6 The Promising Practice of Cultural Brokering Support with Culturally Diverse Families of Children with Developmental Disabilities: Perspectives From Families

Yali Pang and Dana V. Yarbrough

Pang, Yali and Yarbrough, Dana V. (2023) “The promising practice of cultural brokering support with culturally diverse families of children with developmental disabilities: Perspectives from families,” Developmental Disabilities Network Journal: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 7.

Plain Language Summary

In this article, we write about parents of children with developmental disabilities (DD) who work as cultural brokers. To learn more about the role of a cultural broker, we talked to 30 diverse families who received Parent to Parent support from a cultural broker. We learned that cultural brokers are listeners, teachers, connectors, and go-betweens. In addition, we found that help from another parent from a similar culture helped families understand disability systems, be an advocate for their child, and have hope for their child’s future.

Abstract

Background and Purpose:

The Parent to parent model of support has been found to be effective with supporting families of children with DD in navigating complex systems, gaining emotional support, building positive resilience, sharing ideas, and learning problem solving skills. Parent to Parent ties can be particularly strong when cultural capital is involved. This study presents a cultural brokering initiative embedded in the evidence-informed Parent to Parent support model that could be a promising practice to support culturally diverse families of children with DD.

Methods:

This study used a mixed methods approach to examine the practice and outcomes of a cultural brokering initiative in a statewide Parent to Parent support program in a University Center of Excellence in Developmental Disabilities that serves culturally diverse families of children with DD. Both surveys and interviews were used to learn about these families’ experiences with cultural brokering services and their perspectives on the effectiveness of these services in meeting their families’ needs.

Results:

The findings of this study show that cultural brokers primarily serve in the roles of listeners, interpreters, educators, liaisons, and mediators when supporting culturally diverse families of children with DD, and that parents overall had a high rating of the cultural brokering service and were very satisfied with the support they received.

Implications:

A cultural brokering initiative embedded in the Parent to parent support model is a promising practice that could better support culturally diverse families of children with DD and improve the service outcomes to these families. However, service providers who want to start a cultural brokering initiative should work closely with families to decide the roles of a cultural broker, how they will offer support, and who should be a cultural broker to represent and support a particular community.

Introduction

A vast amount of research has documented the unique challenges experienced by families of children with developmental disabilities (DD) (e.g., Hayes & Watson, 2013; Lindsay et al., 2012; Woodgate et al., 2008; Woodman et al. 2015). Research indicated that parents of children with DD often carry out greater child-raising responsibilities (Anderson, 2009), and experience increased psychological stress, anxiety, isolation, and other difficulties compared to parents of typically developing children (Dodds & Walch, 2022; Woodman et al., 2015). Parents frequently reported that ineffective communication with service providers, disconnection between services, lack of knowledge, inexperience with the disability service systems, and overwhelming application procedures are some of the main barriers in accessing and receiving disability services and resources (Anderson, 2009; Freedman & Boyer, 2000; Garwick et al., 1998). This is particularly true for culturally diverse families of children with DD who often face additional challenges because of language barriers, cultural conflicts, divergent beliefs, social stigma, and financial instability, resulting in worsening health concerns and poor service outcomes (Brandon & Brown, 2009; Ishimaru et al., 2016; Mirza & Heinemann, 2012). Culturally diverse families in this research refer to families from minority communities, such as communities of color, immigrants, and/or refugees, whose culture is not dominant in the country where they are living and seeking for services and resources (Pang et al., 2020). Literature finds that service providers often misunderstand the culture and resources of culturally diverse families and are inadequate in building trust with, and responding to, the needs of these families (Lewis & Diamond, 2015; Mirza & Heinemann, 2012). In addition, culturally diverse parents are often not clear about their rights and roles and can be found discouraged and disengaged during the service process, which makes it difficult for them to effectively use the service systems (Dyrness, 2011; Ishimaru et al., 2016; Szente et al., 2006).

Parent to Parent support is a systematic approach in which experienced, trained parents of children with disabilities are matched with newly referred parents of children with disabilities who are just starting to understand the needs they have related to their child (Santelli et al., 1997). Over the past several decades, the Parent to Parent model of support has been found to be effective with supporting families of children with disabilities in navigating complex systems, gaining emotional support, building positive resilience, sharing ideas, and learning problem-solving skills (Bray et al., 2017; Solomon et al., 2001; Winch & Christoph, 1988). In addition, Parent to Parent ties can be particularly strong when cultural capital is involved, as families can share information that is grounded in common language and culturally bound understandings of disability and family roles (Dodds et al., 2018; Pang et al., 2020). Research suggests that family support services that acknowledge cultural difference, intersecting identities, and divergent needs can better meet the needs, and promote the health and wellbeing, of children with DD and their families, especially those from minority communities (Achola & Greene, 2016; Bray et al., 2017; Holloway et al., 2018).

Cultural brokering in this study is a culturally responsive support, grounded in the Parent to Parent evidenced-informed support model, for culturally diverse families of children with DD. Cultural brokering is defined as “the act of bridging, linking or mediating between groups or persons of differing cultural systems for the purpose of reducing conflict or producing change” (Jezewski, 1995, p. 20). It has been increasingly recognized as a promising approach in helping culturally diverse families navigate healthcare, education, disability and other social services, facilitating communication and collaboration between families and service providers, and improving families’ capacity for meeting challenges (Pang et al., 2019; Rotich & Kaya 2014; Yohani, 2013). While prior research has recognized the value of cultural brokering services and/or Parent to Parent support to culturally diverse families (e.g., Cooper et al., 1999; Dodds et al., 2018; Ishimaru et al., 2016; Jezewski & Sotnik, 2005; McCabe, 2008), little evidence is available on the effectiveness of using cultural brokers in Parent to Parent emotional, informational, and systems navigational support to families of children with DD, especially from the perspectives of families (Dodds & Walch, 2022; Mueller et al., 2009; Pang et al., 2020). To fill this research gap, this study used a mixed-methods approach with a statewide Parent to Parent cultural brokering program to explore the experiences of culturally diverse families and the effectiveness of these services in meeting the needs of these families and their children with DD.

