13 Advancing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Developmental Disabilities: The Essential Role of Leadership for Cultural and Linguistic Competence

Tawara D. Goode; Oluwatosin Ajisope; Sharonlyn Harrison; Betelhem Eshetu Yimer; Deborah Perry; and Wendy Jones

Goode, Tawara D.; Ajisope, Oluwatosin; Harrison, Sharonlyn; Yimer, Betelhem Eshetu; Perrry, Deborah; and Jones, Wendy (2023) “Advancing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Developmental Disabilities: The Essential Role of Leadership for Cultural and Linguistic Competence,” Developmental Disabilities Network Journal: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 14.

Plain Language Summary

Diversity, equity, and inclusion should not be seen as problems. Diversity, equity, and inclusion should be seen as opportunities for all people, including persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD). A federal law for persons with IDD requires cultural competence. This law says cultural competence helps to respect a person’s culture and language. This law is the Developmental Disabilities Bill of Rights and Assistance Act, 2000. Cultural and linguistic competence or CLC help reduce disparities. CLC can help advance diversity and increase equity. There is a need for people with and without disabilities to take the lead to move CLC forward. The Georgetown University National Center for Cultural Competence created a Leadership Institute to meet this need. This article gives information about this national leadership institute.

Abstract

There is a clear and compelling need to approach equity, diversity, and inclusion not as problems to be solved, but rather as opportunities to be realized. The Developmental Disabilities Bill of Rights and Assistance Act of 2000, states the need for cultural competence, specifically to ensure that supports and services “are provided in a manner that assure maximum participation and benefit for persons with IDD.” Cultural and linguistic competence (CLC) are evidence-based or proven practices that reduce disparities, advance diversity, and promote equity. Achieving CLC requires strong and informed leadership to spark the necessary changes within systems, organizations, and practice. It requires responding effectively to race, ethnicity, culture, and other intersecting identities in leadership development and opportunities. There is a need for leaders with the commitment, energy, knowledge, and skills to do the hard work of advancing and sustaining CLC in systems, organizations, and programs that develop policy, provide supports and services, conduct research, and advocate with persons with IDD and their families. It is important that leaders have the insight, courage, and skill to step out in the forefront of this complex set of dynamics and be the force to gather the collective will to make change. There are two distinct yet related challenges that continue to confront the IDD network: (1) the lack of capacity across all aspects of the network to develop, nurture, and support people who are prepared to lead efforts that advance and sustain CLC; and (2) there are few members of racial, ethnic, and cultural groups, including people with disabilities from these groups, presently occupying or being groomed to become leaders and assume leadership positions network-wide.

Introduction

Achieving cultural and linguistic competence (CLC) requires strong and informed leadership to spark the necessary changes within systems, organizations, and practice. CLC requires responding effectively to race, ethnicity, culture, and other intersecting identities in leadership development and opportunities. There is a need for leaders with the commitment, energy, knowledge, and skills to do the hard work of advancing and sustaining CLC in systems, organizations, and programs that develop policy, provide supports and services, conduct research, and advocate with persons who have lived experience of intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and their families. It is essential that leaders have the insight, courage, and skill to step out in the forefront of this complex set of dynamics and be the force to gather the collective will to make change in IDD systems across the U.S., territories, and tribal nations.

There are four distinct yet related challenges currently confronting the network of persons with IDD and their families, organizations, and concerned constituents in the diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) space. Challenge 1. There is a lack of capacity across all aspects of the network to develop, nurture, and support a pool of people who are prepared to lead efforts that advance and sustain CLC and cultural diversity. Challenge 2. There are few members of racial, ethnic, and cultural groups, including persons with disabilities from these groups, presently occupying or being groomed to become leaders and assume leadership positions network-wide. Challenge 3. Members of the IDD network, and the larger disability community as well, continue to make strides in their efforts to advance diversity and inclusion. Yet the network lags far behind other fields because equity has not been defined (Braveman et al., 2018; Jones, 2018; National Association for the Education of Young Children [NAEYC], 2019), consensus has not been reached on exactly what equity means in the IDD space, and leadership to advance equity is lacking (Goode, 2020). Challenge 4. Advancing CLC and cultural diversity demand confronting the elephant in room—power differentials within the IDD network. There is considerable tension caused by the power imbalances between the demographic make-up (i.e., race, ethnicity, and disability) of those who have historically and/or are currently in leadership positions within the IDD network, and the need for change in the power structure to reflect leadership that has a greater degree of diversity based on race, ethnicity, culture, disability, and other intersecting identities. Leaders are needed to move beyond the rhetoric of we should be changing these dynamics to we are changing them now and for the future.

Leaders are needed who are able to address the entrenched challenges that are inherent in efforts to advance and sustain CLC: (a) orchestrating organizational change processes; (b) addressing institutional and personal resistance to change; (c) understanding and responding affirmatively to the dynamics of diversity; (d) confronting biases, stereotyping, discrimination, racism, ableism, and other “isms” that plague segments of the populations that reside in the U.S., territories, and tribal nations; (e) redefining the concept of inclusion to we all belong; and (f) advocating with underrepresented populations for equity across the IDD network. Advancing and sustaining CLC is the responsibility of all within the IDD network and should not be relegated as the primary obligation of people from racial and ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic white.

