White Blood Cells

Objective 4

Define leukocyte, and identify the various types of white blood cells normally present in the blood. Describe the basic functions of the individual white blood cells and be able to identify them from their microscopic appearance on a blood smear.

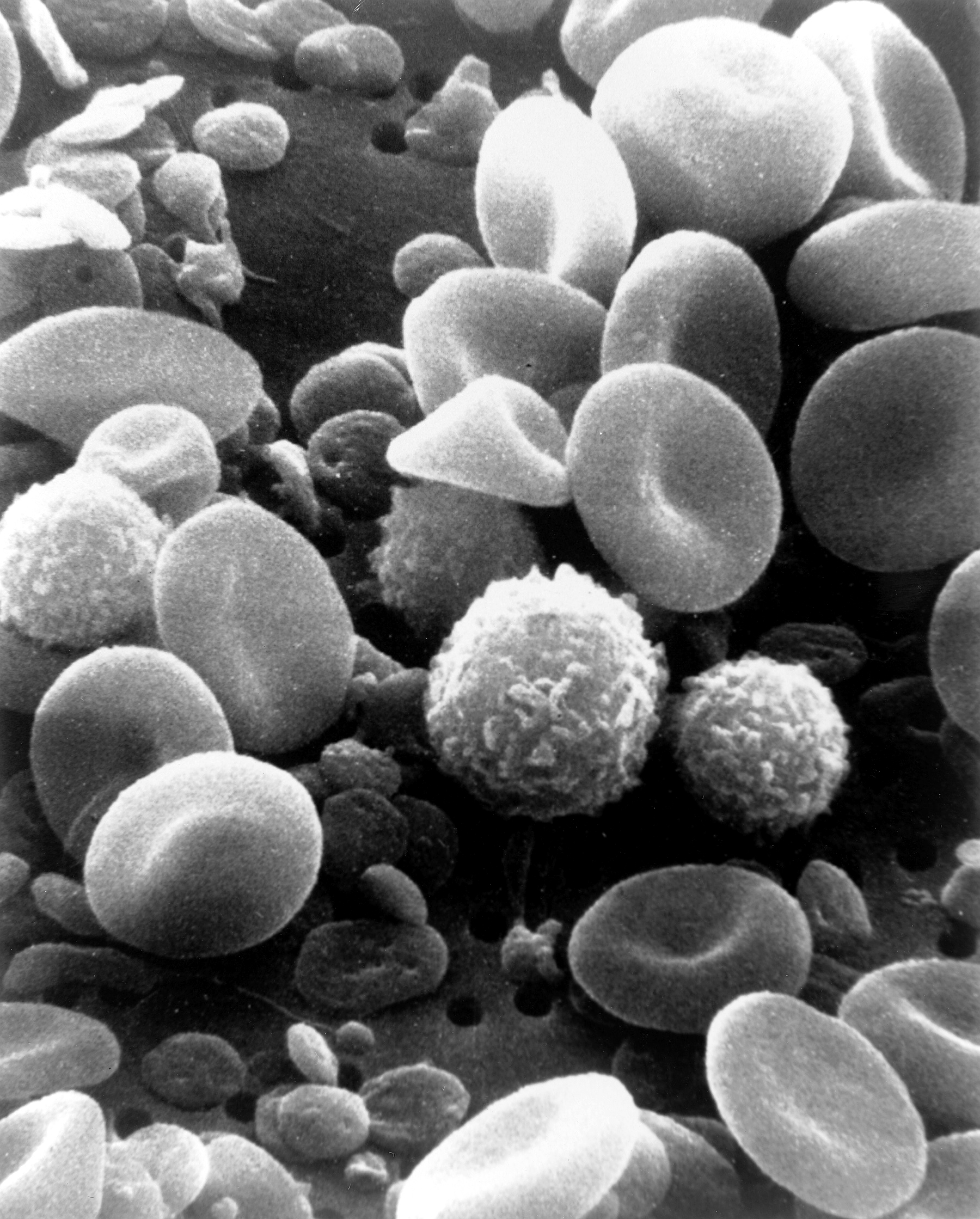

Leukocyte is another term for a white blood cell. White blood cells (WBCs) are very different from red blood cells: they have nuclei, they are larger, they don’t have hemoglobin, and there are different types with unique functions. There are much fewer white blood cells circulating in the blood stream than red blood cells. A normal white blood cell count is 5.0-10.0 x 103 WBCs/µL. White blood cells are formed in the red bone marrow and are released to other lymphatic organs to mature and become activated. Activated white blood cells perform a number of functions, including engulfing pathogens (phagocytosis), destroying dangerous cells, releasing antibodies, sending out chemical messages, encouraging inflammation, and coordinating responses with other body systems.

