Hematopoiesis

Objective 2

Define and describe hematopoiesis and erythropoiesis.

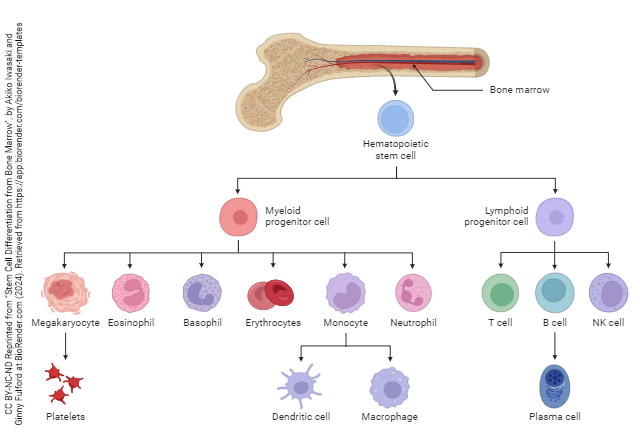

Hematopoiesis (hemato–, blood; –poiesis, making) is the formation of the formed elements of the blood. All blood cells begin as pluripotent stem cells in the red bone marrow. These stem cells can be influenced by the body to differentiate into any of the mature blood cells.

In infants, all of the bones contain red bone marrow and are actively making formed elements. As an individual matures, the red bone marrow in the long bones is replaced with yellow bone marrow, which is mostly adipose tissue. In adults, the remaining active red marrow is found most often in the spongy portion of the bones of the axial skeleton.