In response to these needs, Georgetown University National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC), in partnership with persons with IDD and their families, organizations, and stakeholders representing a broad sector of the IDD network, implemented the Leadership Institute from 2014-2020. The Leadership Institute was funded by a cooperative agreement from the Office on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, Administration on Disabilities, Administration for Community Living, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This manuscript will: (1) provide an overview of the Institute; (2) describe the evaluation outcomes of the 158 individuals who benefitted from their participation in the Institute’s Leadership Academy and 24 individuals who participated in the Disparities Leadership Academy; (3) cite the results of a 2022 follow-up study of Leadership Academy participants that asks Where are they now? (i.e., how participants are using the training, coaching, and mentoring they received and their current leadership roles); and (4) offer lessons learned, outcomes achieved, and as a result justifies an ongoing investment for CLC leadership within the IDD network as proven approaches to support diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Purpose

In response to these challenges, Georgetown University National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC) planned and implemented the Leadership Institute from 2014-2020. Funding for this project was from the Office on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (OIDD) Administration on Disabilities (AoD), Administration for Community Living (ACL), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Leadership Institute was conducted in partnership with persons with IDD and their families, organizations, and stakeholders representing a broad sector of the IDD network. The Leadership Institute was guided by a Wisdom Council composed of representatives of the aforementioned groups. This manuscript (1) provides an overview of the Institute; (2) describes the evaluation outcomes of the 158 individuals who benefitted from their participation in the Institute’s Leadership Academy and 24 individuals who participated in the Disparities Leadership Academy; (3) cites the results of a 2022 follow-up study of Leadership Academy participants that asks Where are they now? (i.e., how participants are using the training, coaching, and mentoring they received and their current leadership roles); and (4) offers lessons learned, outcomes achieved, and justifies an ongoing investment for CLC leadership within the IDD network as proven approaches to support diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Description of the Leadership Institute for Cultural Diversity and Cultural and Linguistic Competence: A Catalyst for Change on Networks Supporting Persons with IDD

The goal of the Leadership Institute was to increase the number and capacity of leaders to advance and sustain CLC and respond to the growing cultural diversity among people with IDD in the U.S., territories, and tribal nations. The Leadership Institute consisted of three major components designed to increase capacity and effect change: (1) Leadership Academies, (2) mentoring for IDD organizations and leadership academy graduates, and (3) open access virtual Learning and Reflection forums for the IDD network. Additionally, the NCCC received additional funding from ACL/AoD to (1) include a cohort of participants from State Independent Living Centers and Centers for Independent Living, and (2) conduct a Disparities Leadership Academy for six states and one territory.

Leadership Institute Faculty

The Leadership Institute faculty consisted of a core team of four interdisciplinary Georgetown University faculty members, subject matter experts and consultants, and mentors. The demographic makeup of the faculty included representation across diverse racial, ethnic, cultural, and other identity groups, and persons with lived experience of developmental disabilities—some of whom have intersecting identities. All faculty, subject matter experts and consultants, and mentors are knowledgeable and experienced in cultural and linguistic competence, diversity, equity, and inclusion in the IDD space.

Leadership Institute faculty used the definitions in Table 1 to undergird all activities—cultural competence, linguistic competence, and leadership. This definition of cultural competence complements the DD Act definition and offers a definitive conceptual framework and a solid evidence-base to guide its adoption and implementation. The definition of linguistic competence is not specifically referenced in the DD Act although addressing languages of persons with IDD is stated.

| Activity | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1. Cultural competence | Cultural competence requires that organizations: have a defined set of values and principles and demonstrate behaviors, attitudes, policies, and structures that enable them to work effectively cross-culturally; have the capacity to (1) value diversity, (2) conduct self-assessment, (3) manage the dynamics of difference, (4) acquire and embed cultural knowledge, and (5) adapt to diversity and the cultural contexts of the communities they serve; and incorporate these five elements in all aspects of policy making, administration, practice, service delivery, and systematically involve key stakeholders and communities. Cultural competence is a developmental process that evolves over an extended period. Both individuals and organizations are at various levels of awareness, knowledge, and skills along the cultural competence continuum (Goode et al., 2017). |

| 2. Linguistic competence | Linguistic competence is the capacity of an organization and its personnel to communicate effectively and convey information in a manner that is easily understood by diverse groups, including persons of limited English proficiency, those who have low literacy skills or are not literate, persons with disabilities, and those who are deaf or hard of hearing. Linguistic competence requires organization and provider capacity to respond effectively to the health and mental health literacy of populations serves. The organization must have policy, structures, practices, procedures, and dedicated resources to support this capacity (Goode et al., 2017). |

| 3. Leadership | Leadership is: (a) a set of personal attributes, qualities, and skills either intuitive and/or acquired that rouse and motivate others; (b) the ability of an individual to influence, motivate, and enable others to contribute toward the effectiveness and success of the organization of which they are members (House et al., 2004; Northouse, 2001). These definitions of leadership reinforce the value that being a leader is not limited to those persons who hold a high rank or position. One of the primary areas of focus of the Leadership Institute is to enhance self-efficacy of participants to effect change, which results in increased CLC and diversity within the IDD network. |

Leadership Academies

The NCCC adapted a proven curriculum, the Georgetown University Leadership Academy, © to the sociocultural contexts of the IDD network. Participants submitted applications and were competitively selected by a review team. The week-long academies were conducted by experienced Georgetown University faculty and consultants (with and without disabilities). All Academy participants engaged in a series of prework assignments that were designed to: (1) provide knowledge about CLC and disparities, (2) set the stage for the context of their leadership work in their agencies and communities, (3) create awareness of their leadership through self-assessment and reflection, and (4) prompt thought provoking opportunities to identify leadership challenges they face. Prework included webinars, completing the Leadership Profile Inventory and Implicit Association Test, assignment to write a self-identified leadership challenge, and pre-academy coaching. The Institute’s curriculum content areas are listed below, and the pedagogical methods are in Table 2. Experiential learning for all content areas embedded leadership within the contexts of CLC, IDD, and the socio-cultural climate in the US, territories, and tribal nations. Post-academy coaching was required for all participants to support their individual growth and implementation of their action plans and offered up to one year after completing their onsite training. Participants were also offered individual mentoring. All participants completed pre- and post-surveys.

