 0.042 | *** | *** | ||

| Over 2 | 0.4 | 0.032 | *** | 0.7 | 0.04 | *** |

| Two-parent household | 0.93 | 0.051 | 0.4 | 0.03 | ||

| Family Size | 0.95 | 0.017 | ** | 0.93 | 0.05 | ** |

| Child-level | 0.95 | 0.02 | ||||

| Age | 1.02 | 0.006 | ** | ** | ||

| Female | 0.99 | 0.045 | 1.02 | 0.01 | ||

| Strengths & Difficulties score | 1.05 | 0.018 | ** | 0.99 | 0.04 | ** |

| Intellectual disability | 1.31 | 0.221 | 1.06 | 0.02 | ||

| ASD | 1.87 | 0.214 | *** | 1.28 | 0.22 | |

| Insurance status | ||||||

| Private Insurance (ref.) | (base) | |||||

| Public health insurance | 1.26 | 0.141 | * | |||

| Uninsured | 1.19 | 0.094 | * | |||

| Insurance status by ASD interaction | ||||||

| Private insurance – no ASD (ref.) | ||||||

| Private insurance – ASD | 1.54 | 0.29 | * | |||

| Public insurance – no ASD | 1.24 | 0.14 | † | |||

| Public insurance – ASD | 3.19 | 0.72 | *** | |||

| Uninsured – no ASD | 1.19 | 0.09 | * | |||

| Uninsured – ASD | 2.05 | 0.47 | ** | |||

| Constant | 0.04 | 0.009 | *** | 0.04 | 0.01 | *** |

*, p < .05; **, p ≤ .01; ***, p ≤ .001; †, p < .10.

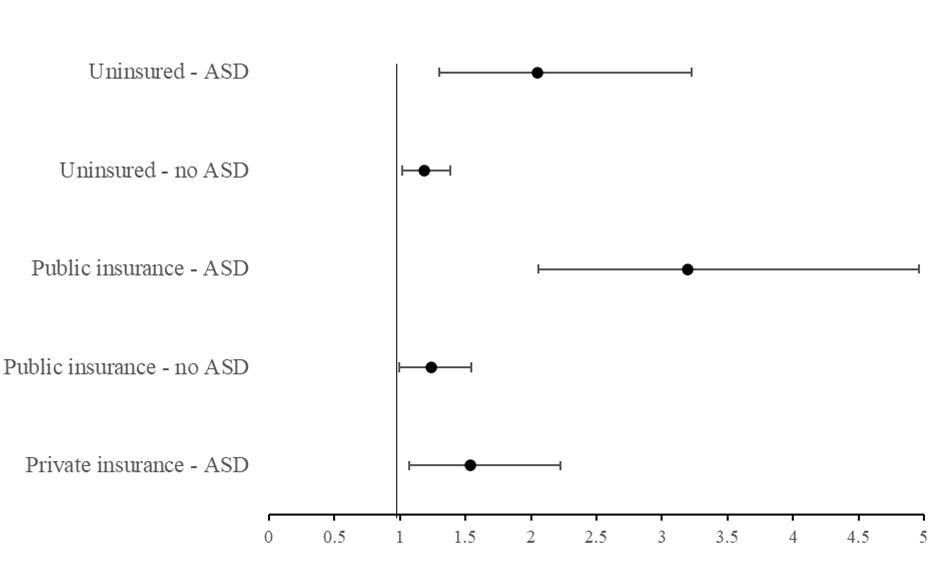

Model two incorporated a two-factor interaction to account for the differential effects of having a child with ASD who has private or public health insurance or is uninsured. Compared to the reference group, parents of children without ASD who use private insurance, four of the five comparison groups experienced significantly higher odds of poor health. Parents of children with ASD experienced the highest odds and include 3.19 for those using public insurance (p ≤ .001), 2.05 for those uninsured (p ≤ .01), and 1.54 for those using private insurance (p ≤ .05). Parents of children without ASD who were uninsured experienced 1.19 higher odds of poorer health (p ≤ .05). Figure 1 presents a forest plot of the interaction term that depicts the odds ratio point estimates and 99% confidence intervals.

