4 Paths to Equity: Parents in Partnership with UCEDDs Fostering Black Family Advocacy for Children on the Autism Spectrum

Elizabeth H. Morgan; Benita D. Shaw; Ida Winters; Chiffon King; Jazmin Burns; Aubyn Stahmer; and Gail Chodron

Morgan, Elizabeth H.; Shaw, Benita D.; Winters, Ida; King, Chiffon; Burns, Jazmin; Stahmer, Aubyn; and Chodron, Gail (2023) “Paths to Equity: Parents in partnership with UCEDDs fostering Black family advocacy for children on the autism spectrum,” Developmental Disabilities Network Journal: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 5.

Plain Language Summary

Racism and ableism cause many negative outcomes for Black children and their families in health care and education. Many Black families wait a long time to get a diagnosis for their child with a developmental disability. Black families also get low-quality care. In this paper, we describe how two UCEDDs partnered with Black parents to support advocacy and peer networking for Black families. Three co-authors who are Black parents describe our negative experiences with schools and health care. We also talk about our lived experience partnering with UCEDDs. There are several steps we need to take to make sure Black families get quality care. One thing we need to do is listen to Black families describe their lived experience. We should support Black families to raise their voices, and we should do more qualitative research about family experiences. It is also important for providers to change how they think and act. Providers need to understand how their biases impact Black families. UCEDDs and Black families can partner to help make these changes happen.

Abstract

Racism and ableism have doubly affected Black families of children with developmental disabilities in their interactions with disability systems of supports and services (e.g., early intervention, mental health, education, medical systems). On average, Black autistic children are diagnosed three years later and are up to three times more likely to be misdiagnosed than their non-Hispanic White peers. Qualitative research provides evidence that systemic oppression, often attributed to intersectionality, can cause circumstances where Black disabled youth are doubly marginalized by policy and practice that perpetuates inequality. School discipline policies that criminalize Black students and inadequate medical assessments that improperly support Black children with developmental and mental health disabilities are examples of systemic oppressions. However, there is evidence to support that attitudes and biases that providers hold about Black children, and their families hold a part in the blame as well. This paper will explore the efforts of two University Centers for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCEDDs) to address disparities in access to diagnostic and higher quality services for Black neurodiverse children in Northern California and Wisconsin. This paper will: (1) Describe programs and projects within each center that support advocacy and peer networking for Black families; (2) Provide first-person accounts from family members that document the UCEDDs’ impact on their respective advocacy journeys; (3) Delineate how each UCEDD partnered with Black families and community stakeholders to develop and plan programs that meet the unique interests and needs of the groups of Black families of autistic children within the cultural contexts of the communities in which they live; (4) Discuss the processes that each UCEDD underwent to evaluate the efficacy of their programs to ensure that they were uplifting principles of cultural and linguistic competence such as community and family engagement; and (5) Offer recommendations to improve current practice and create culturally competent and family-centered supports and services for disability systems and providers across the DD Network and beyond.

Introduction

“I believe that my experience as an autistic person has definitely been affected by my gender and race. Many characteristics that I possess that are clearly autistic were instead attributed to my race or gender. As a result, not only was I deprived of supports that would have been helpful, I was misunderstood and also, at times, mistreated.” –Morénike Giwa Onaiwu (Rozsa, 2016)

Author, advocate, educator, Morénike Giwa Onaiwu’s quote illustrates the intersectional barriers that Black autistic children face when interacting with people within service delivery systems (e.g., schools, medical, early intervention) who are not properly trained to support children from BIPOC communities. In this commentary we used duoethnographic methodological techniques to allow all authors to be participants in communicating the experience of creating programming in UCEDDs for the purpose of supporting Black autistic children and their families. This paper is written by and with researchers and Black mothers of children with developmental disabilities to illustrate the types of collaboration that is necessary to provide culturally inclusive practice in service delivery institutions. We will address the obstacles that Black autistic people and their families face when navigating service delivery systems and give suggestions for how to ameliorate these systems to serve all families.

First, we will discuss the importance of parent advocacy for children on the autism spectrum and discuss the barriers that families of Black children with developmental disabilities such as autism spectrum disorder face when interacting with service delivery systems. Next, we will give background to why culturally competent programing for Black families is a key element to dismantling the historical trauma and harm the educational and medical institutions have inflicted on the Black American community and to increasing equity in services. We will then introduce two University Centers for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCEDDs) and share their commitment to working to create culturally competent programming that supports the needs of Black families in Northern California and Wisconsin. Next, mother advocates share their perspectives on the work being done through these community-partnered projects. Last, we will give suggestions and recommendations of promising practices other UCEDDs and service delivery agencies can use to effectively engage and support Black families of children with disabilities.

Methods

Methodology

Duoethnography is a dialogic qualitative research methodology that allows researchers to be participants and participants to be researchers to better understand the answers to elusive questions (Bhattacharya, 2020; Brown, 2015; Sawyer & Norris, 2012). This methodology was chosen because it allows for a reframing of the humanity, interrelationships, and social justice nuances needed to discuss mindset changes and actions for creating change in current systems of care to better support the needs, desires, and wants of Black autistic children and their families.

Positionality of Researchers/Participants

The confluence of positionalities of the authors is multifarious in diversity of experience and background but unified in their goals of desiring to elucidate and reimagine the current service delivery models used to better support all neurodivergent children and their families. In this paper, the lead author is both a trained research scientist with a doctorate in human development and a Black mother of an autistic son in California. The second author is a community advocate, UCEDD program specialist, and Black mother of an autistic child in Northern California. The third and fourth authors are both Black mother advocates who do work with the Wisconsin UCEDD. The fifth author is a Black psychologist whose work focuses on supporting the mental health needs of Black autistic youth in California and Texas. The sixth and seventh authors identify as White female trained research scientists who are directors of UCEDDs/LENDS in Northern California and Wisconsin. The combined perspectives of all authors created an article that centers the experiences of the Black mother advocates to demonstrate the pernicious obstacles that Black parents face when interacting with service delivery systems while giving evidence on what can be done to ameliorate these systems. In the next section of this paper, an account of the historical marginalization of Black families from enacting their advocacy is given to ground the reader and gives context to the need for intervention programming.

Importance of Parent Advocacy in Autism Diagnosis and Treatment

Parents of children on the autism spectrum have historically been responsible for advocating for their child’s rights to inclusion and access in schools, communities, and public spaces (Ryan & Runswick-Cole , 2009). Dr. Leo Kanner diagnosed the first children in the U.S. with the disability we know as autism in 1943 (Angell & Solomon, 2014; De Wolfe, 2016; Silverman, 2011; Zarembo, 2011). Dr. Kanner’s paper, “Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact,” described his observation of 11 children who had limited abilities to engage in spontaneous social activities, difficulty generalizing, and engaged in stereotypic and repetitive behaviors. Dr. Kanner was approached by parents of children because they believed that their child’s diagnosis of cognitive impairments (then called mental retardation) was not appropriate, and they sought additional consultation to support their “cognitive potentialities” and hoped for restorative treatment (Grinker, 2008; Kanner, 1943). As we approach the 80th year since the first autism diagnosis in the U.S., the role of parental advocacy in obtaining a diagnosis and treatment for autistic children remains consequential (Angell & Solomon, 2014; Silverman, 2011; Zarembo, 2011).