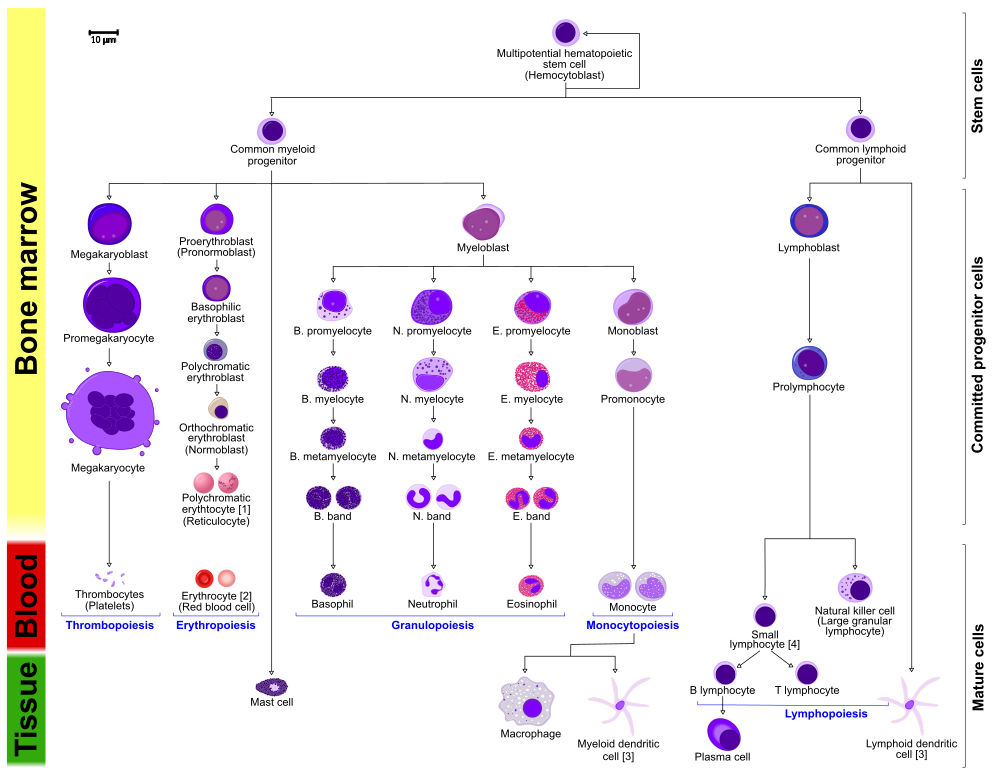

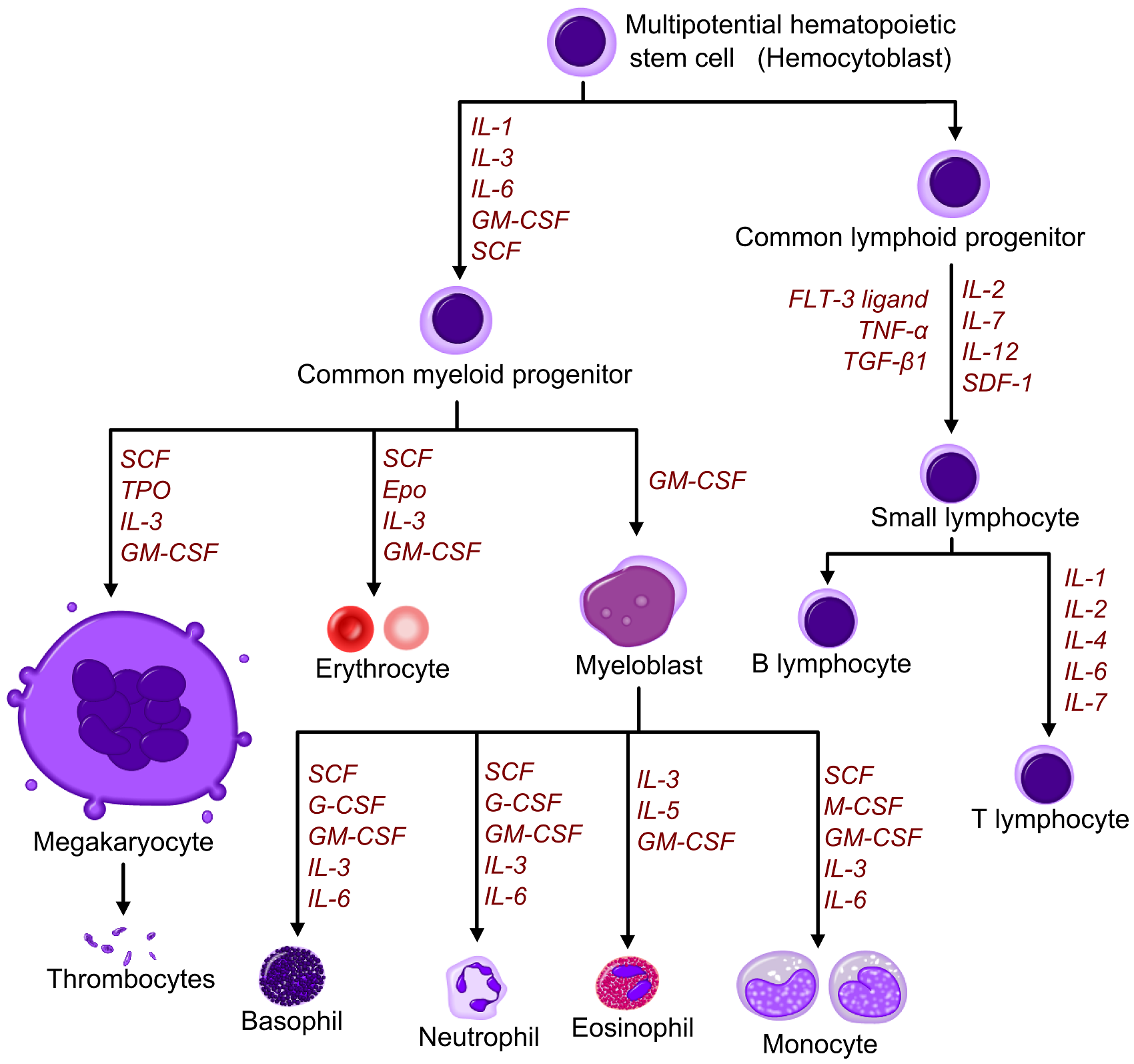

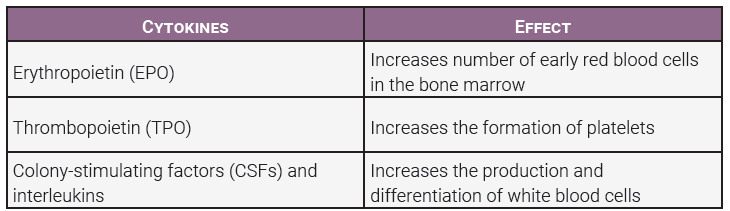

Proliferation and maturation of blood cells depends on specific cytokines, chemical signals from one group of cells that stimulate another. Under the influence of these signals (growth factors, colony-stimulating factors, and interleukins), cells differentiate into the various cell types. The stem cells differentiate into either the myeloid group or the lymphoid group. The names indicate where the cells are formed and mature.

The immature myeloid (bone marrow) cells differentiate and become red blood cells, platelets, and many types of white blood cells. The lymphoid cells mature in the lymphatic system and give rise to a specific group of white blood cells called lymphocytes. This graphic adds specific cytokines needed for cellular differentiation. The chart below the diagram gives specific cytokines you are required to learn.

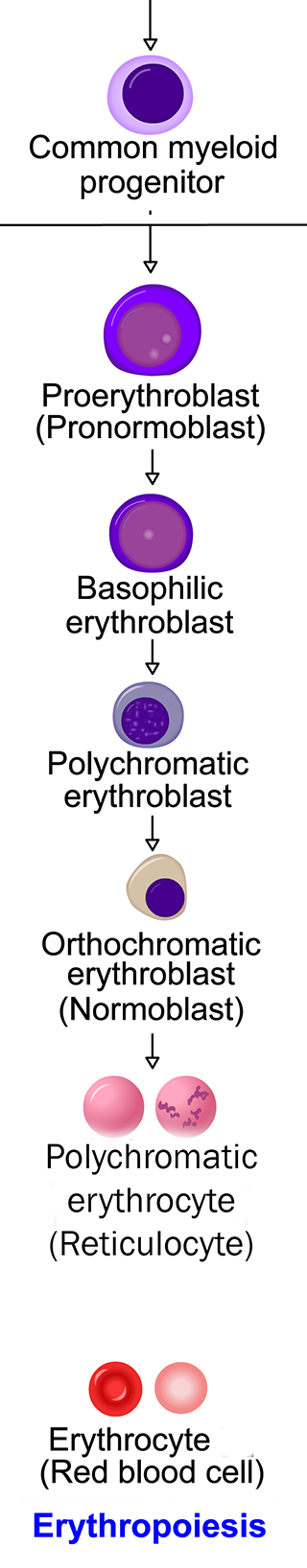

Erythropoiesis is part of hematopoiesis, specifically relating to the production and maturation of red blood cells. Red blood cells are produced continuously (approximately 2 million per second) to keep up with normal death and destruction of the cells.

Erythropoiesis is part of hematopoiesis, specifically relating to the production and maturation of red blood cells. Red blood cells are produced continuously (approximately 2 million per second) to keep up with normal death and destruction of the cells.

The average person has 4.00-6.00 x 106 RBC/µL of blood. If the number of red blood cells lost exceeds the number made, hypoxemia (too little oxygen in the blood) can result. In this case, the lack of oxygen is not due to problems with breathing; there just aren’t enough red blood cells to transport the available oxygen around the body. The decreased amount of oxygen is detected in the kidneys and the kidneys secrete erythropoietin (EPO), a hormone to increase the rate of erythropoiesis. EPO increases the development of red cells in the bone marrow.

Immature red blood cells are large, they have a nucleus, very little cytoplasm, and they lack hemoglobin. As a red cell matures, it becomes smaller, increases its hemoglobin content, and loses its nucleus.

