14.4 Seed Plants: Angiosperms

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the main parts of a flower and their purpose

- Detail the life cycle of an angiosperm

- Discuss the two main groups into which flower plants are divided, as well as explain how basal angiosperms differ from others

From their humble and still obscure beginning during the early Jurassic period (202–145.5 MYA), the angiosperms, or flowering plants, have successfully evolved to dominate most terrestrial ecosystems. Angiosperms include a staggering number of genera and species; with more than 260,000 species, the division is second only to insects in terms of diversification (Figure 14.24).

Angiosperm success is a result of two novel structures that ensure reproductive success: flowers and fruit. Flowers allowed plants to form cooperative evolutionary relationships with animals, in particular insects, to disperse their pollen to female gametophytes in a highly targeted way. Fruit protect the developing embryo and serve as an agent of dispersal. Different structures on fruit reflect the dispersal strategies that help with the spreading of seeds.

Flowers

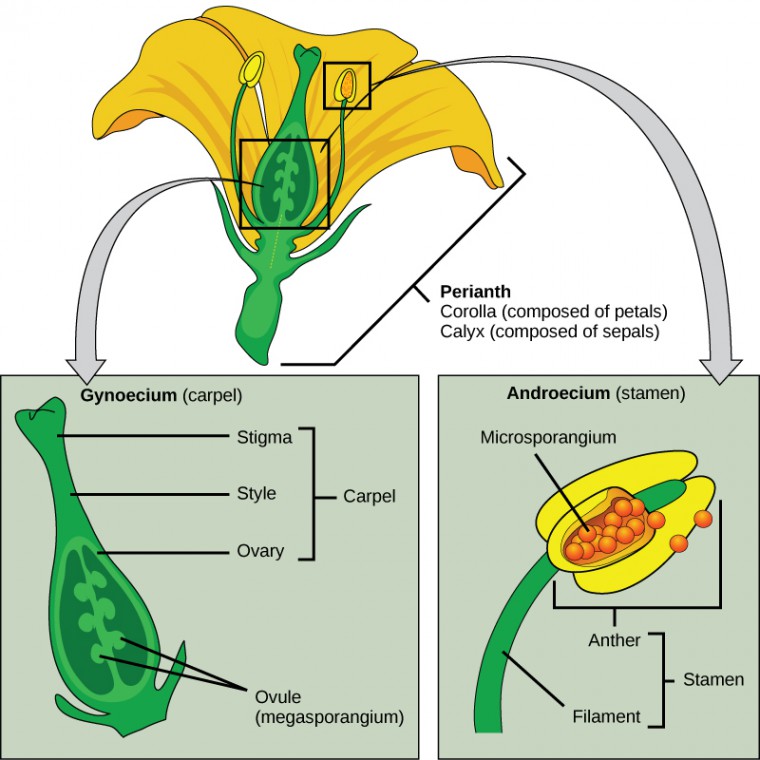

Flowers are modified leaves or sporophylls organized around a central stalk. Although they vary greatly in appearance, all flowers contain the same structures: sepals, petals, pistils, and stamens. A whorl of sepals (the calyx) is located at the base of the peduncle, or stem, and encloses the floral bud before it opens. Sepals are usually photosynthetic organs, although there are some exceptions. For example, the corolla in lilies and tulips consists of three sepals and three petals that look virtually identical—this led botanists to coin the word tepal. Petals (collectively the corolla) are located inside the whorl of sepals and usually display vivid colors to attract pollinators. Flowers pollinated by wind are usually small and dull. The sexual organs are located at the center of the flower.