Leadership Academy Curriculum

- Importance of collective vision and its power

- Determining the nature of challenges (technical and adaptive challenge framework)

- Identifying leadership styles and learning when and how to use them in different contexts

- How to keep people on task (leading the work)

- Resistance to change (both personal and among others)

- How to identify who you need to collaborate with and for what purpose

- How to understand the impact of your behavior on others (Leadership Profile Inventory)

- Differentiating leadership, management, and advocacy

- The difference between formal and informal leadership

- The dynamics of power (power over, power to, power within, power with)

- Risk taking and how to assess what risks you are willing to take

- The importance of personal self-care (strategies and taking the time to actually take care of self)

| Peer group process | Lecturettes |

|---|---|

| Onsite coaching | Small and large group problem solving |

| Journaling | Dialogue groups on CLC, disparities, other participant-generated topics |

| Interactive exercises | |

| Case study |

Organizational Mentoring

Leadership Institute faculty provided mentoring support for five organizations in their journeys to increase CLC—efforts to recruit and retain diverse staff, faculty, and members, and engage culturally diverse constituents. Institute faculty tailored mentoring to the stages of organizational development and the unique interests and needs related to cultural diversity and CLC of each organization. These included but not limited to, professional development and in-service training, presentations for national conferences/meetings, individual consultation to leadership teams, and technical assistance (i.e., developing language access plan, policy reviews, conducting interest and needs assessment, and aligning organizational values with practices with cultural diversity and cultural and linguistic competence, and organizational and culture change theories and approaches). Participating organizations throughout all years of the project were the Association of University Centers on Disabilities, National Disability Rights Network, National Association of Councils on Developmental Disabilities, Self-Advocates Becoming Empowered, and Family Voices.

Learning and Reflection Forums

The forums were a series of web-based learning resources designed to: address the unique challenges encountered by those seeking to lead or leading cultural diversity and CLC; and share experiences, strategies, and practices. Each forum had capacity for up to 300 participants and featured subject matter expertise and experiential knowledge of organizations, programs, persons with lived experience both from within and outside of the IDD network. Forums used didactic and interactive learning approaches (i.e., lecturettes, polling questions, chat feature, Q&A, and self-reflection focused on leadership). Forums offered relevant practices, research findings, practical application of concepts and theories by sharing their on-the-job experiences as change agents and leaders. To ensure access and facilitate dissemination to a broad audience, each forum was recorded and archived on the Leadership Institute website.

Wisdom Council

The Leadership Institute’s structure included a 15-member group designed to provide guidance and sage counsel about all facets of the Institute’s activities. The Council met twice annually via conference call/webinar in the fall and spring. Members of the Council provided insight and recommendation on curriculum adaptation, topics for the Learning and Reflection Forums, dissemination, evaluation, and some Council members served as mentors. Members of the Wisdom Council represented diverse racial, ethnic, and other identity groups; persons with lived experience of intellectual, developmental, and other disabilities and their families; and geographic regions across the U.S. and tribal nations.

Disparities Leadership Academy

The overall goal of the Disparities Leadership Academy was to increase the capacity of seven ACL/OIDD-funded programs to lead efforts within their state or territory to address disparities affecting individuals with IDD and their families. Participating states and territories were competitively selected through an application process conducted by ACL/OIDD with input from NCCC faculty. The states and territories were required to focus specifically on disparities experienced by persons with IDD and their families such as but not limited to race, ethnicity, intersecting cultural, gender, sexual orientation identities, languages spoken, geographic locale, socioeconomic status. Each team was composed of the Developmental Disabilities Council, Disability Rights (Protection and Advocacy), and University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities. Participating states and territories, selected by ACL/OIDD were Arizona, Idaho, Michigan, Puerto Rico, South Dakota, Texas, and Wisconsin. The Leadership Academy pre-work, curriculum, and pedagogical methods and experiential learning were adapted to the unique goal of disparities reduction and for each team to identify and develop a disparities action plan for presentation and “buy in” within their states and territory.

Theoretical Underpinnings for the Leadership Institute

Guiding the work of the Leadership Institute is a theoretical framework based on the science of adult learning principles. Specifically, the theory of planned behavioral change posits a complex mix of attitudes and beliefs that predict the extent to which an individual will learn and exhibit a new behavior (Ajzen, 1991). These are described in the model as: (1) normative beliefs—an individual’s beliefs about the way the world should be; (2) control beliefs—the presence of internal or external factors that may facilitate or hinder performance of the behavior; and (3) behavioral beliefs—their subjective judgement of the likelihood that the behavior will produce a given outcome. Together, these form the building blocks of adult behavior change.

The Leadership Academy is the most immersive element of the Leadership Institute and designed to have the greatest potential to result in significant changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. Therefore, our evaluation efforts focused on short- and longer-term impacts on these participants. By providing experiential learning opportunities, the Leadership Academy helps challenge and shape participants’ normative and behavioral beliefs. Through continued coaching, participants also received the reinforcement and support that is necessary to help them develop the control beliefs that enable them to take the lessons they learn into their workplaces and communities and implement them effectively. The addition of optional mentoring helped participants apply a leadership lens to their career trajectories was also important to sustaining change over time.

Design and Measures

The Leadership Institute’s evaluation team were faculty and staff from the Georgetown University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (GUCEDD). The evaluation team designed and implemented an iterative mixed-methods evaluation to gather impact data on the major components of the Leadership Academy, which was presented to the Wisdom Council for their review and input. Three main evaluation strategies were used:

(1) Fidelity of Implementation

A summative evaluation was completed on-site on the last day of the Leadership Academy. This tool contained a mix of quantitative and open-ended questions that assessed the quality of implementation, immediate impact of specific activities, and solicited initial insights about personal growth and change during the four-day Leadership Academy.

(2) Changes in Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors

A baseline and follow-up survey that was administered at the beginning and end of the onsite Leadership Academy assessed short-term gains in knowledge and change in participants’ views of themselves as leaders. The follow-up was administered within a week of participants returning home from the Leadership Academy. Of note, in past Leadership Academies conducted by our team focused on children’s mental health, we observed a tendency for participants to over-estimate their initial skills and knowledge. To adjust for this, the evaluation team introduced a “retrospective posttest” in which participants were provided with their baseline self-assessments when they completed the follow-up survey. Participants were then asked to assess whether their changes in knowledge were attributable to their attendance at the Leadership Academy. These open-ended questions provided a forum for participants to acknowledge their knowledge and understanding had, in fact, shifted despite having rated themselves high at baseline.