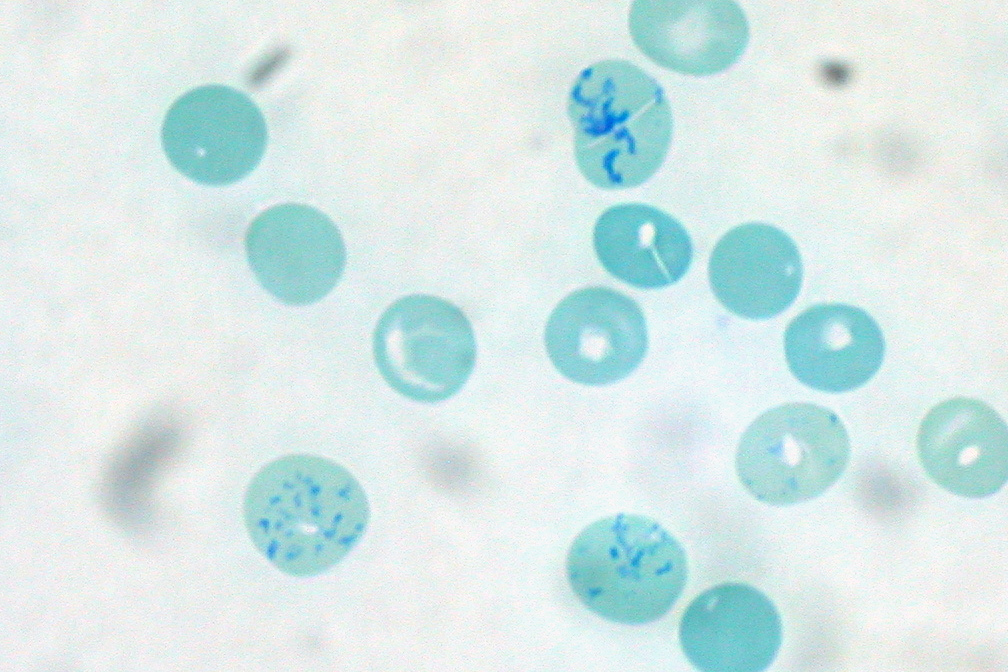

The loss of the nucleus contributes to the red blood cell gaining its biconcave shape, but it isn’t mature yet; it still contains some mitochondria, ribosomes, and endoplasmic reticulum. This almost-mature red cell is called a reticulocyte or polychromatic erythrocyte. These reticulocytes are released into the blood stream and will mature over the next 1-2 days. Normally, 0.5-1.5% of circulating red blood cells are reticulocytes. If the reticulocyte count is higher than normal it indicates an increased rate of red blood cell production, a condition that has many possible causes. There are about 1000 red blood cells for every one white blood cell in the circulation. As a result, the total number of red blood cells is the most significant contributor to a person’s hematocrit.

The number of red blood cells is an important part of maintaining homeostasis throughout the body. A count below 4.00 x 106 RBC/µL may indicate increased destruction of red blood cells, increased fragility of the cells, or decreased production. Generally, conditions of lower than normal red blood cells are referred to as anemia. Overproduction of red blood cells is also possible, resulting in a condition referred to as polycythemia.

The number of red blood cells is an important part of maintaining homeostasis throughout the body. A count below 4.00 x 106 RBC/µL may indicate increased destruction of red blood cells, increased fragility of the cells, or decreased production. Generally, conditions of lower than normal red blood cells are referred to as anemia. Overproduction of red blood cells is also possible, resulting in a condition referred to as polycythemia.

Media Attributions

- U15-003 Stem Cell Differentiation from Bone Marrow © Iwasaki, Akiko and Fulford, Ginny is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- U15-004 Hematopoiesis (human) Diagram © Häggström, Mikael M.D. is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U15-005 Hematopoietic Growth Factors © Häggström, Mikael M.D. is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U15-006 Cytokines and their Effects on Hematopoiesis Table © Price, Travis and Newton, Kathy is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U15-007 Erythropoiesis modified © Häggström, Mikael M.D. adapted by Jim Hutchins is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- U15-008 Reticulocytes © Uthman, Ed MD is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license