11.1 Discovering How Populations Change

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how Darwin’s theory of evolution differed from the current view at the time

- Describe how the present-day theory of evolution was developed

- Describe how population genetics is used to study the evolution of populations

The theory of evolution by natural selection describes a mechanism for species change over time. That species change had been suggested and debated well before Darwin. The view that species were static and unchanging was grounded in the writings of Plato, yet there were also ancient Greeks that expressed evolutionary ideas.

In the eighteenth century, ideas about the evolution of animals were reintroduced by the naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon and even by Charles Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus Darwin. During this time, it was also accepted that there were extinct species. At the same time, James Hutton, the Scottish naturalist, proposed that geological change occurred gradually by the accumulation of small changes from processes (over long periods of time) just like those happening today. This contrasted with the predominant view that the geology of the planet was a consequence of catastrophic events occurring during a relatively brief past. Hutton’s view was later popularized by the geologist Charles Lyell in the nineteenth century. Lyell became a friend to Darwin and his ideas were very influential on Darwin’s thinking. Lyell argued that the greater age of Earth gave more time for gradual change in species, and the process provided an analogy for gradual change in species.

In the early nineteenth century, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck published a book that detailed a mechanism for evolutionary change that is now referred to as inheritance of acquired characteristics. In Lamarck’s theory, modifications in an individual caused by its environment, or the use or disuse of a structure during its lifetime, could be inherited by its offspring and, thus, bring about change in a species. While this mechanism for evolutionary change as described by Lamarck was discredited, Lamarck’s ideas were an important influence on evolutionary thought. The inscription on the statue of Lamarck that stands at the gates of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris describes him as the “founder of the doctrine of evolution.”

Charles Darwin and Natural Selection

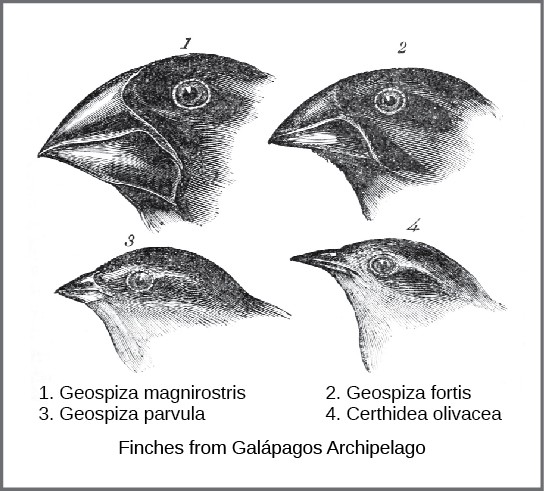

The actual mechanism for evolution was independently conceived of and described by two naturalists, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace, in the mid-nineteenth century. Importantly, each spent time exploring the natural world on expeditions to the tropics. From 1831 to 1836, Darwin traveled around the world on H.M.S. Beagle, visiting South America, Australia, and the southern tip of Africa. Wallace traveled to Brazil to collect insects in the Amazon rainforest from 1848 to 1852 and to the Malay Archipelago from 1854 to 1862. Darwin’s journey, like Wallace’s later journeys in the Malay Archipelago, included stops at several island chains, the last being the Galápagos Islands (west of Ecuador). On these islands, Darwin observed species of organisms on different islands that were clearly similar, yet had distinct differences. For example, the ground finches inhabiting the Galápagos Islands comprised several species that each had a unique beak shape (Figure 11.2). He observed both that these finches closely resembled another finch species on the mainland of South America and that the group of species in the Galápagos formed a graded series of beak sizes and shapes, with very small differences between the most similar. Darwin imagined that the island species might be all species modified from one original mainland species. In 1860, he wrote, “Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.”1

Wallace and Darwin both observed similar patterns in other organisms and independently conceived a mechanism to explain how and why such changes could take place. Darwin called this mechanism natural selection. Natural selection, Darwin argued, was an inevitable outcome of three principles that operated in nature. First, the characteristics of organisms are inherited, or passed from parent to offspring. Second, more offspring are produced than are able to survive; in other words, resources for survival and reproduction are limited. The capacity for reproduction in all organisms outstrips the availability of resources to support their numbers. Thus, there is a competition for those resources in each generation. Both Darwin and Wallace’s understanding of this principle came from reading an essay by the economist Thomas Malthus, who discussed this principle in relation to human populations. Third, offspring vary among each other in regard to their characteristics and those variations are inherited. Out of these three principles, Darwin and Wallace reasoned that offspring with inherited characteristics that allow them to best compete for limited resources will survive and have more offspring than those individuals with variations that are less able to compete. Because characteristics are inherited, these traits will be better represented in the next generation. This will lead to change in populations over generations in a process that Darwin called “descent with modification.”

