Harmony: Examples

Allison Johnston and Sierra Wamsley

Example 1: Importance of key in “Earth Song”

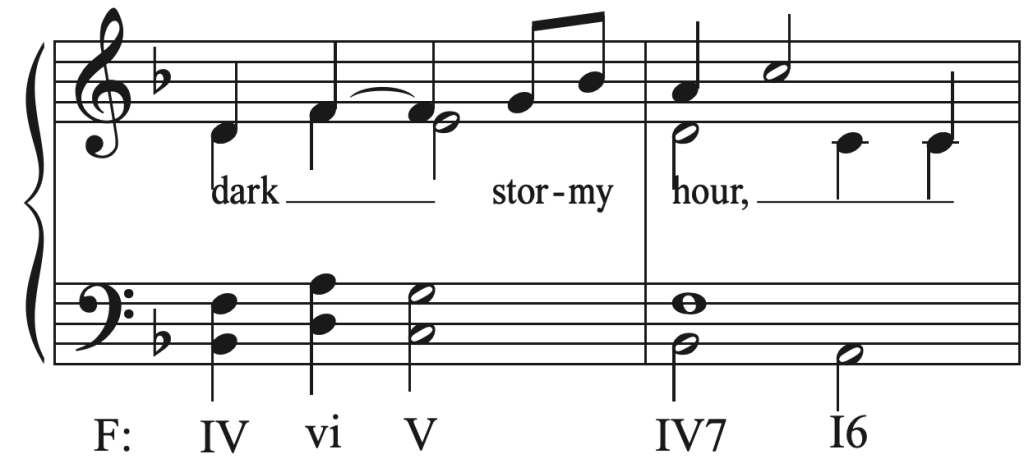

The opening of Frank Ticheli’s “Earth Song” may be heard as tonally ambiguous, particularly since there are consistent E-flats marked despite the one-flat key signature. However, the accidentals disappear in m. 9, and the chord progression more clearly establishes the tonic as F major. Since m. 1 is essentially the same notes as m. 9 but transposed up a fourth, this suggests that the opening might be heard in B-flat major, a fourth up from F major. This establishes those opening chords as IV vi V. Since V chords tend to move to I but this progression merely repeats, this opening progression sounds like it is searching for something that never materializes, like the elusive “peace” referenced at the end.

The end of “Earth Song” is striking. The majority of the piece centers around the IV vi V progression shown above. This progression occurs in mm. 40–41 in F major. The progression sequences down a step to iii V IV in m. 42. M. 43 goes iii V II, with a surprising major II chord. While this chord is surprising, it is similar to the progression in mm. 7–8 (in B-flat major). M. 44 is the biggest surprise: the B in the alto voice remains as a common tone as the remaining voices move by step or third into an E major chord on the word “peace,” a half-step down from the tonic of the piece as a whole. As most of the piece, outside of an ambiguous beginning section, is written in F major, ending in E major, a key completely unrelated to F major, comes as a surprise to listeners. The chord progression leading up to measures 44 and 45 creates a sense of mystery and confusion moving towards a resolution; having an ending on a major I chord in a different key produces a text painting of peace on the final word of the piece, “peace”.

Example 2: Pitch centricity and chord progressions in “She Weeps Over Rahoon”

In Eric Whitacre’s “She Weeps Over Rahoon,” the music centers around a single chord at a time but there are important chord shifts, following the circle of fifths.

At the very end of the song, either C or G could be heard as a tonal center. In this final section, the choir is singing notes from both G major and C minor chords, and the piano accompaniment is similar to the opening of the piece, which seemed to establish a G tonic. In m. 34, the horn part ends on a D, which fits better in G major. The final note of the piece, however, is a low C in the piano. Still, G can be heard as the final note in the right hand of the piano.