Leukocyte is another term for a white blood cell. White blood cells (WBCs) are very different from red blood cells: they have nuclei, they are larger, they don’t have hemoglobin, and there are different types with unique functions. There are much fewer white blood cells circulating in the blood stream than red blood cells. A normal white blood cell count is 5.0-10.0 x 103 WBCs/µL. White blood cells are formed in the red bone marrow and are released to other lymphatic organs to mature and become activated. Activated white blood cells perform a number of functions, including engulfing pathogens (phagocytosis), destroying dangerous cells, releasing antibodies, sending out chemical messages, encouraging inflammation, and coordinating responses with other body systems.

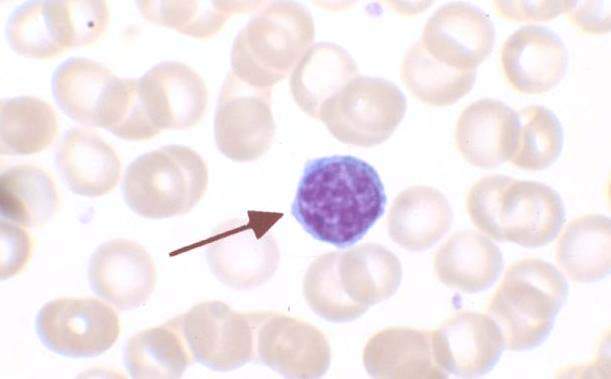

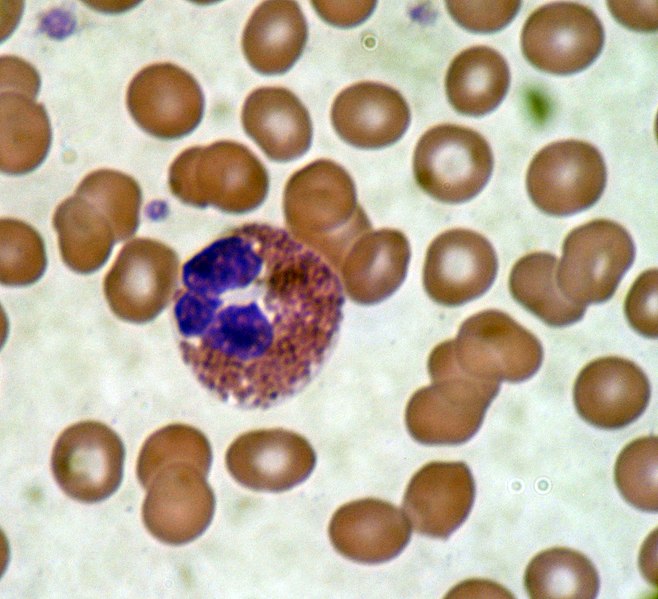

WBCs can be separated into two groups based on the presence of cytoplasmic granules. They are the granulocytes (granular leukocytes) and the agranulocytes (agranular leukocytes). These granules are visible under a microscope when the cells are stained.