(3) Impact of Coaching and Mentoring

The added value of the coaching and mentoring components of the Leadership Academy were assessed roughly 1 year after graduation. A web-based survey assessed the quality of implementation and the ways these components resulted in continued and/or sustained changes in participants’ knowledge, behavior, and practices.

Long-Term Impact

Leadership Academy participants (N = 144) received a web-based survey in the summer of 2022 to determine the longitudinal impacts of the Leadership Academy, coaching, and mentoring. The survey contained 12 questions, including open-ended to allow participants to describe the extent to which changes that occurred in their knowledge, attitudes, and behavior in the aftermath of their participation in the Leadership Academy were sustained; and the impact these changes had on their career trajectories, personal, and professional growth.

Data Analysis

All survey items that were quantitative in nature were analyzed using inferential statistics (i.e., t tests) to determine participants’ perceived changes in their attitudes and beliefs about leadership and themselves as leaders in CLC. The quantitative data were then triangulated with rich qualitative data of participants’ views on whether their changes in knowledge were attributable to their attendance at the Leadership Academy. The evaluation team reviewed the open-ended responses, exported the data, and used thematic analysis to summarize findings. The findings, including representative quotes, were then integrated into the quantitative findings during the interpretation stage for a comprehensive insight. Similar qualitative methods were applied in the analysis of qualitative data from the coaching and mentoring surveys. Integrating and aligning these two data sources also provided insights into the specific aspects of the Leadership Academy structure and content that contributed to participants’ growth and change. Detailed results of each of the evaluation strategies are reported below.

Results

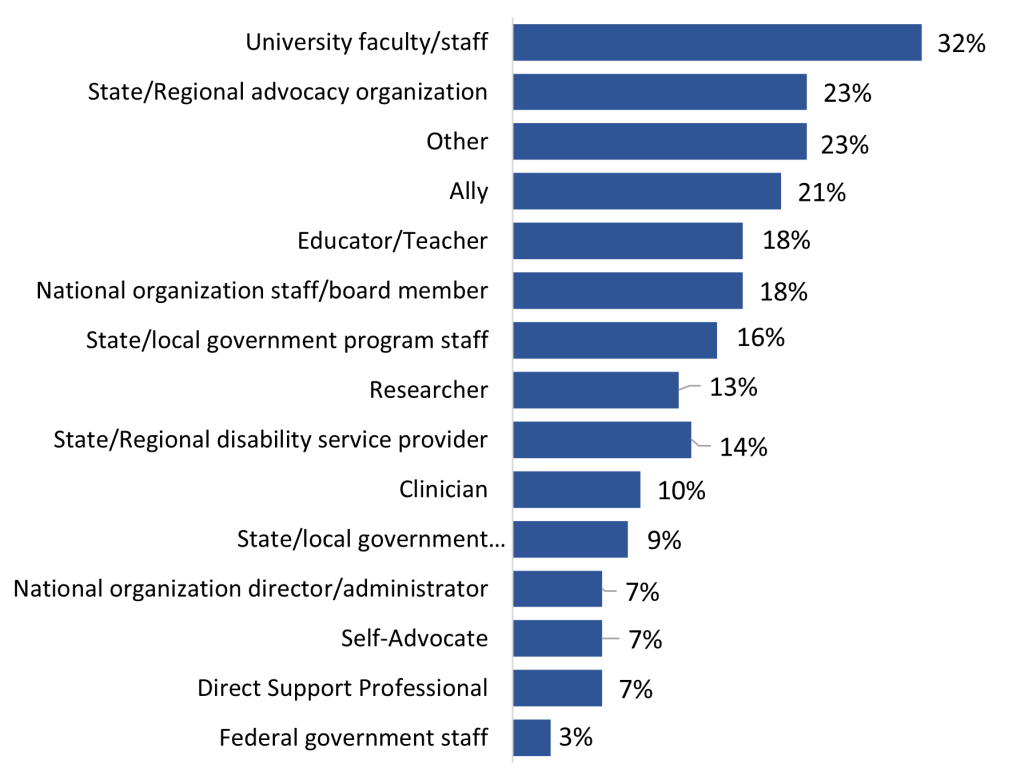

A total of 158 individuals participated in the five cohorts of the Leadership Academy. A total of 28 (18%) participants self-identified as having lived experience of disability. The participants came from a diverse network of organizations and programs concerned with IDD. Participants self-identified their roles from a broad array of options. The most commonly selected roles were university faculty/researchers (32%); state/regional advocacy and disability organizations (23%); other (23%) such as family members, parent advocates, directors, family leaders etc.; and allies (21%). Refer to Figure 1. It should be noted that while some individuals with disabilities self-identified in their applications, others did not. Participants also identified a primary area of focus for their work: just over half selected advocacy (51%), about one-third selected disability policy (33%), and family services (31%), respectively. Persons with lived experience of disability are included in these percentages.

Note. Percentages will not add up to 100% as participants could choose more than one option.

Overall, the quantitative and qualitative data from the five academies supported Leadership Academy’s theory of change, participants reported that the experience led to significant gains in knowledge and skills, changes in attitudes and beliefs, and shifts in their views of themselves as leaders. These in turn manifested in changes in practice. The data reflected participants’ increased capacity to provide leadership in challenging times and the ability to view themselves as effective, collaborative, and confident leaders for cultural diversity and CLC in networks supporting individuals with IDD.

Leading and Advancing Cultural and Linguistic Competence and Cultural Diversity

As a result of participation in the Leadership Academy: 87.2% of participants reported increased awareness and understanding of cultural competence, 74.3% stated a positive change in the way they think about advancing linguistic competence, and 84.4% indicated an increased understanding of what it means to lead or advance efforts that promote cultural diversity.

