9 Beyond Representation: Partnerships, Intersectionality, and the Centering of the Disability, Family, and Community Lived Experience

Lydia Ocasio-Stoutenburg; Julieta Hernandez; and Douglene Jackson

Ocasio-Stoutenburg, Lydia PhD; Hernandez, Julieta PhD, LCSW; and Jackson, Douglene PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA (2023) “Beyond Representation: Partnerships, Intersectionality, and the Centering of the Disability, Family, and Community Lived Experience,” Developmental Disabilities Network Journal: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 10.

Plain Language Summary

COVID-19 highlighted health disparities that existed in Black, Latino, and disability communities. In response, institutions galvanized efforts toward diversity, equity, and inclusion (EDI). Our center serves families of children with disabilities and complex health care needs. It is in a diverse southeastern United States multicultural community. The center developed responsive strategies to address disparities and access to services.

We created the 5R Method as a tool to analyze these responses. The 5 Rs are: reflect, review, represent, revise, and respond. We assessed our internal and external EDI efforts, including community-academic partnerships. Also, we evaluated how the center included lived experiences and amplified diverse voices.

We recognize our positionality and call for individual and organizational reflective practices. The findings revealed the need for authentic community engagement and equitable action plans. Intersectionality, including disability, must be a part of institution’s EDI initiatives. Strategic actions should be responsive and empower the community.

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced a public health crisis, overlaying the disparities in healthcare access, treatment, and outcomes that were already prevalent in Black and Latino communities across the U.S., particularly persons with disabilities (PWD) at the intersection of racial and ethnic identities. In addition, the concurrent social and political climate mirrored the pandemic in its action of magnifying existing systemic inequities for historically marginalized populations, calling for institutions to galvanize efforts toward diversity, equity, and inclusion (EDI). Our University Center on Excellence in Disabilities (UCEDD) serves a range of families whose children have disabilities or complex health care needs and strengths within a widely diverse cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic region of the southeastern U.S. We have also committed to professional development of diverse faculty, community providers, and inclusive leadership pipeline programs across multiple disciplines.

While our existing efforts have had an impact prior to the pandemic, gaps in information about COVID-19, limited access to needed supports, vacillations in services, and disruptions to family- and community-life have called for us to develop more responsive strategies. We discuss the development and implementation of new interprofessional and inclusive community approaches, building on community partnerships and using participatory-action research as a model. Beginning with a series of town halls to address the medical, social-emotional, support, and disability specific needs among our families, we transformed our practice by co-constructing panels with the community and within our UCEDD. We further amplified the voices and centered lived experiences of parents, PWD, teachers of children with disabilities and complex health care needs, as well as community organizational leaders in a conference and throughout our programs. Community partners contributed rich perspectives and expertise on the pre-pandemic conditions, the impact of the coronavirus on the self and community, as well as ways in which they pivoted, created synergies, and co-constructed initiatives. Outcomes from these events underscore the need for (1) community-engaging vs. community-facing discussions, (2) the creation of sustainable action plans that center the community and disability lived experience across a range of sociocultural and linguistic identities, and (3) moving beyond mere representation in EDI efforts toward authentic and equitable partnerships.

Introduction

Equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) have been at the forefront of many organizational initiatives, with awareness of the intersectionality of identities helping to broaden the scope of work with respect to race, ethnicity, and disability. While 26% of persons in the U.S. have identified having a disability, a long history of discrimination and abuse toward people with disabilities has been well documented in the disability literature (Carey, 2009; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2022b). People of color have also been subjected to a myriad of historical injustices, which include enslavement, medical experimentation, abuse, and sanctioned violence (Roberts, 2014; Skloot, 2017). Clinical and research institutions have been sources of programs and interventions yet have been both generative and complicit in the historical maltreatment and deficit-based views of racialized and minoritized populations, persons with disabilities, and particularly people of color with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD; American Psychological Association [APA], 2021). To address such injustices in the wake of civil unrest and heightened awareness, institutions, including University Centers for Excellence on Developmental Disabilities (UCEDDs), have taken efforts toward promoting equity in their practices, such as intentional community engagement and amplifying lived experiences.

Our center is a UCEDD, as well as one of 60 Leadership in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities (LEND) training centers, funded though the Maternal Child and Health Bureau. Recently reauthorized under the Developmental Disabilities and Bill of Rights Act of 2000 (PL 106-402), UCEDDs have since become sites for interdisciplinary and collaborative learning among university trainees, clinicians, researchers, educators, family members, self-advocates, and direct support professional, as well as service delivery for people with disabilities across the lifespan. Further descriptions of these entities can be found at www.aucd.org. In response to current social and political injustices, our UCEDD has considered the cultural, linguistic, experiential, and socioeconomic factors impacting EDI as they relate to our programs and practices.

The communities surrounding our center, comprised of Black American, Caribbean, and Latino residents, bring rich cultural, ethnic, linguistic, and historical identities. They have also been subjected to a long history of economic disenfranchisement and massive gentrification efforts, realities that have contributed toward a historical and present distrust of institutions (Allain & Collins, 2021; Khazanchi et al., 2020; Newman, 2022). Additionally, disparities and systemic inequities in education and health outcomes for Black, Latino, and Native communities were magnified during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they experienced adversities at heightened degrees (Hatcher et al., 2020).

A Pandemic Overlaying an Inequity Endemic

In March 2020, COVID-19 significantly impacted the healthcare and support service systems, the families and children served, as well as the overall community. Data revealed disproportionately high transmission rates among Black, Latino, Native, and Asian communities (Chakraborty, 2021). Disparate risks for severe illness and death for persons with disabilities, particularly for people with IDD, and compound risks for individuals at the intersections of race and disability were identified (CDC, 2022a). In addition, while the CDC noted that people with disabilities are generally not at greater risk for contracting COVID-19, existing systemic and structural inequities, such as disparate access to care, inequities in housing, living in congregate settings, and reliance on direct support professionals for care, may magnify adverse outcomes, especially for persons with IDD (CDC, 2022b).

How do we interpret those findings when these populations have had pervasively disparate access to healthcare, resources, and other agents of stability, while also having historical distrust of institutions because of maltreatment (National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [NIMHD], 2022)? An underlying endemic of inequity predated the pandemic, as social and systemic conditions contributed to disparate outcomes before the outbreak of COVID-19 (Khazanchi et al., 2020; Maestripieri, 2021). Braveman and Gruskin (2003) have warned the interpretations of health inequities not to be conflated with health inequalities, assigning causality to social determinants among populations based on their identity, ethnicity, or presentation. As such, researchers have called for greater attention to the structural and system-level inequities of COVID-19 that lie upstream of the disparate health manifestations at the population level (Khazanchi et al., 2020; Sabatello et al., 2021).