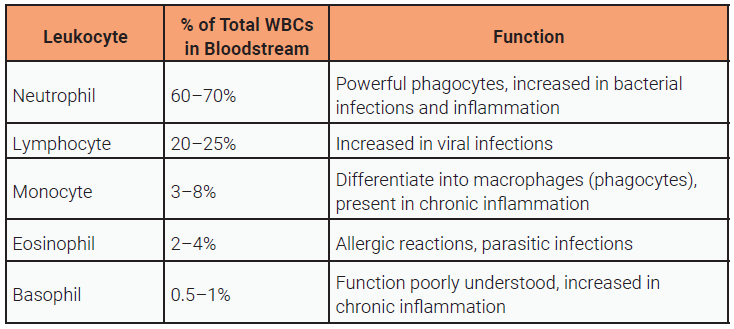

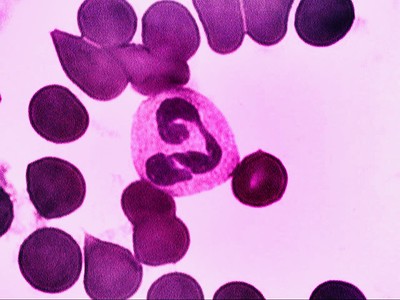

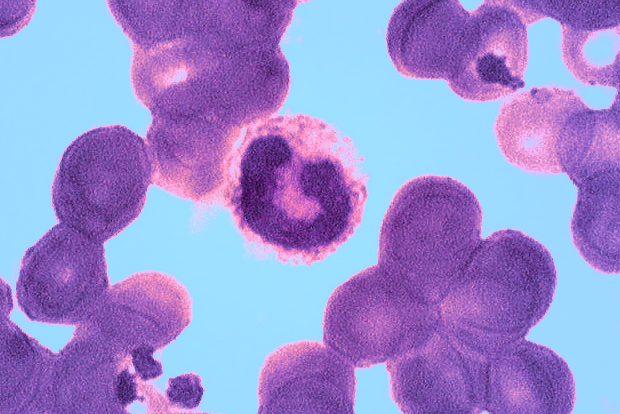

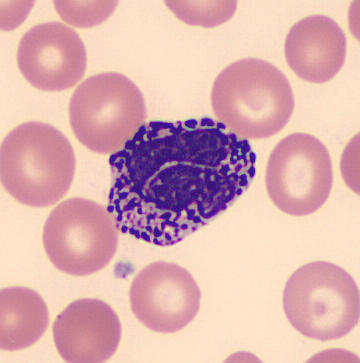

The granulocytic group includes three specific types of WBCs: neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils. The names of these cells come from their staining characteristics. The granules of an eosinophil stain red with an (acidic) eosin stain. The granules of a basophil stain dark purple with a (basic) hematoxylin stain, and the granules of a neutrophils stain somewhere in the middle, ending up a purple to pinkish color.

The agranulocytes do contain some cytoplasmic granules but they are much less prominent and they don’t stain as well as their granulocytic counterparts. Lymphocytes and monocytes are included in this group. Monocytes exist as such only as they move from the bone marrow, through the circulation and then into the tissues. In the tissues they become macrophages and dendritic cells, which have important functions like phagocytosis and antigen presentation.