Theoretical Framework

The cultural brokering initiative in this study was a family support model that was embedded in a statewide Parent to Parent support program housed in a University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCEDD; Pang et al., 2019). In the Parent to Parent support model, parents are matched based on having children with the same or similar special needs, while other components such as age and location may sometimes be considered based on the needs of the referred parents (Brookman, 1988; Santelli et al., 1997). This model proposes that experienced parents are valuable emotional support to newly referred parents by sharing their experiences, offering practical information, helping them access support networks, and just being supportive listeners (Brookman, 1988; Mueller et al., 2009). The cultural brokering model, adapted to the disability field from the healthcare industry, partners cultural brokers with culturally diverse parents of children with DD to address conflicts and problems that parents experience in navigating and utilizing disability services (Jezewski & Sotnik, 2005). Cultural brokers are usually members from the same racial, ethnic community as the families seeking support, and they are knowledgeable about the DD service systems (Jezewski & Sotnik, 2005). This cultural brokering model not only recognizes disability as an important identity of culturally diverse families, but also identifies other intersecting identities of families including, but not limited to, age, cultural background, culture sensitivity, language, stigma. and power (Jezewski & Sotnik, 2005).

The cultural brokering initiative of this study is built on the intersection of both the Parent to Parent model and the cultural brokering model. In this initiative, experienced parents of children with DD are recruited and trained as cultural brokers and then matched with newly referred parents of children with DD based on disability, culture, language, and age, for example, to provide “enhanced one-to-one enhanced emotional, informational, and systems navigational support to racially, ethnically, and/or linguistically diverse families of children with DD” (Pang et al., 2019, p. 130). This initiative values the practical knowledge and experiences of parents who have been living with and raising a child with similar disabilities, and also recognizes the interplay of intersectional identities of newly referred families and the potential impacts of these components on families’ access to and utilization of disability and other services, which improves the effectiveness of, and equity in, service delivery and outcomes to these families.

Program Overview

The cultural brokering initiative of this study was established with state funding in 2009 in the UCEDD’s statewide Parent to Parent support program to better identify the difficulties and barriers experienced by culturally diverse families in understanding and accessing disability services and resources. The original staff of this program included a director and two part-time staff working as cultural brokers with Latino/a/x and Black/African American families. Since 2009, the program staffing has ebbed and flowed between four and seven cultural brokers. Currently, the program is both federally and state funded and includes a director and four cultural brokers who work between 14 and 20 hours per week representing Black/African American, Latino/a/x, Asian, Arabic and refugee communities.

Newly recruited cultural brokers participate in a 12-hour training that covers topics such as program orientation, active listening and communication skills, sharing family stories, role playing scenarios, the adjustment/adaptation process, cultural agility, state and community resources, building hope/positive resiliency, and data collection and confidentiality that are required of all staff and volunteers of this statewide Parent to Parent support program. Upon completion of the training, cultural brokers are matched with families referred to or reaching out individually to the UCEDD’s Parent to Parent program for support. The enhanced emotional, informational and systems navigational support provided by the cultural brokers in this study typically occur via telephone, but the Parent to Parent support program also operates support groups for Latino/a/x and Arabic speaking families of children with DD.

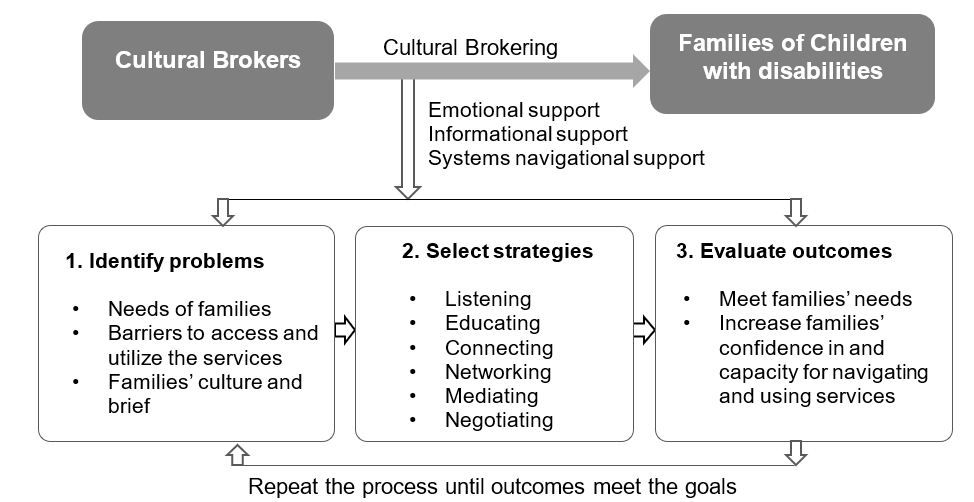

Figure 1 describes the three typical stages in the cultural brokering process. Generally, after being matched with a parent with a child with DD, cultural brokers contact the parent and learn about the family’s issues and needs while also considering the family’s culture and beliefs, which is the first stage of the cultural brokering process. At the second stage, cultural brokers select appropriate strategies to help the family to address their problems and get their needs met. At the final stage, cultural brokers assess whether their emotional, informational, and systems navigational support has been successful in meeting this family’s needs and increases their confidence in and capacity for navigating systems on their own. If families’ needs are not met at the final stage, cultural brokers will repeat the process until families’ report that needs are met, or their current issues are resolved.

Note. Cultural brokering process in the Parent to Parent support program. Adapted from cultural brokering intervention for families of children receiving special education (p. 132), by Y. Pang et al. (2019). Copyright 2019 by Springer Nature. Adapted with permission.

