11 An Interactive Training Model to Promote Cultural Humility For Early Childhood Professionals

Anjali G. Ferguson; Chimdindu Ohayagha; and Jackie Robinson Brock

Ferguson, Anjali G.; Ohayagha, Chimdindu; and Robinson Brock, Jackie (2023) “An Interactive Training Model to Promote Cultural Humility For Early Childhood Professionals,” Developmental Disabilities Network Journal: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 12.

Plain Language Summary

Professionals who work with young children need to understand the impacts of racism on development. The authors developed two models to address this need. One training model was held over the course of 6 months and contained three sessions. The other training model was a brief training that occurred one time. Both training models helped professionals understand their own biases; however, the three-session training showed greater understanding of bias. The training sessions were interactive and gave participants resources to use in their setting. This article compares the results of the two training models.

Abstract

The disability population in the U.S. has grown, with an estimated 2.6 million households having at least one child with a disability in 2019. Racially minoritized children disproportionately represent disability categories with Black and Indigenous children being over diagnosed with emotional disturbance disorders. Further, minoritized children often experience greater rates of complex trauma and this exposure significantly impacts minoritized children’s mental health. A hurdle to accurate identification and treatment of trauma/racial trauma for minoritized families is the availability of quality services which is impacted by bias in healthcare and systemic barriers. Pre-service trauma-informed training serves as an avenue to educate healthcare providers, paraprofessionals, and policymakers about disparities in healthcare. To address this concern a pilot training series was created for 0-6 professionals across the state. This 3-part training series was designed for Head Start Health Specialists, Mental Health Specialists, or Education Specialists and designed to provide interactive information on implicit biases, social determinants of health, the intersectionality of racism, and trauma to improve culturally-responsive care and address disparities. This longer, experiential training model was compared to a brief, short-term model focused on social determinants of health and an introduction to trauma-informed care. Preliminary qualitative and quantitative results demonstrate participants’ racial attributional shifts and a commitment to incorporating culturally responsive efforts in their communities and workplaces following the long-term experiential model. Overall, results demonstrate a successful training model for early childhood practitioners’ understanding of diversity, equity, and inclusion, and have aided in developing a system that supports diversity. This underscores the need for interactive training for paraprofessionals that provide psychoeducation that also addresses individual understanding of implicit biases/roles within systems. This training can be utilized with other early childhood professionals to build a culturally responsive system of care for children 0-6.

Introduction

The disability population in the U.S has grown, with an estimated 2.6 million households having at least one child with a disability in 2019 (Young, 2021). Between 2009-2017, about 1 in 6 (17%) children aged 3–17 years were diagnosed with a developmental disability (Zablotsky et al., 2019). Children from low-resource homes are more likely to have a disability (6.5%) compared to children living above the poverty threshold (3.8%; Young, 2021). Recent studies show that American Indian and Alaska Native children displayed the highest rate of childhood disability of all racial groups, at 5.9% in 2019, followed by Black and multiracial children (5.1% and 5.2% respectively; Young, 2021). It is important to note that this increase in disability prevalence among racially minoritized children, particularly those from low-resource homes, is not directly informed by a child’s racial/ethnic identity. Extant research demonstrates other contextual and systematic factors underlie these disparities.

Racial and ethnic healthcare disparities are defined as differences in the quality of healthcare provided to patients of color compared with White patients (Goins et al., 2013). Racial and ethnic disparities are influenced in part by an individual’s biases regarding racial attribution. Racial attribution refers to whether people attribute differences between racial groups to either dispositional (e.g., related to the individual) or situational factors (related to environment). For example, people may attribute racial differences in test performance to organic intellectual deficiencies (dispositional) or inequalities in access to quality education (situational; Trahan & Laird, 2018). These attributions or attitudes can inform how someone responds consciously and subconsciously towards minoritized groups. In essence, they are biased attitudes about race and ethnicity. Over the past 10 years, several studies have documented racial and ethnic disparities in children with disabilities (Durkin et al., 2017). Social determinants of health (SDOH) are a term used to describe the various life conditions that impact one’s health outcomes, including experiences of racism and racial trauma (Navarro, 2009). Racially minoritized children disproportionately represent disability categories, with Black and Indigenous children being over diagnosed with emotional and learning disabilities (Oswald & Coutinho, 2001; Patton, 1998). Additionally, minoritized children often experience greater rates of complex trauma (Horowitz et al., 1995), which ultimately impacts their mental health outcomes (Flannery et al., 2004).