Note. The prediction model holds the following constant: adult age (42.3 years), female, White, Not Hispanic, H.S. diploma, out of the labor force, below the poverty threshold, multiple parents, family size (4.0), child age (10.8 years), and Strengths and Difficulties score (4.2).

Note. The prediction model holds the following constant: adult age (42.3 years), female, White, Not Hispanic, H.S. diploma, out of the labor force, below the poverty threshold, multiple parents, family size (4.0), child age (10.8 years), and Strengths and Difficulties score (4.2).Discussion

This research investigated whether disparities exist between the health of parent-caregivers who had children with ASD and parent caregivers who had children without ASD. Holding all else constant, we found that parent caregivers of children with ASD are nearly two times more likely to report worse health statuses than their peers who had children without ASD. As we seek to understand the effects of family dynamics among parents of children with ASD, this finding is particularly important. Situated in the broader literature, this finding is consistent with past research of parent caregivers that found parents of children with disabilities experienced greater disparities. Where past research focused predominately on the stress and mental health of caregivers and their coping (Bromley et al, 2004; Duarte et al., 2005; Hamlyn-Wright et al., 2007; Khanna et al., 2011; Lyons et al., 2010) or utilized limited sample sizes (Hoefman et al., 2014), this study expands this line by drawing attention to self-reported health outcomes by way of a large, nationally representative dataset. While this research is not causal, and the results should not be interpreted as such, it does highlight an important relationship between being a parent caregiver to a child with ASD as it relates to parent health outcomes.

Advancing this research further, this study sought to understand how child health insurance status affected the relationship between parent health and having a child with ASD. Specifically, we sought to test whether parent health disparities hold or are exacerbated across different child health insurance statuses by providing a more granular inspection of how parents of children with ASD fare compared to those without children with ASD who use private insurance. Findings showed that child insurance status does, in fact, significantly interact with the effects of child ASD status on parent self-reported health. Compared to the reference group, those who had children with ASD who had private insurance experienced 1.54 times higher odds of poorer health (p ≤ .05, small effect); those with public health insurance and children with ASD experienced 3.19 times higher odds of poorer health (p ≤ .001, medium effect); and those with uninsured children with ASD experienced 2.05 times higher odds of poorer health (p ≤ .01, small effect).

The results indicate challenges experienced by parents of children with ASD generally, and challenges of children with ASD who utilize public health insurance programs more specifically. This has direct implications for policy and practice. For practitioners, particularly those serving a child with ASD, it is important to think about the challenges experienced by the parent caregiver and the impact that has on the functioning of the family and the child. When practicing with a child, we must approach the child consistently with an ecological approach to practice and an understanding of the family as an interconnected unit and a resource. If a child’s caregiver is experiencing poor health, we must understand that may impact the child and the ability for that child’s developmental and health needs to be met. Similarly, for policymakers, and stakeholders involved in the policy process, embracing policies that are more family-centric rather than those that are individual child-centric may add supports and needed services to the primary caregiver, therefore helping the child in a way that may be more sustainable, long-lasting, and impactful.

Past research has indicated that children from under-represented communities are diagnosed with ASD later than White children (Constantino et al., 2020). Mandell et al. (2007) found that Black children were 5.1 times more likely to be misdiagnosed with a conduct disorder prior to being diagnosed with ASD. Further, it is known that early intervention services are important both for immediate and long-term outcomes for children with ASD. It stands to reason that getting a diagnosis later, as well as being misdiagnosed with something such as a conduct disorder (itself stigmatized) may increase the stress and negative outcomes related to caregivers’ own health. Magaña and Smith (2006) examined emotional well-being for mothers co-residing with children or adults with ASD, comparing Latina mothers and White mothers, their qualitative analysis finding that both sets of mothers valued the family cohesion with Latina mothers less likely to report on negative aspects of co-residing. Future research should explore health disparities for caregivers of children with ASD who are from historically marginalized communities to understand the impact of the myriad and complex issues contributing to the health of the caregiver.

