5 What Do NCI Data Tell Us About the Characteristics and Outcomes of Older Adults with IDD?

Valerie J. Bradley; Dorothy Hiersteiner; Henan Li; Alexandra Bonardi; and Laura Vegas

Bradley, V. J., Hiersteiner, D., Li, H., Bonardi, A., & Vegas, L. (2020). What Do NCI Data Tell Us About the Characteristics and Outcomes of Older Adults with IDD? The Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 2(2), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.26077/ESW0-2H31

What Do NCI Data Tell Us About the Characteristics and Outcomes of Older Adults with IDD? PDF File

Plain Language Summary

We did a study of the needs of older people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) that helped us to understand ways to help them. Every year we survey adults with IDD to find out about their lives. The survey includes people from around the country. The survey gives us information about peoples’ ages and where they live. We also ask them if they have health problems. People tell us whether they have friends and if they go out and do things they like. They tell us whether they make choices and if they have a job. We ask them what they do during the day. We used what people told us in 2018 and 2019 for this study. We focused on people in the survey who were over 55 years old so we could get a picture of their particular needs. Do older people with IDD have more health issues than other older adults? Our study showed that the answer is yes. They have more trouble seeing and hearing. They have more trouble walking and getting around. They get more anxious and depressed than people without learning problems. They also show signs of old age—like forgetting things—sooner than other older people. They have fewer friends than younger people with IDD. They are less likely to have a job. They do not spend as much time doing things in their community. That may be because sometimes they cannot get a ride to get where they want to go.

How can we help older people with IDD? Here are some suggestions. There should be better planning. We should find better ways to find out about their health. We should find houses for them where they do not have to climb stairs. They should have iPads and phones so they can stay in touch with friends. Other devices can remind them to take medication. Cameras in their houses can tell us whether they are okay. Their staff should know how to help older people to stay healthy and happy. They should get rides when they want to go places.

For people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), transitions from one stage of life to another require thoughtful planning and support in order to ensure that people with IDD can continue to live a quality life according to their own preferences and needs. Whereas some of these critical life junctures have received increased attention in recent years, such as the shift from school to work, the transition when people enter their later years has received comparatively less attention. Yet, as more and more people receiving public support begin to age, it is important for policymakers, providers, and advocates to understand their unique support needs so that the transition is a success and people are able to enjoy their later years.

Using National Core Indicators (NCI)® data, this article describes the characteristics of older adults with IDD and what is known about their outcomes. We also provide suggestions for public managers, providers, and other stakeholders regarding how they might use this information to plan for and support older adults with IDD.

As discussed in this article, some older adults with IDD have health challenges in addition to those experienced by the general population. As we write this article, the global community is grappling with COVID-19, a virus that appears to affect older adults more severely than other age groups. Older adults with IDD are now facing additional challenges, both related to the virus and to the steps needed to avoid the illness (social distancing and quarantine). Though this article was written before the COVID outbreak, it offers information about the characteristics, outcomes, and health status of older adults with IDD that will prove helpful to those working to support them during difficult times.

Background

The generation born between 1946 and 1964 makes up a substantial portion of the world’s population—and nearly 20% of the American public. In the U.S., we often refer to this generation as the “Baby Boom generation,” since birth rates across the world spiked following the end of World War II. The population with IDD born during those years—5 to 7 decades ago—has lived through significant social and cultural change. In 1946, for instance, the first year of the baby boom, there were few publicly funded family and community services, and large institutions housed thousands of people with IDD. In subsequent decades, policy shifts have supported greater access to community supports, legal protections, and greater choice and control over services. In their own lives, Baby Boomers with IDD have experienced many life transitions—from early years into school through adolescence and into the many phases of adulthood. Now, as with Boomers in the general population, they are at another stage of life transition—moving into their older years.

The number of older adults in the U.S. continues to grow. Over the past 10 years, the population age 65 and over increased 38.8% from 2008 to 2018, growing from 38.8 million to 52.4 million, and it is projected to almost double to 98 million in 2060 (Administration on Community Living [ACL] and Administration on Aging [AOA], 2019). Currently, one in every seven individuals in the U.S. is over 65, and approximately one in five is over age 55.

Likewise, the numbers of people with IDD over 55 are also growing. This increase is in part the result of a growth in the average lifespan of people with IDD, which is now similar to the general population (Bittles et al., 2002; Janicki et al., 1999, as cited in Heller, 2010), with the mean age at death ranging from the mid-50s for those with more severe disabilities or Down syndrome, to the early 70s for adults with mild to moderate IDD (Minino as cited in Heller, 2010). The increase in life expectancy may be attributed to better medical care and health surveillance as well as improved living conditions. The number of adults with IDD age 60 years and older is projected to nearly double from 641,860 in 2000 to 1.2 million by 2030—when all the Baby Boom generation will be over 65 (Keller, 2019).

As people with IDD age, some will have health challenges in addition to those experienced by the general population. For instance, people with cerebral palsy may experience additional functional limitations, people with Down syndrome are more likely to experience the onset of Alzheimer’s disease at an earlier age, and people on the autism spectrum are more likely to have gastrointestinal complications. People with gait and ambulation issues may be more susceptible to falling, and osteoporosis (fragile bones) associated with aging increases the risk of serious injury from a fall (Heller, 2017).