Studies demonstrate that systematic and pervasive bias in the treatment of minoritized groups contributes to a substandard level of care (Baily et al., 2017; Institute of Medicine, 2003). Despite the passing of the 1960s civil rights laws, barriers to healthcare utilization for Black individuals still exist (Smith, 1999), with more covert forms of racism maintaining systemic inequities (Ahlberg et al., 2019). The lack of cultural competence in healthcare is often cited as the primary facilitator of health disparities (Horner et al., 2004). The historical roots of racism in healthcare illustrate that health disparities are not singularly a result of an individual’s behaviors but are a problem that is rooted in organizational/institutional structures and practices (Byrd & Clayton, 2000, 2001). Researchers argue that a systems-change approach is necessary to reduce healthcare disparities (Griffith et al., 2007).

One frequently utilized approach to addressing racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare is individual-level reeducation (Griffith et al., 2007). Research demonstrates that cultural awareness workshops improve intermediate outcomes such as knowledge, attitudes, and skills of health professionals, patient-provider communication, and patient satisfaction over time (Shepherd, 2019). Training in cultural competency has become the avenue in which organizations address and educate healthcare providers on disparities (Beach et al., 2005). However, recent investigations now move away from the cultural competence perspective and towards cultural humility and responsiveness. This redirection deviates from an implied “mastery” or competence of cultural nuances toward a lifelong, active, and fluid reflective process that emphasizes individual acknowledgment and accountability of power imbalances between patient and provider (Cox & Simpson, 2020).

A hurdle to accurate identification and treatment of trauma and/or racial trauma for minoritized families is the availability of quality culturally responsive and humble services. This is further impacted by bias in healthcare and subsequently creates intentional and unintentional systemic barriers to care. To effectively address systemic needs, practitioners must adopt a preventative approach early in developmental care and target universal settings by providing psychoeducation and cultural responsiveness training. To date, there is a dearth of current literature addressing social determinants of health through a long-term experimental method. Generally, diversity-informed workshops are presented in short durations, from a single session of 1-2 hours to a full day across multiple sessions. Researchers critique the efficacy of short-term workshops, noting that workshops are rarely long enough to absorb meaningful information that can be implemented into practice. Short-term methods have been regarded as the “museum approach,” whereby attendees are briefly exposed to a catalog of historical and cultural information without subsequent follow-up and re-engagement of information (Sheppard 2019). Further, a recent investigation identified that exposure to disparity information alone is insufficient for behavioral change. These findings highlight the need for training models that emphasize an emotional response in participants (Skinner-Dorkenoo et al., 2022). A study on 56 healthcare professionals across various disciplines showed that most providers desire more frequent, long-term, and mandatory cultural awareness training (Sheppard et al., 2019) to further facilitate the ongoing exposure and understanding of cultural nuances.

Method

The current investigation utilized data collected pre- and post-training to examine the efficacy of long-term experiential models compared to brief equity training models. We hypothesized that exposure to trauma-informed equity content over a longer period of time that included experiential activities and applied discussions would evidence a greater impact on racial attributional change than brief, less experiential training. By understanding the nuanced mechanisms and modalities in which racial attribution can significantly be influenced, we can better inform training approaches that address meaningful systemic understanding of disparities and promote individual application of culturally informed strategies. The study is a pilot investigation that utilized mixed quantitative and qualitative methods to collect data on participant knowledge, attitudes, and planned behavioral changes as it relates to cultural responsiveness and humility in early childhood professionals.

Procedures

To address the need for culturally responsive practices for professionals the University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCEDD), the Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities (LEND) program, and the Child Development Clinic at the Children’s Hospital of Richmond partnered to develop a pilot training series for professionals working with children birth through age 6 and their families across the state. This 3-part training series was sponsored by Head Start State Collaboration Office in partnership with the Early Childhood Mental Health Virginia initiative (a jointly funded initiative at the UCEDD). The training was designed for Head Start Health Specialists, Mental Health Specialists, or Education Specialists. The training was provided in an interactive format and included information on implicit biases, social determinants of health, the intersectionality of racism, and trauma with the ultimate goal of improving culturally responsive care and addressing disparities. The Diversity Informed Tenets for Work with Infants, Children, and Families were incorporated into the training.