Study Purpose

The purpose of this study was to validate the intersection of Parent to Parent support and cultural brokering through the experiences and perspectives of culturally diverse families of children with DD (i.e., how the support built family resilience and helped families navigate service systems to meet families’ needs). Specifically, this study addressed the following research questions.

- What kind of support have culturally diverse families received from cultural brokers?

- How effective are cultural brokers in meeting the needs of families?

A better evidence base for Parent to Parent support through cultural brokers would contribute to the development of more effective family support programs and help service providers use cultural brokers to better respond to the needs of culturally diverse families of children with DD.

Methods

Research Design

This study used a mixed methods approach combining both surveys and interviews to culturally diverse parents who had been working with cultural brokers in the statewide Parent to Parent support program. Mixed methods research is “the type of research in which a researcher or team of researchers combines elements of qualitative and quantitative research approaches for the purpose of breadth and depth of understanding and corroboration” (Johnson et al., 2007, p. 123). Mixed methods research design is considered as a compelling approach for evaluating programs (Burch & Heinrich, 2015). It is helpful in answering what and how/why questions and can offer a more in-depth and comprehensive understanding of the phenomena (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The design of the survey and interview was based on the cultural brokering literature (Jezewski, 1995; Jezewski & Sotnik, 2005) and the findings about the roles, procedures, and components for an effective cultural brokering intervention in our prior studies (Pang et al., 2019, 2020). Both the survey and interviews used similar criteria including the roles of cultural brokers, communications with cultural brokers, experiences with cultural brokers, preferences of having a cultural broker, and the effectiveness and challenges of working with cultural brokers to learn about families’ perspectives regarding their cultural brokering services. The survey and interviews were carried out independently between 2019 and 2021 in the Eastern U.S., the state where the Parent to Parent support program is located. In addition, the research design received approval from the sponsoring university’s Institutional Review Board.

Sample

Culturally diverse parents of children with DD were the target population of this study. The participants were selected based on a purposive sampling strategy. The inclusion criteria for participants in both the survey and interview included being a parent who had at least one child with DD, who came from a culturally diverse family, and who had worked with or was currently working with cultural brokers in the statewide Parent to Parent support program. Eligible parents for the survey and interview were recruited by disseminating fliers through cultural brokers who worked or were currently working with these parents as well as the program’s social media page (e.g., Facebook). The survey included filter questions to check the eligibility of the participants. Only eligible participants were directed to the remaining survey questions. Both the survey and fliers were offered in three languages (i.e., English, Spanish, and Arabic) as suggested by cultural brokers to cover most of the languages spoken by the parents receiving services from the Parent to Parent support program. For interviews, bilingual staff assisted with scheduling the interviews with the primary researcher if the parents spoke a language other than English. In addition, the UCEDD’s Parent to Parent support program’s contract with Language Line Services assisted with interpreting with parents who preferred a language other than English during interviews.

Data Collection and Analysis

The primary data source for this study was quantitative data from the survey and qualitative data from both the survey and interviews. The survey data were collected online to learn about families’ experience and perspectives of working with cultural brokers and areas for cultural brokers to improve their services. The survey included both close- and open-ended questions. The semistructured interviews were conducted by telephone after the survey (an average of 30-40 minutes) to learn more about families’ experience working with cultural brokers. The quantitative data from the survey were analyzed using descriptive analysis in Excel and SPSS, and the qualitative data from both the survey and interviews were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis in Dedoose with both inductive and deductive coding to generate main themes.

Results

Before presenting our findings, through self-reflection, we acknowledged our standpoints as educated Asian and Caucasian women. One of us shares the lived experiences of the study participants as she is herself a parent of a child with intellectual and developmental disabilities who highly values Parent to Parent support. We are both intrigued by the intersectionality of cultural and social identities and the barriers that block access to critical services and supports for culturally and linguistically diverse children with disabilities and their families. Therefore, we acknowledge our positionality both professionally and personally.

Participants Descriptions

For the survey, there were a total of 37 responses with 7 invalid responses. Of the 30 valid responses (see Table 1), most participants (60%) identified their preferred language as Spanish and about 86.7% of the participants were mother. For the age, about 33.3% of the participants were between 30 and 39, followed by those aged between 40 and 49 (23.3%) and those aged between 50 and 59 (16.7%). Only one participant was between 18 and 29. Most participants (60.0%) identified themselves as Hispanic/Latino; and 23.3% of the participants identified themselves as Black followed by White (13.3%). No participants identified themselves as Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, or Bi-racial. Also, about 40% reported having a bachelor’s degree or associate degree. However, most of the participants were at a low household income level. About 33.3% participants reported a household income below $25,000, and 23.3% (n = 7) between $25,000 and $49,999. None of the participants reported a household income of $100,000 and above. About the family member with DD, most of the survey participants (73.3%, n = 22) reported their child with DD was less than 18 years old; and most of the children/adults with DD (70.0%) had autism (70%, n = 21).

| Variables | Subcategories | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Preferred language | English | 23.3 |

| Spanish | 60.0 | |

| Arabic | 16.7 | |

| Role | Mother | 86.7 |

| Father | 6.7 | |

| Missing data | 6.7 | |

| Age | 18-29 | 3.3 |

| 30-39 | 33.3 | |

| 40-49 | 23.3 | |

| 50-59 | 16.7 | |

| Missing data | 23.3 | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 13.3 |

| Black | 23.3 | |

| Missing data | 13.3 | |

| Hispanic/Latinx (Yes) | 60.0 | |

| Education level | Less than high school | 6.7 |

| High school or the equivalent | 26.7 | |

| Some college credit without degree | 10.0 | |

| Bachelor’s or associate degree | 40.0 | |

| Some postgraduate work but no degree | 3.3 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 6.7 | |