My new view of how to advance CLC is focused on leading from where I am, rather than spending energy worrying about not [having] the right position or the right title or receiving an endorsement from the right person. I have recognized that I have a lot of power in my current position, and I need to take steps in that domain first. (Cohort 5 participant)

Specific Changes in Knowledge, Skills, and Behaviors

Using paired t tests, statistically significant changes were the project’s metric for assessing the magnitude of change. In addition, the mean differences were examined to see if there was any improvement in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors post-academy. Table 4 shows the mean changes in participant scores (before and following onsite academy attendance) on their self-rated knowledge in 11 domains listed below. Across all five cohorts, there was strong evidence to suggest that participants experienced consistent statistically significantly increases (p < 0.05) in their preparedness to (a) provide leadership to mobilize change in challenging environments, (b) create a shared vision within their settings, and (c) take risks to increase cultural diversity and CLC within the broad network concerned with IDD.

I see my leadership now for what it is. I had not fully embraced my leadership, but [after] going through this experience and developing with everyone else, I find myself in a new space now where I am comfortable in my role and embrace the challenges that come with leadership. (Cohort 3 participant)

Across the majority of the cohorts, most participants experienced statistically significant increases (p < 0.05) in their abilities and skills to create spaces of trust and safety in their settings and to identify stakeholder interests. Project data also showed improvements in participants’ perception of (a) the importance of practicing self-care as leaders who deal with multiple competing demands; (b) themselves as leaders in system change efforts to increase cultural diversity and CLC in the network that support individuals with intellectual, developmental, and other disabilities; and (c) the importance of having a strong personal vision (Table 3). Other domains had little to no changes. However, as mentioned earlier, the qualitative data reinforced our concerns that some participants may have overestimated their self-assessments at the onset of their participation at the leadership academy.

| Cohort 1 (n = 29) | Cohort 2 (n = 30) | Cohort 3 (n = 35) | Cohort 4 (n = 35) | Cohort 5 (n = 29) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership Academy Domains | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p |

| Create a shared vision within your setting. | 0.714 | 0.001* | 0.893 | 0.000* | 0.567 | 0.000* | 0.806 | 0.000* | 0.815 | 0.000* |

| Provide leadership to mobilize change in a challenging environment. | 0.897 | 0.001* | 1.071 | 0.000* | 0.700 | 0.000* | 0.645 | 0.000* | 0.704 | 0.000* |

| Take risks to increase cultural diversity and CLC | 0.621 | 0.002* | 1.036 | 0.000* | 0.433 | 0.002* | 0.484 | 0.000* | 0.519 | 0.001* |

| Importance of practicing self-care as a leader | 0.069 | 0.326 | 0.536 | 0.000* | 0.533 | 0.001* | 0.452 | 0.000* | 0.630 | 0.000* |

| Skills necessary to identify stakeholder interests | 0.828 | 0.001* | 0.786 | 0.000* | 0.567 | 0.000* | 0.323 | 0.067 | 0.407 | 0.025* |

| Skills needed to create spaces of trust and safety | 0.621 | 0.002* | 0.964 | 0.000* | 0.333 | 0.096 | 0.290 | 0.037* | 0.296 | 0.133 |

| Perception as a leader in system change efforts to increase cultural diversity and CLC | 0.138 | 0.011* | 0.286 | 0.284 | 0.433 | 0.040* | 0.161 | 0.378 | 0.296 | 0.161 |

| Importance of a strong personal vision | 0.069 | 0.537 | 0.321 | 0.026* | 0.167 | 0.057 | 0.065 | 0.423 | 0.556 | 0.001* |

| Think strategically about alliances and partnerships | 0.036 | 0.832 | 0.071 | 0.626 | -0.100 | 0.557 | 0.000 | 1.000 | -0.037 | 0.846 |

| Consider how the perspectives of the cultural groups affect work as a leader | 0.250 | 0.166 | -0.107 | 0.599 | -0.233 | 0.214 | -0.226 | 0.198 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Adapt my leadership style to meet different situations | 0.069 | 0.663 | -0.286 | 0.088 | -0.233 | 0.070 | -0.419 | 0.021* | -0.037 | 0.832 |

* indicates significant p values.

Participants indicated their plans to incorporate lessons learned about cultural diversity and cultural and linguistic competence during the Leadership Academy in various facets of their work. A majority of participants planned to integrate these concepts and practices by being more intentional and thereby ensuring cultural diversity and cultural and linguistic competence are a priority in their respective organizations using new tools and knowledge gained through the Leadership Academy.

The Academy not only gave me some new tools for moving change, but also allowed me the space to process what my challenges are and how to take steps toward addressing them. I came back to work prepared to use some technical means to move to bring up what will be an adaptive issue for our Council. (Cohort 4 participant)

Follow-Up Coaching

Every participant in the academies was offered coaching to deepen their application of the new knowledge they gained during the in-person experience. Of these, 92% were able to receive at least three of the four sessions that were planned. Some unforeseen circumstances prevented participants from completing all of the scheduled coaching sessions including but not limited to family emergencies, illness, attrition/changes in work settings, and conflicting schedules. The analysis of feedback from participants revealed that coaching provided participants a crucial opportunity to deepen their understanding of the tools and techniques from the Leadership Academy and to incorporate their learning into long-term changes in their behavior. Participants reported that coaching was very beneficial as it reinforced Leadership Academy learnings, provided clarity of goals, increased self-confidence, encouraged self-reflection, and promoted relationship building.

Some of the challenges I faced in implementing change in my organization after the academy made me want to give up. Coaching helped me to stay strategic and focused and gave me fresh eyes on problems I couldn’t see my way out of. (Cohort 2 participant)

Individual Mentoring

Like coaching, mentoring allowed the gains in knowledge and skills and the shift in attitudes and beliefs to manifest in longer-term practice changes. Of the participants who received coaching, 44% opted to receive additional mentoring as a way to integrate cultural diversity and cultural and linguistic competence intentionally in their career paths and life goals. Nearly all of these participants indicated that mentoring met their expectations and 86% of those who completed the survey stated that they would recommend it. A participant shared:

The mentoring aspect gave me the tools of how to integrate cultural diversity and cultural and linguistic competence into my overall life. To clarify my point: the mentoring pushed me to think about how to include cultural diversity and cultural and linguistic competence into my research and work that might expand beyond the IDD network.