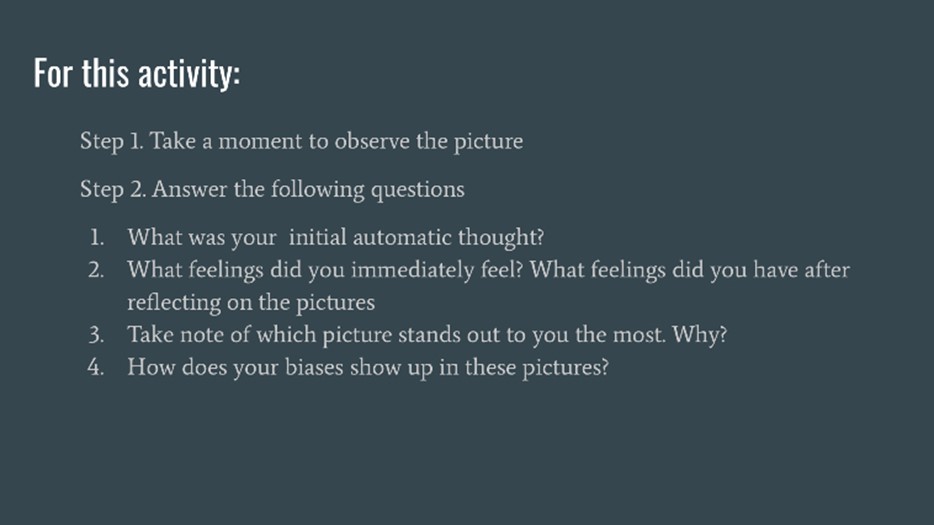

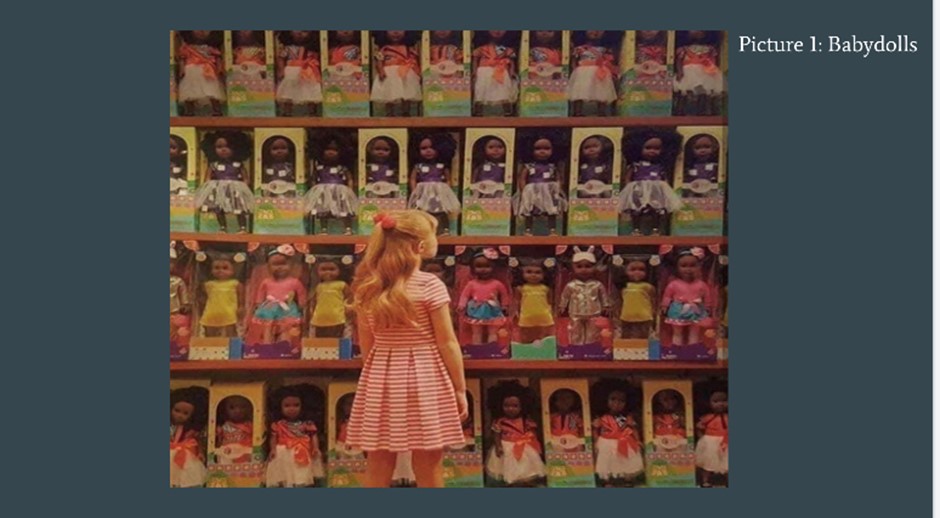

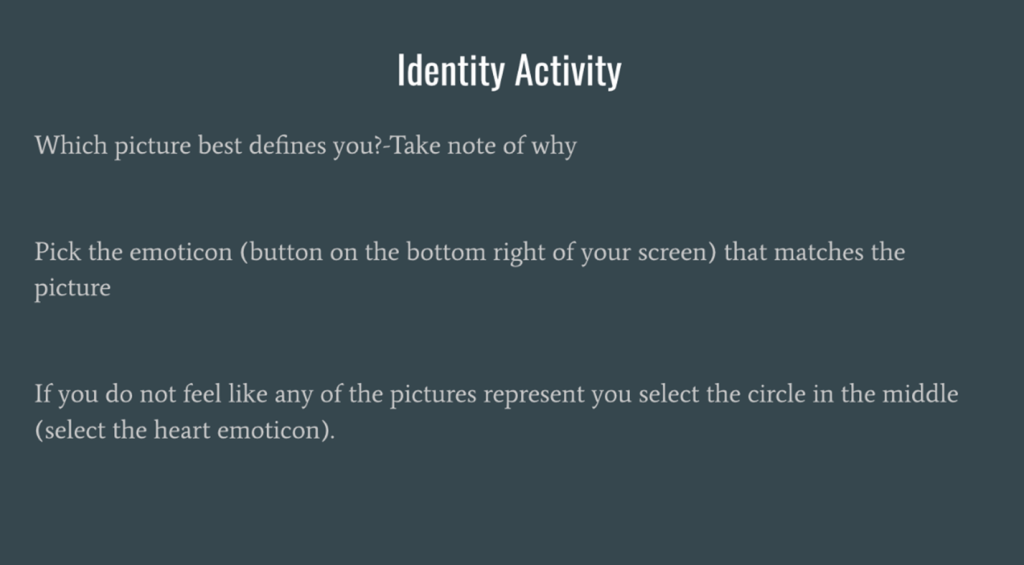

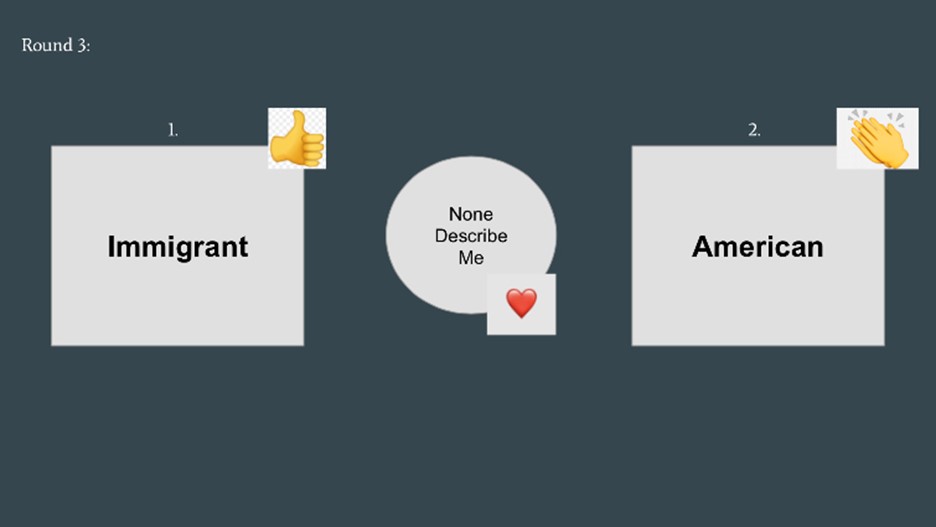

Two cohorts completed the training. Cohort One participated in a 3-part course. Cohort Two was a condensed course. The details of the courses that include goals and tenets addressed can be found in Table A1 in Appendix A The Tenets were intentionally chosen as a guiding framework because of the focus on infants, children, and reflective components. A defining component of the training series included reflective and experiential processes at each workshop (see Figures 1 and 2), which encouraged individual processing and application of content presented.

Figure 1 Experiential Activity: Implicit Bias Images

Figure 1 Experiential Activity: Implicit Bias Images

Figure 2 Experiential Activity; Identity Exploration

The first cohort participated in a workshop that was provided over the course of 9 months (every 3 months). It was estimated that each workshop session would be about 3 hours of training and activities. The workshop series was provided virtually. Participants engaged in dyadic discussion and presentation in a large group format. Throughout the series, participants completed experiential activities and case studies in small breakout groups facilitated by the trainers. A website was created with resources related to the workshop. Recordings of the workshop were posted to the site.

A pretest was used at the time of registration and contained the Modern Racism Scale (MRS). After workshop 1, a posttest was sent that included the MRS and qualitative assessments of the content presented. Of the 12 participants, 7 completed the posttest. Upon completion of the evaluation. participants received a certificate of participation. The measurements were not anonymous. The evaluation was modified after the first workshop to include demographic data (i.e., DOB, gender, race/ethnicity) and the inclusion of the Symbolic Racism Scale (SRS) to address criticisms of the MRS. After participants completed Workshop 2 and 3, they received the same posttest evaluation. A follow-up survey was sent 6 months after completion of Workshop 3. In addition, a survey was sent to participants who registered for the training series but did not attend a workshop.