There are several factors that contribute to early diagnosis and treatment, but the most critical factor is a powerful parent advocate (Angell & Solomon, 2014; Behrens et al., 2022, Gourdine et al., 2011; Harstad et al., 2013; Hassrick, 2019; Wilson, 2015). The literature depicts the vital role parents have played in the identification and treatment of autistic children. Parents handle the care of a child, but parents of children on the autism spectrum are also responsible for advocating for that child’s rights to equal inclusion and access in schools, communities, and public spaces (Ryan & Runswick-Cole, 2009). Black parents of children on the autism spectrum also share the identity of advocate, but because of the social construct of race and other intersectional variables, the pathway to becoming an advocate includes different experiences and support needs (Burkett et al., 2015; Kaiser et al., 2022; Lovelace et al., 2018; Morgan et al., 2022; Pearson & Meadan, 2021; Stahmer et al. 2019; Wilson; 2015). To better understand the pathway Black families take to become parent advocates, we must first understand the additional challenges these families face before and after their children are diagnosed.

Disparities in Autism Diagnosis for Black Children

Delays in the age of identification of autism for Black children were first identified over two decades ago when researchers reviewing Medicaid mental health claims determined Black children were identified, on average, over a year later than White children and required more time in treatment before receiving a diagnosis (Mandell et al., 2002). When looking at early childhood records more recently, most research continues to report that, on average, Black autistic children are diagnosed 3 years later and are up to three times more likely to be misdiagnosed than their non-Hispanic White peers (Constantino et al., 2020; Daniels & Mandell 2013; Mandell et al., 2007, 2009; Wiggins et al., 2019; Yeargin-Allsopp et al., 2003).

Disparities in timeliness of autism identification for Black children is not evident in the most recent surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) network, which examined autism prevalence among children aged 4 years and 8 years old in 2018 (born in 2014 and 2010, respectively; Maenner et al., 2021; Shaw et al., 2021), although a gap of over 1 year in time to diagnosis was still evident in ADDM network surveillance data for children who were 8 years old in 2014 (born in 2008; Baio et al., 2018). Moreover, a more nuanced analysis of ADDM network surveillance data collected between 2008 and 2016 suggests the gap for Black children is closing primarily for those who have co-occurring intellectual disability (Shaw et al, 2021). Additionally, a recent study by Constantino et al. (2020) examining the diagnostic odyssey of 584 Black children with autism enrolled in a large representative research study found Black children were not given an autism diagnosis, on average, for 3.5 years after their parents first reported being worried about their child’s development even though over 90% had insurance coverage at the time of first concern. Many families reported waiting a long time before seeing a professional, and many visited multiple professionals before getting an autism diagnosis. Of note, over 40% of Black children included in the study received a different diagnosis before being identified with autism through the diagnostic assessment administered as part of the study.

Disparities in autism screening present the first challenge to timely diagnosis for black children. Arunyanart (2012) found that autism-specific screening in primary care was significantly mediated by the racial and socioeconomic composition of the patient population. Namely, autism screening was significantly less likely to be conducted for patients in practices where over 30% of patients were covered by Medicaid compared to practices with 10-30% of patients covered by Medicaid. This means that many Black children will not be identified as having autism or other developmental disabilities until they reach school age. However, schools also show disparities in identification practices, with autism identification in schools being significantly higher for White students than Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaskan Native students, who are more likely to be placed incorrectly into other special education categories (Sullivan, 2013). Examining Wisconsin Department of Instruction data representing 895,791 students in the 2010-11 school year, Fish (2019) found that the racial composition of public schools had a significant effect on how special education categorizations were allocated by race. Black children attending schools with White students in the majority were significantly more likely to access special education through more stigmatized disability categories (i.e., emotional disturbance or intellectual disability) compared to White children in the same school and compared to Black children attending schools with a far lower proportion of White students.

Delays in diagnosis are important because a diagnosis leads to access to autism-specific services. Even though autism can be reliably identified by age 2, most Black children do not receive a diagnosis until after age 4. This means they start treatment later than White children and do not have a chance to benefit from early intervention (Yingling & Bell, 2018). Once diagnosed, children from underrepresented groups, such as Black children, are less likely to access autism-related services (Thomas et al., 2007) including subspecialty care (e.g., gastroenterology, neurological testing [Broder-Fingert et al., 2013]) and school-based interventions (Locke et al., 2017). Thus, for Black children to obtain an early and accurate autism diagnosis, Black parents must develop a perspicacity of skills to successfully navigate service delivery systems.

Racial formation theory posits that race is both a social and political construct developing from social and economic history, which creates hierarchy and separation between groups of people because of unequal treatment and unbalanced distribution of rewards and resources based on pigmentation (Omi & Winant, 2015). According to Racial formation theory, race is a political construct with multiple influencing factors, such as personal self-identification and social interactions. Societal ideologies, misconceptions, and stereotypes about racial groups also influence the racialized experience of the individual within the groups. In postcolonial cultures, such as in the Americas, class and race are highly correlated because of the historic foundation of enslavement of Black people created during colonization. This led to the development of social practices that created and maintained a social hierarchy, economy, and mobility based on skin pigmentation (Hernández, 2015). The race-based politics and institutional racist systems developed to maintain and perpetuate inequality and unequal access to resources via the racial caste system remain the foundation of current U.S. ideology and ethos around race and race relations (Borunda et al., 2020; Dumas & ross, 2016; West, 2018). The social construct of race holds a gravitas in the U.S., thus affecting the effort and challenges associated with advocating within social and service institutions such as schools and medical systems that serve autistic children.

Therefore, Black families in the U.S. navigating service systems for their children on the autism spectrum not only deal with the excessively complicated administrative procedures associated with school and medical intervention systems, but they also must navigate and learn to advocate within the “imperialist, white-supremacist, capitalist, patriarchy” ideology that is at the foundation of these systems (hooks, 1996, 2014). This racism has led to systematic delays in autism identification and reduced access to high-quality services. Hence, understanding the role of intersectional identities of Black families is imperative to understanding the formation of advocate identity for Black parents of children on the autism spectrum.

Intersectionality in Black Parent Advocacy Pathways

Intersectional identities deepen the challenge for Black mothers of autistic children. The term “intersectionality” was first coined by civil rights lawyer Kimberlé Crenshaw to frame the magnification of social problems that occur when people experience multiple identities associated with social discrimination (Crenshaw, 1989). Dr. Crenshaw coined this term after researching legal case law that insufficiently protected the needs of Black women in the workforce. According to her research, Black women received no justice in the legal system because the courts had no precedent to understand the interaction of racism and sexism in discrimination cases. The courts repeatedly denied Black women justice when they experienced racist and sexist discriminatory treatment because of their intersectional doubly discriminated identities.

Intersectionality is now a term for socially marginalized people who embody multiple identities, including those affected by racism, sexism, classism, xenophobia, transphobia, heterosexism, and ableism (Gopaldas, 2013; Harris & Patton, 2018). We must also consider the impact of intersectionality for Black families of autistic children, as there is a myriad of overlapping intersections such as race, gender, class, plus disability that commonly occur and affect their experiences. Black autism families follow a complex intersectional pathway to discover their voices and learn how to advocate for their children, requiring them to draw from previous experiences of navigating challenges of social stratification (e.g., racism, sexism, classism) to address a new intersectional aspect of their identity—becoming a parent advocate (Ocasio-Stoutenburg, 2021).