Summary of Short-Term and Interim Impacts

The Leadership Academy was successful in fostering a safe environment and supportive context for learning, as the structure enabled participants to process and reflect on their leadership abilities, challenges, and priorities. The academy strongly influenced participants as evidenced by positive changes in attitudes regarding knowledge and an awakened zeal to work both within and outside of their organizations to lead change that advances cultural and linguistic competence and cultural diversity within IDD systems nationally and internationally. This resulted in achieving the primary project goal—to increase the number and capacity of leaders to advance and sustain cultural and linguistic competence and respond to the growing cultural diversity among people with IDD in the United States, territories, and tribal communities.

Where Are They Now?

A Qualtrics survey was disseminated in 2022 to Leadership and Disparities Leadership Academies participants to ascertain whether and the extent to which they were using the training, coaching, and mentoring they received and to learn of their current leadership roles. Descriptive statistics, using SPSS, were calculated for the quantitative data and NVIVO was used to conduct a thematic analysis of the qualitative data. The Institutional Review Board of Georgetown University approved this study.

The survey was sent, via email, to 158 Leadership Academy participants and 23 Disparities Leadership participants. However, only 144 participants (n = 129 for the Leadership Academy, and n = 15 for the Disparities Leadership Academy) actually received the survey; of those, 70 completed it for a response rate of 49%. Many of the emails returned undeliverable because of job or organizational changes (Leadership Academy participants n = 21, and Disparities Academy participants n = 2), and some of the messages did not reach the participant because they had retired (participants from the Leadership Academy n = 7; participants from Disparities Leadership Academy n = 2). One of the Leadership Academy participants was deceased.

Participant Demographics

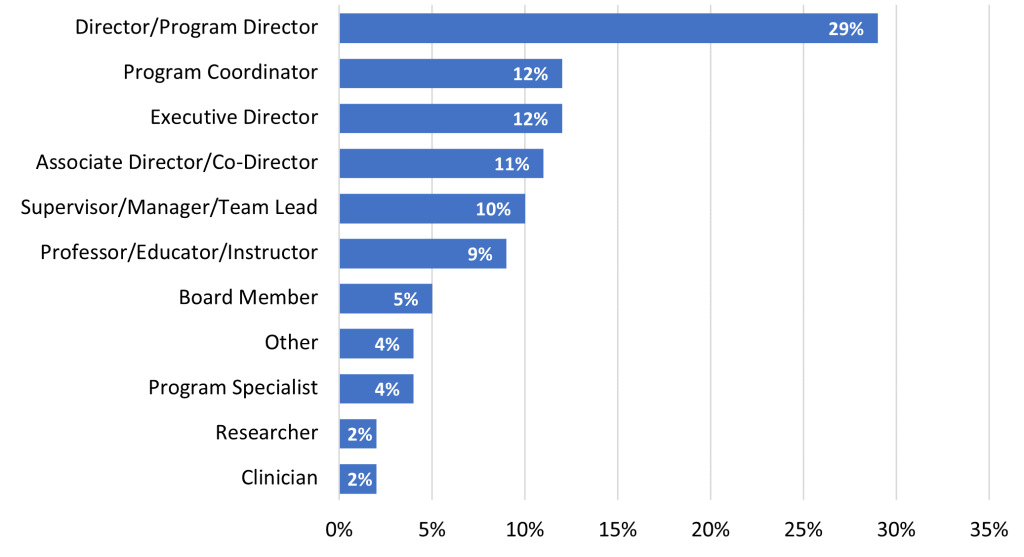

A full report of participant demographics is presented in Table 4. A majority (91.4%) of the respondents participated in the Leadership Academy, with over half of respondents who participated in optional mentoring (61.4%). Most of the respondents (74.3%) worked in the same organization where they were employed during the Leadership Academy, and 58.6% had changed positions since participating in the Leadership Academy. Of those who had changed positions, 90.2% advanced in their careers or were promoted (see Table 4). When asked to indicate their current position, most of the respondents (29%) reported that they were Directors (see Figure 2).

| Selected survey questions | N = 70 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Participated in | ||

| Leadership Academy | 64 | 91.43 |

| Disparities Leadership Academy | 5 | 7.14 |

| Participated in | ||

| Mentoring | 43 | 61.43 |

| Cohorts | ||

| Cohort 1 (2015) | 10 | 14.28 |

| Cohort 2 (2016) | 14 | 20.00 |

| Cohort 3 (2017) | 17 | 24.28 |

| Cohort 4 (Spring 2018) | 16 | 22.86 |

| Cohort 5 (Fall 2018) | 13 | 18.57 |

| Working in the same organization as during participation in Leadership Academy | ||