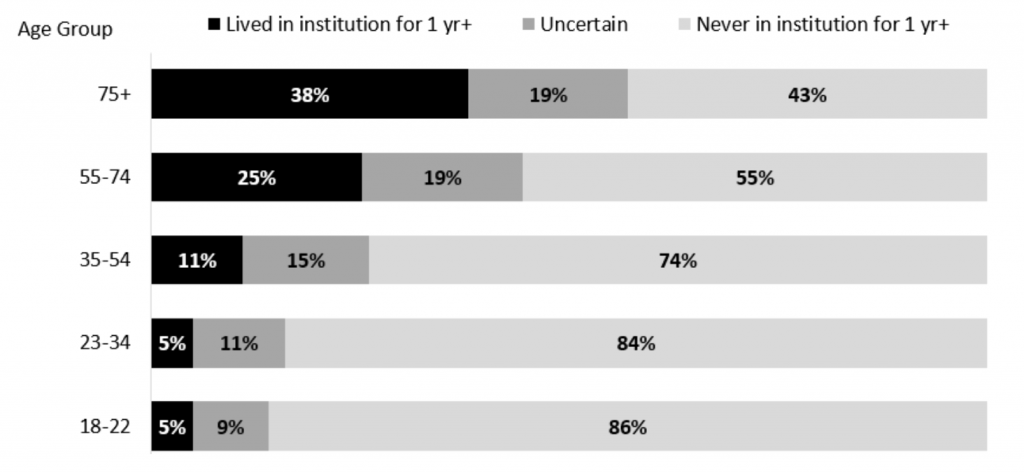

Moreover, given the shifts in models of support and care that have occurred in their lifetimes, many older adults with IDD have previously lived in an institution. Thoughtful planning for these individuals can support aging in place as a feasible option and avoid re-institutionalization in a nursing home as a person’s needs increase. As in the general population, older adults with IDD will need support for end-of-life planning and advance care directives. Like people in the general population, people with IDD need assistance to ensure they can secure adequate housing, get access to specialized health and wellness services, participate in their communities, and ensure that they are safe and secure. However, adults with IDD are at greater risk of abuse, neglect, and other violence against them than the general population. As they age and develop more functional and cognitive limitations, they may be even more vulnerable to abuse, neglect, and exploitation (Baladerian, 2010; NYC Elder Abuse Center, 2017).

According to the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and The Arc (ACL and AOA,), agencies that are organized to serve people with IDD are not necessarily equipped to provide such assistance and “have historically not planned for the challenges faced by older people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities” (ACL & AOA, n.d.) and are not prepared to address these unique needs, including providing education and training on mitigating the risk of elder abuse and neglect for a potentially more vulnerable population of older people.

Understanding how to provide services and supports to older adults with IDD requires further research and exploration. The intention of this article is to provide some insights, using NCI data from 2017-18, into the characteristics and outcomes of older adults with IDD with the hope that it will add to a growing body of knowledge.

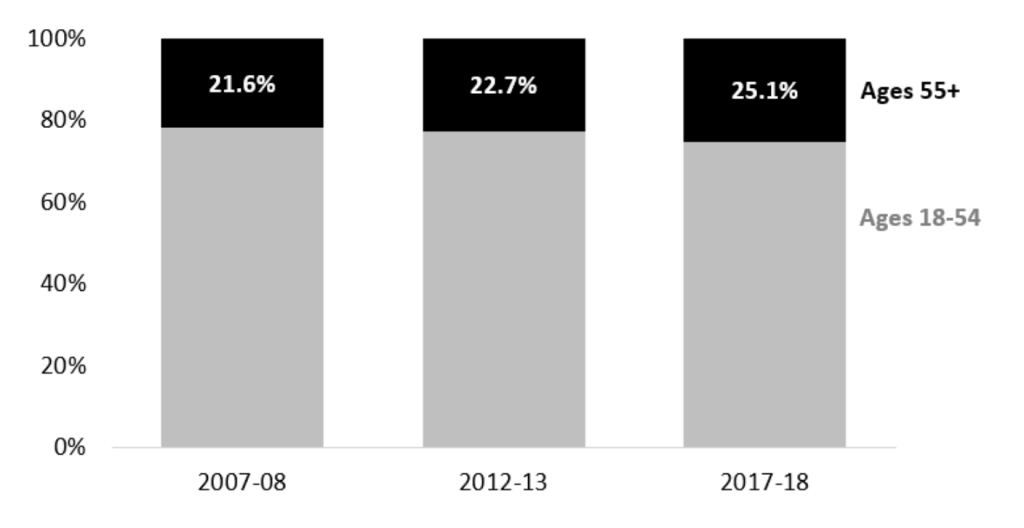

To explore the characteristics and outcomes of older adults with IDD, we analyzed NCI® In-Person Survey data that was collected in 2017-18 by 35 states and the District of Columbia. Of the 25,671 survey respondents, 25.1% were over age 55 (“older adults” for the purposes of this analysis). To determine whether the needs of older NCI respondents with IDD varies from the needs of the aging general population, we compared NCI data with results from the 2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS; U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.).