As illustrated in Figure 14.25, the stigma, style, and ovary constitute the female organ, the carpel or pistil, which is also referred to as the gynoecium. A gynoecium may contain one or more carpels within a single flower. The megaspores and the female gametophytes are produced and protected by the thick tissues of the carpel. A long, thin structure called a style leads from the sticky stigma, where pollen is deposited, to the ovary enclosed in the carpel. The ovary houses one or more ovules that will each develop into a seed upon fertilization. The male reproductive organs, the androecium or stamens, surround the central carpel. Stamens are composed of a thin stalk called a filament and a sac-like structure, the anther, in which microspores are produced by meiosis and develop into pollen grains. The filament supports the anther.

Fruit

The seed forms in an ovary, which enlarges as the seeds grow. As the seed develops, the walls of the ovary also thicken and form the fruit. In botany, a fruit is a fertilized and fully grown, ripened ovary. Many foods commonly called vegetables are actually fruit. Eggplants, zucchini, string beans, and bell peppers are all technically fruit because they contain seeds and are derived from the thick ovary tissue. Acorns and winged maple keys, whose scientific name is a samara, are also fruit.

Mature fruit can be described as fleshy or dry. Fleshy fruit include the familiar berries, peaches, apples, grapes, and tomatoes. Rice, wheat, and nuts are examples of dry fruit. Another distinction is that not all fruits are derived from the ovary. Some fruits are derived from separate ovaries in a single flower, such as the raspberry. Other fruits, such as the pineapple, form from clusters of flowers. Additionally, some fruits, like watermelon and orange, have rinds. Regardless of how they are formed, fruits are an agent of dispersal. The variety of shapes and characteristics reflect the mode of dispersal. The light, dry fruits of trees and dandelions are carried by the wind. Floating coconuts are transported by water. Some fruits are colored, perfumed, sweet, and nutritious to attract herbivores, which eat the fruit and disperse the tough undigested seeds in their feces. Other fruits have burs and hooks that cling to fur and hitch rides on animals.