| Missing data | 6.7 | |

| Income level | Below $25,000 | 33.3 |

| $25,000 – $49,999 | 23.3 | |

| $50,000 – $74,999 | 10.0 | |

| $75,000 – $99,999 | 6.7 | |

| Missing data | 26.7 | |

| Age of the family member with DD | Less than 18 | 73.3 |

| 18 – 24 | 13.3 | |

| Missing data | 13.3 | |

| Disability type of the family member with DD | Autism | 70.0 |

| Speech/language impairments | 30.0 | |

| Intellectual disabilities | 26.7 | |

| Specific learning disabilities | 23.3 | |

| Developmental delay | 16.7 | |

| Multiple disabilities | 13.3 | |

| Emotional disturbance | 3.3 | |

| Visual impairments | 3.3 | |

| Sample size (N) | —– | 30 |

For interviews, there were a total of 14 parents who participated in the interviews. As shown in Table 2, of these participants, six primarily spoke English, five spoke Spanish, and three spoke Arabic; nine were Black, and five were White, of which six were Hispanic/Latino; 13 were female and one was male. The participants were predominantly middle-aged with seven individuals were ages 40-49 years, six ages 30-39 years, and only one aged 18-29 years. Most participants (n = 8) had a bachelor’s degree or associate degree; two completed high school or the equivalent; one did not complete high school; one earned some college credit but no degree; one completed some postgraduate work; and one had a postgraduate degree. Most of these families had a low household income. Four participants reported a household income at $0-$24,999; another four at $50,000-$74,999; one at $25,000 to $49,999; one at $75,000-$99,999, and one at $100,000 and above. Three participants did not report their household income.

| No. | Primary language | Gender | Age | Race/ ethnicity | Hispanic/ Latinx | Highest level of education | Household income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | English | Female | 40-49 | Black | No | Bachelor’s/associate degree | $50,000-$74,999 |

| P2 | Spanish | Female | 18-29 | White | Yes | Bachelor’s/associate degree | $0-$24,999 |

| P3 | English | Female | 30-39 | Black | No | Bachelor’s/associate degree | $50,000-$74,999 |

| P4 | Spanish | Female | 30-39 | White | Yes | High school/the equivalent | No answer |

| P5 | Arabic | Female | 40-49 | Black | No | Bachelor’s/associate degree | $50,000-$74,999 |

| P6 | English | Female | 40-49 | Black | No | Some postgraduate work | No answer |

| P7 | Spanish | Female | 30-39 | Black | Yes | Some college credit, no degree | $25,000-$49,999 |

| P8 | Arabic | Female | 40-49 | Black | No | Bachelor’s/associate degree | $100,000+ |

| P9 | Spanish | Female | 30-39 | White | Yes | Bachelor’s/associate degree | No answer |

| P10 | Arabic | Female | 40-49 | Black | No | High school/the equivalent | $0-$24,999 |

| P11 | English | Female | 30-39 | Black | No | Bachelor’s/associate degree | $75,000-$99,999 |

| P12 | Spanish | Female | 30-39 | White | Yes | Bachelor’s/associate degree | $0-$24,999 |

| P13 | Spanish | Male | 40-49 | White | Yes | Less than high school | $0-$24,999 |

| P14 | English | Female | 40-49 | Black | No | Postgraduate degree | $50,000-$74,999 |

Families’ Interactions with and Major Supports from Cultural Brokers

Based on the quantitative data of the survey, about 40% (n = 12) of parents reported that they met cultural brokers at a support group, conference, meeting, or other event; 33.3% (n = 10) reported that they were referred by parents, service agency, and other people; 6.7% (n = 2) found cultural brokers through a flyer or brochure; and 10% (n = 3) got to know cultural brokers in other ways. The time that parents worked with cultural brokers varied, ranging from 1 month to 3 years with anywhere between 2 to 30 interactions. Some participants in the interviews said they contacted cultural brokers very frequently. For example, one Latino/a/x parent (P4) said:

Every time when I feel I need her help, [I call her]. I can’t tell you exactly how many days or how many times or how many times a month, because it is like, it is mostly when I feel I need her help, because we catch up on the call every time except for the meeting. Now, we don’t meet [at other times] anymore because we have meetings like every week. We have a meeting with her every Tuesday. But after that, it was when I felt I needed her help.

Participants in the survey reported that the major support that cultural brokers provided was listening to their problems and issues (56.7%, n = 17), followed by helping to translate/ interpret information/materials they provided to the parent in their preferred language (53.3%, n = 16), educating them about the disability and education systems and other related services (50%, n = 15), connecting them or acting as a liaison with organizations that support people with DD (40%, n = 12), and attending a meeting with them to help support mediating misunderstandings between parents and schools/service providers (16.7%, n = 5).

Participants in the interviews also highlighted cultural brokers’ important roles as listeners, interpreters, educators, liaisons, and mediators. For example, a Latino/a/x parent (P2) said:

She [cultural broker] helped me, providing information and also explaining about the differences that I was confused about at first. And yes, she was able to help me, and she is still helping me clear up the confusions that I have, listening to me and still helping me when I have questions about schools, therapy and insurance. I still call her, and she is able to explain the differences to me.

A Black parent (P3) also commented:

She came with me to an IEP meeting, advocating to get more resources for my son. She kind of guided me through the process, and tried to help me be able to be more educated in the process and find the things I could act on as a parent, so that I could go into the meeting, like educated and be able to better advocate myself.