| Yes | 52 | 74.29 |

| No | 18 | 25.71 |

| Change in position since participation in the Leadership Academy | ||

| Yes | 41 | 58.57 |

| No | 29 | 41.43 |

| Was the change in position advancement or promotion | ||

| Yes | 37 | 90.24 |

| No | 4 | 9.76 |

Quantitative Results

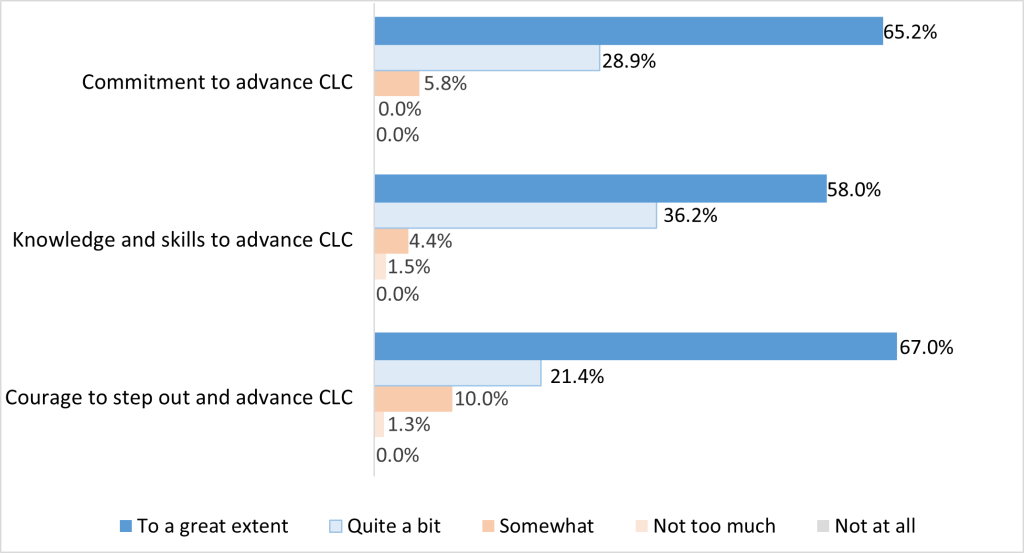

Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which their participation in the Leadership Academy enhanced their level of commitment, knowledge and skills and courage to be a force for change in the work of advancing cultural and linguistic competence (see Figure 3). The majority of the respondents stated that their participation in the Leadership Academy enhanced to a great extent their: commitment to do the work of advancing and sustaining cultural and linguistic competence in systems, organizations and programs that serve persons with IDD and their families (64%); knowledge and skills to do the work of advancing and sustaining cultural and linguistic competence in systems, organizations, and programs that serve persons with IDD and their families (57.1%); and courage to step out in the forefront of the complex set of dynamics in advancing and sustaining cultural and linguistic competence and being the force for change (67.1%).

Qualitative Results

Each of the open-ended questions was analyzed separately. The results revealed that participants, even though reporting that there are some challenges in continuing this work, had utilized the knowledge gained from the academy, and had applied what they learned to change policies, practices, and structures for advancing CLC. For each question, the themes, frequency counts and illustrative quotes from participants are detailed in Tables 5-9.

| Overarching theme | Frequency | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|---|

| Applied knowledge and skills learned into embedding CLC within an organization | 14 | “I’ve used leadership principles to create and negotiate a new State Plan that incorporates CLC throughout, to develop consensus among the DD Council for a commitment to anti-racism, and ongoing learning and action with our CLC Community of Practice.” |

| Devised new goals and pushed for organization changes to advance CLC both internally and externally | 13 | “At my new organization, we established a strategic goal around championing and modeling diversity, equity, and inclusion. We are hiring a Director of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Access, which is a new position for us, and we are developing metrics to measure how we are doing in these areas. We also adopted a new advocacy platform that centers issues faced by people with disabilities who are members of other marginalized communities.” |

| Changes in attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs | 11 | “More importantly in my experience, is that the academy allowed me to look at the barriers and self-doubt that can affect my ability to grow as a leader. I felt the academy has given me some courage to push through these self-doubts.” |

| Strengthened advocacy work | 10 | “Continue to demand change within leadership of the organization I work for. I co-chair our organizational diversity committee and now sit on a departmental DEI committee.” |

| Mentoring others using the principles learned from the Leadership Academy | 9 | “I utilized the information and training to encourage others to view diversity from a wider perspective than they may have formerly utilized.” |

| Changed and/or adapted leadership style and efforts | 7 | “Participating in the leadership academy helped me clarify my role as a leader at our Center and to be much clearer about what we were trying to accomplish. For my role, the academy helped me realize how I felt responsible for all decisions and planning, and that I needed to trust in my colleagues and our collaboration.” |

| Overarching theme | Frequency | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|---|

| Increased trainings and knowledge sharing opportunities to integrate CLC in several areas | 19 | “Every year since the Leadership Academy, I have worked to infuse cultural and linguistic competence in didactics for psychology training, LEND seminars and in all the clinical work in our program.” |

| Increased collaboration both internally and externally | 17 | “I am no longer isolated at my organization due to a combination of others attending the Leadership Academy, and new hires who came in with the relevant interests and skills. Our efforts toward health equity have evolved into a sustained, organization-wide effort that is entering its third phase with a thorough examination of all our internal values and processes.” |

| Applied changes in policies, practices, and structures in terms of advancing CLC within an organization | 14 | “Our council formally adopted a core value on diversity and equity. We revised our position on CLC to increase accountability and advance the work in all our activities.” |

| Increased community engagement, especially with underserved and underrepresented populations | 12 | “I was able to increase the number of diverse families who attended our family trainings by building relationships with community leaders.” |

| Enhanced advocacy efforts | 12 | “I continue to advocate strongly with our federal partners to increase funding for projects that will advance cultural and linguistic competence in our network. We’ve ensured every network leadership meeting and call addresses this topic.” |

| Advancements in language accessibility | 7 | “We have completed and are piloting a Language Access Plan, complete with Plain Language Workgroup and Spanish Language Caucus, and are working to expand the pilot beyond a single team to the full organization, and also share our lessons learned with the national network.” |

| Overarching theme | Frequency | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|---|

| Resistance from leadership | 17 | “It is challenging to make bold stands when you are not at the top of the hierarchy or when disrupting the status quo comes with social and professional consequences.” |

| Lack of resources in terms of time, staff, capacity, skills, funds, etc. | 12 | “Due to limited capacity and the workforce shortage, there are not enough agencies available to provide services for persons with IDD and their families.” |

| Difficulty developing a shared vision and/or lack of a shared understanding | 8 | “We have a lot of new staff and new Council members. Recently, it’s been challenging to train new staff and members on CLC and re-build organizational capacity in this area. These changes are also an opportunity to get new ideas and perspectives on how to accomplish CLC work.” |

| Lack of an intersectional view and/or analysis | 6 | “I’ve found that the many racial equity and racial justice spaces do not have an understanding of disability rights or disability justice, so it’s proven challenging to stretch and help others stretch their boundaries at the same time” |

| Slow progress | 5 | “How slow everything moves within a large organization, but just sticking with it. Motivating a committee to continue with the work when the process is slow.” |

| Not centering individuals with lived experience | 5 | “Attitudinal barriers are still the biggest challenges for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, as well as their family members. There is a lot of ableism in our culture that doesn’t see that people with disabilities, especially intellectual and developmental disabilities, deserve a seat at the leadership table. People still try to design programs and make decisions for individuals which further marginalize individuals with developmental and intellectual disabilities.” |