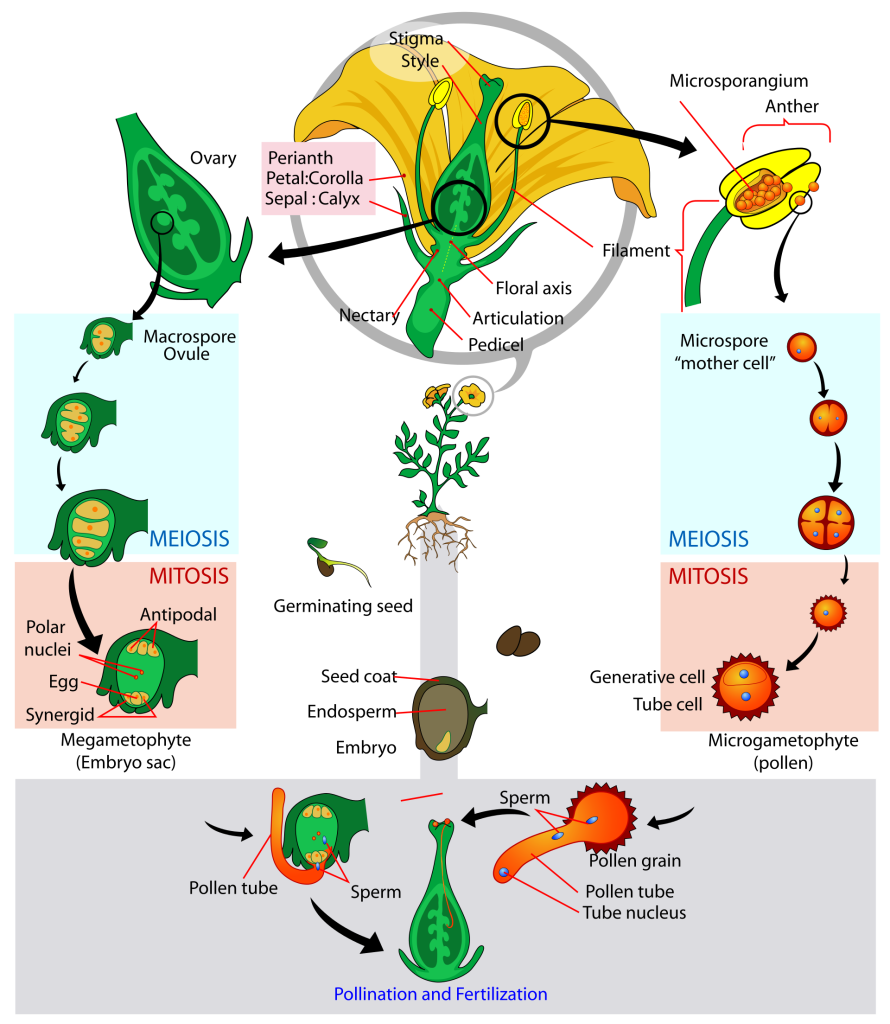

The Life Cycle of an Angiosperm

The adult, or sporophyte, phase is the main phase in an angiosperm’s life cycle. Like gymnosperms, angiosperms are heterosporous. They produce microspores, which develop into pollen grains (the male gametophytes), and megaspores, which form an ovule containing the female gametophytes. Inside the anthers’ microsporangia (Figure 14.26), male microsporocytes divide by meiosis, generating haploid microspores that undergo mitosis and give rise to pollen grains. Each pollen grain contains two cells: one generative cell that will divide into two sperm, and a second cell that will become the pollen tube cell.

Visual Connection

If a flower lacked a megasporangium, what type of gamete would it not be able to form? If it lacked a microsporangium, what type of gamete would not form?

(Answer: Without a megasporangium, an egg would not form; without a microsporangium, pollen would not form.)

In the ovules, the female gametophyte is produced when a megasporocyte undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid megaspores. One of these is larger than the others and undergoes mitosis to form the female gametophyte or embryo sac. Three mitotic divisions produce eight nuclei in seven cells. The egg and two cells move to one end of the embryo sac (gametophyte) and three cells move to the other end. Two of the nuclei remain in a single cell and fuse to form a 2n nucleus; this cell moves to the center of the embryo sac.

When a pollen grain reaches the stigma, a pollen tube extends from the grain, grows down the style, and enters through an opening in the integuments of the ovule. The two sperm cells are deposited in the embryo sac.

What occurs next is called a double fertilization event (Figure 14.27) and is unique to angiosperms. One sperm and the egg combine, forming a diploid zygote—the future embryo. The other sperm fuses with the diploid nucleus in the center of the embryo sac, forming a triploid cell that will develop into the endosperm: a tissue that serves as a food reserve. The zygote develops into an embryo with a radicle, or small root, and one or two leaf-like organs called cotyledons. Seed food reserves are stored outside the embryo, and the cotyledons serve as conduits to transmit the broken-down food reserves to the developing embryo. The seed consists of a toughened layer of integuments forming the coat, the endosperm with food reserves and, at the center, the well-protected embryo.

Most flowers carry both stamens and carpels; however, a few species self-pollinate. These are known as “perfect” flowers because they contain both types of sex organs (Figure 14.25]. Biochemical and anatomical barriers to self-pollination promote cross-pollination. Self-pollination is a severe form of inbreeding, and can increase the number of genetic defects in offspring.

A plant may have perfect flowers, and thus have both genders in each flower; or, it may have imperfect flowers of both kinds on one plant (Figure 14.28). In each case, such species are called monoecious plants, meaning “one house.” Some botanists refer to plants with perfect flowers simply as hermaphroditic. Some plants are dioecious, meaning “two houses,” and have male and female flowers (“imperfect flowers”) on different plants. In these species, cross-pollination occurs all the time.