Cohort Two of this study included a partnership with The Virginia Head Start Association to provide a condensed version of the aforementioned workshop series for their annual conference attendees. The condensed workshop consisted of a 1.5-hour presentation offered virtually on brief introductions to implicit bias, social determinants of health, and trauma-informed care. Given the large population and limited time, information was presented primarily in a didactic lecture format through Zoom and with fewer opportunities for experiential learning and processing (as done in the pilot 3-course series). In this workshop, participants attended a 55-minute lecture and then completed a 15-minute case study followed by a brief opportunity for questions.

Because of organizational barriers, pre-workshop data were not collected from Cohort Two. Participants were invited to complete a post-workshop survey following the presentation. Twenty-one of the 100 participants completed the assessment, which included the SRS, MRS, and qualitative feedback. Pretest data were not collected from this sample because of organizational/systemic barriers.

Participants

Participants in both the short- and long-term training sessions registered voluntarily for the training workshops. Workshop participants in the longer session were limited to Head Start Education Specialists, Health Specialists, and/or Mental Health Specialists. The State Head Start Association sent the registration flier and were responsible for recruitment. In Cohort One, 31 participants completed the pre-workshop survey prior to part 1 of the training series. Twelve participants completed workshop 1, four completed workshop 2, and five completed workshop 3. Participation in workshop 1 was required for participation in workshops 2 and 3. Unfortunately, demographic data were not collected at workshop 1. Professional titles of those completing the post-workshop survey after workshop 1 included program coach, educational specialist, family advocate, director, child development specialist, and health services administrator. At workshop 2, the age of participants completing the survey ranged from 37 to 61, with 100% identifying as cisgender female, 100% White, and 33% reporting Native American/Indigenous heritage. Last, at workshop 3, the age of participants ranged from 40 to 82 and gender included 75% identifying as cisgender female, 25% cisgender male, 75% White, 25% Black/African American, and 25% Native American/Indigenous.