Methodology

National Core Indicators

NCI is a voluntary effort by public developmental disability agencies across the U.S. to track their own performance by examining the outcomes experienced by individuals with IDD receiving long-term services and supports (LTSS). Each year, states that participate in NCI have the option of conducting the NCI In Person Survey (IPS) with a random sample of adults with IDD receiving LTSS to gain insights into key areas of concern—including employment, rights, service planning, community inclusion, choice, health, and safety. For the purposes of reporting, the data are aggregated to produce every state’s averages and a national average. The IPS also captures information on the demographic and personal characteristics of the individuals in the sample. The NCI dataset offers a unique opportunity to examine the outcomes and personal characteristics of the population of people who receive supports from public agencies.

The data for this analysis comes from states that participated in the 2017-2018 IPS data cycle. The total sample for 2017-2018 was 25,671 individuals from 35 states and the District of Columbia. All participating states selected random samples from the population of adults (18 and over) with IDD who receive at least one publicly funded service (such as institutional, community, or home-based services) in addition to case management. There are no a priori pre-screening or exclusion procedures. States are required to interview a sample large enough so that it meets power requirements of 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error.

The NCI IPS is composed of three parts. The first part is the Background Information Section, which is used to collect demographic and personal characteristics of the individual being surveyed; this information is usually drawn from individual, agency, or case management records. In this section, the respondents’ ages are collected. Historically, the second and third parts of the Survey have been collected via an in-person interview only. (NCI states are now piloting remote surveying techniques in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.) The second part of the survey contains questions on the individual’s personal subjective opinions; it can only be answered by the individual personally receiving services. The third part of the survey contains questions that pertain to more directly observable, measurable occurrences, such as how often the person participates in specific community events; consequently, proxy responses (e.g., from family members, staff, etc.) are permitted for this portion.

The NCI IPS includes domains aligned with quality-of-life outcomes like those described by Schalock et al. (2002). This framework allows state public managers to assess the performance of public IDD LTSS systems in terms of the life outcomes of those served. This exploratory analysis uses NCI data to assess the characteristics, needs, and outcomes of older adults in the national sample. Of the 25,671 survey respondents, 25.1% were over age 55 (“older adults” for the purposes of this analysis).

Data included in the ensuing discussion are limited to those items that demonstrated significant differences between the different age cohorts. We include only those data that show a significance level of p ≤ .000. Also included are elements for which the lack of significance was unexpected and were, in the authors’ judgement, relevant to policy and practice concerns.

For this analysis, we divided the survey sample into four cohorts (as shown in Table 1).

| Age | Frequency | Percent of sample |

|---|---|---|

| Under 55 | 19,149 | 74.9 |

| 55-64 | 4,065 | 15.9 |

| 65-74 | 1,826 | 7.1 |

| 75+ | 522 | 2.0 |

| Total | 25,562 | 100.0 |

National Health Interview Survey

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)—which dates to 1957—is an annual, in-person survey administered by the U.S. Census Bureau. The NHIS is the largest in-person household health survey and is the primary source of information on the health of the civilian non-institutionalized population. Questions on NHIS include the presence of chronic conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes; sensory impairments; dental health; use of prescription medication; mental health and cognitive issues; immunization history; and availability of health insurance. The survey also includes demographic data including household size, income, race, and ethnicity.

During the 2019 survey, the sample size was approximately 35,000 households containing about 87,500 persons (National Center for Health Statistics, 2019). The NHIS is a cross-sectional household interview survey. Sampling and interviewing are continuous throughout each year. The sampling plan follows an area probability design that permits the representative sampling of households and noninstitutional group quarters (e.g., college dormitories). Clusters of addresses are defined within each state. Each cluster is located entirely within a county, a small group of contiguous counties, or a metropolitan statistical area. The current sampling plan is a sample of these clusters of addresses. Survey participation is voluntary and confidential. The annual response rate is approximately 70%.

The total NHIS sample is subdivided into four separate panels, or sub designs. The result is that each panel is a representative sample of the U.S. population. This design feature has several advantages, including flexibility for the total sample size. Data are collected by interviewers employed and trained by the U.S. Census Bureau. For the Family Care component, all adult members in the household over 17 are invited to respond. For children and adults not at home, information can be provided by a responsible adult.

Comparisons

For all NHIS data, we have included the confidence interval (CI) in parentheses next to the relevant percentage. If the NCI data falls outside of this interval, it means the NCI data are statistically significantly different from the NHIS data. In this analysis, most of the NCI data are statistically significantly different from the NHIS data.

However, when NCI data show a statistically significant over- or underrepresentation when compared to the general public, differences in NCI sampling versus NHIS sampling should be considered. For example, NCI data are collected from adults receiving at least one service in addition to case management from the state system of developmental disabilities (DD) supports. Some states limit their samples to certain programs or waivers, while some states include the entire population of adults receiving DD services (for more see 2017-18 In-Person Survey PART II: History, Methodology, Appendices).