Example 3: Chords contributing to the effect of “Music of Stillness”

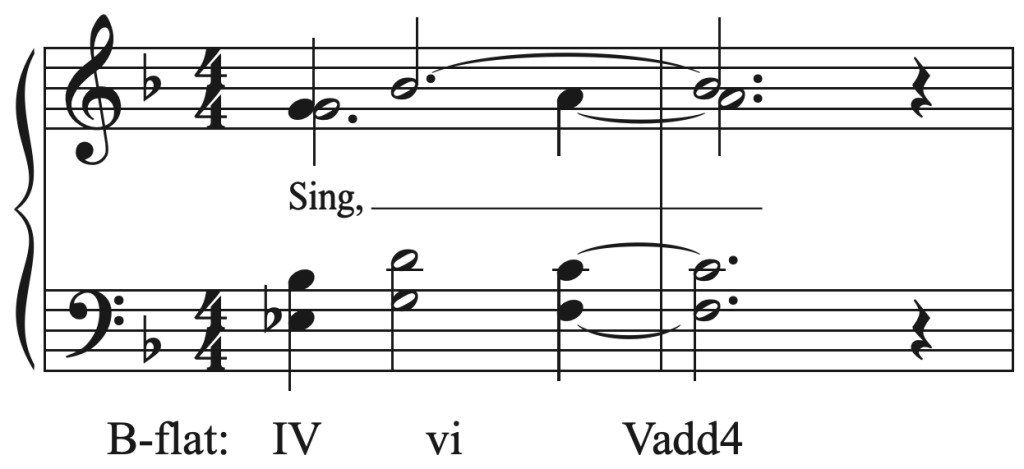

The IV chord, when emphasized, can feel relaxed and nostalgic. In the piece “Music of Stillness” by Elaine Hagenberg, this chord is found throughout. The first section is annotated below.

The phrase begins on I and ends on IV with the word “rest”. Throughout the entirety of the piece, I, IV, and vi chords are used, allowing emphasis to be placed on the tonic. Along with this, many of the chords have an added 2. For example, in the first measure of the piece, the first chord is a I chord moving to a IV chord. Both chords have tonic in them, creating an overall sense of 1, but also conjures an unsettling feeling as tonic plays a different role in each chord. The IV chord provides a calming and tranquil emotion combined with the word “rest,” and with the other two chords that share the relaxed tonic note, I and vi.

Example 4: Dissonance in “Weep No More”

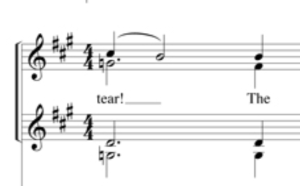

In the piece “Weep No More” by David Childs, almost each time the word “tear” appears in the text, there is a chromatic pattern. For example, in mm. 5 and 6, the altos step from an F sharp to a G natural allowing listeners to hear a leading tone to tonic relationship. The top soprano part revolves in the second beat of m. 6. A couple measures later, the bottom soprano line progresses from an A to a G natural, creating a dissonant sounding chord and causing the words “no tear” to stand out to listeners.

What also stands out about this particular part is the chord progression surrounding “tear”. The piece starts with an F minor chord with the top soprano and bottom alto moving in the second beat to create a tritone. In the third beat, the parts return to the F minor chord, this time in first inversion. The first beat of m. 6 displays dissonance in all parts with a G and A in the middle voices and a D and C in the outer voices. In the second beat of the same measure, a G diminished chord is created before moving onto the next phrase.

This chord progression is repeated again a few measures later on the same words. This progression creates a beautiful yet fragile appearance at the start. Especially with the minor quality of the piece, the tritone in m. 5, and the dissonance in m. 6, listeners can begin to feel the breathlessness and gentleness of the piece.

Example 5: Harmonic Navigation of “O sacrum convivium”

Upon first glance, the accidentals and the piano is overwhelming, and makes it hard to find a general key for this part of the piece. Analyzing each chord separately and the top and bottom voices separately aids singers in hearing chords and matching them while not getting their part confused with the others’.

At rehearsal 6, the top and bottom voices are moving away from each other, the Tenor 2 line being the exception. As the piano is for rehearsal purposes only, it plays all parts. Looking at the piano for the first beat, the treble voices are singing an F major chord and the base voices are singing a Bb third. The next beat has a G chord in the top and an Ab chord in the bottom. Both these chords are clashing and almost every note in an 8 note scale is being played, but looking at the chords and parts this way rather than in a key or the entirety of the piano line at the same time allows for the director to hear the chords and hear the chords in the choir.

Another way to analyze specifically the measure of rehearsal 6 includes looking at the top voices, plus the tenor voice, as ascending triads, and the bottom voices as descending triads. This helps in manipulating the quality of the sound the piece calls for.

It might be difficult to hear that it is two different major chords going in different directions on the staff, but looking at the sheet music, it is much more clear to see that pattern in the visual music.