Cohort Two consisted of participants from the 2022 Virginia Head Start Association conference. Over 100 participants attended a 1.5-hour virtual didactic workshop, which consisted of a condensed presentation of information and activities provided in the larger, three-part series. Of the 100 participants, 21 elected to complete a post-workshop survey. Of these reporting participants, ages ranged from 25-73 years. Forty percent identified as Black/African American, 45% as White, and 5% as Asian/Asian American/Pacific Islander. Ten percent of participants identified as Latino/Latinx/Hispanic. Regarding gender identification, 70% identified as cisgender female, 5% cisgender male, 5% preferred not to report their identification, and 20% indicated that their identification status was “not listed.” Professional titles of those responding from the conference included director of family engagement, early intervention coordinator, education manager, family advocates, family development specialists, services coordinator, health manager, nutrition coordinator, and registered nurse.

Measures

Quantitative Data

Modern Racism Scale

(MRS; McConahay et al., 1980). A 7-item measure of racial attitudes on a 5-point Likert scale (agree strongly to disagree strongly). The original measure was created to measure the cognitive components of covert racial attitudes towards Black individuals. Items were adapted in the current investigation to capture the current socio-political climate and a greater breadth of diversity in assessment by changing “Black people” to “Black Indigenous, and People of Color” (i.e., “Black, Indigenous, and People of Color [BIPOC] people have more influence upon school desegregation plans than they ought to have”). Researchers have identified reliability and test-retest stability. Although psychometric properties support the use of the measure, the MRS has received criticism from researchers who raise questions regarding the conceptual distinctiveness of the questionnaire; therefore, the SRS measure was also selected following recruitment in the first cohort.

Symbolic Racism Scale

(Henry & Sears, 2002). A 4-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 4 = Strongly Agree) measures an individual’s attitudes/beliefs about racism across four domains: (1) work ethic and responsibility for outcomes, (2) excessive demands, (3) denial of continuing discrimination, and (3) undeserved advantage. The 8-item scale was developed to assess covert attitudes representative of racism directed towards Black communities. The scale has demonstrated reliability and construct validity (Sears & Henry, 2005).

Qualitative Data

Qualitative investigation affords a culturally responsive approach to data collection by affording respondents an opportunity to provide responses informed by their cultural identity and context. The current investigation utilized the Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR), which is defined by an inductive rationale to define the outcomes. The current investigators represented the judges of the research data and included a doctoral psychologist, a masters level social worker, and a masters level psychologist. Research team members varied on racial identification, age, and educational attainment, which offers variability in perspectives. The external audit was conducted by a doctoral level clinical psychologist.

Domains were created to summarize core beliefs as related to outcomes of the presented data. The current investigation was interested in examining individual responses to the provided workshops, application of information presented, and whether changes were observed in racial attitudes and attributions.

Participants in the first cohort were provided the following questions pre-workshop: “How do you plan to use the information you learn in this training series”; “Please identify 5 (maximum) things you want to learn from this training series”; and “Is there anything else you’d like us to know”? Participants across both samples provided responses to the following qualitative questions post-workshop; (1) Name three of the things you learned as a result of participating in the training series; (2) How do you plan to use what you’ve learned from this training series in your practice; (3) Has the training course dealt with some of your difficulties or weaknesses in developing anti-racist projects and practice? (4) After this training, what do you feel are your strengths and weaknesses in relation to Inclusion and Group Initiatives; (5) How do you think future training can be improved; (6) What information do you feel you still need; (7) Is there anything else you’d like us to know?

Results

Group Comparisons

Independent t tests were conducted to assess mean differences by type of workshop completed. A mean difference trending towards significance was found between participants who completed the 3-part workshop series and those completing the brief, fundamentals course on the MRS, t(23) = -1.13, p ≤ .1. Upon completion, those in the longer course reported a significantly lower mean score (M = 1.21, SD = .27) than those in the brief training (M = 1.75, SD = .92). Greater mean scores on the MRS are indicative of negative racial attribution bias; therefore, those in the longer course exhibited lower racial attribution biases following their training. Mean differences were also found to trend toward significance on the SRS, t(23) = 5.88, p ≤ .06. Participants completing the longer workshop series evidenced a significantly greater mean score (M = 31.50, SD = .5) than participants in the brief training (M = 25.70, SD = .41). Greater scores on the SRS are representative of lower racial attributional biases.