It is also important to recognize that the health of the family and the health of the family members are inextricably linked. The links between stress and health are well established. Public health insurance programs aimed at providing health coverage for low-income families may provide an opportunity to intervene to support caregivers. Interventions that address well-being beyond the individual, including programs and policies, help people experiencing sustained stress in their family life (Thoits, 2010). It is important to consider the costs incurred by families with children with disabilities, which may include specialized therapies and diets, technology and equipment, and other supports. Such costs may contribute to a family’s participation in public health insurance programs. While the supports provide access to medical care, they may not fully account for a family’s experience, resulting in gaps that contribute to decreased health among caregivers.

This study has shown that poorer health outcomes are experienced by caregivers of children with ASD in general, and those with children accessing public health insurance or who are uninsured with greater effects. It is important to acknowledge that poverty is an issue that impacts people with disabilities disproportionately and is associated with a number of poorer outcomes across domains, including health outcomes. In seeking to help families who have children with ASD, it is important that interventions consider the impacts and opportunities to support caregiver health. Studies have highlighted that decreasing the impact of caregiving burdens can decrease caregiver exhaustion, increasing overall physical health. Parents report that maintaining healthy, effective support systems around their family can improve the lives of the entire family (Kuhlthau et al., 2014). For example, Tilford et al. (2015) found that treatments that improve sleep for children with ASD can improve the physical health of caregivers. Similarly, both greater financial health and fewer children are shown to be related to greater physical health of caregivers of children with ASD (Lee et al., 2009). While these types of supports are valuable to caregivers, there are also larger state systems that can provide additional care and support.

Additionally, it is known that poor health relates to other life outcomes that can put further strain on parents. Future research is needed to understand how the health of parents of children with ASD interplays with other life domains, such as employment and educational attainment. Understanding the extent to which public health insurance programs contribute to experienced outcomes is also beneficial. Further, given the evidence around the known impact of early intervention and stressors around time of diagnosis, future research should focus on data collection that would allow for robust longitudinal studies, which may be able to increase understanding of caregiver health as impacted by age of child at diagnosis as well as issues across the lifespan.

Limitations

This research has a number of limitations. First, though the study was able to account for important variables about the parent, such as health insurance status, other variables were absent, such as disability status; thus, excluding potential important factors that may relate to health outcomes in the model. Additionally, the NHIS asks respondents to rate their general health, the construct of which may be interpreted differently by individual respondents. The NHIS data do not allow for specificity within the construct of health. Further, the NHIS has the inherent limitations of self-reported data. For example, some respondents may have evaluated their health at that moment they were asked to respond, and others may have given a response based on a general assessment of their ongoing overall health. The use of cross-sectional data does not allow for establishing causality. Additionally, the NHIS omits institutionalized individuals, thus missing such segments of the population as military personnel or people in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities.

Conclusion

The experience of parenting is a complex concept, one that resists being defined and reduced to a wholly negative of wholly positive experience, with many “highs” and joys, and of course challenges and “lows.” Even during challenges, a family may recollect or experience an event in a positive way because of the strength of the parents and of the family unit as a whole. Caregiver health is an important part of a family’s overall health and functioning and is of particular concern for parents and families who have children with ASD. Programs such as Medicaid and CHIP provide formal support to caregivers of children with ASD; however, this is not enough to promote the overall health of the caregivers. In seeking to support families, interventions must consider support for the family in a holistic way. By implementing family-level interventions in programmatic and policy interventions, we are extending beyond the limited view of simply “treating” the child’s condition. Instead, we can meet the parents where they are at and provide supports at the parent and family level, supporting that system to function well, and, therefore, providing a robust system of support for the child with ASD to thrive and grow as valued members of their families and their communities.