Research in schools clearly identifies challenges specific to Black families. Black families report distinct stereotypes and prejudices associated with a racist ideology that serve as barriers for Black mothers during the IEP process. Black mothers speak of negative reputations being spread by special education staff describing them being “adversarial, dysfunctional, uncaring” and that their input during meetings is an “untrustworthy source of information” (Stanley, 2015). Wilson (2015) conducted a qualitative study involving interviews with eight working-class Black parents to understand more about the role their socioeconomic class and educational attainment had in their ability to actively participate and personally advocate for their child during school intervention team meetings. Wilson found that during mandated annual meetings for special education services, also known as Individualized Education Plans (IEP) meetings, these Black families did not have the critical communicative skills—such as question asking—to navigate the meetings and secure appropriate services for their children (Wilson, 2015). To support these difficulties, when asked, providers acknowledge the challenges they have partnering the families of color and report mistrust and presence of cultural mismatching as a potential cause of said challenges (Harry, 2002; Kaiser et al., 2022; Rao et al., 2000).

These studies emphasize the need for schools to account for the cultural differences between school and home for parents of color to feel empowered to take part and advocate for their children. Morgan and Stahmer (2021) conducted in-depth interviews with single Black mothers to investigate the types of cultural capital Black mothers used to navigate special education systems for their children on the autism spectrum. Instead of highlighting the deficits of Black parents, Morgan and Stahmer used a critical race theory framework to understand the assets, such as community cultural wealth, that Black parents brought to the IEP tables. Community cultural wealth can be described as the unrecognized internal resources and assets that communities of color use to survive in hostile, anti-Black, and discriminatory environments. Yosso (2005) expanded on the concept, identifying six types of cultural capital that communities of color possess: Aspirational, familial, linguistic, social, navigational, and resistance capitals. Morgan and Stahmer included these and two other capitals, Motherhood Capital (Lo, 2016) and Black Cultural Capital (Carter, 2003) to investigate if and how five Black single mothers were using their existing capital to navigate interactions with their children’s intervention team. Not only did these mothers possess substantial capital, but they extensively exercised two—Navigational and Resistance capital—to advocate for their children. Results indicated that when schools used family-centered practices, such as providing space for families to ask questions and have meaningful input during IEP team meetings, Black mothers better activated their advocacy resources. Both Wilson (2015) and Morgan and Stahmer give evidence that context is key to Black parent advocacy being effective when interacting with service delivery agencies (i.e., schools, medical institutions, therapy centers, etc.) and that when agencies work to create climates that acknowledge and address intersectional barriers of Black disabled children that families can be more effectively engaged.

Systemic Racism in Service Delivery Systems Causes Harm

School and medical systems are composed of thousands of providers that come into the professions to help and heal the people they serve but because of structural racism, these same people may become agents of harm for Black families and children. According to the annual report to Congress on implementing IDEA 2004, Black, Native American, and Asian children are nationally under-represented in early intervention (Part C) programs (Office of Special Education Programs [OSEP], 2019). These disparities may arise because Black families are more likely to live in low-income households and have a lower quality of health care, thereby limiting developmental screening and monitoring by a medical/health professional and reducing access to early intervention (Aber et al., 1997; Burkett et al., 2015; Longtin & Principe, 2014). Black families are less likely to experience early intervention services for their children; therefore, they miss the family-centered goals and naturalistic treatment and parental involvement inherent during (0-3, Part C) early intervention (Harry, 2008). Integrating parents and home environment into treatment are crucial elements of early intervention, which creates opportunities for parents to understand their role, significance, and power on the intervention team. When children are diagnosed after 3 years old, they and their families miss the early intervention (Part C) experience that, therefore, reduces their understanding, knowledge, and social networks because family services are not mandated in the same way once children enter school (Part B). For Black children who are often diagnosed after 4 years old, this can further marginalize them from accessing services and supports because their families are not as knowledgeable and socially connected as they would be if they were involved in early intervention for their children (Eyal, 2013; Lareau, 1987; Lareau & Horvat, 1999; Lareau & Weininger, 2003; Trainor, 2010).

Provider Bias Causing Harm

There is an abundance of literature about the effects of providers’ attitudes toward race on interactions with families and clinical practice (Chapman et al., 2013; Johnson, 2020; Neitzel, 2018). These attitudes can manifest themselves in explicit (overt) and implicit (covert) biases that impact the interactions and communication providers have with patients, students, and clients. A study conducted by Green et al. (2007) found that the physician’s unconscious and implicit racial bias influenced racial/ethnic disparities in healthcare. Using questionnaires found within the Implicit Association Test (IAT), this group of Harvard researchers found that although the physicians reported no explicit preference for White vs. Black patients when asked about differences in how they perceived patient cooperativeness, the IAT revealed an implicit preference for White patients. Therefore, researchers posited an increased likelihood that physicians would refer White patients for proper tests and treatment for coronary heart disease more often than Black patients because of perceptions that they would more likely comply with recommendations. The role of implicit bias on access to diagnostic testing and treatment for Black children has been substantiated in empirical investigations (Morgan & Stahmer, 2021, Stahmer et al., 2019; Straiton & Sridhar, 2022 ) and may explain some of the late and misdiagnoses described in the literature.

Families who have children with autism often face challenges when engaging with providers in healthcare settings and feel stigmatized (Farrugia, 2009; Kinnear et al., 2016; Pearson & Meadan, 2018). Factors that may contribute to this stigmatization and marginalization include but are not limited to challenges with access to care (Tregnago & Cheak-Zamora, 2012), difficulty finding healthcare providers (Chiri & Warfield, 2012), and financial hardships caused by out-of-pocket expenses (Tregnago & Cheak-Zamora, 2012). Healthcare providers influence the provider-patient encounters with how they speak to and about the families they work with. Because of this, it is imperative that providers are aware of their unconscious bias and use self-reflection when considering their rhetoric and language use when describing marginalized groups they serve (Como et al., 2019). Como et al. conducted a qualitative study to investigate the unconscious biases that health care providers have toward their autistic clients. They found that the providers biases were often expressed in their language. They conducted two 3-hour focus groups of seven dental professionals who had at least 1 year of experience treating autistic children. Semistructured questions were asked to the small groups of dental care providers and thematic analysis was utilized to code the transcripts (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). The study found that healthcare providers indeed engaged in microaggressions, marginalization, and preconceptions of their autistic patients and their families. Even with cultural competence being promoted in the healthcare system, this study illustrated that there is still more work to be done to address the implicit and unconscious bias held by healthcare providers working with families with children with autism, especially those from marginalized backgrounds like Black families.

Agents of Healing: UCEDD Programs to Support Black Autistic Children and Their Families

The U.S. government funds 67 federally designated university centers (UCEDDs) across the country. These centers are authorized by the Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act and funded by the Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AIDD), part of the Administration on Community Living within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This section describes the programmatic efforts of two UCEDDs to support Black Autistic children and their families.

The UC Davis UCEDD, established in 2006, serves as a resource in the areas of education, research, and service, and provides a link between the university and the community to improve the quality of life for individuals with developmental disabilities. The mission of the UCEDD is to collaborate with individuals with developmental disabilities and their families to improve quality of life and community inclusion. The Center accomplishes this mission through advocacy, community partnerships, interdisciplinary training, and the translation of research into practical applications. UCEDD uses an implementation science framework, which includes a focus on community partnered participatory research (CPPR) to ensure research is relevant to the community and includes participation by historically underserved populations. CPPR emphasizes equal power sharing, knowledge exchange and authentic partnership between academic and community members and aims to create culturally responsive and sustainable solutions to real-world challenges (Jones, 2018; Jones & Wells, 2007).