Qualitative Analyses

Listed below are qualitative data analyses of Cohort One followed by Cohort Two. Details regarding analyses are shown in Table 1 for Cohort One and in Table 2 for Cohort Two. For Cohort One (long-term training series), a total of 33 respondents were analyzed pre-workshop on the aforementioned provided questions. Six participants were examined following workshop 1, three participants following workshop 2, and four participants following workshop 3. The research team analyzed the qualitative data using the CQR method. Using this process, the following domains were identified in the pre-workshop survey: Gain Knowledge, Understand Racial Trauma, and How to Apply Information. Post-workshop 1 data identified the following domains: Awareness of racism and Introspection on implicit bias. Post-workshop 2 identified the following domain: Advocacy. Workshop 3 domains included: Understanding of trauma/racial trauma and overall satisfaction with the training series.

| Domains | Representative statements | Participants (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-workshop Survey | ||

| Gain knowledge |

|

67 |

| Understand racial trauma |

|

27 |

| How to apply information |

|

33 |

| Post-workshop 1 | ||

| Awareness of racism |

|

83 |

| Introspection on implicit bias |

|

100 |

| Advocacy |

|

67 |

| Post-workshop 2 | ||

| Understanding trauma/racial trauma |

|

75 |

| Overall satisfaction |

|

100 |

Pre-Workshop Survey: Cohort 1

Gain Knowledge

This domain was characterized by 67% of participants reporting a desire to learn my information regarding equity and inclusion practices as they relate to systemic change.

Understand Racial Trauma

The second domain was informed by individuals who presented with a desire to further understand racial disparities, trauma-formed care, and how culture/race-based experiences can be informed by trauma. Twenty-seven percent of participants identified these topic areas as a strong desire of focus and participation in the course.

How to Apply Information

Thirty-three percent of participants reported a desire to better understand skills associated with trauma-informed care and application to work with children and families.

Post-Workshop 1: Cohort 1

Awareness of Racism

Following the first workshop 83% of participants reported a greater understanding of current presentation of systemic racism and impacts on diverse groups.

Introspection on Implicit Bias

The first workshop heavily focused on experiential activities informing and applying implicit biases. 100% of respondents reported a greater understanding of hidden and unknown biases that were previously unexamined. Respondents noted that the introspection was useful in understanding their own roles in the content.

Post-Workshop 2: Cohort 1

Advocacy

Workshop 2 presented information about Social Determinants of Health and impacts on health and mental health outcomes. The series ended with a call to action and suggestions on how to implement the knowledge. Following the second workshop 67% reported a desire to engage in greater advocacy efforts in their communities.

Understanding Trauma/Racial Trauma

Workshop 3 culminated with an introduction to trauma-informed care from a racially conscious perspective 75% reported a greater understanding of racial trauma and a desire to implement these principles in their individual work.

Overall Satisfaction: Cohort 1

The series ended with an open-ended question requesting participants provide information on “anything else” they would like to share. 100% reported significant satisfaction with the training series. See Table 1 for example responses to each domain.

There were some participants in Cohort One who registered for the training series but didn’t attend the workshop. A survey was developed and sent to these participants to understand more about why they registered but did not attend. Three participants responded to the survey. Most participants indicated that they had work conflicts that prevented them from attending. All respondents were interested in participating in future workshops.

Cohort 2 (Brief Workshop)

A total of 21 participants were analyzed on the aforementioned post-workshop responses. As a reminder, pre-workshop data were not collected with this sample. The following domains were identified through the CQR method: An understanding that systemic racism is current, awareness and desire to utilize training materials with colleagues, desire for a longer training, and content rejection

An Understanding That Systemic Racism is Current

The first domain reflects that participants report an understanding that systemic racism and inequality remains today. 50% of responses identified their greatest takeaway from the course was recognizing how inequalities continue to impact an individual’s access and overall health outcomes.

Awareness and Desire to Utilize Training Materials with Colleagues

The second domain was characterized by reports from participants indicating a greater self-awareness from the training and a desire to disseminate this information with colleagues and those in their “networks.” Sixty-seven percent indicated that they will be taking this information back to their workplaces and reported responses indicative of self-reflection.

Desire for a Longer Training

Domain three represents a consistent response when asked how training can be improved. 50% of participants indicated a request for a longer training and desire for greater depth in the presented content.

Content Rejection

The fourth domain is defined by a rejection of the content presented. Although disapproval was a small percentage of the population (17%), several individuals reported a promotion of Eurocentric supremacist ideologies following the workshop. Table 2 includes example representative responses for each domain.

| Domains | Representative statements | Participants (%) |

|---|---|---|

| An understanding of systemic racism |

|

50 |

| Awareness and desire to utilize training materials with colleagues |

|

67 |

| Desire for a longer training |

|

50 |

| Content rejection |

|

17 |

Discussion

The current investigation examined a long-term experiential training model to a brief, single-session short-term training model. Participant racial attribution biases were assessed following each training model to determine the efficacy of longer-term, experiential workshops. Results from the current investigation, through both qualitative and quantitative analyses, demonstrates a trend towards significant shifts in racial attribution biases following a long-term training model and confirms hypotheses that short-term cultural responsiveness training are less effective.