| Overarching theme | Frequency | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|---|

| Coaching | 31 | “Through coaching sessions, I was able to identify where I could and should attend to my own communication behaviors and how to get more comfortable with candid conversations. As a result of the coaching and my own work on myself, I became more successful in communicating with the executive director (who has since retired) and I found my leadership style of compassionate candor.” |

| Mentoring | 28 | “Mentoring was my biggest avenue of change. To be honest, I was struggling with old anger from experiencing discrimination myself. I had thoughts that if it wasn’t, me, as a Latina, no one else would make a change. I realize that I’ve made an unconscious change to ensure that everyone needs to be the change. I’m slowly evolving now.” |

| Networking | 19 | “Networking has been the most important for me – staying in contact with my fellow Leadership Academy participants helps me remember what is important and have people to process ideas with.” |

| Webinars | 15 | “…the webinars have provided me with increased knowledge and skills.” |

| Week-long training/in-person convening | 9 | “The event itself in New Mexico was a life-changing experience for me. I have come a long way since then through further teachings with the Bush Foundation, which also had a significant impact on my growth in this area.” |

| Small group discussions and interactions | 5 | “Working in our small groups was genuinely a transformative experience for me. It was a turning point in my life.” |

| Self-assessment exercises | 4 | “The self-assessments and having me to acknowledge why there were areas of service in which I was not connecting to the people I was leading” |

| Overarching theme | Frequency | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|---|

| Elevated influence and formalized role a | 17 | “The change in my leadership position to more formal roles allowed me advance cultural and linguistic competence in both technical and adaptive ways: it has allowed me to partner with other individuals in more formal and informal positions of authority to disseminate CLC based concepts, gain knowledge about resources and tools that are helpful to advance CLC, integrate concepts of CLC across various grant based training and other programs…” |

| Created new avenues and opportunities for impact | 13 | “I moved voluntarily to a new organization in large part for the opportunity to work more explicitly for equity and inclusion. At (name of organization), I have an opportunity to support leaders and teams across the organization to improve the organizational culture” |

| Able to transfer and applied knowledge into new position | 8 | “It has provided a platform to implement what I learned at the LA on a broader basis, and across all of the five projects that I am associated with.” |

Where Are They Now Survey Summary

Results of the “Where are they Now” survey revealed overwhelmingly positive reports from participants of how they are using the training, coaching, and mentoring received through the Leadership Academy to advance and sustain CLC in systems, organizations, and programs that serve persons with IDD and their families. Participants noted that their knowledge, skills, and commitment to continue these efforts were enhanced by their involvement in this leadership development initiative. Participants of the Academy reported they led changes in policy, practices, and increased advocacy. It is also encouraging to note that many of the participants that had changed jobs were either promoted or had achieved an advancement in their position or role within their respective organizations. Having leaders with the courage to facilitate change, while addressing the complex dynamics of CLC is crucial for this work to continue and is a very positive result that the Leadership Academy contributed to building participant capacity.

Limitations

There are limitations in the evaluation of all components of the Leadership Institute, and the short-term and longer-term evaluation of the Leadership Academy. First, Leadership to advance CLC and diversity in the IDD network is multidimensional, complex, and impacted by the sociocultural and political environments in states, territories, and tribal nations. Achieving CLC is a developmental process that takes place over time. NCCC faculty did not have access to required resources to conduct a long-term follow-up study of the Leadership Academy. Second, while NCCC faculty were successful in reaching Leadership Academy participants, a sizeable number were lost to attrition including retirement, leaving the IDD field, different roles and responsibilities in other organizations, and other personal matters. It is possible that two factors may have affected the moderate response rate (49%), specifically attrition and that the “Where Are They Now?” survey was conducted in the summer of 2022. Last, it should be noted that 100 participants began the survey but only 70 completed it within the designated time frame. Generalizability of the evaluation findings are limited in that the participants who responded and those who did not may differ with respect to the variables in the evaluation.

Conclusions and Implications for the IDD Network

Much of the emphasis within the IDD network has focused on training/professional development for what is and how to advance CLC, diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Very little focus has been placed on how to lead CLC and DEI. Given the sociocultural and political environments in which CLC is implemented across the U.S., territories, and tribal nations, it is obvious that leadership is an essential area of knowledge and skills within all sectors of the IDD network. There is a need for structures and resources across the IDD network to foster leadership for CLC as evidenced-based practices to advance DEI. Meeting this need will require that the network design, implement, and evaluate leadership models that are responsive to persons with the lived experience of IDD and their families, state government IDD entities, providers of supports and services, advocacy organizations, and other stakeholders. In conclusion, the NCCC’s Leadership Institute and Leadership Academies offered one multifaceted model, conducted over a five-years interval, and were able to document the benefits of a national focus on leadership across multiple stakeholders in the IDD network.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Braveman, P., Arkin, E., Orleans, T., Proctor, D., Acker, J., & Plough, A. (2018). What is health equity? Behavioral Science & Policy, 4(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1353/bsp.2018.0000

Goode, T. D. (2020). Achieving equity: Leading the way in the next decade. Association of University Centers on Disabilities. https://www.aucd.org/conference/template/page.cfm?id=50240

Goode, T. D., Jones, W., & Christopher, J. (2017). Responding to cultural and linguistic differences among people with intellectual disability. In M. L. Wehmeyer, I. Brown, M. Percy, W. L. Alan Fung, & K. A. Shogren (Eds.) A comprehensive guide to intellectual and developmental disabilities (2nd ed., pp. 389-400). Paul H. Brookes Publishing, Co.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage Publications.

Jones, C. P. (2018). Behavioral health equity. Health and Medicine Policy Research Group. https://hmprg.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Behavioral-Health-Equity-Issue-Brief_June-2018.pdf

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2019). Advancing equity in early childhood education. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/advancingequitypositionstatement.pdf

Northouse, P. G. (2001). Leadership: Theory and practice (2nd ed). Sage Publications.