Papers by Darwin and Wallace (Figure 11.3) presenting the idea of natural selection were read together in 1858 before the Linnaean Society in London. The following year Darwin’s book, On the Origin of Species, was published, which outlined in considerable detail his arguments for evolution by natural selection.

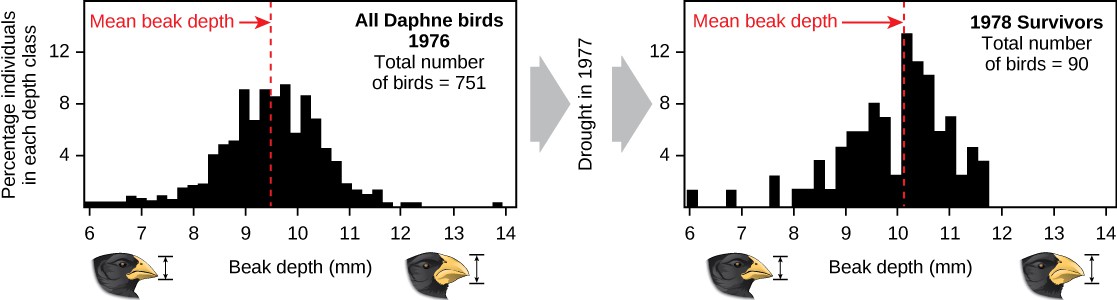

Demonstrations of evolution by natural selection can be time consuming. One of the best demonstrations has been in the very birds that helped to inspire the theory, the Galápagos finches. Peter and Rosemary Grant and their colleagues have studied Galápagos finch populations every year since 1976 and have provided important demonstrations of the operation of natural selection. The Grants found changes from one generation to the next in the beak shapes of the medium ground finches on the Galápagos island of Daphne Major. The medium ground finch feeds on seeds. The birds have inherited variation in the bill shape with some individuals having wide, deep bills and others having thinner bills. Large-billed birds feed more efficiently on large, hard seeds, whereas smaller billed birds feed more efficiently on small, soft seeds. During 1977, a drought period altered vegetation on the island. After this period, the number of seeds declined dramatically: the decline in small, soft seeds was greater than the decline in large, hard seeds. The large-billed birds were able to survive better than the small-billed birds the following year. The year following the drought when the Grants measured beak sizes in the much-reduced population, they found that the average bill size was larger (Figure 11.4). This was clear evidence for natural selection (differences in survival) of bill size caused by the availability of seeds. The Grants had studied the inheritance of bill sizes and knew that the surviving large-billed birds would tend to produce offspring with larger bills, so the selection would lead to evolution of bill size. Subsequent studies by the Grants have demonstrated selection on and evolution of bill size in this species in response to changing conditions on the island. The evolution has occurred both to larger bills, as in this case, and to smaller bills when large seeds became rare.

Variation and Adaptation

Natural selection can only take place if there is variation, or differences, among individuals in a population. Importantly, these differences must have some genetic basis; otherwise, selection will not lead to change in the next generation. This is critical because variation among individuals can be caused by non-genetic reasons, such as an individual being taller because of better nutrition rather than different genes.

Genetic diversity in a population comes from two main sources: mutation and sexual reproduction. Mutation, a change in DNA, is the ultimate source of new alleles or new genetic variation in any population. An individual that has a mutated gene might have a different trait than other individuals in the population. However, this is not always the case. A mutation can have one of three outcomes on the organisms’ appearance (or phenotype):

- A mutation may affect the phenotype of the organism in a way that gives it reduced fitness—lower likelihood of survival, resulting in fewer offspring.

- A mutation may produce a phenotype with a beneficial effect on fitness.

- Many mutations, called neutral mutations, will have no effect on fitness.

Mutations may also have a whole range of effect sizes on the fitness of the organism that expresses them in their phenotype, from a small effect to a great effect. Sexual reproduction and crossing over in meiosis also lead to genetic diversity: when two parents reproduce, unique combinations of alleles assemble to produce unique genotypes and, thus, phenotypes in each of the offspring.