References

Abbeduto, L., Seltzer, M. M., Shattuck, P., Krauss, M. W., Orsmond, G., & Murphy, M. M. (2004). Psychological well-being and coping in mothers of youths with autism, down syndrome, or fragile x syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 109(3), 237-254. https://doi.org/10.1352/ 0895-8017(2004)109<237:PWACIM>2.0.CO;2

Alberto, C. K., Pintor, J. K., Langellier, B., Tabb, L. P., Martínez-Donate, A. P., & Stimpson, J. P. (2020). Association of maternal characteristics with Latino youth health insurance disparities in the United States: a generalized structural equation modeling approach. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09188-1

Aman, M. G. (2004). Management of hyperactivity and other acting-out problems in patients with autism spectrum disorder. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology, 11(3), 225–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.spen.2004.07.006

Bayat, M. (2007). Evidence of resilience in families of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51(9), 702-714. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00960.x

Begum, R., & Mamin, F. A. (2019). Impact of autism spectrum disorder on family. Autism-Open Access, 9(4), 1-6. https://www.autismnetworks.org/abstract/auo/impact-of-autism-spectrum-disorder-on-family-44919.html

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83-96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129836

Blewett, L., Drew, J., King, M., & Williams, K. (2019). IPUMS Health Surveys: National Health Interview Survey, Version 6.4 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. https://doi.org/10.18128/D070.V6.4

Bromley, J., Hare, D. J., Davison, K., & Emerson, E. (2004). Mothers supporting children with autistic spectrum disorders: Social support, mental health status and satisfaction with services. Autism, 8(4), 409-423. Doi: 10.1177/1362361304047224

Brouwer, W. B., Van Exel, N. J., Van den Berg, B., Van den Bos, G. A., & Koopmanschap, M. A. (2005). Process utility from providing informal care: The benefit of caring. Health Policy, 74(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.12.008

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). 2014 National Health Interview Survey public use data release. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2014/ srvydesc.pdf

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020a). The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). https://www.healthcare.gov/medicaid-chip/childrens-health-insurance-program/

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020b). May 2020 Medicaid and CHIP enrollment data highlights. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enroll ment-data/report-highlights/index.html

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020c). Program history. https://www.medicaid.gov/about-us/program-history/index.html#:~:text=Authorized%20by%20Title%20XIX%20of,coverage%20 for%20low%2Dincome%20people

Constantino, J. N., Abbacchi, A. M., Saulnier, C., Klaiman, C., Mandell, D. S., Zhang, Y., Hawks, Z., Bates, J., Klin, A., Shattuck, P., Molholm, S., Fitzgerald, R., Roux, A., Lowe, J. K., Geschwind, D. H. (2020). Timing of the diagnosis of autism in African American children. Pediatrics, 146(3), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3629

Couturier, J. L., Speechley, K. N., Steele, M., Norman, R., Stringer, B., & Nicolson, R. (2005). Parental perception of sleep problems in children of normal intelligence with pervasive developmental disorders: Prevalence, severity, and pattern. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(8), 815–822. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000166377.22651.87

Dabrowska, A., & Pisula, E. (2010). Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre‐school children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(3), 266-280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01258.x

Derguy, C., M’bailara, K., Michel, G., Roux, S., & Bouvard, M. (2016). The need for an ecological approach to parental stress in autism spectrum disorders: The combined role of individual and environmental factors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(6), 1895-1905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2719-3

Duarte, C. S., Bordin, I. A., Yazigi, L., & Mooney, J. (2005). Factors associated with stress in mothers of children with autism. Autism, 9, 416–427. doi: 10.1177/1362361305056081

Eskow, K., Chasson, G. S., & Summers, J. A. (2019). The role of choice and control in the impact of autism waiver services on family quality of life and child progress. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(5), 2035-2048. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-03886-5