Diversity of Angiosperms

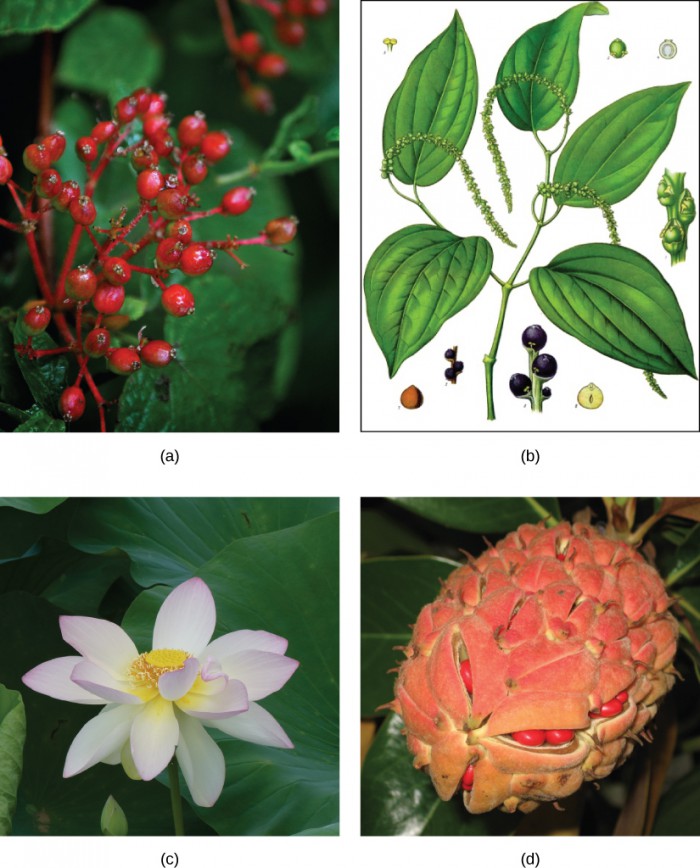

Angiosperms are classified in a single division, the Anthophyta. Modern angiosperms appear to be a monophyletic group, which means that they originate from a single ancestor. Flowering plants are divided into two major groups, according to the structure of the cotyledons, the pollen grains, and other features: monocots, which include grasses and lilies, and eudicots or dicots, a polyphyletic group. Basal angiosperms are a group of plants that are believed to have branched off before the separation into monocots and eudicots because they exhibit traits from both groups. They are categorized separately in many classification schemes, and correspond to a grouping known as the Magnoliidae. The Magnoliidae group is comprised of magnolia trees, laurels, water lilies, and the pepper family.

Basal Angiosperms

The Magnoliidae are represented by the magnolias: tall trees that bear large, fragrant flowers with many parts, and are considered archaic (Figure 14.29d). Laurel trees produce fragrant leaves and small inconspicuous flowers. The Laurales are small trees and shrubs that grow mostly in warmer climates. Familiar plants in this group include the bay laurel, cinnamon, spice bush (Figure 14.29a), and the avocado tree. The Nymphaeales are comprised of the water lilies, lotus (Figure 14.29c), and similar plants. All species of the Nymphaeales thrive in freshwater biomes, and have leaves that float on the water surface or grow underwater. Water lilies are particularly prized by gardeners, and have graced ponds and pools since antiquity. The Piperales are a group of herbs, shrubs, and small trees that grow in tropical climates. They have small flowers without petals that are tightly arranged in long spikes. Many species are the source of prized fragrances or spices; for example, the berries of Piper nigrum (Figure 14.29b) are the familiar black pepper that is used to flavor many dishes.