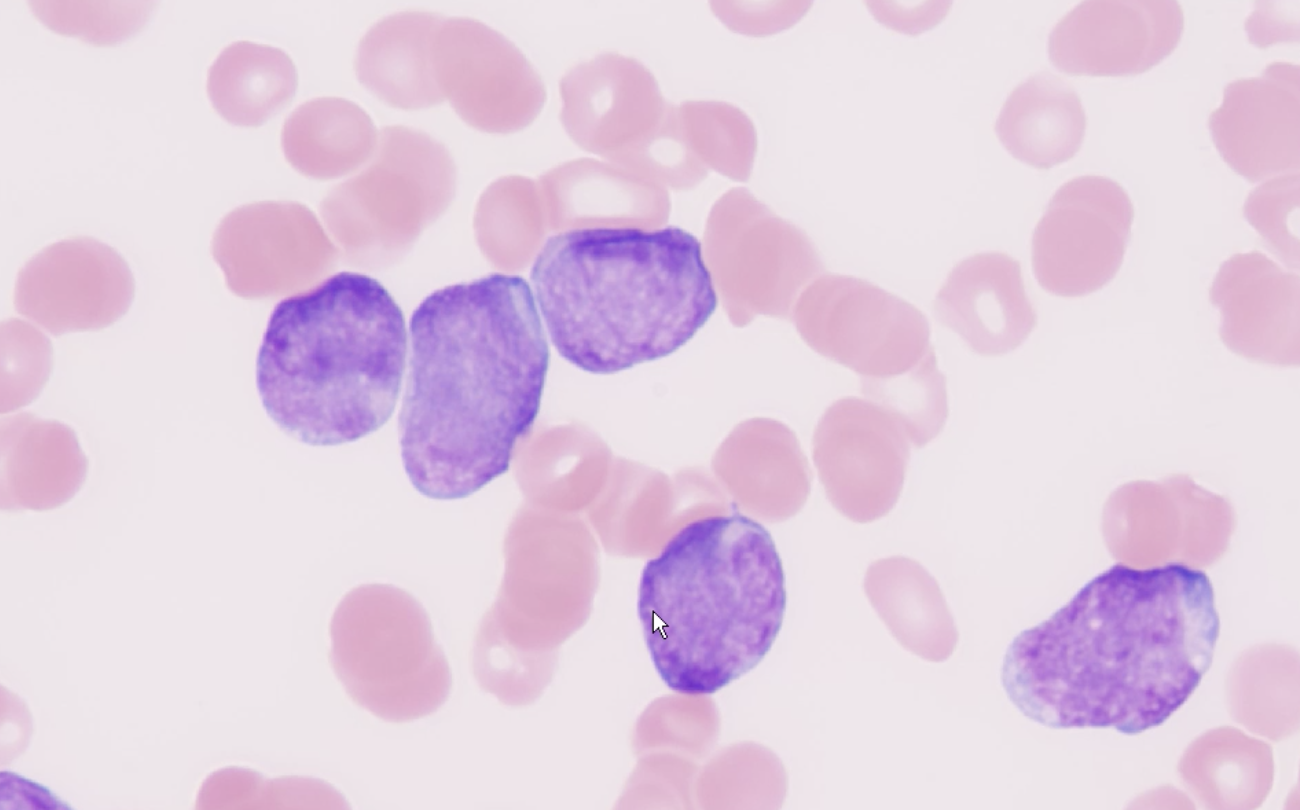

Leukocytosis is an increase in the number of white blood cells. Leukocytosis is a normal physiologic response to a number of conditions, including infection, inflammation, and other forms of physiologic stress. White blood cell counts can approach 30 X 103 WBC/µL in these conditions. When the number of white blood cells exceed this, it is typically indicative of a problem with the bone marrow itself, a condition most often classified as leukemia. It is never normal to have lower than 5 X 103 WBC/µL. This condition, called leukopenia, can result from AIDS, chemotherapy, autoimmune disorders and bone marrow failure.

White blood cells provide a powerful protection against microorganisms and other injurious agents. Each, based on its structure, has unique functional possibilities.