Trends

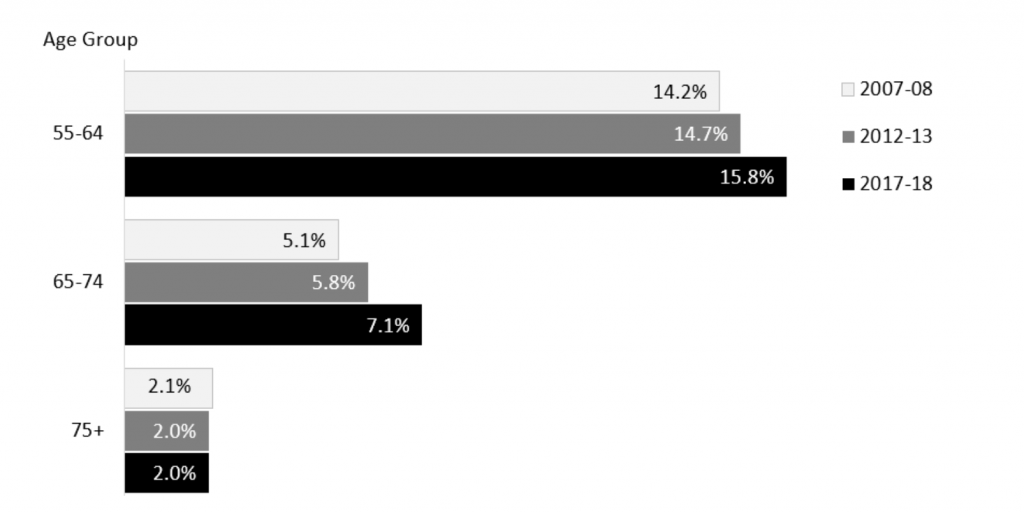

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the population of older adults in the NCI sample grew during the last 10 years of NCI data collection.

Graphic Depicting Proportion of People Over Age 55 in the NCI Sample

Graphic Depicting Proportion of NCI Sample in Different Age Groups, By Year

Caregivers are also aging—64% of caregivers who responded to the 2018-19 NCI Adult Family Survey were between the ages of 55 and 74, and 11% were 75 years and over. In two states, 13% of the respondents were caregivers over 75.

Given the shifts in models of support and care that have occurred in their lifetimes, many older adults with IDD have previously lived in an institution. As shown in Figure 3, based on NCI In-Person Survey data from the 2017-2018 data cycle, 38% of people over age 75 who were living in the community had previously lived in an institution, as had 25% of those who were between the ages of 55 and 75.

Graphic Depicting Proportion of People in Different Age Groups Reported to Have Lived in an Institution for One Year or More

Demographics

Age

Older adults with IDD (those over 55) represent only 25% of the NCI population. The national portion of the general population over age 55 is 37.4%. In Table 2, you can see that the NCI data points fall outside the NHIS 95% CI. This means the NCI data are statistically significantly different from the NHIS data. Those over age 55 may be underrepresented in the NCI dataset when compared with the general population.

| Age | NHIS (%) | NHIS 95% CI (%) | NCI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 55 | 62.6 | 61.9-63.3 | 74.9 |

| 55-64 | 16.9 | 16.5-17.3 | 15.9 |

| 65-74 | 12.2 | 16.5-17.3 | 7.1 |

| 75+ | 8.3 | 8.0-8.6 | 2.0 |

Race

As shown in Table 3, older adults (55+) in the NCI data are more likely to be non-Hispanic Whites when compared to the comparable age group in the general public. The proportion of non-Hispanic Black respondents in the older age groups in the NCI sample roughly approximates the proportion in the NHIS sample. (Notably though, non-Hispanic Black respondents are overrepresented in the younger age groups in the NCI data.) Table 4 shows that Hispanic respondents to NCI are significantly underrepresented in the older cohort when compared to the NHIS data.

| White NHIS | Black NHIS | All other race groups NHIS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | % | CI (%) | White NCI (%) | % | CI (%) | Black NCI (%) | % | CI (%) | All other race groups NCI | NHIS (N) | NCI (N) |

| Under 55 | 57.8 | 56.1-59.5 | 63.9 | 13.5 | 12.5-14.5 | 17.4 | 8.6 | 7.8-9.4 | 6.5 | 32,124 | 18,920 |

| 55-64 | 70.6 | 68.7-72.4 | 75.7 | 11.7 | 10.6-12.9 | 15.7 | 6.0 | 5.2-6.9 | 3.0 | 9,950 | 4,045 |

| 65-74 | 75.0 | 73.1-76.8 | 82.6 | 9.8 | 8.8-10.9 | 11.1 | 6.1 | 5.3-7.1 | 3.2 | 7,820 | 1,811 |

| 75+ | 79.1 | 77.1-80.9 | 86.6 | 8.4 | 7.3-9.6 | 8.2 | 4.8 | 3.9-5.7 | 2.4 | 5,092 | 520 |

| Hispanic NHIS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | % | CI | Hispanic NCI (%) | NHIS (n) | NCI (n) |

| Under 55 | 20.1 | 18.7-21.6 | 12.2 | 32,124 | 18,920 |

| 55-64 | 11.6 | 10.4-13.0 | 5.6 | 9,950 | 4,045 |

| 65-74 | 9.1 | 7.9-10.4 | 3.1 | 7,820 | 1,811 |

| 75+ | 7.8 | 6.6-9.1 | 2.8 | 5,092 | 520 |

Gender

The majority of the NHIS sample, as shown in Table 5, is female in all age groups. In the NCI data, the majority of younger cohorts are male. However, the majority of the 75+ age group is female.