The UCEDD has partnered with cultural brokers to form the parent support group named Sankofa. We founded Sankofa in 2015 in order to meet the unique needs of parents of Black children with autism and other developmental disabilities. The word Sankofa is a Twi/F anteword that comes from the Akan cultural community of present-day Ghana and means “go back and fetch it” or “to retrieve” (Temple, 2010), which is significant to the mission and purpose of the group: taking information and resources we learn back to people in our Black Developmentally Disabled community members. Since its inception, Sankofa has supported the needs of over 200 families in the greater Sacramento area, and since going virtual during the pandemic has served hundreds more globally. Through providing culturally sensitive and relevant resources, Sankofa seeks to provide information that increased awareness of developmental disabilities and supports the growth of self-advocacy for the Black disabled community and their families. Sankofa is Northern California’s only parent support group solely for Black families impacted by developmental disability (ASD/DD) within a 364 radius of UC Davis. We believe that because of the aforementioned data of disparities in early diagnosis and access to evidence-based treatment (Gourdine & Algood, 2014; Longtin & Principe, 2014; Mandell et al., 2002, 2009), groups like Sankofa are critical in addressing the public health issues of inadequate treatment for our Black ASD/DD community.

Sankofa meets monthly to provide high-quality, culturally competent training and discussions about disability and advocacy related topics for Black families and providers. Topics of discussion include but are not limited to: Parental Rights under IDEA Part B and C, Understanding Behavioral Intervention Plans, Promoting Self-Determination and Alternatives to Conservatorship for Disabled People, Dealing with Generational Trauma, The Role of Intersectionality in Black Parent Interactions with Providers, Stigma of Disability in the Black Community, Prioritizing Self-Care, and Mental Health Supports for Caregivers. Besides meetings, Sankofa group parent and provider leaders have conducted outreach events in neighboring Black churches and community organizations to promote disability awareness and inclusion around the greater Sacramento area. Sankofa provided a range of outreach efforts through our UCEDD including hosting monthly support and information meetings, providing culturally relevant and sensitive trainings, engaging in strategic outreach to historically under-resourced communities, to provide space for intentional, purposeful planning and networking for Black families and eradicating stigma associated with disability in the Black community to promote inclusion. The group facilitators, Elizabeth Morgan, Benita Shaw, and Jazmin Burns are all Black mothers, advocates, and providers that believe in the value of centralizing the lived experiences of disabled Black children and their families to spread awareness and promote advocacy within their community. They have integrated mental health resources specific to the Black community into the fabric of Sankofa and making peer to peer mentoring a central aspect of their engagement with families. The Sankofa facilitators are also currently working toward replicating Sankofa groups in other states and rural communities to have a greater impact and unifying reach to BIPOC families of disabled children around the country and globe.

The Waisman Center UCEDD, located at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, utilizes a Community of Solutions Framework (Stout, 2017; Weinstein et al., 2017) to partner with family leaders from a range of socially and economically marginalized communities. A core tenet of this framework is that “people with lived experience of inequity work together with community connectors and resource stewards to co-design and drive change” (Stout, 2017, p. 20). The UCEDD launched its first community of solutions project in 2018 as part of the UCEDD’s Wisconsin Care Integration Initiative (WiCII). This project activated a partnership between rural community and other stakeholders to co-create solutions to barriers to services and supports for children with autism in rural southwestern Wisconsin. Building on that experience, in 2020 the UCEDD began convening family leaders for a monthly meeting that serves as an incubator for leadership development and community solutions initiatives. The incubator currently brings together seven parent leaders who identify as Black, Latinx, rural, LGBTQ+, or as having a disability themselves. One tangible outcome of this effort was that a Latino family leader secured Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) funding for a Community Solutions for Health Equity project co-directed by the family leader and a UCEDD staff member (the seventh author of this manuscript). This 3-year initiative (2021-2024) aims to elevate the voices of Latinx community members raising children with developmental disabilities and to support community and health care stakeholders to co-create health equity solutions. This initiative is channeling $300,000 in funding directly to the parent-led non-profit Padres e Hijos en Acción.

Black members of the incubator are providing leadership to understand and respond to the unique needs of the Black community. Through interviews and listening sessions with parents and professionals, Ida Winters and Chiffon King are identifying Black families’ experiences, barriers to health equity, and strategies that might drive effective change. Black families of children with autism or other developmental disabilities in Wisconsin want and need to be treated with dignity and respect, to receive information from people they trust, and to be recognized for their own wisdom and leadership. They identified the Sankofa model developed at the UC Davis UCEDD as one promising practice to meet these needs. Black family leaders are leading the way to adapting this model for implementation in Wisconsin, and the CEDD is partnering to provide supports. Importantly, Black family leaders guide the level and type of support provided, with UCEDD partners sharing information about the support they can offer.

Although one measure of success of these types of programs is their impact on disparities in timely access to high quality services and support, an equally critical measure of success is how these programs affect the self-efficacy, leadership, and self-determination of Black and other minoritized family members of autistic children.

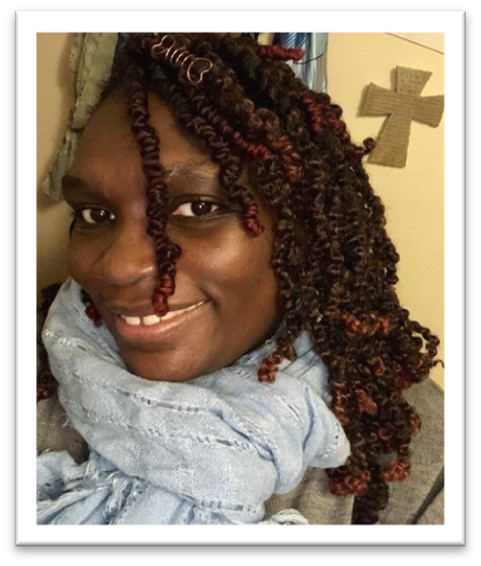

Meet the Partners

In this next section, we highlight our partners, Black mother parent advocates who have joined forces with our UCEDDs to create meaningful programs to support Black families and children with developmental disabilities. Hear their stories of forming their advocate identities and how to use their experiences to help develop programming as partners in our UCEDDs Black communities in California and Wisconsin. These stories help give insight to the significance of partnering with members within marginalized communities to create programs that meet the needs of the families we serve.

Benita Shaw: Creating Paths to Equity for Black Families at the UC Davis UCEDD at the MIND Institute

I have always felt that I had to go over and beyond when advocating for my son Christopher because I felt doctors and teachers did not take me seriously. It never failed that whenever I questioned or challenged people on my son’s care team, they looked shocked saying “wow,” like they didn’t expect me to know my rights or have insight into how to help my child. Now I know to expect this type of treatment, but at first it was humiliating and dehumanizing. Now, I make sure they realize I’m serious. I’m 100% serious about getting proper support for my child and I will hold them accountable for doing their job, because they will hold me accountable as being my son’s parent. I do not believe that I would have gotten this far and gotten Christopher the multiple services he has had over the years if it would not have been for me doing everything in my power to be taken seriously. It has felt like I had six or seven jobs at some points, but it has all been worth it.

