Texture: Discussion and Examples

Abigail Tilton and Elizabeth Wilson

As we go through a few pieces together in this next section and try to label different textures, please note:

- These definitions of textures are very generalized. It might be hard for real-life examples to perfectly fit these definitions.

- There are some textures that are not identifiable by the definitions provided, meaning that our definitions do not touch on all the different characteristics of other textures. This being said, it can still be useful to take the time to analyze these textures, as it will help create a better understanding of how the piece is characterized as well as how to approach it from a balance standpoint.

To further understand how to analyze textures, we will apply our steps of approach by looking at smaller sections of different pieces, and then move into a full analysis of a selected piece.Looking at “Earth Song” by Frank Ticheli, there is a section (mm. 26-32) where all parts are singing in homorhythmic texture. However, the melodic line (found in the soprano part) is easy to point out because it has larger intervals than any other voice part. After identifying both the texture and the melody, we can now make decisions on how to balance the choir to bring out said melody. Something that makes this section interesting is how it changes from what happens before this section. From the beginning through measure 25, all four vocal parts are singing. When arriving at measure 26, the basses drop out which dramatically changes the texture. As a performer, this is an opportunity to completely change the feel of this section to emulate the “dolce” marking.

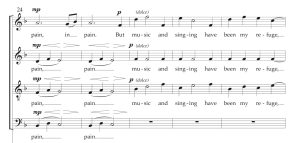

Another great example to look at is Fire Flowers by Timothy Corlis. The texture in the final section beginning at measure 52 , shown below, is polyphonic. It is clear that the soprano 2 line has the melody, due to the fact it has the new lyrics. However, it is not the only part that needs to be emphasized at this moment. The alto 2 line begins a theme that is repeated and eventually joined by each part until every part is singing it in canon, as shown in the second example below. Even though the alto 2 line at measure 52 is not the melody, it would be helpful to emphasize this line somewhat to the listener in order to foreshadow this ending. As a director, it is a valuable use of your time to analyze a piece before you present it to your group, so you and your performers have a greater understanding of how you are going to approach that piece.

Now, let’s take a look at a specific piece in-depth and some ways to approach a performance of it.

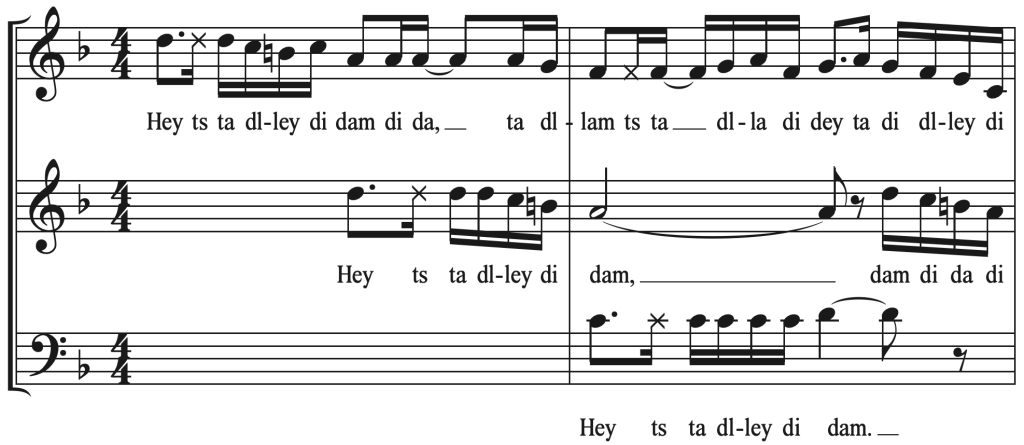

As a director, working through a piece like Turlutte Acadienne Montréalaise requires more thought than a typical piece because it doesn’t have a text with meaning, and therefore you cannot just focus on who is saying the “most important” text. Working on a piece with meaningless syllables requires a director to analyze the texture. In Turlutte, the vast majority of the piece is homophonic, but the melody regularly jumps from part to part. You must identify these sections accurately in order to properly perform the piece. As mentioned previously, the best way to identify a “melody line” in an unfamiliar piece is to look at what part moves around the most.

The piece very clearly begins in monophony, which also helps us identify the melody in later parts. The alto section takes over the melody measure 7-14, and then the melody switches to the bass until measure 22. This idea of passing the melody from part to part continues throughout the majority of the song, as depicted by the table below.

| mm. 1-6 | mm. 6-17 | mm. 18-22 | mm. 23-37 | mm. 38-46 | mm. 47-54 | mm. 55-61 | mm. 62-71 |

| Monophony | Alto Melody | Bass Melody | Alto Melody | Soprano Melody | Melody Switches Frequently | Homorhythmic | Soprano Melody |