Training about cultural responsiveness and humility often focuses on awareness building as opposed to attitudinal change. Attitudinal change is what ultimately leads to changes in practice. Qualitative and quantitative results from the long-term training pilot demonstrate participants’ attitudinal shifts and a commitment to incorporating culturally responsive efforts in their communities and workplaces. Participants noted that they enjoyed the interactive nature of the training, indicating a benefit to including interactive activities throughout training in this topic. This shows the need for an interactive training model that not only targets paraprofessionals and provides psychoeducation, but one that also informs individual understanding of implicit biases and roles within systems.

Limitations and Implications

Although promising results were indicated in the pilot study, a significant limitation of the current investigation included the sample size of participants in the long-term model over time and concerns related to attrition. This pilot investigation had a relatively small sample size. Despite this, data were trending towards significance. It is imperative that future investigations include use of this training model with a larger sample size to measure statistical significance.

Another limitation of the current investigation was attrition over the three-course model. Several reasons may inform these observations. First, given that the workshop was spread over the course of 9 months, the length of time between courses may have impacted participation. In addition, participants reported feeling overwhelmed with the COVID-19 pandemic and felt that they had personal stressors that impacted attendance. In addition, participants indicated other demands that prevented them from attending the course. It would be useful to explore whether the content could be provided online for the participant to complete before coming to the workshop(s) for deeper discussion.

Last, because of organizational barriers and recent state-level policy changes that impacted diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, pre-workshop data were not obtained from the short-term training model. This presents a limitation in the current investigation regarding group comparisons; however, qualitative and quantitative analyses post-workshop emphasize the differences between groups. Future investigations should work towards obtaining pre-workshop data for all cohorts.

Overall, the long-term training pilot has demonstrated a successful training model that helped early childhood practitioners develop a shared understanding of diversity, equity, and inclusion, and aided in developing a system that supports diversity. The training can be utilized with other early childhood practitioners to build a culturally responsive system of care for children birth through 6 years old.

References

Ahlberg, B. M., Hamed, S., Thapar-Björkert, S., & Bradby, H. (2019). Invisibility of racism in the global neoliberal era: Implications for researching racism in healthcare. Frontiers in sociology, 4(61). DOI: 10.3389/fsoc.2019.00061

Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agénor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet, 389(10077), 1453–1463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

Beach, M. C., Price, E. G., Gary, T. L., Robinson, K. A., Gozu, A., Palacio, A., Smarth, C., Jenckes, M. W., Feuerstein, C., Bass, E. B., Powe, N. R., & Cooper, L. A. (2005). Cultural competence: A systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Medical Care, 43(4), 356–373. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96

Byrd, W. M., & Clayton, L. A. (2000). An American health dilemma. Routledge.

Byrd, W. M., & Clayton, L. A. (2001). Race, medicine, and health care in the United States: A historical survey. Journal of the National Medical Association, 93(Suppl. 3), 11S–34S.

Cox, J. L., & Simpson, M. D. (2020). Cultural Humility: A proposed model for a continuing professional development program. Pharmacy, 8(4), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8040214

Coutinho, M. J., & Oswald, D. P. (2000). Disproportionate representation in special education: A synthesis and recommendations Journal of Child and Family Studies, 9(2), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009462820157

Durkin, M. S., Maenner, M. J., Baio, J., Christensen, D., Daniels, J., Fitzgerald, R., Imm, P., Lee, L. C., Schieve, L. A., Van Naarden Braun, K., Wingate, M. S., & Yeargin-Allsopp, M. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder among us children (2002-2010): Socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities. American Journal Of Public Health, 107(11), 1818–1826. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304032

Ferguson, A., & Garcia, J. (2020). Cultural values assessment. Parenting culture: The resource for parenting in a multicultural world. https://parentingculture.org/

Fiscella, K., & Sanders, M. R. (2016). Racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of health care. Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021439

Flannery, D. J., Wester, K. L., & Singer, M. I. (2004). Impact of exposure to violence in school on child and adolescent mental health and behavior. Journal of Community Psychology, 32(5), 559-573.

Griffith, D. M., Mason, M., Yonas, M., Eng, E., Jeffries, V., Plihcik, S., & Parks, B. (2007). Dismantling institutional racism: Theory and action. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39(3-4), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9117-0

Henry, P., & Sears, D. (2002). The Symbolic Racism 2000 Scale. Political Psychology, 23(2), 253–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00281

Horner, R. D., Salazar, W., Geiger, H. J., Bullock, K., Corbie-Smith, G., Cornog, M., Flores, G., & Working Group on Changing Health Care Professionals’ Behavior. (2004). Changing healthcare professionals’ behaviors to eliminate disparities in healthcare: What do we know? How might we proceed? The American Journal of Managed Care, 10(SP12-19).