One time that sticks out in my mind started with a call from my son’s middle school classroom teacher. The teacher would call every day complaining of my son’s behaviors. So much so that every time the phone rang, I would get a pit in my stomach. His teacher would often call me and ask me to pick Christopher up from school. They never wanted to document that he was leaving because of behaviors but just wanted me to pick him up. They were basically suspending him but with no paper trail, so it looked like they were not violating his Behavioral Intervention Plan (BIP) in his IEP. On this day I didn’t feel like fighting, and I didn’t want my child to be in an environment where he was not wanted so I came and picked him up. When I got to the school, he was in a classroom surrounded by school security monitors all by himself because they had evacuated all the other students. Interestingly all of the monitors that they had surround him were Black. There was one guy standing in a police stance at the door blocking my nonspeaking autistic son Christopher in the room. The scene looked like a prison movie with the correction officers rallying to control a prisoner, but this was not a movie. This was real life, and this was not a prisoner. This was my son. I knew I could not let this happen to my child, so I went to work. I think that year I must have had about six or seven IEPs. To the point one principal said to me, “I have never in my life seen such a thing.” My son was in a position that he was in danger, being pushed into a corner and when he went into flight or fight mode, the school just escalated the situation. Nobody acknowledged he was autistic, nor gave him a way to communicate his frustrations and, as a result, they had no means to deescalate the situation. The truth is, they saw my son, his tall and broad stature, and saw him as a threat and menace to their classroom and wanted him out. From that day forward I became even more active in the advocacy for my son. I was always the one to take him and drop him off at school because I felt that was important because they need to know without a shadow of a doubt this Black mother was present and active. I wanted them to know that when they heard the name Christopher, that they would also see a momma bear coming behind him to advocate for him. I could be a pleasant bear or a fierce bear. It was up to them and how they treated my son while he was in their care. And it took a lot out of me, but I do it again.

I helped to start the Sankofa group because I believe, as people of color, we struggle with navigating schools and medical systems differently. Daily we have to fight to survive in a society that hates us just for being Black and having darker skin and melaninated pigmentation. We are already judged and stereotyped as soon as we walk into a room. So, add in other marginalized identities, like being single, I am a single mom. There is a stigma with that everywhere I go, being a single Black mother. Or having children that have disabilities. I have found these are common issues that Black families express during our Sankofa support group meetings. The bottom line is that everyone wants their children to have choices and opportunities but when you are a Black family of children with developmental disabilities, it’s like trying to swim through molasses with all these different labels and limitations based on your family’s multiply marginalized identities. Black Families know that they have to get through systemic racism, classism, sexism, and ableism in order to get what they need for their loved one but having to do it all alone feels impossible. Which is why Sankofa, and groups like Sankofa, are so important. Staying true to the meaning of Sankofa (go back and fetch it), I have found that it is very important to reach back to help other families in my community because I know that their child’s success is also success for me and our community. Sankofa is a space for Black families of children with various disabilities to come and meet other families, get mentored, learn skills, and be vulnerable with people they can trust. Finding a person who we can connect with to guide us through this journey is so valuable and that is what we do at Sankofa. We are constantly exchanging information and tips with one another to live out the motto of the National Association of Colored Women “lift as we climb.” Because to me, knowledge is power and programs like Sankofa can be a crucial element in producing equitable service delivery systems for children of color.

Ida Winters: Creating Paths to Equity for Black Families at the Waisman Center UCEDD

They diagnosed my son with ADHD, ODD, OCD, and psychosis at 3 years old while only being asked a few questions. I was later told by trusted providers “those were heavy diagnoses for a 3-year-old.” While in school, these diagnoses were weaponized and used against him. They did not get him the support that he needed to thrive but kept him isolated and in constant trouble. A Black female principal at one school he attended before receiving an IEP said to me in front of him, she didn’t want him at “her” school and that the school was equipped to provide support for children with disabilities, but not mental and emotional diagnosis like ADHD or Emotionally Disturbed. I noticed that there were lots of White students at the school and they had lots of behavioral issues that were being supported by the staff at the school and even receiving hugs from her. She said that I am going to cause him to be a criminal by not forcing him to make better decisions and disciplining him and emphasizing that “we don’t want him here!” She then moved to have him expelled from the school after a teacher at that school assaulted him and he defended himself. Security tackled him to the floor and carried him out all while he was crying and screaming, “I want my mom,” it was horrific. They put him in the office and just left unattended and the teacher comes to the office and begins yelling and screaming, “you hurt my wrist! You are going to jail!” My son bolts out the front door of the school and they did not even go after him. They told me it is not the school’s responsibility to search for a student who leaves the school.

As a Black parent, I had never heard of a Black child or any person of color having autism. So, giving this school principal the benefit of the doubt, she had not either, but I did my research looking to understand what was going on with my child and how I could help him.

I was told by the school’s principal over the phone not to return him to school until the morning of his Central Office hearing and I said OKAY. The day following this event, I explained this to a therapist that was working with my other son, and she began telling me I had rights and told me that if I did not have a suspension in writing that he was not suspended or required to stay home. I took him in the next day and stated my son has the right to be there, I then proceeded to tell her if she doesn’t want him here, she would have to put it in writing as a suspension. Her response was that she’s trying to save us and suggested that it is not in our best interest to seek a suspension. I demanded that she give me something in writing or he’s staying. I visited the school board about the matter and there was a woman of color working there who advised me on the next steps.

As a family navigator, I am constantly assisting families with issues like these, and it happens more than I’d like to admit. I assist families with navigating the systems, but I believe educating the families is the most important piece. Others in my journey of advocacy gave me small pieces of valuable information to navigate systems throughout my process, but never enough to actually remove barriers. But once I learned the system is like a game and you must know the rules to win, I shared what I knew and who I knew could teach them more.

About 5 years ago I began working on a small project that was a collaboration between the Waisman Center, Maquette University, and Mental Health America WI that was UCEDD-funded, believe it or not that was the very first time that I’ve ever heard of a UCEDD. I was in school full-time as a student, and I was in school part time as a parent all while I was still searching for someone to help me get my son a proper diagnosis and services. I walked into an office at Mental Health America, and they were explaining what the project was about and why these services were important and I stopped them in their tracks right then and there and I politely stated with tears in my eyes “I know.” I began explaining that “this is exactly what I have been going through with my son for years!” You mean to tell me that there is a system or program that wants to assist people with getting Black children and their families with getting a proper evaluation and diagnosis? I couldn’t believe it, then I was immediately offered a screening that took less than 20 minutes and as expected my son had lots of red flags. I actually let tears fall thinking to myself I’m not crazy as the medical professionals and educators implied. I was told that was just the beginning and there was still a long road ahead, but at least now you have something tangible to take with you. With the UCEDD allowing a program like this to be formed (academics, mental health professionals, researchers, educators, and Black parents/community members) having a lot of the right people at the table and hearing what they have to say and working on a plan together to make changes based on the wisdom of the team.

The WiCII project brings together parents/community leaders from different backgrounds from around the state. In this project we were asked, “What matters to you and what’s missing from the community? What are the programs/services in your community? Do you use them, and why or why not?” We were then asked what we wanted/needed to bring to our community and why. Who or what would make it possible to bring this to the community to help fill this void? Support was given by the UCEDD and WiCII project leaders/parents that either went through the process of bringing those missing pieces to their community or were in the process of making those things happen and working towards the same goals. There were no time limits given nor any pressure of what to create. I decided that Milwaukee and Wisconsin needed some kind of social gathering for Black parents and caregivers, and I wanted to bring that, but I wasn’t sure how to make that happen. I was fortunate enough to be connected with Sankofa which is a Social Network for Black parents and caregivers run by Black parent advocates and providers out of University of California Davis. I attended one meeting. It changed my life and I know this is what I am destined to do! Through the UCEDD’s WI LEND program I was able to learn about disabilities, services, interdisciplinary care teams, advocacy, system change, and self-determination, among other things, but what made it so special to me was I learned it right alongside the providers and the future providers. I believe neither of us would’ve gotten this type of experience anywhere else. During this time as a trainee, I found that I was a teacher, a partner, a team member, an ally, and a leader—soon to be a fierce and confident leader. Working as a family navigator at Next Step Clinic in Milwaukee, I am serving, educating, and helping families recognize their own strength. As a WI LEND graduate, I was forced to become a better advocate who is committed to change. I have found that I can be a voice for the voiceless. I now understand that I do belong and should have a seat at the table to advocate for Black families both on the local or national levels. I declare that I belong, and I will not be the meal, but I will be served a meal and not the scraps under the table.