Families’ Overall Perceptions about Cultural Brokering Services

According to the quantitative data of the survey, participants provided a very positive rating of the cultural brokering Parent to Parent support. Almost all participants (96.7%, n = 29) were satisfied with the services provided by cultural brokers, with 66.7% (n = 20) participants very satisfied with the support and 30.0% (n = 9) satisfied with the support. Specifically, as show in Table 3, a total of 83.4% (n = 25) participants reported that it was “always” or “most of the time” easy to reach cultural brokers; about 86.7% (n = 26) reported that they “always” or “most of the time” received timely response from cultural brokers; and 90.0% (n = 27) reported that cultural brokers “always” or “most of the time” did the things that they said they would do.

| Statements | Always (%) | Most of the time (%) | Some of the time (%) | Rarely/ Never | Missing data (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It is easy to reach cultural brokers. | 56.7 | 26.7 | 10.0 | 0 | 6.7 |

| Cultural brokers respond to emails/calls timely. | 50.0 | 36.7 | 6.7 | 0 | 6.7 |

| Cultural brokers do the things they say they will do. | 63.3 | 26.7 | 3.3 | 0 | 6.7 |

| Strongly agree (%) | Agree (%) | Disagree (%) | Strongly disagree (%) | Missing data (%) | |

| Cultural broker worked with me to figure out the needs of my family. | 56.7 | 36.7 | 0 | 0 | 6.7 |

| Cultural broker knew my culture well. | 63.3 | 30.0 | 0 | 0 | 6.7 |

| Cultural broker respected my choices and preferences. | 63.3 | 30.0 | 0 | 0 | 6.7 |

| Cultural broker communicated effectively with me. | 66.7 | 23.3 | 0 | 0 | 10.0 |

| Cultural broker stayed in touch with me until my issue was resolved. | 50.0 | 30.0 | 6.7 | 0 | 13.3 |

Additionally, most of the participants (93.3%, n = 28) agreed that cultural brokers worked with them to figure out the needs of their families; 93.3% (n = 28) agreed that cultural brokers knew their culture well; 93.3% (n = 28) agreed that cultural brokers respected their choices and preferences; 90% (n = 27) agreed that cultural brokers communicated effectively with them; and 80% agreed that the cultural brokers stayed in touch with them until their issues were resolved.

The findings from the quantitative data of the survey were consistent with the qualitative data of the survey and interviews where a majority of participants commented that cultural brokers were very knowledgeable and helpful, understood their situations, knew their languages, listened to and supported their families with an open heart and mind, related to and empathized with families, walked them through the service process, and helped them plan and prepare for the future, etc. For example, one Black parent (P1) shared the following in the interview:

She [cultural broker] was able to let me know about some of the rules…. They [school] would tell him that I had to come and pick him up but wouldn’t give me the paperwork. So, she [cultural broker] told me that, by law, they would have to give me paperwork saying that they’re suspending him…. She [cultural broker] also told me about the behavior plan because I didn’t know anything about that. I was able to talk to the school about getting that going….

Another Black parent (P14) appreciated the support that cultural brokers provided in guiding them through the service process:

Having that one person [cultural broker] that you can consistently look to for answers is an awesome tool to have. You know, because a lot of times we attend information sections and get a packet of information…. And then you get back home, and you are like, “so, how do I work on this?” And there is not really anybody to reach back out to. But with the [cultural broker program], it is kind of like here is your packet, start with step one and two, and then come back and touch base with step three if you have questions. I think that will help families better reach goals because they are not alone in that [process].

Effectiveness of Cultural Brokering in Meeting Families’ Needs

Most participants reported that cultural brokers did a great job in meeting the needs of their families and solving problems they experienced with having a child with DD by providing information; connecting parents with individuals, agencies, and other resources; educating them about disability related systems; and sharing personal stories. For example, one Black parent (P6) had difficulties with getting an IEP and Medicaid for her son with DD and shared how a cultural broker helped her to successfully obtain these services:

She [cultural broker] called my number and asked me what the problem was. I told her everything. She sent somebody to talk to me. The person came to school with me…. We had a meeting [with the school]. They [school] said they’ve agreed to meet with me to discuss my son’s education issue…. So, through them, my son was able to go up to school. And we [started doing] the IEP plan for him.

Another thing that I asked her is if there is any way we can get some benefits if we are qualified to… what we had was not enough to even feed us.… She [cultural broker] told us to go to social security and see if we were entitled to get Medicaid. So, we went with the instructions she [cultural broker] gave us and everything….They told us we were entitled, you know, for Medicaid. Now, we have insurance.

One Latino/a/x parent (P12) had a son who was newly diagnosed with Autism, and she was lost about what to do with a child with Autism. She reached out to the cultural broker who connected her with all the services that she needed. She commented:

He [cultural broker] referred me to people [service providers] with whom I am now working. They provide me with a better idea about how to do things. Now, I have a team, speech therapies, behavior therapies, occupational therapies, you know, neologies. All these people are helping me with my son, and [I] also [have] the support that I have in every meeting with him [cultural broker] and others. At the personal level, me as a mom at first and dealing with all these…I am able to understand what is going on and how to help my son and give myself rest, and at the same time, learn more. I feel more in control with everything that happens in his [the son with Autism] life.

In particular, participants frequently mentioned the value and importance of the support groups organized by cultural brokers in helping them to get information, learn new things, share experiences, and get advice and support from other parents. For example, one Black parent (P5) mentioned the continuous support she received from the support group for Sudanese parents organized by the cultural broker:

We have a group. It is a personal group in which we talk about all these [disability related issues and services] as moms. And you know, as moms, as families, we talked about issues that our kids have, how to help each other and how to support each other. And she [cultural broker] has been a great help, giving us information, especially if someone in the group asks about specific things. She [cultural broker] was very good and provided information or a link that can help about that…And she [cultural broker] has been open in mind and open ears for us. We usually support each other and everyone else as much as possible.

A Latino/a/x interview participant (P9) also shared the value of the support group for Spanish speaking families in helping her child with disabilities:

The meetings [of the support group] is directed to the Spanish speaking families…. The topics are all autism related…. There are different topics that are being shared in the talks in the meetings. They [meetings] give us a lot of good information about what is going on and what resources are available to us. We also get to share experiences. Our kids are [in] different ages. I feel that is good, because it gives me a glimpse of what could expect for my son growing up and things that I have to watch out for. [For example], when he grows up, I need to look for, like, paying for him to be taken care of. I need to, maybe, get counseling for him, like ABA [Applied Behavior Analysis] in the region, things like that.

