Rhythm and Meter: Examples

Julianne Larson and Tanner Doyle

“Great God Almighty,” arranged by Stacey V Gibbs, contains a clear example of syncopation against a well-established beat. The first three beats of this main melody are articulated by accented syllables (GREAT GOD alMIGHTy). The second “great,” then, is syncopated just before the downbeat of measure 11, and the following “God” just before beat 2. This gives the refrain a less “square” feel and keeps it driving forward with energy. Which words of this refrain would a conductor most likely want to emphasize? Gibbs puts accents on both “great” and “God” in measure 11, indicating he wants them to jump out at the audience. What are some ways a conductor could ensure those words are emphasized properly?

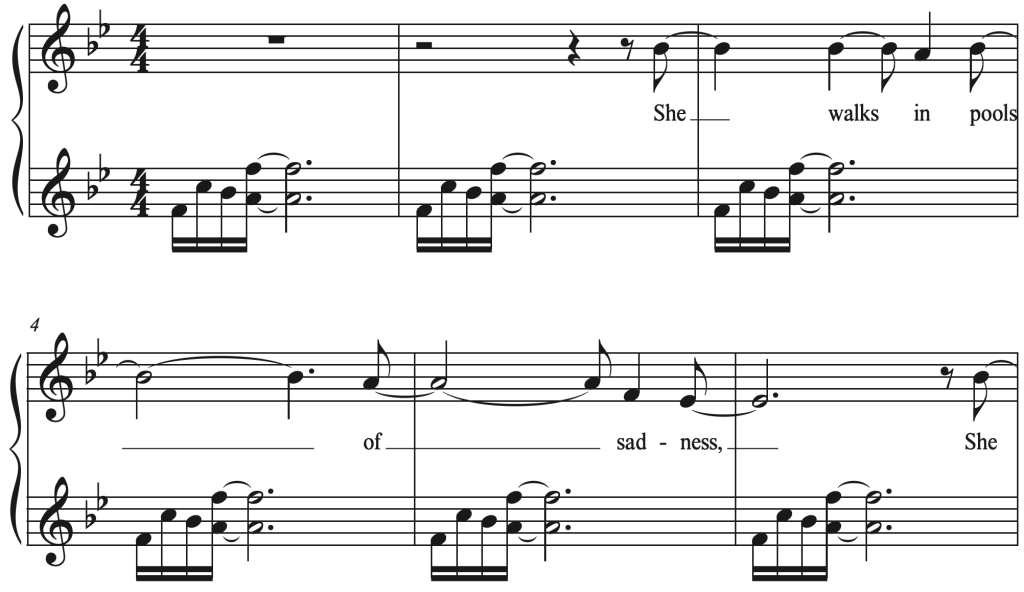

“She Lingers On” by Zanaida Robles offers an example of syncopation where the beat is not so clear. The voices often enter on the ends of weaker beats, making it difficult to feel the pulse. The piano’s ostinato at the beginning of each measure in the introduction offers a more stable event for our ears to hold onto when searching for the meter, but it is held out for so long that when each voice enters the audience may not recognize the off-beat at all. The performers of this piece will have a very different understanding of the rhythm and meter than the audience will. With the lack of a strong pulse, this piece feels more floaty and free-form, unlike our previous syncopation example, “Great God Almighty”. This means our singers will be working hard to accurately perform the syncopation, but the audience may not hear it as being off the beat at all.

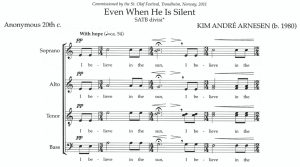

Kim Andre Arnesen’s “Even When He Is Silent” uses fermatas to create a section that doesn’t aurally abide by the written meter. Throughout the intro, each phrase is punctuated with a fermata. This creates a moment of quiet between each line, and this moment can last as long as the conductor wishes. This makes the whole introduction feel like it exists outside of the written meter. As a result, the piece feels still and contemplative, much like a prayer. The choice to include so much silence in the opening is an effective way to convey the meaning of the text. One could interpret the moments of quiet as the moment right after a prayer, when it has yet to be answered.

“The Embers Tell” by Mattea Williams contains an example of polymeter. It is difficult to aurally identify the meter of the section of the piece shown below because of the conflict between voice parts. The 123 123 12 in the upper three voices works against the 12345 12345 in the Alto 2 line. This almost forces the ear to focus on one pattern at a time, and the alto section falls into the background, a sort of constant undercurrent of sound under the more prolonged pattern. This piece is meant to imitate the sound and movement of a campfire, so these conflicting patterns can be seen as the chaotic and independent flames that make up a fire.

Rhythm and meter are vital tools composers use to craft the story of their pieces. When we see something rhythmically that subverts our expectations, we must ask why the composer chose to emphasize that moment. As analysts and choral directors, identifying important rhythmic moments and interpreting what they mean not only helps us understand the piece better, but allows us to make better informed conducting choices.