Monocots

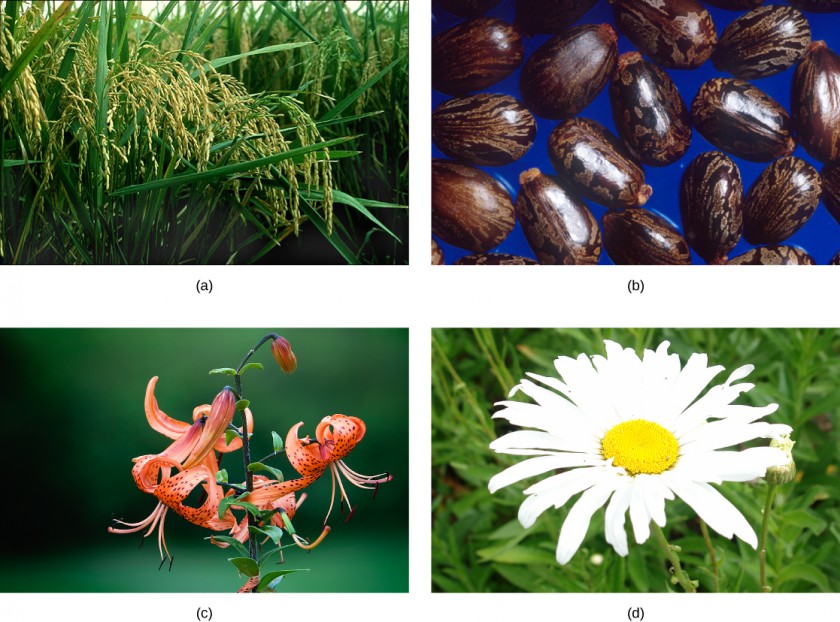

Plants in the monocot group have a single cotyledon in the seedling, and also share other anatomical features. Veins run parallel to the length of the leaves, and flower parts are arranged in a three- or six-fold symmetry. The pollen from the first angiosperms was monosulcate (containing a single furrow or pore through the outer layer). This feature is still seen in the modern monocots. True woody tissue is rarely found in monocots, and the vascular tissue of the stem is not arranged in any particular pattern. The root system is mostly adventitious (unusually positioned) with no major taproot. The monocots include familiar plants such as the true lilies (not to be confused with the water lilies), orchids, grasses, and palms. Many important crops, such as rice and other cereals (Figure 14.30a), corn, sugar cane, and tropical fruit, including bananas and pineapple, belong to the monocots.

Eudicots

Eudicots, or true dicots, are characterized by the presence of two cotyledons. Veins form a network in leaves. Flower parts come in four, five, or many whorls. Vascular tissue forms a ring in the stem. (In monocots, vascular tissue is scattered in the stem.) Eudicots can be herbaceous (like dandelions or violets), or produce woody tissues. Most eudicots produce pollen that is trisulcate or triporate, with three furrows or pores. The root system is usually anchored by one main root developed from the embryonic radicle. Eudicots comprise two-thirds of all flowering plants. Many species seem to exhibit characteristics that belong to either group; therefore, the classification of a plant as a monocot or a eudicot is not always clearly evident (Table 14.1).

Table 14.1 Comparision of Structural Characteristic of Monocots and Eudicots

| Comparison of Structural Characteristics of Monocots and Eudicots | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Monocot | Eudicot |

| Cotyledon | One | Two |

| Veins in leaves | Parallel | Network ( branched) |

| Vascular tissue | Scattered | Arranged in ring pattern |

| Roots | Network of adventitious roots | Tap root with many lateral roots |

| Pollen | Monosulcate | Trisulcate |

| Flower parts | Three or multiple of three | Four, five, multiple of four or five and whorls |

Concept in Action

Explore this website for more information on pollinators.

The Role of Seed Plants

Without seed plants, life as we know it would not be possible. Plants play a key role in the maintenance of terrestrial ecosystems through the stabilization of soils, cycling of carbon, and climate moderation. Large tropical forests release oxygen and act as carbon dioxide “sinks.” Seed plants provide shelter to many life forms, as well as food for herbivores, thereby indirectly feeding carnivores. Plant secondary metabolites are used for medicinal purposes and industrial production. Virtually all animal life is dependent on plants for survival.