A heritable trait that aids the survival and reproduction of an organism in its present environment is called an adaptation. An adaptation is a “match” of the organism to the environment. Adaptation to an environment comes about when a change in the range of genetic variation occurs over time that increases or maintains the match of the population with its environment. The variations in finch beaks shifted from generation to generation providing adaptation to food availability.

Whether or not a trait is favorable depends on the environment at the time. The same traits do not always have the same relative benefit or disadvantage because environmental conditions can change. For example, finches with large bills were benefited in one climate, while small bills were a disadvantage; in a different climate, the relationship reversed.

Patterns of Evolution

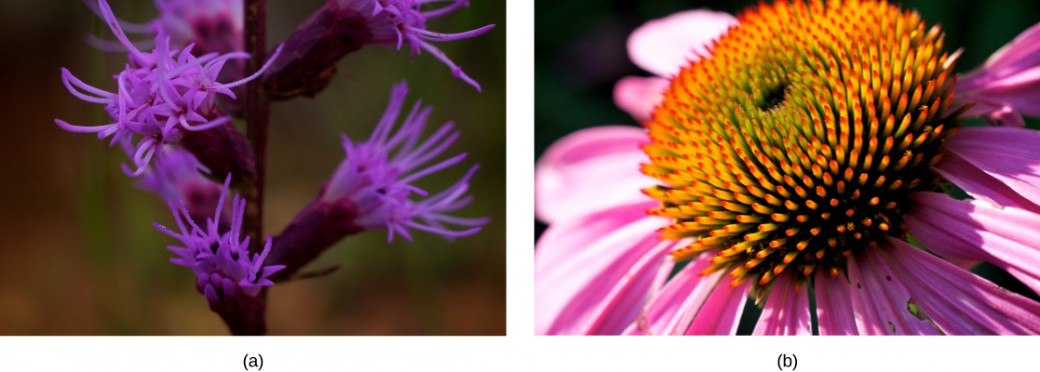

The evolution of species has resulted in enormous variation in form and function. When two species evolve in different directions from a common point, it is called divergent evolution. Such divergent evolution can be seen in the forms of the reproductive organs of flowering plants, which share the same basic anatomies; however, they can look very different as a result of selection in different physical environments, and adaptation to different kinds of pollinators (Figure 11.5).

In other cases, similar phenotypes evolve independently in distantly related species. For example, flight has evolved in both bats and insects, and they both have structures we refer to as wings, which are adaptations to flight. The wings of bats and insects, however, evolved from very different original structures. When similar structures arise through evolution independently in different species it is called convergent evolution. The wings of bats and insects are called analogous structures; they are similar in function and appearance, but do not share an origin in a common ancestor. Instead they evolved independently in the two lineages. The wings of a hummingbird and an ostrich are homologous structures, meaning they share similarities (despite their differences resulting from evolutionary divergence). The wings of hummingbirds and ostriches did not evolve independently in the hummingbird lineage and the ostrich lineage—they descended from a common ancestor with wings.

The Modern Synthesis

The mechanisms of inheritance, genetics, were not understood at the time Darwin and Wallace were developing their idea of natural selection. This lack of understanding was a stumbling block to comprehending many aspects of evolution. In fact, blending inheritance was the predominant (and incorrect) genetic theory of the time, which made it difficult to understand how natural selection might operate. Darwin and Wallace were unaware of the genetics work by Austrian monk Gregor Mendel, which was published in 1866, not long after publication of On the Origin of Species. Mendel’s work was rediscovered in the early twentieth century at which time geneticists were rapidly coming to an understanding of the basics of inheritance. Initially, the newly discovered particulate nature of genes made it difficult for biologists to understand how gradual evolution could occur. But over the next few decades genetics and evolution were integrated in what became known as the modern synthesis—the coherent understanding of the relationship between natural selection and genetics that took shape by the 1940s and is generally accepted today. In sum, the modern synthesis describes how evolutionary pressures, such as natural selection, can affect a population’s genetic makeup, and, in turn, how this can result in the gradual evolution of populations and species. The theory also connects this gradual change of a population over time, called microevolution, with the processes that gave rise to new species and higher taxonomic groups with widely divergent characters, called macroevolution.