| Male NHIS | Female NHIS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | % | CI | Male CI (%) | % | CI | Female NCI (%) | NHIS (n) | NCI (n) |

| Under 55 | 49.4 | 49.0-49.9 | 60.2 | 50.6 | 50.1-51.0 | 39.8 | 32,124 | 19,104 |

| 55-64 | 48.3 | 47.5-49.1 | 55.3 | 51.7 | 50.9-52.5 | 44.7 | 9,950 | 4,056 |

| 65-74 | 46.9 | 46.0-47.7 | 51.0 | 53.1 | 52.3-54.0 | 49.0 | 7,820 | 1,822 |

| 75+ | 41.8 | 40.6-43.0 | 48.9 | 58.2 | 57.0-59.4 | 51.1 | 5,092 | 522 |

General Health Status

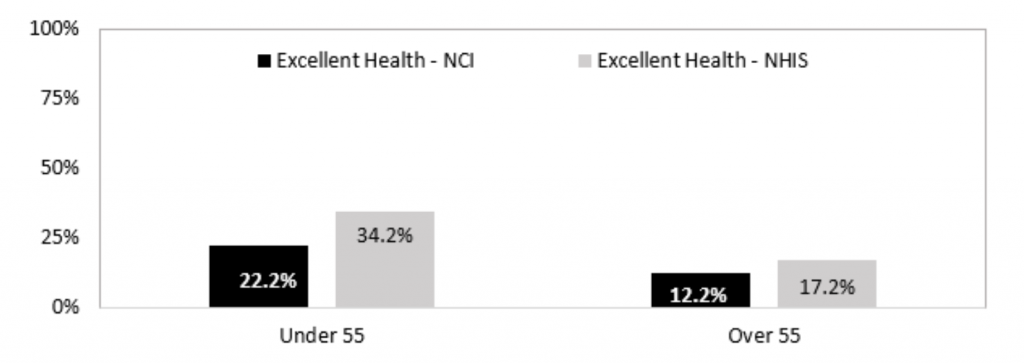

In NCI, those under age 55 are more likely to self-report excellent health (see Figure 4). However, when compared to the general population, those in the NCI sample both under and over 55 are less likely to report excellent health. NHIS = National Health Interview Survey

Excellent Health Status by NCI Age Group

Co-Occurring Conditions

The older age cohorts in the NCI data are significantly more likely to be reported as being diagnosed with mood and anxiety disorders. As may be expected, the proportions of the sample who are reported to have limited or no vision or hearing loss (severe or profound) goes up as age increases.

Comparisons to the NHIS sample should be made with caution, since the questions are not identical. NHIS asks about whether the person is “Limited in any way in any activities because of physical, mental or emotional problems.” If the answer is yes, the NHIS asks what causes the limitation. To make the data comparable to the NCI data, we included people who reported to be and those reported not to be limited in any way in any activities because of physical, mental, or emotional problems in the denominator when calculating the NHIS percentages.

As shown in Table 6, when compared to the general public, mood, anxiety, psychotic, or other mental health diagnoses are overrepresented in the NCI sample in all age cohorts. Similarly, vision problems and hearing problems, as shown in Table 7, are also overrepresented in the NCI sample.

| NHIS: Depression/anxiety/emotional problem causes limitation (N = 9,273) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | % | CI | NCI: Mood, anxiety, or behavior diagnosis (%) (N = 24,637) |

| Under 55 | 26.2 | 24.3-28.2 | 42.7 |

| 55-64 | 15.1 | 13.3-17.1 | 50.7 |

| 65-74 | 9.1 | 7.6-10.7 | 48.7 |

| 75+ | 4.5 | 3.6-5.5 | 45.2 |

| NHIS vision problema (N = 9,273) | NHIS hearing problemc (N = 9,273) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | % | CI | NCI vision problemb (N = 24,300) | % | CI | NCI hearing problemd (N = 24,113) |

| Under 55 | 7.2 | 6.1-8.5 | 8.8 | 2.9 | 2.3-3.7 | 4.9 |

| 55-64 | 8.3 | 6.9-9.9 | 11.2 | 3.6 | 2.9-4.6 | 7.6 |

| 65-74 | 7.6 | 6.4-9.0 | 13.6 | 4.8 | 3.9-6.1 | 11.0 |

| 75+ | 9.5 | 8.3-11.0 | 15.0 | 10.2 | 8.7-11.8 | 18.1 |

b “Diagnosis of limited or no vision.”

c “Hearing problem causes limitation.”

d “Diagnosis of hearing loss, severe or profound.”

NCI Data (Without Comparisons to General Public)

There were several relevant NCI measures that did not have comparable data points within the NHIS data. These data points are presented in this section.