Toward Developing an Operative Framework

An “operationalization” of working toward health equity was described by Braveman and Gruskin (2003), who emphasized that the development of key protocols to remove the systemic barriers that impede the global health, safety, and well-being of the most historically disenfranchised groups should be an active process. Table 1 incorporates insights from the literature to inform our research evaluation framework and analyze the UCEDD’s initiatives. This operative framework centers equity and considers intersectionality in the context of critical disability theory, health equity, and lived experience (López & Gadsden, 2016; Oliver, 1998; Toombs, 1995).

| Key Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Self-Assessment | National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC, n.d.a) at Georgetown University provides tools for self-assessment and emphasizes self-reflection as “an ongoing process, not a one-time occurrence,” which serves to assess individual and collective progress over time and build the capacity of organizations and communities served. |

| Reflective Practice | Ghaye and Lillyman’s (2010) 12 Principles of Reflection used in healthcare emphasized the link between reflection on one’s practice and learning from lived experience as a means of systematically improving delivery of care. We highlight tenet number four, which states, “Reflective practice is about learning how to account positively for ourselves and our work” (p. 12). |

| Intersectionality | Considers how oppressions are magnified for individuals holding multiple historically marginalized identities (Crenshaw, 1989), while also considering “domains of power” (López & Gadsden, 2016). |

| Equity | Framing equity as a highly ethical principle for being fair and just; removing systemic barriers and policies that disproportionately impact populations (Braveman & Gruskin, 2003) |

| Community-Based Participatory Approach (CBPA) | Set the stage for authentic community-academic partnerships, situating community-based organizations as equal partners and empowering communities to address their self-identified concerns and needs (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020). |

| Emancipatory Research | Empowering communities to address their self-identified concerns and needs; also considers how the dynamics of power “works to limit opportunities, create marginalization, and perpetuate inequities” (Wesp et al., 2018). |

| Capacity Building | Existing EDI Action Plans suited for the context of the UCEDD network to build community and organizational capacity (Crimmins et al., 2019; NCCC, n.d.b) |

It was evident that a critical analysis of post-pandemic practices was needed. We researched several approaches and methodologies from healthcare and other industries to find an appropriate tool for assessing continuous process improvements and analyzing our initiatives. However, we found that several of these approaches lacked the deeply reflective process found in our review of cultural, disability, structural, and contextual perspectives, a fundamental step toward building equity and a hallmark of emancipatory research (Crimmins et al., 2019; Doan et al., 2021; Ghaye & Lillyman, 2010; NCCC, n.d.a; Reed & Card, 2016; Wesp et al., 2018).

We also found it necessary to make an explicit point of placing equity at the forefront of diversity, and inclusion. Although these are inseparable elements, diversity and inclusion are not substantiated without the emphasis on ethics and justice that are the foundations of equity. In addition, without equity taking the lead in commonplace EDI initiatives, organizational actors fail to implement action steps that remove systemic barriers. Therefore, in this paper we are purposeful in our ordering of equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) and its acronym.

Scholars have emphasized how reflection must occur at both the organizational and individual level in order to promote equity (T. J. Johnson, 2022; NCCC, n.d.b; Wesp et al., 2018). Alternatively, the 5Rs Method was developed as a critical analysis, applicable for persons with IDD, their families, and communities, who have been historically excluded from the research process (K. R. Johnson et. al, 2021; Taylor, 2018).

We sought to investigate how our center promoted and operationalized equity in clinical, training, research, and community-engagement practices. The following research questions were used as guidepost.

- How did our internal and external efforts reflect EDI and/or advance its practice?

- How did our community-academic partnerships (CAP) support interprofessional and inclusive community engagement?

- How did we amplify the voices of families, children, and self-advocates with lived experiences, particularly at the intersectionality of racial and ethnic diversity and disability?

The following analysis is a responsive evaluation of our UCEDD’s initiatives, applying reflective practices and a scoping review of existing EDI frameworks and related literature.

Key Terminology

- Community-academic partnerships:

- Partnerships formed by academic institutions with communities and/or organizations in efforts to work together towards a common goal/initiative (Drahota et al., 2016)

- Community-based participatory approach:

- Approach that includes community members as shared decision-makers and promotes mutual benefit (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006)

- Critical disability theory:

- Views ability as a cultural, historical, relative, social, and political phenomenon, using multiple theories and approaches; considers how power operates across systems over time (Meekosha & Shuttleworth, 2009).

- Emancipatory research:

- Approach to research that considers and shifts the power, social, and practical dynamics to research partners and participants (Oliver, 1997).

- Equality:

- The concept of sameness or equivalence in number or outcomes that can be measured.

- Equity:

- An ethical concept that incorporates social justice and fairness; does not necessarily mean sameness (Braveman & Gruskin, 2003).

- Intersectionality:

- Consideration of an individual’s identities, including race and gender, and how one experiences the world, discrimination, and oppression (Crenshaw, 1989).

- Lived experience:

- Representation and valuing a person’s experiences and lived knowledge as expertise (Given, 2008).

- Reflective practice:

- Ongoing, dynamic process of thinking critically to develop new understanding and advance practice (Schön, 1983).

- Responsive evaluation:

- Considers issues and concerns of involved parties, favoring personal experiences, meaning, context, and culture in assessing quality and worth of programs and practices (Stake, 1983).

- Social determinants of health:

- The set of conditions in which people are born, grow, live, etc., including their interactions with family, community members, systems, and institutions, which have an impact on their health, well-being, and access to care (NCCC, n.d.c).

Methods

Using responsive evaluation (RE), a qualitative approach, we employ the 5Rs method to analyze some of the past 6 years of our UCEDD’s initiatives with regards to EDI, including those prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. RE was selected because of its explicit focus on context and personal experience. As explained by Stake (1975), RE “orients more directly to program activities than to program intents, responds to audience requirements for information, and if the different value perspectives of the people at hand are referred to in reporting the success and failure of the program” (p. 65). Among the key features of RE, we highlighted “identification of issues and concerns based on direct, face-to-face contact with people in and around the program” (Patton, 2015, p. 207). We considered our UCEDD’s initiatives that have occurred chronologically, beginning with our most recent strategic plan, current organizational structure, programs, services, community partnerships, and COVID-19 responses that related to EDI practices.

Using the 5Rs method as an assessment tool and our research questions as a guidepost, we engaged in retrospective review and reflection of our initiatives through iterative discussion and collaborative teaming. We selectively analyzed these through the lens of the 5Rs: reflect, review, represent, revise, and respond. We posed the following questions in consideration of how each initiative related to the 5Rs.

- How does this initiative demonstrate one or more of the 5Rs?

- What operative framework(s) does this initiative align with?

- How does this initiative amplify lived experiences and community voices?

- How does this initiative inform revision of our practices and programs?

- How does this initiative respond to the needs and strengths of families and communities?

We emphasize that application of the 5Rs is not linear but rather fluid and iterative, as depicted in Table 2.

| 5Rs method | Description of the 5Rs | Center initiatives | Operative framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflect | Reflecting at the individual, disciplinary and institutional level |

|

|

| Review | Reviewing our goals and the processes by which we seek to

achieve them |

|

|

| Represent | Representation among impacted individuals and community partners to inform needed process change |

|

|

| Revise | Revising our goal-oriented actions, including service delivery and community initiatives |

|

|

| Respond | Responding by developing new and innovative strategies to better reflect equity aims |

|

|

Results

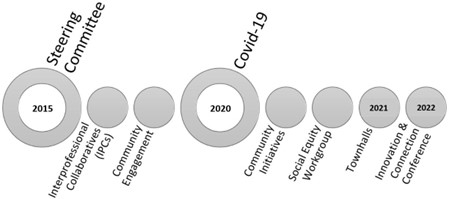

We used the 5Rs method to assess EDI within our partnerships, the intersectionality of our practices, and the centering of disability, family, and community lived experiences. The timeline in Figure 1 outlines selected initiatives that were considered with respect to EDI: (1) internal and external to the UCEDD, and (2) at the individual and collective level. The results of these analyses are discussed in the next section, in alignment with research questions, center initiatives, and 5Rs.