Eskow, K., Pineles, L., & Summers, J. A. (2011). Exploring the effect of autism waiver services on family outcomes. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 8(1), 28-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2011.00284.x

Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337-1345. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015

Gray, D. E. (2002). Ten years on: A longitudinal study of families of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 27(3), 215-222. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 1366825021000008639

Gurney, J. G., McPheeters, M. L., & Davis, M. M. (2006). Parental report of health conditions and health care use among children with and without autism: National Survey of Children’s Health. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160(8), 825-830. doi:10.1001/archpedi.160.8.825

Hamlyn-Wright, S., Draghi-Lorenz, R., & Ellis, J. (2007). Locus of control fails to mediate between stress and anxiety and depression in parents of children with a developmental disorder. Autism, 11(6), 489–501. doi: 10.1177/1362361307083258

Hastings, R. P., Kovshoff, H., Brown, T., Ward, N. J., Espinosa, F. D., & Remington, B. (2005). Coping strategies in mothers and fathers of preschool and school-age children with autism. Autism, 9(4), 377-391. doi: 10.1177/1362361305056078

Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 629-642. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y

Herring, S., Gray, K., Taffe, J., Tonge, B., Sweeney, D., & Einfeld, S. (2006). Behaviour and emotional problems in toddlers with pervasive developmental disorders and developmental delay: Associations with parental mental health and family functioning. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(12), 874-882. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00904.x

Hock, R. M., Timm, T. M., & Ramisch, J. L. (2012). Parenting children with autism spectrum disorders: A crucible for couple relationships. Child & Family Social Work, 17(4), 406-415. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2011.00794.x

Hoefman, R., Payakachat, N., van Exel, J., Kuhlthau, K., Kovacs, E., Pyne, J., & Tilford, J. M. (2014). Caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder and parents’ quality of life: Application of the CarerQol. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(8), 1933-1945. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 10803-014-2066-1

Kayfitz, A. D., Gragg, M. N., & Orr, R. R. (2010). Positive experiences of mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23(4), 337-343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00539.x

Khanna, R., Madhavan, S. S., Smith, M. J., Patrick, J. H., Tworek, C., & Becker-Cottrill, B. (2011). Assessment of health-related quality of life among primary caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(9), 1214–1227. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10803-010-1140-6

Kuhlthau, K., Kahn, R., Hill, K. S., Gnanasekaran, S., & Ettner, S. L. (2010). The well-being of parental caregivers of children with activity limitations. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0434-1

Kuhlthau, K., Orlich, F., Hall, T. A., Sikora, D., Kovacs, E. A., Delahaye, J. & Clemons, T. E. (2010). Health-related quality of life in children with autism spectrum disorders: Results from the autism treatment network. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(6), 721–729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0921-2

Kuhlthau, K., Kovacs, E. A., Hall, T., Clemmons, T., Orlich, F., Delahaye, J., & Sikora, D. (2013). Health-related quality of life for children with ASD: Associations with behavioral characteristics. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(9), 1035–1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.04.006

Kuhlthau, K., Payakachat, N., Delahaye, J., Hurson, J., Pyne, J. M., Kovacs, E., & Tilford, J. M. (2014). Quality of life for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(10), 1339-1350. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2014.07.002

Lee, G. K., Lopata, C., Volker, M. A., Thomeer, M. L., Nida, R. E., Toomey, J. A., Chow, S., Smerbeck, A. M. (2009). Health-Related Quality of Life of Parents of Children With High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(4), 227-239. doi:10.1177/1088357609347371

Lounds, J., Seltzer, M. M., Greenberg, J. S., & Shattuck, P. T. (2007). Transition and change in adolescents and young adults with autism: Longitudinal effects on maternal well-being. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 112(6), 401-417. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[401:TACIAA] 2.0.CO;2