Areas for Improving Cultural Brokering and the Parent to Parent Support Program

While participants highlighted a lot of positive experiences and desirable outcomes through working with the cultural brokering Parent to Parent support program, a few participants mentioned challenges they had with the cultural brokering support and provided suggestions to help improve the program overall. Major challenges mentioned by study participants were: (1) the time schedule of support group meetings, (2) the online only option for support group meetings during the pandemic, and (3) the insufficient advertisement about the program. They suggested solutions such as the following.

- Finding multiple ways to advertise the cultural brokering Parent to Parent support program to increase families’ awareness of the services.

- Offering more time options as well as in-person meetings for the support groups.

- Having both group discussions and one-on-one discussions with parents, including in-person assistance (not just telephone).

- Having cultural brokers that represent male and LGBTQ communities, for example.

- Providing brochures and other materials in different languages such as Spanish and Arabic.

- Offering more training to parents to help them understand issues related to raising a child with DD.

For example, one Black parent (P14) suggested the need of advertising the cultural brokering service:

I wish more people knew about it [cultural brokering service] because I think a lot of people could benefit from it…when I talk with families and try to send them to the program. They never heard of it…. I mean, I work with doctor’s offices and schools. When I mention the program, I would say 95 % of the time they never heard of it. They don’t know…. So, finding ways to let families know that you are here, specially, the cultural broker part. That is so awesome, because usually the resources are for the typical American English-speaking families. And when you have these different cultural brokers, that can help bridge those gaps. You really want to get that word out.

Another Black parent (P11) recommended the importance of having men and members from LGBTQ communities as cultural brokers to better support different people:

Some of the people that need help, I assume, are men. Having a cultural broker that is specifically male or transgender [would be helpful], because a man’s experience, like my husband, his experience as a man helping with the children is completely different than mine as a woman. So, having a man as a cultural broker, that would be pretty cool. And also having someone that identifies as LGBTQ, that is a whole different thing. Having those two things would be great.

An Arabic-speaking parent (P5) who had difficulties in applying for Medicaid highlighted the importance of in-person assistance especially for parents with language barriers:

I don’t know if you [cultural brokers and the Parent to Parent support program] have someone who can support the family physically. But now I know [things] cannot be done but maybe even by phone. Help them [families] apply for the right [Medicaid] waivers and the right resources because I have… This is what I have been facing in the last couple of months. [I] tried to apply for waivers and resources and got denied just because there was something in that application that I did not fill in in the right way or did not say the right words. I have been facing all those struggles.

Discussion and Implications

The initiative in this study is a statewide program using the intersection of cultural brokering theory and the Parent to Parent support model. The findings of this study provided evidence to support the promising outcomes of this initiative in supporting culturally diverse families of children with DD, which is consistent with the findings of prior studies (Pang et al., 2019, 2020). This study adds to the literature by providing evidence from the perspective of families who receive cultural brokering service and further identifies the value and effectiveness of service models or interventions that recognize the diversity and differences in the culture, belief, experiences, and needs of families who have a child with DD and who also come from a minority cultural background (Bray et al, 2017; Dodd et al, 2009; Holloway et al., 2018). As discussed earlier, culturally diverse families of children with DD share multiple and intersecting identities, such as race, ethnicity, gender, country origins, religion, language, disability, and socioeconomic status, and they often have different understanding of disability, unique perspectives about the life and goals of a family member with DD, and divergent experiences with the disability system (Banks, 2018; Brandon & Brown, 2009; Ishimaru et al., 2016). Meeting the needs of culturally diverse families of children with DD requires service program professionals recognizing not only the problems and barriers related to disabilities that culturally diverse families are experiencing, but also the cultural context and other identities of these families that may impact their understanding of the service systems as well as their approach to obtain services (Dodd et al., 2009).

The cultural brokering initiative in this study is a culturally responsive family support model that recognizes and values the different experiences of culturally diverse families of children with DD (Achola & Greene, 2016; Holloway et al., 2018). It also acknowledges the positive benefits of a peer partnership in which parents are interacted with and supported in ways that are meaningful and effective to them (Henderson et al., 2016). In this study, parents noted that from the cultural brokering support, they accrued knowledge and skills, built confidence, learned new ideas and experiences, and successfully secured services and resources. They particularly valued the support groups that shared cultural/linguistic backgrounds and similar experiences. In addition, they noted that all of this culturally responsive support helped them better manage life with a child with DD and achieve the goals of their family. This study constitutes a framework, the intersection of the cultural brokering model and the Parent to Parent support model, that more effectively supports culturally diverse families of children with DD and oftentimes improves the service outcomes of these families.

The roles of cultural brokers identified in this study are consistent with our prior study (Pang et al., 2020). One difference in the prior study was key informants noting “advocacy” as a major role of cultural brokers, which is also a role supported by the cultural brokering model of Jezewski and Sotnik (2005). The cultural brokers in our study did not consider “advocacy” as one of their primary roles (Pang et al., 2020). Instead, cultural brokers said they educated and empowered parents to become a strong advocate for themselves and their children with DD, which is the mission of the Parent to Parent support program. Consistently, parents in this study did not identify “advocacy” as a major role of cultural brokers, even though they mentioned that in some meetings, cultural brokers did speak on their behalf in attempts to assist with communication and negotiation in order to get the greatest benefits for the child with DD. However, they noted that was not the cultural broker’s’ major role. Most parents pointed out the cultural brokers’ major roles as listeners, interpreters, educators, liaisons, and mediators, which is consistent with the perspectives of cultural brokers in the prior study (Pang et al., 2020).