Population Genetics

Recall that a gene for a particular character may have several variants, or alleles, that code for different traits associated with that character. For example, in the ABO blood type system in humans, three alleles determine the particular blood-type protein on the surface of red blood cells. Each individual in a population of diploid organisms can only carry two alleles for a particular gene, but more than two may be present in the individuals that make up the population. Mendel followed alleles as they were inherited from parent to offspring. In the early twentieth century, biologists began to study what happens to all the alleles in a population in a field of study known as population genetics.

Until now, we have defined evolution as a change in the characteristics of a population of organisms, but behind that phenotypic change is genetic change. In population genetic terms, evolution is defined as a change in the frequency of an allele in a population. Using the ABO system as an example, the frequency of one of the alleles, IA, is the number of copies of that allele divided by all the copies of the ABO gene in the population. For example, a study in Jordan found a frequency of IA to be 26.1 percent.2 The IB, I0 alleles made up 13.4 percent and 60.5 percent of the alleles respectively, and all of the frequencies add up to 100 percent. A change in this frequency over time would constitute evolution in the population.

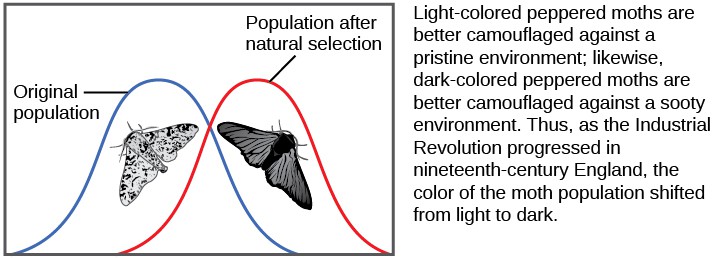

There are several ways the allele frequencies of a population can change. One of those ways is natural selection. If a given allele confers a phenotype that allows an individual to have more offspring that survive and reproduce, that allele, by virtue of being inherited by those offspring, will be in greater frequency in the next generation. Since allele frequencies always add up to 100 percent, an increase in the frequency of one allele always means a corresponding decrease in one or more of the other alleles. Highly beneficial alleles may, over a very few generations, become “fixed” in this way, meaning that every individual of the population will carry the allele. Similarly, detrimental alleles may be swiftly eliminated from the gene pool, the sum of all the alleles in a population. Part of the study of population genetics is tracking how selective forces change the allele frequencies in a population over time, which can give scientists clues regarding the selective forces that may be operating on a given population. The studies of changes in wing coloration in the peppered moth from mottled white to dark in response to soot-covered tree trunks and then back to mottled white when factories stopped producing so much soot is a classic example of studying evolution in natural populations (Figure 11.6).

In the early twentieth century, English mathematician Godfrey Hardy and German physician Wilhelm Weinberg independently provided an explanation for a somewhat counterintuitive concept. Hardy’s original explanation was in response to a misunderstanding as to why a “dominant” allele, one that masks a recessive allele, should not increase in frequency in a population until it eliminated all the other alleles. The question resulted from a common confusion about what “dominant” means, but it forced Hardy, who was not even a biologist, to point out that if there are no factors that affect an allele frequency those frequencies will remain constant from one generation to the next. This principle is now known as the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The theory states that a population’s allele and genotype frequencies are inherently stable—unless some kind of evolutionary force is acting on the population, the population would carry the same alleles in the same proportions generation after generation. Individuals would, as a whole, look essentially the same and this would be unrelated to whether the alleles were dominant or recessive. The four most important evolutionary forces, which will disrupt the equilibrium, are natural selection, mutation, genetic drift, and migration into or out of a population. A fifth factor, nonrandom mating, will also disrupt the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium but only by shifting genotype frequencies, not allele frequencies. In nonrandom mating, individuals are more likely to mate with like individuals (or unlike individuals) rather than at random. Since nonrandom mating does not change allele frequencies, it does not cause evolution directly. Natural selection has been described. Mutation creates one allele out of another one and changes an allele’s frequency by a small, but continuous amount each generation. Each allele is generated by a low, constant mutation rate that will slowly increase the allele’s frequency in a population if no other forces act on the allele. If natural selection acts against the allele, it will be removed from the population at a low rate leading to a frequency that results from a balance between selection and mutation. This is one reason that genetic diseases remain in the human population at very low frequencies. If the allele is favored by selection, it will increase in frequency. Genetic drift causes random changes in allele frequencies when populations are small. Genetic drift can often be important in evolution, as discussed in the next section. Finally, if two populations of a species have different allele frequencies, migration of individuals between them will cause frequency changes in both populations. As it happens, there is no population in which one or more of these processes are not operating, so populations are always evolving, and the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium will never be exactly observed. However, the Hardy-Weinberg principle gives scientists a baseline expectation for allele frequencies in a non-evolving population to which they can compare evolving populations and thereby infer what evolutionary forces might be at play. The population is evolving if the frequencies of alleles or genotypes deviate from the value expected from the Hardy-Weinberg principle.