Setting the Stage: The Interprofessional Collaboratives (Review, Revise, and Represent)

In 2015, our UCEDD restructured the leadership model into a monthly steering committee meeting, replaced the previous discipline-directors model, and later added leaders from local community organizations. Simultaneously, the practices at our center were reorganized into five Interprofessional Collaboratives (IPCs): Neurodevelopment—Discovery Science, Neurodevelopment—Intervention Science, Promoting Behavioral Health, Community Wellness, and Lifespan. The work of the core participants in the IPCs propelled the original revision of organizational structure and strategic planning, garnered from discussions and feedback among our LEND faculty, staff, and family and community advisory committee. Some IPCs prioritized representation and inclusion of family members, self-advocates, and community leaders in addition to the LEND and discipline-specific core faculty and staff members.

Arguably, the IPCs’ work exercised the review, revise, and represent components of the 5Rs method. Our center reviewed current practices, intentionally revised organizational structures, and sought increased representation across programs, with an emphasis on lived experiences and community voices. Overall, the purpose of this restructure was threefold—first, to remove the walls of discipline-specific silos and promote interdisciplinary collaborations in clinical, training, and research work. Second, we aimed to engage and more effectively serve communities, specifically diverse minoritized families and children living with disability. Last, the IPCs collaborated with the Steering Committee to revise the center’s strategic planning and realign the programs’ goals with the center’s mission.

Rebuilding Trust: Community-Academic Partnerships (CAP) (Revise and Respond)

One outcome of our center’s ongoing revisions was the review of extant partnerships with three local communities. Collaborating with leaders from these community-based organizations aligns directly with the core values of the center and becomes core to the represent and revise processes. Thus, revising the rapport and partnerships with these communities became a primary step toward more collaboration and improved responsiveness. CAP resulted in the extension of professional development programs and community-based satellite sites for developmental, health, and behavioral health interventions for children and families. Ongoing invested efforts into CAP becomes a process-based outcome of representation and responsiveness, instead of an end-goal or product.

Recognizing the history of distrust within a historically Black community, for example, Beverly, a leader of one of our partnering community organizations, shared just how vital it was to rebuild this through intentionality, collaboration, and actionable steps. As a Black woman invested in sustaining the community’s holistic well-being, Beverly emphasized, trust is something that is earned, at the individual, societal, community level. And I think it’s two-fold…the system…from politics, to resources, to leadership, all of those factors I think play a role in how individuals respond (Ashley, 2022).

“Shining a Light on the Cracks,” Realities of COVID-19 (Review and Respond)

Against the backdrop of historical distrust from communities, the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Black and Latino communities was a reality the center’s employees, practitioners, clients, and partners witnessed. Angela, a local early childhood community agency leader, expressed, “It wasn’t difficult to figure out that disproportionality was going to weigh heavily during the pandemic. We were calling that out during the first few weeks, first few months. And then the data started coming in.” Indeed, communities serving individuals and families holding multiply marginalized identities were impacted heavily by COVID-19. Nancy, a community organization leader serving Latino families, described the pandemic as magnifying issues that were already present within the community systems of health care, “All COVID did was show us where the cracks were and just shine the light right through them.”

These realities prompted review and responses, spurring improved protocols and changes to healthcare delivery and psychosocial supports for those seeking services. One response galvanized a partnership between one of our community partners and our center’s mobile clinic to promote community vaccine access, with later addition of mental health supports.

Laying the EDI Groundwork: Social Equity Initiatives (Reflect, Review, Represent, and Respond)

The COVID-19 pandemic’s onset and parallel heightened social injustices became the impetus for additional revisions and increased reflective awareness of inequities and systemic racism. The deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery fueled questioning and awareness of whether our strategic planning and organizational structure reflected equitable, diverse, and inclusive aims. In the same month, Daniel Prude, a Black man with IDD and mental illness, lost his life because of police brutality, magnifying injustice at the intersection of race and disability. After a delayed response to these issues, the university issued a statement, convened listening sessions, and established multiple task forces.

In June 2020, our center formed an interdisciplinary Social Equity Workgroup (SEW) to reflect and review existing inequities within our programs and practices. SEW’s charge was to (1) understand the issues and current/developing practices of [our center] to address systemic racism and social injustices, as well as build equity, relationships, and respect for the individual; and (2) develop a process to address these issues on an individual, professional, and community level. The SEW met weekly and occasionally engaged the steering committee to seek organizational support and identify EDI challenges for faculty, staff, and trainee participants. They conducted a center-wide self-reflection questionnaire to collect perspectives on existing inequities. Survey participation and debriefing of findings exemplified emerging steps toward individual and collaborative reflection and representation. In response to the results of this assessment, the workgroup proposed recommendations to promote EDI, including: (1) hiring an external reviewer of our practices; (2) designating an internal social equity champion, and (3) increasing cultural, linguistic, and disability representation across programs, positions, and within the SEW. The SEW’s recommendations laid the groundwork for revision and further responsiveness of our programs and practices.

Amplifying Voices: Learning from Self-Advocates and Families (Reflect and Review)

Using a participatory action model to guide our reflection and review, members of the LEND faculty and staff engaged our disability self-advocates, family members, community organizations, and community advisory council members to center the community and disability lived experience during COVID-19. They expressed several concerns about pandemic-related care and protections, such as COVID-19 vaccine development, dissemination, and access. Self-advocates raised concerns about the already disparate access to healthcare, increased COVID-19 transmission rates in the disability community, lack of transportation access to vaccination sites, and unprepared sites to serve the needs of people with disabilities, further compounding access. Community leaders collectively expressed how residents of color with disabilities were experiencing magnified economic challenges during the pandemic (e.g., needs related to rental, food, and utility assistance). Mirlene described the extreme health and economic toll the pandemic had taken on the Haitian community. These leaders emphasized their own struggles “straddling the community and professional” worlds, while also being “collectors of data.” Acknowledging the impact of the community’s historical distrust of institutions, Nancy noted the pandemic was “the perfect storm” that amplified “many systemic issues down the line,” ranging from access challenges related to technology to vacillating resources.

Community members had a slew of unanswered questions that did not fit pandemic-related mainstream information, engagement protocols, or universal supports. A parent of an adult with IDD who is a member of the community advisory council and interprofessional collaborative expressed frustration and distress over awaiting his son’s approval for the COVID-19 vaccine. Knowing the greater risks his son faced and after approval, staff struggled to provide disability support by saying, “We cannot handle your son.” Additionally, families and community members expressed concerns about who to trust when faced with conflicting information shared across news, social media platforms, and local communications. Simultaneously, many organizations, hospitals, school districts, and other entities began hosting webinars and townhalls around COVID-19 in hopes of reaching and educating people en-masse about COVID- 19 and the safety of vaccines.

Our center’s response began with a townhall featuring self-advocates and a physician. We engaged individuals from our self-advocate leadership program alumni network to select a trusted physician for the call. In March of 2021, the first townhall launched virtually, Real Talk: Ask the Expert about your COVID-19 questions. This was co-facilitated by a case manager from an autism center and two self-advocate leaders at our center, being the first of its kind to be led and fully attended by self-advocates. The debriefing sessions with self-advocate alumni informed two subsequent “Real Talk” townhalls and focused on specific self-identified priority topics: safety protocols and navigating public spaces when there are differing decisions about vaccinations.