Chiffon King: Creating Paths to Equity for Black Families at the Waisman Center UCEDD

Being a Black woman and raising Black children has empowered me to be more aggressive with serving families of color. I am more intentional about being specific about connecting them to support. I will serve any family, no matter what color they are, but with Black families I know “there are a little more ingredients that go into making that dish” because of daily interactions with racism and them being continuously underserved so that is my motivation to go over and beyond to help them. I have witnessed families of color not given the same opportunities or options as White families. One example comes to mind, when I worked in a school with a diverse student population, I noticed that the White children were receiving more services and teachers had stronger communication with their families as compared to the children of color. When it came to children that looked like me and my family, they were immediately suspended. There wasn’t that same kind of patience and tolerance that White students received given to the students of color and I won’t candy coat it—it was clearly because of racism. There just was not the same level of empathy and compassion demonstrated for Black and Brown students. Families didn’t even know what it was until I’d have the consults with them and let them know “hey, you know, your child’s being disciplined a lot in class. Are you aware of this?” Not only was it an opportunity to get that child services to see what is triggering that behavior, but it was an opportunity number one to build a relationship with another parent of color and number two to educate their family. I knew that if I could educate this one Black mother or father, they could go out and educate three or four more. So, my intention was to create a domino effect. I don’t want to be the only person advocating in the city that I met, because it’s a burden, but it’s a good burden. My school district has one of the highest suspension rates for African American and Hispanic students in the state and so that is another reason I am very vigilant in educating the families about children being sent home consistently when they don’t have the proper supports in place. The schools will suspend or expel students of color at an alarming rate and not even document the suspension or expulsion. That’s when I tell the parents “Oh, well, let’s do a manifestation determination” and then the parents find out there has been no documentations of suspensions—that violates that child’s rights to a Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE). These experiences drive me to advocate for Black families unapologetically and boldly. Someone must speak life into that parent and to speak life into their child, because the schools and systems will be relentless in disenfranchising them and tear them down. They must know that their child is not their suspension, and they are not their behavior. They are a Black child with a disability and deserve access and inclusion just like every other child in their schools.

I know that the peer coaching that our UCEDD is providing for Black families in Wisconsin is making a difference. An example occurred recently, I was able to call a parent who was on the referral list and asked her if she is still interested in receiving services. I was very apologetic about them being put on the waiting list and she’s like, “Oh, no, my daughter was actually already tested at another location and now has an autism diagnosis.” I ask, “Well, can you tell me what services that she’s being given” and she’s like, “well, she only gets this” and I am like, “Well, are you aware that there are other types of interventions that might be a good fit” and she is like, “No, I never heard of that.” I have found a disconnected for Black families after they finally receive a diagnosis of autism for their children and that they rarely have information or people that can support them in securing the appropriate intervention to fit their child’s individual needs. I asked her if she is comfortable with me connecting her to support and sending her monthly resources. I also asked if she was ok with me calling her back and checking in with her once a month to see how things were going. She was so excited, saying, “Oh my gosh, you are a blessing. Thank you so much! I would love to be connected.” Exclaiming that she felt relieved that she had me as a resource and was even more appreciative that I am a Black mother of children with developmental disabilities because I can understand her better. Not that no one else can help her, it is just that there are cultural differences for Black families that are hard to understand unless you are a part of the community. Which is why I believe that culturally sensitive peer to peer navigators can be especially helpful for Black families soon after a diagnosis—especially while they wait on services to begin.

I saw this even when I worked in schools, I receive referrals from the school psychologist and the social worker, and they will call me and say, “this family has identified with this, but they’re not open to me or they’re giving me a hard time,” so they asked me to reach out to the family, and I will get a completely different response. We must recognize that people in many Black communities have dealt with inequities in so many areas for so many years, and this has led to a lack of trust in educational and medical providers. It is necessary to know the history and look at the bigger picture because most of the time they are not rejecting the person they are protecting themselves from the institutions. Black people have been through trauma. Black people have been wrongfully judged or treated according to the pigment and melanin in their skin by systems deeply rooted in White supremacy. Which is why when they see a person who looks like them, talks like them, and understands their history, they are more likely to be comfortable with me. I am happy about the skin that I am in because I have been able to serve so many families because I am a Black woman. Because I am a Black woman who has two children with disabilities, I have gone through some of the same experiences as they have or either will encounter, so that really gives them hope and confidence that they can do it too. I am proud that our Wisconsin UCEDD has programs like this to support our Black families. I am proud of the work we are doing.

Recommendations

There is a growing need for healthcare and education systems to improve care for the disability community. This population makes up 19% of the U.S. and many individuals face significant healthcare disparities and barriers to accessing healthcare services (Iezzoni, 2011). When disability is joined with other intersectional marginalized identities (e.g., race, gender, etc.) compared to nondisabled individuals there is a need for intentional programming to better support our multi-marginalized communities. This includes training on providing culturally competent, family-centered care (Crossley, 2015; Morgan & Stahmer, 2021) but also by providing safe spaces, such as support groups like Sankofa, to offer family navigation and peer-coaching. Care providers need to be intentional about engaging and partnering with Black families to build and foster their agency and activism for their children, therein by increasing their self-esteem and resilience to endure the hard journey of advocacy ahead of them. We also need to have training for providers who work with Black families on how to provide family-centered and culturally competent care. Last, we need to make sure that White providers know not to come into Black communities with “White Savior” mentalities but with humility and willingness to learn about the individual needs of the families and child.

Conclusion

Even though there have been strides and attempts to include Black voices in the disability community advocacy movement, there is still a long way to go. Providers need to continue to reflect on their implicit biases and how these biases can negatively impact their work with Black families. There are important steps that need to be taken to improve the care that Black families receive. One step is for health care providers and community members to work towards reducing the stigma that surrounds mental health and neurodevelopmental disabilities within the Black population (Kinnear et al., 2016). A second important step is to conduct more qualitative research about the lived experiences that Black families have in receiving diagnoses, as well as supports and services for their children (Harry & Ocasio-Stoutenburg, 2021). Third, Black families need to be empowered to exercise their voices in research, policy, and practice arenas (Morgan & Stahmer, 2021). Fourth, providers should learn to become aware of any implicit biases that may impact their work with Black families and other families of color. By making training mandatory for topics such as cultural competence and family-centered planning, providers will be able to provide care in a way that is humble, caring, and decreases the power differential between themselves and their patients. Last, to boost Black families’ self-esteem and resilience, they should be made aware of support groups, such as Sankofa, peer coaching opportunities, and family navigation programs. The work and testimonies of our co-authors and partners gives evidence that navigating service delivery systems such as schooling and healthcare systems to get appropriate services for their children can be exhausting. Therefore, we stress that the onus and obligation of providing culturally competent care needed has to be placed on the shoulders of providers and organizations. We hope that these examples of partnership and intentionality will inspire other UCEDDs and service providers to engage in similar programming and practice to help create pathways for equity for all families of children with disabilities.