Darwin identified a special case of natural selection that he called sexual selection. Sexual selection affects an individual’s ability to mate and thus produce offspring, and it leads to the evolution of dramatic traits that often appear maladaptive in terms of survival but persist because they give their owners greater reproductive success. Sexual selection occurs in two ways: through male–male competition for mates and through female selection of mates. Male–male competition takes the form of conflicts between males, which are often ritualized, but may also pose significant threats to a male’s survival. Sometimes the competition is for territory, with females more likely to mate with males with higher quality territories. Female choice occurs when females choose a male based on a particular trait, such as feather colors, the performance of a mating dance, or the building of an elaborate structure. In some cases male–male competition and female choice combine in the mating process. In each of these cases, the traits selected for, such as fighting ability or feather color and length, become enhanced in the males. In general, it is thought that sexual selection can proceed to a point at which natural selection against a character’s further enhancement prevents its further evolution because it negatively impacts the male’s ability to survive. For example, colorful feathers or an elaborate display make the male more obvious to predators.

Section Summary

Evolution by natural selection arises from three conditions: individuals within a species vary, some of those variations are heritable, and organisms have more offspring than resources can support. The consequence is that individuals with relatively advantageous variations will be more likely to survive and have higher reproductive rates than those individuals with different traits. The advantageous traits will be passed on to offspring in greater proportion. Thus, the trait will have higher representation in the next and subsequent generations leading to genetic change in the population.

The modern synthesis of evolutionary theory grew out of the reconciliation of Darwin’s, Wallace’s, and Mendel’s thoughts on evolution and heredity. Population genetics is a theoretical framework for describing evolutionary change in populations through the change in allele frequencies. Population genetics defines evolution as a change in allele frequency over generations. In the absence of evolutionary forces allele frequencies will not change in a population; this is known as Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium principle. However, in all populations, mutation, natural selection, genetic drift, and migration act to change allele frequencies.

Glossary

- adaptation: a heritable trait or behavior in an organism that aids in its survival in its present environment

- analogous structure: a structure that is similar because of evolution in response to similar selection pressures resulting in convergent evolution, not similar because of descent from a common ancestor

- convergent evolution: an evolution that results in similar forms on different species

- divergent evolution: an evolution that results in different forms in two species with a common ancestor

- gene pool: all of the alleles carried by all of the individuals in the population

- genetic drift: the effect of chance on a population’s gene pool

- homologous structure: a structure that is similar because of descent from a common ancestor

- inheritance of acquired characteristics: a phrase that describes the mechanism of evolution proposed by Lamarck in which traits acquired by individuals through use or disuse could be passed on to their offspring thus leading to evolutionary change in the population

- macroevolution: a broader scale of evolutionary changes seen over paleontological time

- microevolution: the changes in a population’s genetic structure (i.e., allele frequency)

- migration: the movement of individuals of a population to a new location; in population genetics it refers to the movement of individuals and their alleles from one population to another, potentially changing allele frequencies in both the old and the new population

- modern synthesis: the overarching evolutionary paradigm that took shape by the 1940s and is generally accepted today

- natural selection: the greater relative survival and reproduction of individuals in a population that have favorable heritable traits, leading to evolutionary change

- population genetics: the study of how selective forces change the allele frequencies in a population over time

- variation: the variety of alleles in a population

Footnotes

- 1 Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N, 2nd. ed. (London: John Murray, 1860), http://www.archive.org/details/journalofresea00darw.

- 2 Sahar S. Hanania, Dhia S. Hassawi, and Nidal M. Irshaid, “Allele Frequency and Molecular Genotypes of ABO Blood Group System in a Jordanian Population,” Journal of Medical Sciences 7 (2007): 51-58, doi:10.3923/jms.2007.51.58

Media Attributions

- Figure 11.2 © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 11.3 © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 11.4 © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 11.5 © Modification of work by Cory Zanker; OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 11.6 © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license