Animals and Plants: Herbivory

Coevolution of flowering plants and insects is a hypothesis that has received much attention and support, especially because both angiosperms and insects diversified at about the same time in the middle Mesozoic. Many authors have attributed the diversity of plants and insects to both pollination and herbivory, or the consumption of plants by insects and other animals. Herbivory is believed to have been as much a driving force as pollination. Coevolution of herbivores and plant defenses is easily and commonly observed in nature. Unlike animals, most plants cannot outrun predators or use mimicry to hide from hungry animals (although mimicry has been used to entice pollinators). A sort of arms race exists between plants and herbivores. To “combat” herbivores, some plant seeds—such as acorn and unripened persimmon—are high in alkaloids and therefore unsavory to some animals. Other plants are protected by bark, although some animals developed specialized mouth pieces to tear and chew vegetal material. Spines and thorns deter most animals, except for mammals with thick fur, and some birds have specialized beaks to get past such defenses.

Herbivory has been exploited by seed plants for their own benefit. The dispersal of fruits by herbivorous animals is a striking example of mutualistic relationships. The plant offers to the herbivore a nutritious source of food in return for spreading the plant’s genetic material to a wider area.

Animals and Plants: Pollination

More than 80 percent of angiosperms depend on animals for pollination (technically the transfer of pollen from the anther to the stigma). Consequently, plants have developed many adaptations to attract pollinators. With over 200,000 different plants dependent on animal pollination, the plant needs to advertise to its pollinators with some specificity. The specificity of specialized plant structures that target animals can be very surprising. It is possible, for example, to determine the general type of pollinators favored by a plant by observing the flower’s physical characteristics. Many bird or insect-pollinated flowers secrete nectar, which is a sugary liquid. They also produce both fertile pollen, for reproduction, and sterile pollen rich in nutrients for birds and insects. Many butterflies and bees can detect ultraviolet light, and flowers that attract these pollinators usually display a pattern of ultraviolet reflectance that helps them quickly locate the flower’s center. In this manner, pollinating insects collect nectar while at the same time are dusted with pollen. Large, red flowers with little smell and a long funnel shape are preferred by hummingbirds, who have good color perception, a poor sense of smell, and need a strong perch. White flowers that open at night attract moths. Other animals—such as bats, lemurs, and lizards—can also act as pollinating agents. Any disruption to these interactions, such as the disappearance of bees, for example as a consequence of colony collapse disorders, can lead to disaster for agricultural industries that depend heavily on pollinated crops.

The Importance of Seed Plants in Human Life

Seed plants are the foundation of human diets across the world. Many societies eat almost exclusively vegetarian fare and depend solely on seed plants for their nutritional needs. A few crops (rice, wheat, and potatoes) dominate the agricultural landscape. Many crops were developed during the agricultural revolution, when human societies made the transition from nomadic hunter–gatherers to horticulture and agriculture. Cereals, rich in carbohydrates, provide the staple of many human diets. Beans and nuts supply proteins. Fats are derived from crushed seeds, as is the case for peanut and rapeseed (canola) oils, or fruits

The medicinal properties of plants have been known to human societies since ancient times. There are references to the use of plants’ curative properties in Egyptian, Babylonian, and Chinese writings from 5,000 years ago. Many modern synthetic therapeutic drugs are derived or synthesized from plant secondary metabolites. Very often, the raw form of the plant or plant-based substance may be unusable even if it demonstrates helpful properties. For example, chaulmoogra oil was somewhat effective for treating leprosy, but it was difficult to apply and painful for patients. In 1915, Alice Ball (at only 23 years old), created a method for extracting the active ester compounds from the oil so that it could be absorbed by the body, creating a much more effective treatment without the negative side effects. The “Ball Technique” remained the preferred method until synthetic medicines replaced it decades later. It is important to note that the same plant extract can be a therapeutic remedy at low concentrations, become an addictive drug at higher doses, and can potentially kill at high concentrations. Table 14.2 presents a few drugs, their plants of origin, and their medicinal applications.