References

Aber, J. L., Bennett, N. G., Conley, D. C., & Li, J. (1997). The effects of poverty on child health and development. Annual Review of Public Health, 18(1), 463–483. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev. publhealth.18.1.463

Angell, A. M., & Solomon, O. (2014). The social life of health records: Understanding families’ experiences of autism. Social Science & Medicine, 117, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014. 07.020

Arunyanart, W., Fenick, A., Ukritchon, S., Imjaijitt, W., Northrup, V., & Weitzman, C. (2012). Developmental and autism screening. Infants & Young Children, 25(3), 175–187. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/iyc.0b013e31825a5a42

Baio, J., Wiggins, L., Christensen, D. L., Maenner, M. J., Daniels, J., Warren, Z., Kurzius-Spencer, M., Zahorodny, W., Robinson Rosenberg, C., White, T., Durkin, M. S., Imm, P., Nikolaou, L., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Lee, L.-C., Harrington, R., Lopez, M., Fitzgerald, R. T., Hewitt, A., … Dowling, N. F. (2018). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(6), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1

Behrens, S., Dean, E., & Torres, M. (2022). Family perspectives on developmental monitoring: A qualitative study. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 2(2), 83-103. https://digitalcommons.usu. edu/ddnj/vol2/iss2/8/

Bhattacharya, K. (2020). Understanding entangled relationships between un/interrogated privileges: Tracing research pathways with contemplative art-making, duoethnography, and Pecha Kucha. Cultural Studies↔ Critical Methodologies, 20(1), 75-85.

Borunda, R., Joo, H., Mahr, M., Moreno, J., Murray, A., Park, S., & Scarton, C. (2020). Integrating “White” America through the erosion of White supremacy: Promoting an inclusive humanist White identity in the United States. Critical Questions in Education, 11(1), 38-56.

Broder-Fingert, S., Shui, A., Pulcini, C. D., Kurowski, D., & Perrin, J. M. (2013). Racial and ethnic differences in subspecialty service use by children with autism. Pediatrics, 132(1), 94-100. https://doi.org/ 10.1542/peds.2012-3886

Brown, H. (2015). Still learning after three studies: From epistemology to ontology. International Review of Qualitative Research, 8(1), 127-143.

Burkett, K., Morris, E., Manning-Courtney, P., & Shambley-Ebron, J. A. D. (2015). African American families on autism diagnosis and treatment: The influence of culture. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(10), 3244–3254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2482-x

Carter, P. L. (2003). “Black” cultural capital, status positioning, and schooling conflicts for low-income African American youth. Social Problems, 50(1), 136-155.

Chapman, E. N., Kaatz, A., & Carnes, M. (2013). Physicians and implicit bias: How doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(11), 1504–1510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1

Chiri, G., & Warfield, M. E. (2012). Unmet need and problems accessing core health care services for children with autism spectrum disorder. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(5), 1081-1091.

Como, D. H., Floríndez, L. I., Tran, C. F., Cermak, S. A., & Stein Duker, L. I. (2019). Examining unconscious bias embedded in provider language regarding children with autism. Nursing & Health Sciences, 22(2), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12617

Constantino, J. N., Abbacchi, A. M., Saulnier, C., Klaiman, C., Mandell, D. S., Zhang, Y., Hawks, Z., Bates, J., Klin, A., Shattuck, P., Molholm, S., Fitzgerald, R., Roux, A., Lowe, J. K., & Geschwind, D. H. (2020). Timing of the diagnosis of autism in African American children. Pediatrics, 146(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3629

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1, 139–167.

Crossley, M. (2015). Disability cultural competence in the medical profession. Saint Louis University Journal of Health Law & Policy, 9(1), 89-110.

Daniels, A. M., & Mandell, D. S. (2013). Explaining differences in age at autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: A critical review. Autism, 18(5), 583–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313480277

De Wolfe, J. (2016). Parents of children with autism: An ethnography. Palgrave Macmillan.

Dumas, M. J., & ross, k. m. (2016). “Be real Black for me”: Imagining BlackCrit in education. Urban Education, 51(4), 415-442.

Eyal, G. (2013). For a sociology of expertise: The social origins of the autism epidemic. American Journal of Sociology, 118(4), 863–907. https://doi.org/10.1086/668448

Farrugia, D. (2009). Exploring stigma: Medical knowledge and the stigmatisation of parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Sociology of Health & Illness, 31(7), 1011–1027. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01174.x

Fish, R. E. (2019). Standing out and sorting in: Exploring the role of racial composition in racial disparities in special education. American Educational Research Journal, 56(6), 2573–2608. https://doi.org/ 10.3102/0002831219847966

Gourdine, R. M., & Algood, C. L. (2014). Autism in the African American population. In V. D. Patel, V. R. Preedy, & C. R. Martin, C. R. (Eds.), Comprehensive guide to autism (pp. 2455-2467). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4788-7_155

Gourdine, R. M., Baffour, T. D., & Teasley, M. (2011). Autism and the African American community. Social Work in Public Health, 26(4), 454–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2011.579499

Gopaldas, A. (2013). Intersectionality 101. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 32(1_suppl), 90–94. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.12.044

Green, A. R., Carney, D. R., Pallin, D. J., Ngo, L. H., Raymond, K. L., Iezzoni, L. I., & Banaji, M. R. (2007). Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for Black and White patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(9), 1231–1238. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11606-007-0258-5

Grinker, R. R. (2008). Unstrange minds: Remapping the world of autism. Basic Books.

Harris, J. C., & Patton, L. D. (2018). UN/doing intersectionality through higher education research. The Journal of Higher Education, 90(3), 347–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1536936

Harry, B. (2002). Trends and issues in serving culturally diverse families of children with disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 36(3), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224669020360030301

Harry, B. (2008). Collaboration with culturally and linguistically diverse families: Ideal versus reality. Exceptional Children, 74(3), 372–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290807400306

Harry, B., & Ocasio-Stoutenburg, L. (2021). Parent advocacy for lives that matter. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 46(3), 184–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/15407969211 036442

Harstad, E., Huntington, N., Bacic, J., & Barbaresi, W. (2013). Disparity of care for children with parent-reported autism spectrum disorders. Academic Pediatrics, 13(4), 334–339. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.acap.2013.03.010

Hassrick, E. M. (2019). Mapping social capital for autism. In S. B. Sheldon & T. A. Turner-Vorbeck (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of family, school, and community relationships in education (pp. 91-115). Wiley-Blackwell.

Hernández, T. (2015). Colorism and the law in Latin America global perspectives on colorism conference remarks. Washington University Global Studies Law Review, 14(4), 683-694.

hooks, b. (1996). Killing rage: Ending racism. Henry Holt and Company, Inc.

hooks, b., (2014). Ain’t I a woman: Black women and feminism. Routledge.

Iezzoni L. I. (2011). Eliminating health and health care disparities among the growing population of people with disabilities. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 30(10), 1947–1954. https://doi.org/10.1377/ hlthaff.2011.0613

Johnson, T. J. (2020). Racial bias and its impact on children and adolescents. Pediatric Clinics, 67(2), 425-536.

Jones L. (2018). Commentary: 25 years of community partnered participatory research. Ethnicity & Disease, 28(Suppl 2), 291–294. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.28.S2.291

Jones, L., & Wells, K. (2007). Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(4), 407-410. doi:10.1001/ jama.297.4.407

Kaiser, K., Villalobos, M. E., Locke, J., Iruka, I. U., Proctor, C., & Boyd, B. (2022). A culturally grounded autism parent training program with Black parents. Autism, 26(3), 716-726. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/13623613211073373

Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2(3), 217-250.

Kinnear, S. H., Link, B. G., Ballan, M. S., & Fischbach, R. L. (2016). Understanding the experience of stigma for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder and the role stigma plays in families’ lives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(3), 942–953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2637-9

Lareau, A. (1987). Social class differences in family-school relationships: The importance of cultural capital. Sociology of Education, 60(2), 73-85.