Lyons, A. M., Leon, S. C., Roecker Phelps, C. E., & Dunleavy, A. M. (2010). The impact of child symptom severity on stress among parents of children with ASD: The moderating role of coping styles. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(4), 516-524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9323-5

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Esler, A., Furnier, S. M., Hallas, L., Hall-Lande, J., Hudson, A. Hughes, M. M., Patrick, M., Pierce, K., Poynter, J., Salinas, A., Shenouda, J., Vehorn, A., Warren, Z., Constantino, J. N., … Cogswell, M. E. (2021). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 70(11), 1-16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1

Magaña, S., & Smith, M. J. (2006). Psychological distress and well–being of Latina and non–Latina white mothers of youth and adults with an autism spectrum disorder: Cultural attitudes towards coresidence status. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(3), 346-357. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.346

Mandell, D. S., Ittenbach, R. F., Levy, S. E., & Pinto-Martin, J. A. (2007). Disparities in diagnoses received prior to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(9), 1795-1802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0314-8

Marks, N. F., Lambert, J. D., & Choi, H. (2002). Transitions to caregiving, gender, and psychological well‐being: A prospective US national study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(3), 657-667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00657.x

McCubbin, H. I., & Patterson, J. M. (1983). The family stress process: The double ABCX model of adjustment and adaptation. Marriage & Family Review, 6(1-2), 7-37. https://doi.org/10.1300/ J002v06n01_02

McStay, R. L., Trembath, D., & Dissanayake, C. (2014). Stress and family quality of life in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: Parent gender and the double ABCX model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3101-3118. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2178-7

Myers, B. J., Mackintosh, V. H., & Goin-Kochel, R. P. (2009). “My greatest joy and my greatest heart ache:” Parents’ own words on how having a child in the autism spectrum has affected their lives and their families’ lives. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(3), 670-684. doi:10.1016/ j.rasd.2009.01.004

National Center for Health Statistics. (2016). About the National Health Interview Survey. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm

Parish, S. L., Thomas, K. C., Williams, C. S., & Crossman, M. K. (2015). Autism and families’ financial burden: the association with health insurance coverage. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 120(2), 166-175. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-120.2.166

Patterson, J. M. (2002). Understanding family resilience. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(3), 233-246. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10019

Reczek, C., Spiker, R., Liu, H., & Crosnoe, R. (2016). Family structure and child health: Does the sex composition of parents matter? Demography, 53(5), 1605-1630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0501-y

Rezendes, D. L., & Scarpa, A. (2011). Associations between parental anxiety/depression and child behavior problems related to autism spectrum disorders: The roles of parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy. Autism Research and Treatment, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/395190

Smith, L. E., Greenberg, J. S., & Mailick, M. R. (2014). The family context of autism spectrum disorders: Influence on the behavioral phenotype and quality of life. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 23(1), 143-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2013.08.006

Strock, M. (2007). Autism spectrum disorders (pervasive developmental disorders). Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED495219

Stuart, M., & McGrew, J. H. (2009). Caregiver burden after receiving a diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(1), 86-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd. 2008.04.006

Thoits, P. A. (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1_suppl), S41-S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499

Tilford, J. M., Payakachat, N., Kuhlthau, K. A., Pyne, J. M., Kovacs, E., Bellando, J., Williams, D. K., Brouwer, W., Frye, R. E. (2015). Treatment for sleep problems in children with autism and caregiver spillover effects. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(11), 3613-3623. doi:10.1007/s10803-015-2507-5

Tint, A., & Weiss, J. A. (2016). Family wellbeing of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Autism, 20(3), 262-275. doi:10.1177/1362361315580442

Walsh, F. (1996). The concept of family resilience: Crisis and challenge. Family Process, 35(3), 261-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1996.00261.x

Wang, L., Mandell, D. S., Lawer, L., Cidav, Z., & Leslie, D. L. (2013). Healthcare service use and costs for autism spectrum disorder: a comparison between Medicaid and private insurance. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(5), 1057-1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1649-y