| Plant | Compound | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Deadly nightshade ( Atropa belladonna ) | Atropine | Dilate eye pupils for eye exams |

| Foxglove ( Digitalis purpurea ) | Digitalis | Heart disease, stimulates heart beat |

| Yam ( Dioscorea spp.) | Steroids | Steroid hormones: contraceptive pill and cortisone |

| Ephedra ( Ephedra spp.) | Ephedrine | Decongestant and bronchiole dilator |

| Pacific yew ( Taxus brevifolia ) | Taxol | Cancer chemotherapy; inhibits mitosis |

| Opium poppy ( Papaver somniferum ) | Opioids | Analgesic (reduces pain without loss of consciousness) and narcotic (reduces pain with drowsiness and loss of consciousness) in higher doses |

| Quinine tree ( Cinchona spp.) | Quinine | Antipyretic (lowers body temperature) and antimalarial |

| Willow ( Salix spp.) | Salicylic acid (aspirin) | Analgesic and antipyretic |

Section Summary

Angiosperms are the dominant form of plant life in most terrestrial ecosystems, comprising about 90 percent of all plant species. Most crop and ornamental plants are angiosperms. Their success results, in part, from two innovative structures: the flower and the fruit. Flowers are derived evolutionarily from modified leaves. The main parts of a flower are the sepals and petals, which protect the reproductive parts: the stamens and the carpels. The stamens produce the male gametes, which are pollen grains. The carpels contain the female gametes, which are the eggs inside ovaries. The walls of the ovary thicken after fertilization, ripening into fruit that can facilitate seed dispersal.

Angiosperms’ life cycles are dominated by the sporophyte stage. Double fertilization is an event unique to angiosperms. The flowering plants are divided into two main groups—the monocots and eudicots—according to the number of cotyledons in the seedlings. Basal angiosperms belong to a lineage older than monocots and eudicots.

Glossary

- anther: a sac-like structure at the tip of the stamen in which pollen grains are produced

- Anthophyta: the division to which angiosperms belong

- basal angiosperms: a group of plants that probably branched off before the separation of monocots and eudicots

- calyx: the whorl of sepals

- carpel: the female reproductive part of a flower consisting of the stigma, style, and ovary

- corolla: the collection of petals

- cotyledon: the one (monocot) or two (dicot) primitive leaves present in a seed

- dicot: a group of angiosperms whose embryos possess two cotyledons; also known as eudicot

- eudicots: a group of angiosperms whose embryos possess two cotyledons; also known as dicot

- filament: the thin stalk that links the anther to the base of the flower

- gynoecium: the group of structures that constitute the female reproductive organ; also called the pistil

- herbaceous: describes a plant without woody tissue

- monocot: a related group of angiosperms that produce embryos with one cotyledon and pollen with a single ridge

- ovary: the chamber that contains and protects the ovule or female megasporangium

- petal: a modified leaf interior to the sepal; colorful petals attract animal pollinator

- pistil: the group of structures that constitute the female reproductive organ; also called the carpel

- sepal: a modified leaf that encloses the bud; outermost structure of a flower

- stamen: the group of structures that contain the male reproductive organs

- stigma: uppermost structure of the carpel where pollen is deposited

- style: the long thin structure that links the stigma to the ovary

Media Attributions

- Figure 14.24 © Myriam Feldman; OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 14.25 © Modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal; OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 14.26 © Modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal; OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 14.28 © (a) Modification of work by Liz West; (c) Modification of work by Scott Zona; OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 14.29 © (a) Modification of work by Cory Zanker; (b) Modification of work by Franz Eugen Köhler; (c) Modification of work by "berduchwal"/Flickr; (d) Modification of work by "Coastside2"/Wikimedia Commons; OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 14.30 © (a) Modification of work by David Nance; (b) Modification of work by USDA, ARS; (c) Modification of work by "longhorndave"/Flickr; (d) Modification of work by "Cellulaer"/NinjaPhoto; OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license