Lareau, A., & Horvat, E. M. (1999). Moments of social inclusion and exclusion: Race, class and cultural capital in family-school relationships. Sociology of Education, 72(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/2673185

Lareau, A., & Weininger, E. B. (2003). Cultural capital in educational research: A critical assessment. Theory and Society, 32, 567–606. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RYSO.0000004951.04408.b0

Lo, M. C. M. (2016). Cultural capital, motherhood capital, and low-income immigrant mothers’ institutional negotiations. Sociological Perspectives, 59(3), 694-713.

Locke, J., Kang-Yi, C. D., Pellecchia, M., Marcus, S., Hadley, T., & Mandell, D. S. (2017). Ethnic disparities in school-based behavioral health service use for children with psychiatric disorders. The Journal of School Health, 87(1), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12469

Longtin, S. E., & Principe, G. M. (2014). The relationship between poverty level and urban African American parents’ awareness of evidence-based interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders: Preliminary data. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31(2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357614522293

Lovelace, T. S., Robertson, R. E., & Tamayo, S. (2018). Experiences of African American mothers of sons with autism spectrum disorder: Lessons for improving service delivery. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 53, 3–16.

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Esler, A., Furnier, S. M., Hallas, L., Hall-Lande, J., Hudson, A., Hughes, M. M., Patrick, M., Pierce, K., Poynter, J. N., Salinas, A., Shenouda, J., Vehorn, A., Warren, Z., Constantino, J. N., … Cogswell, M. E. (2021). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 70(11), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1

Mandell, D. S., Ittenbach, R. F., Levy, S. E., Pinto-Martin, J. A. (2007). Disparities in diagnoses received prior to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 37, 1795–1802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0314-8

Mandell, D. S., Listerud, J., Levy, S. E., & Pinto-Martin, J. A. (2002). Race differences in the age at diagnosis among Medicaid-eligible children with autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 1447–1453.

Mandell, D. S., Wiggins, L. D., Carpenter, L. A., Daniels, J., DiGuiseppi, C., Durkin, M. S., Giarelli, E., Morrier, M. J., Nicholas, J. S., Pinto-Martin, J. A., Shattuck, P. T., Thomas, K. C., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., & Kirby, R. S. (2009). Racial/ethnic disparities in the identification of children with autism spectrum disorders. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 493-498, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007. 131243

Morgan, E. H., Rodgers, R., & Tschida, J. (2022). Addressing the intersectionality of race and disability to improve autism care. Pediatrics, 149(Supplement 4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-049437M

Morgan, E. H., & Stahmer, A. C. (2021). Narratives of single, Black mothers using cultural capital to access autism interventions in schools. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 42(1), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2020.1861927

Neitzel, J. (2018). Research to practice: Understanding the role of implicit bias in early childhood disciplinary practices. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 39(3), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2018.1463322

Ocasio-Stoutenburg, L. (2021). Becoming, belonging, and the fear of everything Black: autoethnography of a minority-mother-scholar-advocate and the movement toward justice. Race Ethnicity and Education, 24(5), 607-622.

Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP). (2019). Child find self-assessment best practices list. U.S. Department of Education. https://osep.grads360.org/#communities/pdc/documents/17959

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2015). Racial formation in the United States. Routledge.

Pearson, J. N., & Meadan, H. (2018). African American parents’ perceptions of diagnosis and services for children with autism. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 53(1), 17-32.

Pearson, J. N., & Meadan, H. (2021). Faces: An advocacy intervention for African American parents of children with autism. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 59(2), 155–171. https://doi.org/ 10.1352/1934-9556-59.2.155

Rao, S. S. (2000). Perspectives of an African American mother on parent–professional relationships in special education. Mental Retardation, 38(6), 475-488.

Rozsa, M. (2016, October 12). Gender stereotypes have made us horrible at recognizing autism in women and girls. Quartz. https://qz.com/804204/asd-in-girls-gender-stereotypes-have-made-us-horrible-at-recognizing-autism-in-women-and-girls/

Ryan, S., & Runswick-Cole, K. (2009). From advocate to activist? Mapping the experiences of mothers of children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22, 43–53.

Sawyer, R. D., & Norris, J. (2012). Duoethnography. Oxford University Press

Shaw, A. K., Accolla, C., Chacón, J. M., Mueller, T. L., Vaugeois, M., Yang, Y., Sekar, N., & Stanton, D. E. (2021). Differential retention contributes to racial/ethnic disparity in U.S. academia. PLOS One, 16(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259710

Silverman, C. (2011). Understanding autism: Parents, doctors, and the history of a disorder. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stanley, S. L. G. (2015). The advocacy efforts of African American mothers of children with disabilities in rural special education: Considerations for school professionals. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 34(4), 3-17.

Stout, S. (2017). Overview of SCALE and a community of solutions. SCALE 1.0 synthesis reports. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. https://www.ctc-ri.org/sites/default/files/uploads/4%20-%20 SCALE-Community-of-Solutions.pdf

Stahmer, A. C., Vejnoska, S., Iadarola, S., Straiton, D., Segovia, F. R., Luelmo, P., Morgan, E.H, Lee S.H., Javed, A., Bronstein, B., Hochheimer, S., Cho, E., Aranbarri, A., Mandell, D., Hassrick, E., Smith, T., Kasari, C. (2019). Caregiver voices: Cross-cultural input on improving access to autism services. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00575-y

Straiton, D., & Sridhar, A. (2022). Short report: Call to action for autism clinicians in response to anti-Black racism. Autism, 26(4), 988–994. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211043643

Sullivan, A. L. (2013). School-based autism identification: Prevalence, racial disparities, and systemic correlates. School Psychology Review, 42, 298–316.

Thomas, K. C., Ellis, A. R., McLaurin, C., Daniels, J., & Morrissey, J. P. (2007). Access to care for autism-related services. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(10), 1902-1912. doi:10.1007/ s10803-006-0323-7

Trainor, A. A. (2010). Reexamining the promise of parent participation in special education: Analysis of cultural and social capital. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 41(3), 245-263.

Temple, C. N. (2010). The emergence of Sankofa practice in the United States: A modern history. Journal of Black Studies, 41(1), 127-150.

Tregnago, M. K., & Cheak-Zamora, N. C. (2012). Systematic review of disparities in health care for individuals with autism spectrum disorders in the United States. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(3), 1023–1031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.01.005

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15, 398–405.

Weinstein, J. N., Geller, A., Negussie, Y., & Baciu, A. (2017). Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. The National Academies Press.

West, C. (2018). Race matters. In Color class identity (pp. 169-178). Routledge.

Wiggins, L. D., Durkin, M., Esler, A., Lee, L. C., Zahorodny, W., Rice, C., Yeargin‐Allsopp, M., Dowling, N. F., Hall‐Lande, J., Morrier, M. J., Christensen, D., Shenouda, J., & Baio, J. (2019). Disparities in documented diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder based on demographic, individual, and service factors. Autism Research, 13(3), 464–473. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2255

Wilson, N. M., (2015). Question-asking and advocacy by African American parents at Individualized Education Program meetings: A social and cultural capital perspective, Multiple Voices for Ethnically Diverse Exceptional Learners, 15(2), 36–49.

Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Rice, C., Karapurkar, T., Doernberg, N., Boyle, C., & Murphy, C. (2003). Prevalence of autism in a U.S. metropolitan area. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.1.49

Yingling, M. E., & Bell, B. A. (2018). Racial-ethnic and neighborhood inequities in age of treatment receipt among a national sample of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 23(4), 963–970. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318791816

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69-91.