Other Disabilities

The cohort under age 55 is much more likely to be reported to have a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder and similarly more likely to have a diagnosis of cerebral palsy when compared with the older cohorts. Table 8 shows that the proportion of the sample reported to have Down syndrome goes down as age goes up, which is not surprising given early onset Alzheimer’s in this group of participants and a shorter life expectancy.

| Age | Autism spectrum disorder (%) (N = 24,663) | Cerebral palsy (%) (N = 24,790) | Down syndrome (%) (N = 22,562) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 55 | 25.6 | 16.6 | 9.7 |

| 55-64 | 7.6 | 12.2 | 7.4 |

| 65-74 | 4.4 | 12.7 | 2.5 |

| 75+ | 2.3 | 13.4 | 1.1 |

Other Conditions

In the NCI sample, as shown in Table 9, the incidence of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol increases as age increases. The incidence of Alzheimer’s or other dementia also increases–19% of people over age 75 (nearly 1 in 5) are reported to have Alzheimer’s disease or another dementia.

| Age | Cardiovascular disease (%) (N = 24,302) | Diabetes (%) (N = 24,464) | Cancer (%) (N = 24,553) | High blood pressure (%) (N = 24,204) | High cholesterol (%) (N = 23,610) | Alzheimer’s or other dementia (%) (N = 24,453) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 55 | 5.4 | 8.5 | 1.3 | 14.8 | 13.1 | 1.1 |

| 55-64 | 11.3 | 18.3 | 4.3 | 37.6 | 35.7 | 6.4 |

| 65-74 | 17.2 | 21.2 | 6.1 | 44.9 | 39.4 | 8.5 |

| 75+ | 24.8 | 23.6 | 12.5 | 49.7 | 44.6 | 19.0 |

Preventive Health Screenings

Perhaps not surprisingly, the NCI data, included in Table 10, indicate that proportions of respondents who received vision exams, hearing tests, flu vaccines, and/or mammograms in the past year increase as age increases.

| Age | Vision exam in the past year (%) (N = 20,889) | Hearing test in past year (%) (N = 16,520) | Flu vaccine in past year (%) (N = 19,902) | Women age 40+ mammogram in past year (%) (N = 4,120) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 55 | 54.4 | 52.2 | 68.8 | 68.5 |

| 55-64 | 66.7 | 65.9 | 85.6 | 81.8 |

| 65-74 | 68.4 | 67.6 | 90.3 | 72.1 |

| 75+ | 71.2 | 75.6 | 92.3 | 60.7 |

Where People Who Are Aging Live

Tables 11 and 12 describe the places where older adults in the NCI sample live and have lived. Those over age 55 are significantly more likely to live in an Intermediate Care Facility for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (ICF/IID), nursing facility, or other institutional setting than those under age 55. Older individuals are also significantly more likely to live in a group residential setting as opposed to an individual setting. Those over 55 are significantly less likely than the younger cohort to live with family or parents. As stated previously, in their lifetimes, those in the NCI sample who are over 55 are significantly more likely to have lived in a state hospital or state developmental center for people with IDD, a private ICF, and/or a nursing home for longer than a year than those under age 55.

| Age | ICF/IID, nursing facility or other institutional setting (%) | Group residential setting (e.g., group home) (%) | Own home or apartment (%) | Parents/ relatives home (%) | Foster care or host home (%) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 55 | 3.7 | 25.7 | 16.7 | 50.0 | 3.8 | 18,684 |

| 55-64 | 10.6 | 45.0 | 24.9 | 13.9 | 5.7 | 3,955 |

| 65-74 | 10.6 | 53.5 | 22.7 | 7.8 | 5.5 | 1,764 |

| 75+ | 13.7 | 56.5 | 17.1 | 5.0 | 7.7 | 504 |

| Total | 5.5 | 31.5 | 18.5 | 40.2 | 4.3 | 24,907 |

| Age | Longer than a year in state hospital or state developmental center for people with IDD (%) | Longer than a year in a private ICF (%) | Longer than a year in a nursing home (%) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 55 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 18,979 |

| 55-64 | 14.0 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 4,023 |

| 65-74 | 20.0 | 6.0 | 3.7 | 1,805 |

| 75+ | 25.0 | 10.0 | 4.3 | 520 |

Medication

Table 13 indicates that respondents over the age of 55 are significantly more likely to take medications for mood or anxiety disorder. Respondents over the age of 55 are significantly less likely to take meds for behavior challenges.

| Takes meds for mood, anxiety, psychotic | Takes meds for behavior challenges | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | % | n | % | n |

| Under 55 | 45.0 | 12,314 | 21.2 | 12,310 |

| 55+ | 55.3 | 4,120 | 16.5 | 4,098 |

Mobility Impairments

In the NCI sample, Table 14 shows that among older adults the need for mobility assistance increases as age increases.

| Age | Moves self around environment without aids (%) | Moves self around environment with aids or uses wheelchair independently (%) | Nonambulatory, always needs assistance (%) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 55 | 81.3 | 10.3 | 8.4 | 19,004 |

| 55-64 | 72.1 | 19.0 | 8.9 | 4,034 |

| 65-74 | 60.1 | 27.8 | 12.0 | 1,804 |

| 75+ | 42.4 | 42.6 | 15.1 | 515 |

What People Do During the Day

Based on the data in Table 15, as age increases, people in the NCI sample are less likely to have either a paid community individual or group job or a job in a community business that primarily hires people with disabilities. Participation in an unpaid community activity also goes down as age goes up, while participation in paid and unpaid facility-based activities goes up but decreases again after age 75.