Horowitz, K., Weine, S., & Jekel, J. (1995). PTSD symptoms in urban adolescent girls: Compounded community trauma. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34(10), 1353-1361.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care (Smedley, B. D., Stith, A. Y., & Nelson, A. R. Eds.). National Academies Press.

McConahay, J. B. (1986). Modern racism, ambivalence, and the Modern Racism Scale. In J. F. Dovidio & S. L. Gaertner (Eds.), Prejudice, discrimination, and racism (pp. 91–125). Academic Press

Navarro, V. (2009). What we mean by social determinants of health. International Journal of Health Services, 39(3), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.2190/HS.39.3.a

Patton, J. M. (1998). The disproportionate representation of African Americans in special education: Looking behind the curtain for understanding and solutions. The Journal of Special Education, 32(1), 25-31.

Sears, D., & Henry, P. (2005). Over thirty years later: A contemporary look at symbolic racism and its critics. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 37, 95-150

Shepherd, S. M. (2019). Cultural awareness workshops: Limitations and practical consequences. BMC Medical Education, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1450-5

Skinner-Dorkenoo, A. L., Sarmal, A., Rogbeer, K. G., André, C. J., Patel, B., & Cha, L. (2022). Highlighting COVID-19 racial disparities can reduce support for safety precautions among White US residents. Social Science & Medicine, 301, 1-9.

Smith, D. B. (1999). Health care divided: Race and healing a nation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Trahan, A., & Laird, K. (2018). The nexus between attribution theory and racial attitudes: A test of racial attribution and public opinion of capital punishment. Criminal Justice Studies: A Critical Journal of Crime, Law & Society, 31(4), 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478601X.2018.1509859

Young, N. (2021). Childhood disability in the United States: 2019. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2021/acs/acsbr-006.pdf

Zablotsky, B., Black, L. I., Maenner, M. J., Schieve, L. A., Danielson, M. L., Bitsko, R. H., Blumberg, S. J., Kogan, M. D., & Boyle, C. A. (2019). Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the US: 2009–2017. Pediatrics, 144(4), 1-11.

Appendix

| Key activities | Diversity informed tenets addressed |

|---|---|

| Goal: Improve service-provider understanding of SDOH impacts on underrepresented groups in order to increase the quality of care | |

| Course 1: Understanding our implicit biases | |

| Attendees will complete online Implicit Association Test and implicit bias training. They will then attend a provided debrief/process group to discuss results and complete additional activities designed to promote introspection of internal biases.

Activities to include: Group cultural identification task with unconventional representational images of groups. Participants asked to pick which group best represents them over various topics. The conflicting images and group engagement encourage discussion of stereotypes and underlying subconscious themes that may promote bias. |

1. Self-awareness leads to better service for families

3. Work to acknowledge privilege and combat discrimination |

| Course 2: Reconceptualizing social determinants of health | |

| An introduction to the notion of SDOH. Understanding the impact of larger systems on mental health and access to care. Begin to build awareness of the complexities of systemic racism and how we must reconceptualize our practices to think more holistically. Course will include case examples and activities to promote application of knowledge | 3. Work to acknowledge privilege and combat discrimination

4. Recognize and respect non-dominant bodies of knowledge 5. Honor diverse family structures 6. Understand language can hurt or heal |

| Course 3: An introduction to racial trauma and applications to care, healthcare, and policy | |

| What is racial trauma? How is racial trauma impacted by SDOH and how do we modify existing trauma- informed principles to become more racially and culturally competent?

Critique our current models and assessments of care as a primarily Eurocentric lens that is impacting treatment outcomes and adherence. Discuss ways to adopt culturally responsive principles to increase trauma-informed care for diverse groups. Understand the history of medical and intergenerational trauma and its impacts on marginalized groups’ willingness to engage in care. Course will include case examples and activities that facilitate the application of knowledge. Participants will be introduced to the Cultural Values Assessment (Ferguson & Garcia, 2020). |

4. Recognize and respect non-dominant bodies of knowledge

5. Honor diverse family structures 6. Understand language can hurt or heal 9. Make space and open pathways |

| Fundamentals course: A brief introduction to SDOH and trauma/racial-trauma informed applications to care | |

| What are Social Determinants of Health and how do they inform current healthcare, education, mental health outcomes. Why must we reconceptualize these understandings? What is trauma-informed care? Limitations of existing trauma interventions and a discussion of the need to include racial trauma principals to care. Intro to suggestions on how to implement principals to care. | 4. Recognize and respect non-dominant bodies of knowledge

5. Honor diverse family structures 6. Understand language can hurt or heal 9. Make space and open pathways |