To better guide the implementation of cultural brokering with families of children with DD, researchers should provide clearer context for the roles of cultural brokers at different levels (i.e., individual support level as is described in this study, the organizational support level, and the policymaking level), and service providers should be clear about the level of their cultural brokering service and clarify the major roles and responsibilities for cultural brokers when designing and implementing their own cultural brokering initiative.

While this study identifies the value and positive outcomes of the cultural brokering initiative embedded in a UCEDD’s Parent to Parent support program, it raises questions about the effective ways for cultural brokers to support the diverse needs of all culturally diverse families of children with DD, for example, whether the program should offer one-to-one support versus group support. Some parents in this study reported that they favored one-on-one discussions because they could better express themselves. Other parents emphasized the benefits of group discussions and group information sessions where they enjoyed being connected with other peer parents and learning from one another. Some parents in this study also shared that they needed in-person assistance, such as help filling out an application, because it was difficult and time-consuming to address some of their problems on the phone. Some parents stated they preferred attending the support group meetings through video because it was more flexible in time and location, while other parents wanted to join the meetings in person where they could meet and build relationships with cultural brokers and other parents. Parents’ divergent preferences for how they want to be supported reflects only one facet of the complexity, diversity, and variability in meeting the needs of culturally diverse families of children with DD. It is hard to reach consensus on the most effective ways because parents from different cultural communities may have different preferences. Parents within the same cultural community may not even agree with each other on how they want to receive the support (Dodd et al., 2009; Hanson & Lynch, 1992; Parette et al., 2004). It takes time for cultural brokers to learn from the communities they support and determine the effective ways to reach out to parents and to deliver support. It requires cultural brokers being flexible and offering different options to parents, when possible.

Another question is whether the program should have more cultural brokers who represent different racial/ethnic communities and where is the line of tokenizing a group of people by having one cultural broker for that community. The cultural brokering initiative in this study recruited and trained cultural brokers who represented African American/Black, Latino/a/x, Asian, Arabic and refugee communities. The UCEDD’s Parent to Parent support program typically has four to five cultural brokers employed in a given year and is conscious of the fact that one person cannot fully represent all perspectives of their racial/ethnic community. The program recruits parents, siblings, and grandparents to serve as volunteer family navigators; many of whom identify as culturally diverse and who are available to support the cultural brokers. While the UCEDD’s state demographics support cultural brokers working with Black/African American, Arabic, Korean and Latino/a/x communities, there are gaps in effectively serving other minority communities, such as Vietnamese and Chinese communities, that are prevalent in other regions of the state. In addition, current cultural brokers focus on identities such as race, ethnicity, and country origins. Some of the parents in the study also identify the necessity of having cultural brokers represent fathers of children with disabilities and LGBTQ communities, which extends the focus to other identities such as gender and sexual orientation. As culturally diverse families of children with DD often share multiple intervening identities such as disability, gender, country origin, language, race, ethnicity, and/or socioeconomic status, it is challenging and even impossible to have cultural brokers to represent all these different identities shared by families (Banks, 2018; Brandon & Brown, 2009; Ishimaru et al., 2016). It is important for the program to work closely with families to identify the important identities that a cultural broker should share with them and to make sure the cultural brokers are culturally agile to better understand the situations and barriers of families and provide support in appropriate ways that meet each family’s unique needs.

There are a few limitations in this study. Our study focused on one statewide Parent to Parent support program and had a small survey sample, which makes it hard to generalize the research findings to another program. In both the survey and the interview, there was only one participant who was between 18 and 29 years old, which makes it hard to apply the findings of this study to a younger generation of parents of children with DD. In addition, the participants in the program were from African-American, Arabic speaking and Latino/a/x communities that are most frequently referred to or reaching out to this UCEDD’s Parent to Parent support program. There were no participants from other racial/ethnic backgrounds such as Asian, Tribal, and biracial families in this study, who might have received support from a cultural broker in the program. Most of the study participants were mothers (two fathers answered the survey and one father participated in an interview). Thus, the findings of this study were not reflective of broader cultural perspectives (i.e., racial, ethnic, gender) about cultural brokering. Future research should consider gathering the perspectives of other racial or ethnic groups, male parents, and parents of younger ages to get a more comprehensive understanding of the experiences with, and effectiveness of, cultural brokering support.

Conclusion

The intervening identities, different experiences, and divergent needs of culturally diverse families of children with DD create great challenges for service providers to understand their situations and meet their needs. This study presented a cultural brokering initiative, based on the intersection of the cultural brokering model and the Parent to Parent support model, to better support culturally diverse families of children with DD. The findings of this study provide evidence support for the positive outcomes of the cultural brokering initiative and offer important insights for the future development of a cultural brokering theoretical framework for families of children with DD as well as for the implementation of cultural brokering in Parent to Parent support programs.

References

Achola, E. O., & Greene, G. (2016). Person-family centered transition planning: Improving post-school outcomes to culturally diverse youth and families. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 45(2), 173-183. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-160821

Anderson, L. S. (2009). Mothers of children with special health care needs: Documenting the experience of their children’s care in the school setting. The Journal of School Nursing, 25(5), 342-351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840509334146

Banks, J. (2018). Invisible man: Examining the intersectionality of disability, race, and gender in an urban community. Disability & Society, 33(6), 894-908. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018. 1456912

Brandon, R. R., & Brown, M. R. (2009). African American families in the special education process: Increasing their level of involvement. Intervention in School and Clinic, 45(2), 85-90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451209340218

Bray, L., Carter, B., Sanders, C., Blake, L., & Keegan, K. (2017). Parent-to-parent peer support for parents of children with a disability: A mixed method study. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(8), 1537-1543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.03.004

Brookman, B. A. (1988). Parent to Parent: A model for parent support and information. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 8(2), 88-93. https://doi.org/10.1177/027112148800800210

Burch, P., & Heinrich, C. J. (2015). Mixed methods for policy research and program evaluation. Sage Publications.