| Age | Paid community joba (%) | Unpaid community activity (%) | Paid facility-based activity (%) | Unpaid facility-based activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 55 | 18.2 | 21.2 | 13.8 | 35.6 |

| 55-64 | 11.4 | 20.9 | 17.6 | 46.2 |

| 65-74 | 6.2 | 18.4 | 14.7 | 50.7 |

| 75+ | 1.5 | 15.1 | 8.0 | 49.3 |

Transportation

There is no statistical significance in the differences between the percentages of people in each age cohort who reported almost always being able to get where they need to go. However, Table 16 shows that the percentage of those who report that they are almost always able to get places when they want to do something outside of the home—like going to see friends or going to do something fun—declines as age increases.

| Age | Almost always able to get places to do something enjoyablea (%) | n |

|---|---|---|

| Under 55 | 84.5 | 12,698 |

| 55-64 | 81.4 | 2,661 |

| 65-74 | 81.0 | 1,198 |

| 75+ | 79.0 | 333 |

Relationships

According to the data in Table 17, as age goes up, older NCI respondents are less likely to have friends who are not family or staff.

| Age | Has friends who are not staff or family (%) | n |

|---|---|---|

| Under 55 | 78.8 | 12,787 |

| 55-64 | 75.6 | 2,680 |

| 65-74 | 71.8 | 1,211 |

| 75+ | 70.9 | 340 |

Community Inclusion

Table 18 shows that those over age 55 were less likely to have gone into the community for shopping, for entertainment, to go out to eat, or to attend a religious or spiritual practice/service at least once in the past month.

| Shopping | Entertainment | Out to eat | Out to religious or spiritual practice | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n |

| Under 55 | 90.1 | 18,600 | 75.2 | 18,598 | 86.9 | 18,624 | 41.1 | 18,432 |

| 55+ | 87.2 | 6,210 | 70.5 | 6,215 | 84.4 | 6,221 | 38.3 | 6,175 |

Discussion

What we have learned about people with IDD who are aging—both based on the NCI data and existing research—has implications for the design of policy and programs targeted to older adults with IDD. Specifically, these findings point to the fact that older adults with IDD are more isolated, have smaller social networks than their younger peers, and have less access to transportation to get where they want to go. One important way to address this isolation is to facilitate access to community programs geared to older adults in the general population—including senior centers and other resources geared to socialization, nutrition, wellness, housing, and benefits counseling. Yet, efforts to bridge the gap between systems that serve older adults and those that serve people with IDD have been minimal despite federal efforts beginning in the 1980s and 1990s to incentivize such collaboration, including legislative changes, federal grants, and the development of memoranda of understanding (MOU) at the federal and state level between developmental disabilities and aging agencies. According to Factor et al. (2012), these efforts were undermined over time by changing leadership and changing federal and Congressional priorities. Renewed efforts between aging and IDD agencies will be required to bring about a sustainable partnership to make individuals with IDD welcome in generic aging programs.

Many older adults with IDD experience changes in their physical and cognitive abilities. The NCI data show that those over 55 are more likely to have vision and hearing challenges than the general public and have a greater need for mobility supports. In addition, our data demonstrate that older adults in the NCI sample are more likely than the general population to have a mood and/or anxiety disorder. To tailor supports to meet these challenges, assessment protocols geared to older individuals will be important. Further, these findings point to a need to design services and supports that accommodate age-related limitations and to help people adjust to sensory, psychological, and mobility changes.

Given these changes, older adults with IDD can also benefit from a range of technological advances including but not limited to remote monitoring, communication devices, GPS trackers, medication organizers and dispensers with timers or enabled with remote monitoring, security systems, home sensors, and voice-activated assistants. To ensure that individuals can receive technological support through HCBS waivers, person-centered service plans should include goal(s) linked to the need for a specific device and the steps necessary to ensure that the individual is able to use it. Low-interest loans may also be available from federally funded assistive technology centers.

The data demonstrate that those over age 55 are significantly less likely to work in a paid community job and are more likely to be involved in unpaid, facility-based activities. For those in unpaid facility-based activities, person-centered approaches would dictate that we ask them whether they want to remain there, want to retire, or want to participate in more community-oriented activities. Further, for those who do not have a job, the data suggest that many older adults would like a job—23% of those between ages 55-64, 12.9% of those between ages 65-74, and 12.9% of those over 75. Plans for these individuals should include employment goals.

Dementia in later years is also an issue for people with IDD, especially for individuals with Down syndrome for whom the onset of Alzheimer’s starts 20 years earlier than for the general population (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2003). Jokinen et al. (2013) in Guidelines for Structuring Community Care and Supports for People with Intellectual Disabilities Affected by Dementia note that the first step in treating Alzheimer’s is to maintain the individual’s quality of life. The authors recommend shared initiatives “across agencies and organizations that involve the aging, disability, and dementia care systems, whether for family supports, day respite, residential, or other supports and services” (p. 40).

The increase in mobility issues noted above may necessitate home modifications or relocation to more accessible housing. As part of person-centered planning, support coordinators should anticipate mobility challenges and explore the availability of federally funded low-income rent supplements for older adults as well as housing available through the HUD Section 202 program.

Direct support professionals (DSPs) play an important role in supporting individuals to make the transitions that older adults with IDD face. According to Sedlezky (2013), DSPs need to be knowledgeable about the following five aging-related areas: (1) awareness of physical and mental health changes, (2) supporting aging in place, (3) retirement and later-life social networking, (4) grieving and loss, and (5) end-of-life planning.

