“Afternoon on a Hill” by Eric Barnum

Julianne Larson

Introduction

“Afternoon on a Hill” with text by Edna St. Vincent Millay and music by Eric William Barnum is a 2008 choral piece written for SATB and piano. Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) was an accomplished poet and playwright, having published this text in her first poetry collection in 1917. She was the first woman to receive the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1923. Eric William Barnum (b. 1979) holds an advanced degree in conducting from Minnesota State, and two BAs in Composition and Vocal Performance from Bemidji State. He is currently the Director of Choral Activities at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa.

Overview

“Afternoon on a Hill” is a contemporary choral piece with a contemplative tone that complements Edna St. Vincent Milay’s jovial text. It is filled with opportunities for expressive singing and phrase shaping.

I will be the gladdest thing Under the sun! I will touch a hundred flowers And not pick one.

I will look at cliffs and clouds With quiet eyes, Watch the wind bow down the grass, And the grass rise. And when lights begin to show Up from the town, I will mark which must be mine, And then start down!

Analysis

Form

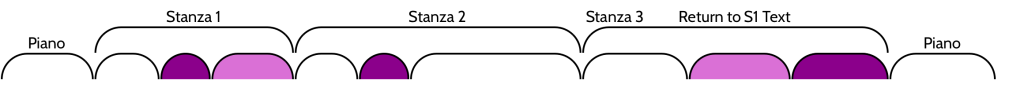

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the form is a motif that first appears at measure 12 but reappears multiple times, shown in darker purple in the diagram above. It is sung on either an ooo or an ah, but more often on an ooo so I will call it the “ooo motif”. This motif feels driven to me, not entirely content to rest peacefully. It not only moves somewhat quickly, and keeps moving the entire time, but the piano accompaniment adopts a lowered scale degree 6, making the accompaniment sound minor against the solidly major melody. This to me signals the melody’s refusal to settle for a boring and passive happiness. I initially was confused as to why this section sounds the very slightest bit unsettled, but this text is all about intentionally making the choice to be happy. This melody cannot be content with passivity or indifference. This motif could possibly represent the determination of the speaker, driving the piece forward as the speaker strives towards happiness.

The higher purple bubbles in the diagram above represent the lines “I will touch a hundred flowers and not pick one,” which are first presented as part of Stanza 1 but then repeated after Stanza 3 to bring the text to a close before the final “ooo motif.”

Text

This text is a passionate exclamation of the speaker’s determination to be happy. Nothing about this text is passive, each stanza describing an action the speaker will take. An important thing to note about the text is that it is in alternating trochaic tetrameter and trochaic trimeter: strong, weak, strong, weak, strong / strong, strong, weak, strong. One line in particular seems very important to the composer: “I will touch a hundred flowers / And not pick one.” This line is sung in two different sections of the piece. It is a beautiful representation of the speaker actively choosing peace, rejecting even the small violence of picking a flower.

Texture

A large portion of this piece falls into the “wall of sound” category, where there is no one clear melody to highlight. These are moments where all parts are singing the same text with the same rhythm. In the other portions of the piece, however, it is very clear which part should pull focus. Particularly in the “I will look at cliffs and clouds” section at the beginning of Stanza 2, each part takes turns singing the text. We can also always count on whichever part is singing the “ooo motif” to be most important. It’s important to treat the piano accompaniment as its own important line throughout, as it has a big part to play in telling the story. Moments where the piano part is particularly independent include under the “ooo motif” and on page seven with, “I watch the wind bow down the grass.” Here, the pianist is given a few tones and told to play them as randomly as possible.

Rhythm/Meter

This piece has a handful of meter changes (most only lasting a measure), but is most often in 4/4. From a listener’s perspective, the piece is not so clearly in four for the opening: held out piano chords make it difficult to feel the meter, this ambiguity continuing even into the entrance of the choir. There’s a pause after seven beats on “I will be the gladdest thing,” then another pause after three beats on “under the sun.” After this opening, though, the quadruple meter is quite clear, excepting a few written meter changes. The most significant meter change is on page 10, with the two nonconsecutive measures of 5/4 on the return of the words “touch a hundred flowers.” This change gives an extra beat to the syllable “hun”, which is also the highest note of the phrase. This is a sort of time-stopping moment for the audience to drink in the rich fullness of the chord. I think the choice to use a time signature change rather than a fermata was to ensure the movement of the piece is not lost. The tempo at this moment reads, “flying.” Barnum wanted a metrical emphasis on the note, but did not want the phrase to lose its momentum.

Harmony

There are lots of add2, add7, and add9 chords, which aren’t found much in traditional choral music, but are fairly standard for contemporary. This piece is largely in D major, with a significant modulation to G major at measure 50, then a return back to D major. The modulation happens at a climactic moment of the piece, the arrival point for the ascending phrase. We have arrived at another decision for the speaker; this modulation occurs on the word “town,” leading into the line, “I will mark which must be mine.” Another harmonically significant moment occurs on page 3 during the “I will look at cliffs and clouds” section. The lowered scale degree 6 we saw with the “ooo motif” has returned, giving this section the same unsettled feeling. This section culminates in a triumphant return of the “ooo motif” (though this time on an ah).

Teaching

This piece could be very helpful in teaching standards such as Utah’s L1.MC.P.2 (p. 77): “Discuss, with guidance, various elements of a musical work such as form, phrasing, and style.” The pitches of this piece are, for the most part, not exceptionally difficult to learn, so it becomes about shaping the work musically. A teacher might discuss with their choir how they can use tools like dynamics and articulation to shape a phrase. This piece could also be useful in teaching Standard L1.MC.R.2 (p. 78): “Identify and discuss how musical elements are embedded within a musical work to express possible meanings, and consider how the use of musical elements helps predict the composer’s possible intent.” Invite your choir to give their own interpretations to the text, and how the composer’s choices enhance its meaning. Discuss what they think the “ooo motif” symbolizes and why it is important.

Rehearsal

A difficult moment, pitch-wise, can be found on page seven during the “I watch the wind bow down the grass”, where the altos are split between a C# and a D. This dissonance is going to be hard to get exactly right. The pitches are relatively easy to find most elsewhere in this piece. Another moment that may be difficult to get right is the slides on page eight. The score instructs that the slides happen evenly and start immediately upon hitting the note. Especially if a large ensemble is performing this piece, it can be tricky to ensure everyone starts their ascent and arrives at the top note at the same time. Rhythmically, this piece won’t give most ensembles too much trouble, but ensure that the singers are paying attention to the small meter changes like the measures of 5/4 on page 10.

Performance

One aspect of performance that I think is very important is that this piece not drag at all. Barnum has very strategically used written meter changes rather than fermatas to simultaneously emphasize important moments and keep it moving. The “ooo motif” is one place that certainly has the potential to drag. Some might feel tempted to lean into the lilting melody and slow down, but it’s very important that it stays driven. As discussed before, this piece has an innate determined quality to it, and the meaning of the text could be undermined if it loses its momentum. Performers should also pay close attention to the dynamic markings throughout. There are many markings, and an especially large amount of diminuendos and crescendos. This both encourages emotional singing and phrase shaping