As the summer months drew on and the return to school and work was imminent, the authors of this paper assembled as a team representing three distinct disciplines—occupational therapy/early childhood education, special education/family advocacy, and social work/early childhood mental health. We discussed the need to support families’ questions, particularly those of children with disabilities and complex healthcare needs, whose concerns the previous panels did not address comprehensively. We envisioned a family-centered townhall, a notable shift from the traditional practitioner-driven formats. Additionally, we asked what could collectively contribute to the panel and what additional disciplines could provide a more holistic response to families. Our final panel included a social worker, occupational therapist, family navigator/parent of a child with a disability, pediatrician, and pediatric psychologist. We developed the agenda based on families’ questions and concerns solicited from the registration page, leveraging professional expertise to provide guidance on topics. Furthermore, polls were used throughout the townhall to gather families’ perspectives. The family townhalls were a three-part “back-to-school” series, with the first two in English and the last in Spanish.

Nearly 70 attendees participated across the three townhalls, which families described as “very informative” and “helpful.” The open-ended feedback from participants suggested we reached families who might not have had access in previous group settings, as one parent shared, “I wish all foster parents and PTAs would get notices for trainings/discussions on kids and COVID.” A participant expressed the impact of the program as she prepared for the school year, “My questions were answered. It eased my anxiety as a mother sending my children back to school in the middle of a pandemic.”

New Ways of Knowing: The Community-Disability Lived Experience (Reflect, Represent, and Revise)

The authors of this paper planned sessions for the 2022 Innovation and Connection Conference, with an average of 200 attendees. Early childhood development and COVID-19 was the central theme. Drawing from the insights gleaned from the aforementioned virtual townhalls, the intent was to generate a panel that was not merely inclusive of the local communities but engaging them in ways that were responsive to their concerns. How could this panel be designed to further amplify the voices and lived experiences of our community members? How could this panel promote value and ways of knowing beyond academia and the clinical-professional expertise that dominated our network and its activities?

Aligning with the reflect, represent, and revise domains of the 5Rs model, the initial step was a shift from the panel organizers’ clinical and academic research roles to ones of liaisons, developing an organic conference with communities to inform professionals about first-hand experiences of COVID-19 from a community-disability and intersectional lens. In doing so, conference organizers were repositioned as moderators and uplifters of voices, rather than panelists. Second, in alignment with a community-participatory model, panelists with differing standpoints were sought out to provide diverse perspectives and lived experiences. Angela, an organizational leader, emphasized that “there is not a deep sense of equity and equality in our communities across people [and] institutions.” Incorporating both representation and revision, our conference panelists mirrored our centers’ core priority of interdisciplinary teaming and resulted in a diverse panel of self-advocates, family members, community agencies, and organizational leaders. Their perspectives provided critical insights into personal and professional experiences during the height of COVID-19 (Table 3).

| Panelist | Role | Panelist quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Angela | Black Woman, Organizational Leader | “We worked very reflectively and intentionally to redesign our service delivery model.”

“We had our staff training, from 9 in the morning to 9 at night, mostly women, with telephones, surrounded by their children, facing their own inequities. But [they stayed] because of their ongoing commitment to children.” “[Need to include] early childcare workers as essential workers.” “It is important that all of us roll up our sleeves to continue to support communities, families, and children.” “We want to continue to find innovative ways to engage.” “We need to recognize the digital divide and that it is very prevalent… and many are left behind. “How can we make digital access truly accessible?” |

| Claudine | Black Haitian Woman, High School Senior, Self-Advocate | “The pandemic happened in my sophomore year of high school…it changed a lot.”

“I had to stay in the house because I was high risk…and it was an adjustment…we just got used to it.” “I was in virtual school… and it was pretty simple for me because I had already done it…my freshman year.” “All of [my doctor’s appointments] were through Zoom…and when my doctor asked me to do lab work, I was able to use a platform and get my blood drawn [at] my house…because in my opinion labs are not safe.” “I was concerned…I had never met anyone with my particular type of dwarfism.” “Being a person with a disability… I think it’s really important to be a voice in the community.” |

| David | White Man, Mental Health Professional serving Black and Latino families | “Had to completely revamp, rechange our model and how we help our participants and grieving individuals”

“Had to work with whatever they have in their house…and scheduling became a lot more of an issue” “A lot of creative solutions in a short period of time and we all worked together and found a way to make it work.” “It has been quite beneficial to people and the organization…we have been able to expand our reach to communities and areas across the country to people who have not had access to grief support…individuals with disabilities can now log into our groups” “Holistically, it has really brought the conversation about grief to the forefront…all of our stories are different but there can be shared commonalties, shared elements that can bring us together and we can find connection and support through that.” |

| Mirlene | Black Haitian Woman, Organizational Leader | “People who didn’t speak English, had literacy issues and technology challenges were unable to do [unemployment application] on their own…so we made the decision that there was no pivoting for us, and we were going to remain open…and some other services were going to need to be held online.”

“You are dealing with a community where technology is a weakness…and people have smartphones and don’t know how to use [them].” “To remain mission aligned, we had to be there in the trenches with the people…and we were kept extremely busy.” “We surveyed our partners and gained a deep understanding of how people communicated and really tried to engage our community based on those means. We also created a tech literacy program…prioritizing parents who were facing extreme challenges.” “Our mental health counselors, working with children and families, did the virtual counseling, finding issues with privacy issues…and we haven’t mastered that technology barrier yet.” “Parents are very happy when they are able to access the technology and follow at their leisure…we know that the digital divide is still deep.” |

| Monique | Black Mother of Four Children, Community Resident, Community Builder | “When the pandemic first started, it was very crazy for me and my family…and I worked at a grocery store back then…and we had to stay in the house for 2-3 weeks at a time.”

“My youngest is a 3-year-old and her daycare didn’t close throughout the pandemic. I take my hat off to them…they were just very precautious.” “I have a respect for teachers and being a parent, we don’t know how it is for kids to be in the school system…I had to transition everything… with 4 different grade levels…I had to teach my kids and I had to learn how my kids learn and that was very hard at first.” “I got to know them on an educational level…the outcome was great…and very rewarding.” “I have my board up here; it’s not a schedule. Now I just have words of encouragement for them.” “Think about others before you think about yourself. You have to put yourself in other people’s shoes…and treat people how you want to be treated.” |

| Nancy | White Hispanic Woman, Organizational Leader | “We were there when everyone else shut down.”

“Staff were doing their day-to-day work and had to take on additional responsibilities.” “We advocated and worked closely with our elected officials.” “We had to take care of self-care for our staff.” “[We had] staff members who had children with disabilities themselves…struggling as well.” “Because we deal with a lot of immigrant and mixed status families, there was a lot of fear around that.” “For families that had little ones, especially with special developmental needs, it was extremely challenging for them…and it became even more important that we were there and added additional support so that they made it through.” “We were fortunate to have funders and donors locally and nationally.” “It was almost like a light through the cracks of what we had already know in many of our communities…tends to be a little behind in terms of technology, innovation, and delivering services.” “We still need that human connection…battling isolation and fatigue of technology. What can be more cost effective and delivered in a virtual setting?” |

| Rosemarie | Indian Woman, Special Education Teacher | “Medical professionals and first responders were bringing their children to the school. And our early childhood teachers were there every day.”