Finally, though racial and ethnic disparities among older adults with IDD were not explored in this analysis, further research is needed into racial and ethnic disparities that may appear or become exacerbated as the population of adults with IDD ages. The differential impact that COVID-19 has had on minorities and low-income communities has provided adequate evidence of serious health disparities in the general population. It will be important to explore whether these disparities occur among older adults with IDD receiving public long-term services and supports.

Limitations

The analyses presented in this paper are from a dataset collected from the NCI. The sample includes a random sample of people who are receiving services from state systems responsible for people with IDD and, therefore, does not include people with IDD who do not receive public services. Consequently, any conclusions cannot be extrapolated to the larger population of older adults with IDD. In addition, states participating in NCI may create slightly differing sampling frames. Further, the findings are not adjusted for differences in demographic characteristics between the different age cohorts within the NCI sample.

Comparisons between NCI and NHIS data should be approached with some caution given differences in survey administration and methodology. For example, the sampling methodology for NCI and NHIS differ, so the populations may differ by more than just the receipt of state IDD services. In addition, many questions are worded differently across surveys. Despite these factors, the differences between characteristics of older adults with IDD and the general population identified in this study highlight potential topics for further examination.

Conclusions

State IDD systems should be prepared to examine their policies, programs, and practices to ensure they can adequately support older adults with IDD and their families as they age. The needs of older adults with IDD should be anticipated and planned for in advance. This requires shifting to planning formats that take into consideration the supports needed across the lifespan. One successful approach to such planning is being employed by The Community of Practice (COP) for Supporting Families of Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, which is working with six states to develop systems of support for families throughout the lifespan of their family member (http://supportstofamilies.org/). The COP is supported by the National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services, the University of Missouri Kansas City-Institute on Human Development (UMKC-IHD), and the Human Services Research Institute (HSRI). The COP website includes valuable resources regarding the application of Charting the LifeCourse tools: http://www.lifecoursetools.com/planning/.

References

Administration on Community Living and Administration on Aging. (2019). 2019 profile of older Americans. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2019ProfileOlderAmericans508.pdf

Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2003). Dementia and intellectual disabilities: Why the concern about dementia among people with intellectual disabilities? https://www.alz.co.uk/adi/pdf/intellectualdisabilities.pdf

American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and The Arc. (n.d.). Joint position statement on aging. https://www.aaidd.org/news-policy/policy/position-statements/aging

Bittles, A., Petterson, B., Sullivan, S., Hussain, R., Glasson, E., & Montgomery, P. (2002). The influence of intellectual disability on life expectancy. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Science and Medical Science, 57, 470-472.

Baladerian, N. J. (2010). Elder abuse programs and elders with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Impact, 23(1), 30. University of Minnesota, Institute on Community Integration. https://ici.umn.edu/products/impact/231/231.pdf

Factor, A., Heller, T., & Janicki, M. (2012). Bridging the aging and developmental disabilities service networks: Challenges and best practices. University of Illinois at Chicago, Department of Disability and Human Development. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/aidd/bridgingreport_3_15_2012.pdf

Heller, T. (2010). People with intellectual and developmental disabilities growing old: An overview. Impact, 23(1), 2-3. https://ici.umn.edu/products/impact/231/231.pdf

Heller, T. (2017). Service and support needs of adults aging with intellectual/developmental disabilities: Testimony to the U.S. Senate Committee on Aging. https://www.aging.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/SCA_Heller_10_25_17.pdf

Janicki, M. P., Dalton, A. J., Henderson, C., & Davidson, P. (1999). Mortality and morbidity among older adults with intellectual disability: Health services considerations. Disability and Rehabilitation, 21(5/6), 284–294.

Jokinen, N., Janicki, M. P., Keller, S. M., McCallion, P., Force, L.T., & the National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices. (2013). Guidelines for structuring community care and supports for people with intellectual disabilities affected by dementia. National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices & Center for Excellence in Aging & Community Wellness. https://aadmd.org/sites/default/files/NTG-communitycareguidelines-Final.pdf

Keller, S. (2019). Aging in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Concerns and hope. https://www.dsamidlands.org/file_download/15567524-74e4-4654-951f-435f77c9fbe4

National Center for Health Statistics. (2019). About the Health Interview Survey. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm#:~:text=With%20four%20sample%20panels%20and,households%20containing%20about%2087%2C500%20persons.

NYC Elder Abuse Center. (2017). Elder abuse and older adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. https://nyceac.org/elder-abuse-older-adults-intellectual-developmental-disabilities/

Sedlezky, L., Reinke, J., Larson, S. & Hewitt, A. (2013). National frontline supervisor competencies. Research & Training Center on Community Living Institute on Community Integration, University of Minnesota. https://rtc.umn.edu/docs/National_Frontline_Supervisor_comp_7-2-13.pdf.

Schalock, R., Brown, I., Brown, R., Cummins, R., Felce, D., Matikka, L., Keith, K., & Parmenter, T. (2002). Conceptualization, measurement, and application of quality of life for persons with intellectual disabilities: Report of an international panel of experts. Mental Retardation, 40(6), 457-470.

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). National Health Interview Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/nhis.html