Cooper, C. R., Denner, J., & Lopez, E. M. (1999). Cultural brokers: Helping Latino children on pathways toward success. The Future of Children 9(2), 51-57. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602705

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Dodd, J., Saggers, S., & Wildy, H. (2009). Constructing the ‘ideal’ family for family‐centered practice: Challenges for delivery. Disability & Society, 24(2), 173-186. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 09687590802652447

Dodds, R. L., & Walch, T. J. (2022). The glue that keeps everybody together: Peer support in mothers of young children with special health care needs. Child: Care, Health and Development, 48, 772-780. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12986

Dodds, R. L., Yarbrough, D. V., & Quick, N. (2018). Lessons learned: Providing peer support to culturally diverse families of children with disabilities or special health care needs. Social Work, 63(3), 261-264. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swy019

Dyrness, A. (2011). Mothers united: An immigrant struggle for socially just education. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Freedman, R. I., & Boyer, N. C. (2000). The power to choose: Supports for families caring for individuals with developmental disabilities. Health & Social Work, 25(1), 59-68. https://doi.org/10.1093/ hsw/25.1.59

Garwick, A. W., Patterson, J. M., Bennett, F. C., & Blum, R. W. (1998). Parents’ perceptions of helpful vs unhelpful types of support in managing the care of preadolescents with chronic conditions. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 152(7), 665-671. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/archpedi.152.7.665

Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 629-642. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y

Hanson, M. J., & Lynch, E. W. (1992). Family diversity: Implications for policy and practice. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 12(3), 283-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/027112149201200304

Henderson, R. J., Johnson, A. M., & Moodie, S. T. (2016). Revised conceptual framework of parent-to-parent support for parents of children who are deaf or hard of hearing: A modified Delphi study. American Journal of Audiology, 25(2), 110-126. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_AJA-15-0059

Holloway, S. D., Cohen, S. R., & Domínguez-Pareto, I. (2018). Culture, stigma, and intersectionality: Toward equitable parent-practitioner relationships in early childhood special education. In M. Siller & L. Morgan (Eds.), Handbook of parent-implemented interventions for very young children with autism (pp. 93-106). Springer.

Ishimaru, A. M., Torres, K. E., Salvador, J. E., Lott, J., Williams, D. M. C., & Tran, C. (2016). Reinforcing deficit, journeying toward equity: Cultural brokering in family engagement initiatives. American Educational Research Journal, 53(4), 850-882. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216657178

Jezewski, M. A. (1995). Evolution of a grounded theory: Conflict resolution through culture brokering. Advances in Nursing Science. 17(3), 14-30.

Jezewski, M. A., & Sotnik, P. (2005). Disability service providers as cultural brokers. In J. H. Stone (Ed.), Culture and disability: Providing culturally competent services (pp. 37-64). SAGE Publications.

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112-133. https://doi.org/10.1177/155868 9806298224

Lewis, A., & Diamond, J. B. (2015). Despite the best intentions: How racial inequality thrives in good schools. Oxford University Press.

Lindsay, S., King, G., Klassen, A. F., Esses, V., & Stachel, M. (2012). Working with immigrant families raising a child with a disability: challenges and recommendations for healthcare and community service providers. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(23), 2007-2017. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288. 2012.667192

McCabe, H. (2008). The importance of parent‐to‐parent support among families of children with autism in the People’s Republic of China. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 55(4), 303-314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120802489471

Mirza, M., & Heinemann, A. W. (2012). Service needs and service gaps among refugees with disabilities resettled in the United States. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(7), 542-552. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.611211

Mueller, T. G., Milian, M., & Lopez, M. I. (2009). Latina mothers’ views of a parent-to-parent support group in the special education system. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 34(3-4), 113-122. https://doi.org/10.2511/rpsd.34.3-4.113

Pang, Y., Dinora, P., & Yarbrough, D. (2020). The gap between theory and practice: using cultural brokering to serve culturally diverse families of children with disabilities. Disability & Society, 35(3), 366-388. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1647147

Pang, Y., Yarbrough, D., & Dinora, P. (2019). Cultural brokering intervention for families of children receiving special education supports. In L. Lo & Y. Xu (Eds.), Family, school, and community partnerships for students with disabilities (pp. 127-138). Springer.

Parette, P., Chuang, S. J. L., & Blake Huer, M. (2004). First-generation Chinese American families’ attitudes regarding disabilities and educational interventions. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19(2), 114-123. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576040190020701

Rotich, J. P., & Kaya, A. (2014). Critical role of lay health cultural brokers in promoting the health of immigrants and refugees: A case study in the United States of America. Journal of Human Sciences, 11(1), 291-302. https://doi.org/10.14687/ijhs.v11i1.2723

Santelli, B., Turnbull, A., & Higgins, C. (1997). Parent to parent support and health care. Pediatric Nursing, 23(3), 303-307.

Solomon, M., Pistrang, N., & Barker, C. (2001). The benefits of mutual support groups for parents of children with disabilities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(1), 113-132. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005253514140

Szente, J., Hoot, J., & Taylor, D. (2006). Responding to the special needs of refugee children: Practical ideas for teachers. Early Childhood Education Journal, 34(1), 15-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-006-0082-2

Winch, A. E., & Christoph, J. M. (1988). Parent to Parent links: Building networks for parents of hospitalized children. Children’s Health Care, 17(2), 93-97. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326888chc1702_6

Woodgate, R. L., Ateah, C., & Secco, L. (2008). Living in a world of our own: The experience of parents who have a child with autism. Qualitative Health Research, 18(8), 1075-1083. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1049732308320112

Woodman, A. C., Mawdsley, H. P., & Hauser-Cram, P. (2015). Parenting stress and child behavior problems within families of children with developmental disabilities: Transactional relations across 15 years. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36, 264-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014. 10.011

Yohani, S. (2013). Educational cultural brokers and the school adaptation of refugee children and families: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 14(1), 61-79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-011-0229-x