“We uprooted our little ones from a structured stable school setting to a new learning home environment and this is a big change for them… and tough adjustment.” “Students in the auditory oral program are hearing impaired…and the teachers were able to manage the quality of sound at school, but this was near impossible to do when the students were in the home environment and these factors caused the engagement to be very challenging for virtual learning, for both parents and the teachers.” “With a lot of planning and time, we were able to make schedules…that worked for the families and the kids.” “The dynamics of the house were different…and if virtual was not an option for parents, we always ensured there was some way…to keep in contact with our parents every single week.” “[With] parent coaching, we facilitated the parents’ understanding [of the] skills their child needed to know…parents were the teachers.” “Silver lining…it became easier and more convenient for our parents and extended family to join meetings and virtual family events we had in school.” |

A self-advocate, family member, community agency leaders, and organizational leaders each brought their unique and critical perspectives to the panel. Community, organizational leaders, and early childhood service providers discussed system-level fractures during the pandemic that negatively impacted their service delivery models. They also described how they pivoted through creativity, planning, collaboration, and flexibility. Notable challenges existed for institutions providing support services to families and children. For example, Rosemarie described challenges to provide virtual learning for parents and teachers for children with hearing impairments in their home setting. Nancy shared her own professional frustrations as she now competed with larger entities to hire qualified staff to meet increased consumer demands. Still, these leaders described ways in which they provided continuous care and support during a public health emergency.

One of the greatest insights from this session at the conference was the power and the aforementioned “synergies” among the community-disability voices. Across the organizations, schools, agencies, and communities, panelists described the increased access and participation for families, children, and people with disabilities. Panelists shared “silver linings” they discovered, embracing new virtual service delivery models and overcoming transportation and other structural barriers that increased access for families, children, and clients with disabilities. In addition, these new ways of knowing represent increased organizational responsiveness and community strengths.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess our center’s efforts in meeting the goals of diversity equity, and inclusion. Informed by emancipatory and equitable practices in research, we used the 5Rs Method to analyze the following efforts and initiatives across the past 6 years of our UCEDD: (1) internal and external initiatives advancing EDI practices; (2) CAPs supporting interprofessional and inclusive community engagements; and (3) approaches that might support and amplify the voices of families, children, and self-advocates with lived experiences, particularly at the intersectionality of racial and ethnic diversity and disability (Table 4). This approach is consistent with responsive evaluation, which examines the activities and actions, rather than the intent of a program or institution. Our findings revealed relevant inroads related to inclusion, yet we need to bolster our efforts toward developing diversity and equity.

| Research questions | 5 Rs | Center initiatives |

| How did our internal and external efforts reflect EDI and/ or advance its practice? | Reflect |

|

| Revise |

|

|

| How did our community-academic partnerships (CAP) support interprofessional and inclusive community engagement? | Represent |

|

| How did we amplify the voices of families, children, and self-advocates with lived experiences, particularly at the intersectionality of racial and ethnic diversity and disability? | Review

|

|

| Respond |

|

Commitment to Change: Internal and External Initiatives Advancing EDI Practices

One barrier to commitment and advancing EDI understanding and practice uncovered in both our review of the literature and our center initiatives was the gap between equitable intentions and actions. Ghaye and Lillyman (2010) emphasized how institutions of care must go beyond intentions, that even the best of intentions must be “properly and sensibly implemented, reviewed, and possibly refocused over time” (p. 11). Prior to the pandemic, the center’s reorganization into a two-entity structure, a Steering Committee and five IPCs, set the stage to reflect on ways the traditional organization of clinical or academic divisions blocked the fulfillment of expected aims for interdisciplinary collaborations. Collectively, the Steering Committee and IPCs’ reflective work in 2015, the onset of COVID-19, and the civil unrest of 2020 led to the review of the center’s strategic plan, bringing attention toward intentional engagement of those with lived experiences and the greater community. All of these activities demonstrated an intent toward EDI.

In this review, however, we did observe shortfalls in how our activities reflected EDI. One clear example was the dichotomy in the responses to the events of 2020. While the institutional response was focused on COVID-19 related health concerns, shift to remote work, and learning to maintain continuity of services; the response to racial inequity and violence against people of color was markedly delayed. Although the listening sessions did support some individual and group reflection, this was not done on a broad or timely organizational level, which is a necessary process to promote collective understanding (Crimmins et al., 2019). Task forces were established at the university level and our center formed the SEW to address specific internal issues related to EDI.

The SEW identified priorities, as well as developed and disseminated a center-wide survey, uncovering some of the barriers to true EDI within our practices. Although the center engaged and strengthened collaborations with a few neighboring community organizations, this may inadvertently limit the feedback and extension of our partnerships beyond these particular individuals and agencies. As a result, our center may not capture the full scope of community representation to increase engagement and expand the impact of our programs. Similarly, the SEW’s survey had limitations in capturing diverse perspectives beyond faculty and staff, with the voices of trainees, consumers, and the broader community missing, including lived experiences of individuals with IDD, whose voices and contributions are critical for developing appropriate programs and having a disability competent workforce (Bowen et al., 2020; de Castro, 2020). A diversity of perspectives, and considerations of intersectionality and power dynamics, are all necessary ingredients to reach an emancipatory goal and establish a culturally responsive workforce (Doan et al., 2021).

The work of the SEW illustrated the significance of the reflect and review practices to inform needed revisions (Ghaye & Lillyman 2010). In many ways, this workgroup demonstrated moving beyond a simple structural revision to include reflective and political components found within critical disability perspectives and EDI self-assessment tools (Crimmins et al., 2019; Goodley et al., 2019). Recommendations from the workgroup for both a champion of social equity and independent reviewer of EDI are consistent with the literature (Stanford, 2020). Considering the role of the champion, however, we draw from the poignant reflections by T. J. Johnson (2022), who noted the need for self-development over tasking such responsibility to a colleague harmed by actions of others, stating, “do the internal work of identifying the ways in which you personally uphold structures of racism and white supremacy; and make a commitment to being antiracist” (p. 3). Furthermore, the SEW’s recommended action steps reflect and support the need for intentional, purposive, and sustainable engagement of others external to our institution to inform EDI efforts at the individual, professional, and community level, since outcomes from self-assessments have the potential to make changes that reflect an emancipatory goal (Crimmins et al., 2019; Wesp et al., 2020).

CAPs: Supporting Interprofessional and Inclusive Community Engagements

Analyzing our CAPs in accordance with the literature and 5Rs method helped to further highlight the gap between intentionality to effect EDI and its practice, while also uncovering new perspectives on EDI through the lens of the community representatives (Ghaye & Lillyman, 2010). We looked at the initiatives’ diversity of perspectives, equity, inclusivity, and engagement of members internal and external to our center’s structures and practices. The introduction of the IPCs reflected an intentionality toward representation within the interprofessional initiatives, interdisciplinary practices, and collective expertise.

However, while some disciplines were overrepresented, there was a clear underrepresentation among other potential contributors to these collaboratives, such as the family discipline, lived experience, and culturally and linguistically diverse representatives from the disability community. Additionally, while community leaders participated in some of the IPCs and attended the Steering Committee meetings, the type of engagement was limited, as it did not incorporate the equitable, shared decision-making foundational to CBPA (Heymani et al., 2020). Although these initiatives involved some structural revisions, which reflect an intent toward increased representation and inclusion, equity should guide these efforts and move the needle toward removing systemic and structural barriers that impact their communities disproportionately, for which meaningful engagement is part and parcel (Crimmins et al., 2019; Oliver, 1998; Wesp et al., 2018). As our external efforts were both impacted and generated by COVID-19, these initiatives called for further review, revision, and resultant expansion of our community partnerships.