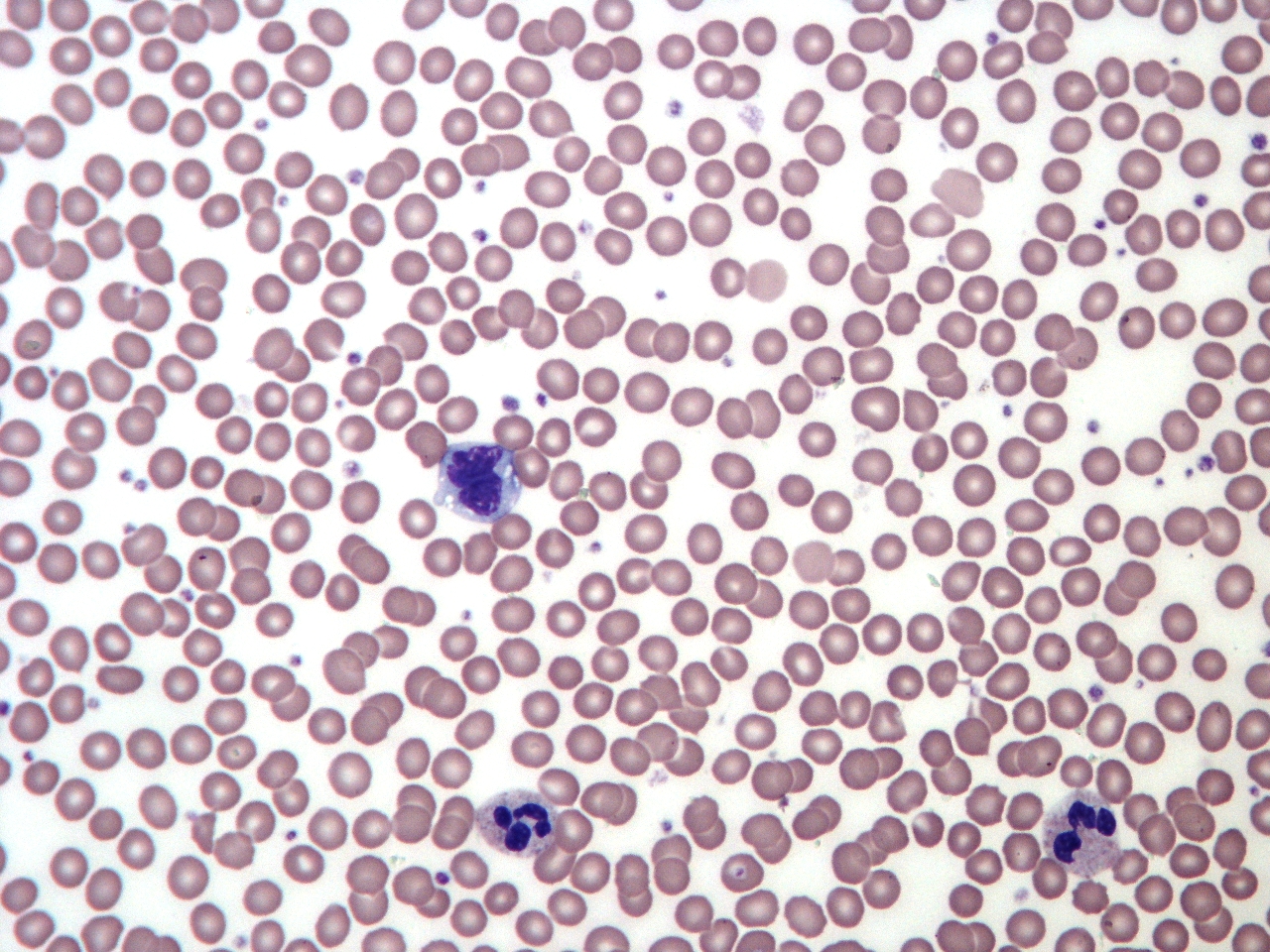

When a patient has an increased white blood cell count, a physician will frequently order a white blood cell differential analysis which indicates the percentage of each type of white cell in the blood. This provides information about the patient’s condition. For example, if an individual has an increased number of white blood cells and the overall percentage of neutrophils is increased, it is likely that they have a bacterial infection. If lymphocytes are higher than normal, it is likely the patient has a viral infection. Red blood cell characteristics are also noted while doing a differential, therefore they are very useful in diagnosing and monitoring disorders like anemia, leukemia, and AIDS.

Media Attributions

- U15-015 SEM Blood Cells © Wetzel, Bruce and Schaefer, Harry is licensed under a Public Domain license

- U15-016 Leukemia © Uthman, Ed MD is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- U15-017 Normal Differential © Chambers, Keith is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U15-018 WBC Table © Price, Travis and Newton, Kathy is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U15-019 Neutrophil © Wiklund, Magdalena is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

- U15-020 Band Neutrophil © Wiklund, Magdalena is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

- U15-021a Lymphocyte © isis325 is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- U15-021b Monocytes © Beards, Graham Dr. is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U15-023 Basophil © El*Falaf is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U15-022 Eosinophil Blood Smear © Bobjgalindo is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license