Maestripieri (2021) stated, “COVID-19 [was] not a great equalizer” but rather a magnifier of disparate impacts and outcomes, especially for minoritized and migrant communities who experienced inequitable access to care. The pandemic served as a means for operationalizing equity, which included responsiveness toward removing some of the systemic barriers (Braveman & Gruskin, 2003). How could we also rebuild trust with communities, whose relationships with institutions have been fractured? The external efforts of our center were inclusive, such as developing COVID-19 initiatives in partnership with the community, such as deploying the center’s mobile clinic and convening townhalls. The mobile clinic streamlined healthcare access in partnership with the community, including vaccinations and other services for under-insured and undocumented community members.

Equity was reflected in the design and shift of the self-advocate and family townhalls, as well as the conference panel, from the traditional, community-facing format toward a more organic and engaging one. We incorporated new ways of knowing, by centering the community-disability lived experience. The member checks and debriefing sessions preceding and following the COVID-19 townhalls also demonstrated equity and meaningful inclusion, as community perspectives were used to inform the design, engagement, and reflective practices. To that end, the conference initiative was perhaps the closest toward reaching an emancipatory goal, as the center’s organizers engaged community members as co-collaborators, empowering the community to share their self-identified needs, concerns, and strengths (Wesp et al., 2018).

Finally, although COVID-19 was the driving force for reflection, review, revision, and responsiveness toward new levels of community-based participatory approaches (CBPA), COVID-19’s best responses have come from collaborating with communities, who are sources of strength (Pastor et al., 2022). Actions to advance EDI could be to expand these multiple CAPs toward ongoing learning communities of practice and future emancipatory approaches. Heymani et al., (2020) discussed the combined CBPA in communities of practice in disability EDI work, noting, “Within communities of practice, participatory opportunities exist for collaborative approaches to advancing the disability-awareness agenda and the knowledge base relating to disability” (p. 4). By incorporating this into our center infrastructure, we have an opportunity to build the capacity of our own organization as well as the communities (Crimmins et al., 2019; Pastor et al., 2022).

Lived Experiences: Amplifying Voices at the Intersectionality of Racial and Ethnic Diversity and Disability.

Extending our new ways of knowing, a final step toward operationalizing equity was through amplifying voices, especially from communities that have experienced historical and pervasive disenfranchisement. This involves intentionally sharing power and platforms with individuals who have lived experience and their families at the intersection of racial and ethnic diversity in addition to disability. Results of the SEW’s survey suggested shortfalls in optimal diversity and representation internal to the center among members of the SEW workgroup, faculty, staff, and leadership that are needed to effectively drive equitable and meaningfully inclusive initiatives (Ghaye & Lillyman 2010). Debriefing sessions did occur internal to the organization to discuss the results of the survey distributed by the SEW, which was important for internal review and reflection. However, future considerations of equity could include a review that is: (1) continuous; (2) conducted collaboratively with community members, especially considering their histories of marginalization; (3) supportive and safe to consider dynamics of power which might constrain the voices of contributors; and (4) incorporated into the organizational infrastructure or systems change (Crimmins et al., 2019; Reed & Card, 2016). As Pastor et al. (2022) emphasized,

Community power-building organizations have a set of practices and capacities… academics can build a relationship with those groups and bring to bear some of the skills academics have as partners and not just observers or experts…not just as teachers but as learners. (p. 7)

Moving beyond representation, building an ongoing learning community alongside people with historically marginalized identities, lived experience of disability, and intersectionality could make substantial contributions and develop a reflective organization through empowerment.

The potential for establishing learning communities as a means for amplifying voices also carries over into the external initiatives. Several strengths with regards to EDI were identified among the reviewed initiatives. Emphatically, the self-advocate townhall series offered a particular reframing of “ask the expert”; while one might assume that the physician was the only expert on the call, in fact self-advocates established their expertise in sharing their experiences, concerns, and strategies for navigating the pandemic. Alternately, our external efforts could have uplifted the voices of people with lived experience, intersectionality, and the inclusivity of persons with IDD or disabled parents of color better. Diversity among self-advocates with disabilities, variety of lived experiences, and inclusion of families of individuals with IDD would help to advance the equity agenda. Given the harm caused by health research to people with IDD historically, to be included as collaborators in the research process, contributing to knowledge, and valuable to understanding ways of knowing is a step toward the emancipatory goals (Horner-Johnson & Drum, 2006; Taylor, 2018).

Acknowledging the ways in which community members have been historically and presently disenfranchised also calls for revisions to consider accessibility in our programs and platforms. As mentioned earlier, while learning communities between the center and partners could provide an equitable means for engagement, they should also center community needs and preferences. Notably, these involve a shift of power, for institutional faculty and staff to serve as liaisons and suspend their interpretations, to prioritize the concerns of the community (Wesp et al., 2018). Centralizing the voices of community members at multiple levels helped to explore the systemic and everyday challenges of intersectionality. From students with disabilities and their families to employees to organizational entities, COVID had created multiple fractures, many of which we run the risk of overlooking without the lived experiences and testimonials. This also raises questions about the underlying assumptions in meetings, townhalls, and conferences, which may not consider variations in technology access or the comfort and suitability of virtual spaces for some individuals. Certainly, these were barriers that families and community members identified about the shift to virtual engagement, telehealth, work, and learning for individuals with disabilities. In addition, advancing equity would include linguistic access, especially for speakers of Haitian Creole, Spanish, and other languages, considering the demographics of the local community. Altogether, future learning communities should reflect equitable and emancipatory approaches in townhalls, conference panels, service delivery, interdisciplinary collaborations, workgroups, community outreach, and other center initiatives, as this affords the opportunity to amplify the most important voices of all.

Strengths and Limitations

Through analysis and writing of this manuscript, we engage in reflexivity as a process, considering how we are ourselves immersed and situated within the very context we are assessing, while also considering ourselves to be agents of equity and emancipatory change. Reflexivity reminds us to be “attentive to and conscious of the cultural, political, social, linguistic, and economic origins of one’s own perspective and voice…the perspective and voices of [individual] interviews, and those to whom one reports” (Patton, 2015, p. 71). Reflexivity is a cornerstone of qualitative and ethnographic practices; it galvanizes the reflective process, examining our own intersectionality and positionality as Black and Brown Caribbean and Latina women researchers and clinicians within a predominantly White institution, with one of us being a mother of a child with IDD (Boylorn & Orbe, 2016; Patton et al., 2015). While our unique lenses lend themselves to addressing and examining inequity and biases, we also “acknowledge the inevitable privileges we experience alongside marginalization and to take responsibility for our subjective lenses through reflexivity” (Boylorn & Orbe, 2016, p. 15). Acknowledging how this could be perceived as a conflict of interest, we strived for reflexivity, using first-person language and an active voice to stay aware and introspective throughout the assessment and writing. Finally, we do not propose to be value-neutral but rather value-laden, prioritizing the disability lived experience, sociohistorical, racial equity, community, and intersectionality perspectives.

To that end, a strength of this study is both the self-examination and analysis of our institutional culture, as well as the ways we are serving the communities connected or affiliated with the institutions. One common shortfall we observed throughout this organizational self-evaluation was the need for more inclusive and diverse lived experiences, including individuals with IDD, whose voices, perspectives, concerns, and representation are limited in the center’s leadership, faculty, staff, trainees, and programs. Additionally, the internal and external initiatives did not consistently address intersectionality, engaging people of color with disabilities and their families, whose experiences of health and social inequities are so often magnified. Finally, advancing EDI requires moving beyond structural and programmatic representation, which implies merely being present and included performatively, toward emancipatory practices that intentionally and meaningfully center and incorporate the perspectives and authentic partnerships with individuals from the Black, Latino, and disability communities.

Implications

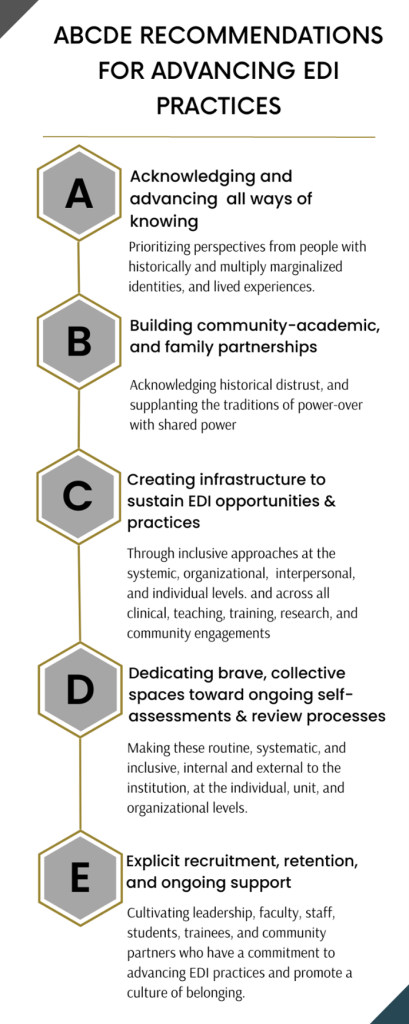

We note the preliminary nature of the 5Rs method and suggest its use for analysis of similarly situated institutions at the nexus of clinical healthcare, community programs, and disability services and supports. As noted by researchers, impactful EDI initiatives require an organizational supportive environment, iterative consultations with community members, and system-level changes (Reed & Card, 2016). Because contexts are fluid, complex, and dynamic, yet vital for informing revisions, future studies could pilot this method to assess its feasibility and efficacy across settings. As such, we present the implications from this study, ABCDEs, as recommendations for future analysis. These are specific recommendations for organizations with a focus on clinical training and research practices to move beyond representation and advance equity, helping guide critical analyses that lead to authentic actions and commitments to EDI at the individual and organizational levels (Figure 2).

Conclusion

This qualitative evaluation engaged reflective practices and used the 5Rs method to analyze the center’s response to critical moments, including COVID-19 and the intersectionality of racism and ableism, with subsequent transformation to address EDI and systemic injustices. The 5Rs method, developed as an operative framework, incorporates theoretical foundations and tools to examine our initiatives for EDI, notably Critical Disability Studies, intersectionality, lived experience, Community-Based Participatory and Emancipatory Research approaches, and the extant EDI frameworks developed for UCEDDs.

How did our internal and external efforts reflect EDI and/or advance its practices? Several internal changes prior to the pandemic reflected the intent for EDI and set the stage for future transformation. Although the intent to bolster our EDI practices existed prior to COVID-19, the events undoubtedly resulted in the magnification of preexisting disparate health access, care, and outcomes for the communities we served. Collectively, these experiences presented a unique and unprecedented opportunity to follow through on our commitment to institutional, interprofessional, intrapersonal, and community transformations. As noted, the internal efforts laid down the groundwork for further efforts in the community, reflecting EDI to a greater degree.

We acknowledge the contentions within our own center, where our desire and intention to do better were both met and challenged by the opportunity to improve our practices. A public health emergency such as COVID-19, intersecting with racial inequity and systemic injustices experienced by people of color, created a perfect storm to shift a slow and reactionary equity movement toward a more intentional one, generating the need for reflective practices and purposive action steps. The CAPs were vital to the needed representation, voice, and partnerships within our interprofessional collaboratives and community engagements. Most importantly, these were critical for rebuilding trust with the communities and informing the next steps.

At the foundational level of reflexivity, a critical self-assessment at both the individual and organizational level is needed, accounting for power, privileges, and social advantages with internal and external communities. One example of this was the internal assessment initiated by the SEW, which identified the need to transform our interactions with colleagues and trainees, our collaborations with communities, as well as our patient and family practices. A movement toward intentional practices and emancipatory work is more than just an intellectual exercise, involving agency, advocacy, the deep understanding of processes, and activism.

Braveman and Gruskin (2003) emphasized the need to shift the focus from disparate outcomes and social determinants toward the systemic causes of inequity, critical for promoting health equity among communities who have been historically and systemically marginalized. Given the ways in which research has been historically exclusionary and harmful toward people with IDD, people of color, and people with IDD experiencing intersectionality based on holding both of these identities, researchers must consider their practice as a place where more equitable and transformative work can begin (Oliver, 1998; Roberts, 2014). The pandemic presented an opportunity for amplifying the voices of key individuals, such as caregivers of young children with disabilities, CAP leaders, residents of our CAP communities who served as community builders, self-advocates, direct service providers, and people with lived experience, especially people experiencing intersectionality based on the holding historically marginalized racial, ethnic, and disability identities. The priorities for EDI uncovered in our review was consistent with research, which have emphasized the role of people with IDD, as well as disabled people of color as valuable contributors to ways of knowing (Johnson et al., 2021; Taylor, 2018). Undoubtedly, community members with diverse identities and perspectives are key collaborators with centers and institutions for designing and improving EDI initiatives.

As centers and institutions like ours take initial steps toward EDI, the advancement toward knowledge and practice may not be universal, and intentional steps toward self-assessment might be hampered by resources and capacity, evidenced in our review (Wesp et al., 2018). However, prioritizing community voices will continue to be a driving force for EDI, as Pastor et al. (2022) noted,

community members can hold community power organizations, academics, and policy makers accountable to the community and the change they want to see in the world…to push against institutional tendencies to pursue incremental change rather than transformational change. (p. 4)

Institutions need to consider how critical it is to amplify voices in order to promote change that is responsive and matters to the community, thus, providing mutual benefit.

As a final note, we do not propose the 5R method to be generalizable to all settings, but rather useful to other similarly situated centers and contexts. We bring our values to our practice, as scholars and clinicians, being activists in our own communities. Moving the needle toward emancipatory practices involves a degree of discomfort and giving up power to disrupt the systemic inequities while also recognizing the deficit ideologies that undergird them. However, we can leverage our collective strengths in collaboration with communities and those with lived experience to become promoters of equity, in both theory and practice.

References

Allain, M. L., & Collins, T. W. (2021). Differential access to park space based on country of origin within Miami’s Hispanic/Latino population: A novel analysis of park equity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 8364. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168364

Ashley, J. L. (Director) (2022). Outbreak: The impact of COVID-19 on the community. [Documentary]. Urgent, Inc.

American Psychological Association. (2021). Apology to people of color for APA’s role in promoting, perpetuating, and failing to challenge racism, racial discrimination, and human hierarchy in U.S. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/racism-apology

Bowen, C. N., Havercamp, S. M., Bowen, S. K., & Nye, G. (2020). A call to action: Preparing a disability-competent health care workforce. Disability and Health Journal, 13(4), 100941.

Boylorn, R. M., & Orbe, M. P. (2016). Introduction critical autoethnography as method of choice. In Critical Autoethnography (pp. 13-26). Routledge.

Braveman, P., & Gruskin, S. (2003). Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 57(4), 254-258.

Carey, A. C. (2009). On the margins of citizenship: Intellectual disability and civil rights in twentieth-century America. Temple University Press.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022a). Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022b). People with certain medical conditions. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

Crimmins, D., Wheeler, B., Wood, L., Graybill, E., & Goode, T. (2019). Equity, diversity & inclusion action plan for the UCEDD national network. Association of University Centers on Disabilities: Silver Spring, MD.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989, Article 8. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8/

Chakraborty, J. (2021). Social inequities in the distribution of COVID-19: An intra-categorical analysis of people with disabilities in the US. Disability and Health Journal, 14(1), 101007.

de Castro, M. G. C. (2020). Participatory methodologies with persons with intellectual disabilities: A theoretical literature review. New Trends in Qualitative Research, 4, 343–361. https://doi.org/10.36367/ntqr.4.2020.343-361

Doan, T., Kim, P. B., Mooney, S., & Vo, H. Y. T. (2021). The emancipatory approach in hospitality research on employees with disabilities: An auto-ethnographic research note. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62(1), 46-61.

Drahota, A., Meza, R. D., Brikho, B., Naaf, M., Estabillo, J. A., Gomez, E. D., Vejnoska, S. F., Dufek, S., Stahmer, A. C., & Aarons, G. A. (2016). Community-academic partnerships: A systematic review of the state of the literature and recommendations for future research. The Milbank Quarterly, 94(1), 163-214. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12184

Given, L. M. (2008). Lived experience. In The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 490-490). SAGE Publications. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909.n250

Goodley, D., Lawthom, R., Liddiard, K., & Runswick-Cole, K. (2019). Provocations for critical disability studies. Disability & Society, 34(6), 972-997. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1566889

Ghaye, T., & Lillyman, S. (2010). Reflection: Principles and practices for healthcare professionals. Andrews UK Ltd.

Hatcher, S. M., Agnew-Brune, C., Anderson, M., Zambrano, L. D., Rose, C. E., Jim, M. A., Baugher, A., Liu, G. S., Patel, S. V., Evans, M. E., Pindyck, T., Dubray, C. L. Rainey J. J., Chen, J., Sadowski, C., Winglee, K., Penman, A., Dixit, A., Claw, E., … McCollum, J. (2020). COVID-19 among American Indian and Alaska native persons: 23 states, January 31–July 3, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(34), 1166-1169.

Heymani, S., Pillay, D., De Andrade, V., Roos, R., & Sekome, K. (2020). A transformative approach to disability awareness, driven by persons with disability. South African Health Review, 2020(1), 1-9. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-healthr-v2020-n1-a4

Horner‐Johnson, W., & Drum, C. E. (2006). Prevalence of maltreatment of people with intellectual disabilities: A review of recently published research. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 12(1), 57-69

Johnson, K. R., Bogenschutz, M., & Peak, K. (2021). Propositions for race-based research in intellectual and developmental disabilities. Inclusion, 9(3), 156-169.

Johnson, T. J. (2022). “Your silence will not protect you”: Using words and action in the fight against racism. Pediatrics, 149(2), 1-4.

Khazanchi, R., Evans, C. T., & Marcelin, J. R. (2020). Racism, not race, drives inequity across the COVID-19 continuum. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2019933- e2019933.

López, N., & Gadsden, V. L. (2016). Health inequities, social determinants, and intersectionality. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Health-Inequities-Social-Determinants-and-Intersectionality.pdf

Maestripieri, L. (2021). The Covid-19 pandemics: Why intersectionality matters. Frontiers in Sociology, 6, 642662–642662. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.642662

Meekosha, H., & Shuttleworth, R. (2009). What’s so ‘critical’ about critical disability studies? Australian Journal of Human Rights, 15(1), 47-75.

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIHMD). (2022). COVID-19 information and resources. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health. https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/programs/covid-19/

National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC). (n.d.a). Self-assessments. Georgetown University Center for Developmental Disabilities, Georgetown University. https://nccc.georgetown.edu/assessments/

National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC). (n.d.b). Foundations: Conceptual Frameworks / Models, Guiding Values and Principles. Georgetown University Center for Developmental Disabilities, Georgetown University. https://nccc.georgetown.edu/foundations/framework.php

National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC). (n.d.c). Curricular Enhancement Module Series 4. Georgetown University Center for Developmental Disabilities, Georgetown University. https://nccc.georgetown.edu/curricula/resources_mod4.html.

Newman, P. A., Reid, L., Tepjan, S., Fantus, S., Allan, K., Nyoni, T., Guta, A., & Williams, C. C. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among marginalized populations in the US and Canada: Protocol for a scoping review. PloS One, 17(3), e0266120.

Newman, A. (2022). Moving beyond distrust: Centering institutional change by decentering the white analytical lens. Bioethics, 36(3), 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12992

Oliver, M. (1997). Emancipatory research: Realistic goal or impossible dream. Doing Disability Research, 2, 15–31.

Oliver, M. (1998). Theories in health care and research: theories of disability in health practice and research. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 317(7170), 1446–1449. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7170.1446.

Pastor, M., Speer, P., Gupta, J., Han, H., & Ito, J. (2022). Community power and health equity: Closing the gap between scholarship and practice. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202206c

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage publications.

Reed, J. E., & Card, A. J. (2016). The problem with Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(3), 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-005076

Roberts, D. (2014). Killing the Black body: Race, reproduction, and the meaning of liberty. Vintage.

Sabatello, M., Jackson Scroggins, M., Goto, G., Santiago, A., McCormick, A., Morris, K.J., Daulton, C.R., Easter, C. L. & Darien, G. (2021). Structural racism in the COVID-19 pandemic: Moving forward. The American Journal of Bioethics, 21(3), 56-74.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Skloot, R. (2017). The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks. Broadway Paperbacks.

Stake, R. E. (1983). Program evaluation, particularly responsive evaluation. In Madaus, G. F. (Ed.), Evaluation models: Viewpoints on education and human services (vol. 6, pp. 287-310). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-6669-7_17

Stake, R. E. (1975). Program evaluation, particularly responsive evaluation. Center for instructional research and curriculum evaluation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/0-306-47559-6_18

Stanford, F. C. (2020). The importance of diversity and inclusion in the healthcare workforce. Journal of the National Medical Association, 112(3), 247-249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2020.03.014

Taylor, A. (2018). Knowledge citizens? Intellectual disability and the production of social meanings within educational research. Harvard Educational Review, 88(1), 1-25.

Toombs, K. (1995). The lived experience of disability. Human Studies, 18(1), 9–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20011069

Vaughn, L. M., & Jacquez, F. (2020). Participatory research methods: Choice points in the research process. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.13244

Wallerstein, N. B., & Duran, B. (2006). Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice, 7(3), 312–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839906289376

Wesp, L. M., Scheer, V., Ruiz, A., Walker, K., Weitzel, J., Shaw, L., , Kako, P., & Mkandawire-Valhmu, L. (2018). An emancipatory approach to cultural competency: The application of critical race, postcolonial, and intersectionality theories. Advances in Nursing Science, 41(4), 316-326. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000230