Benign Rolandic Epilepsy (BRE)

Kobe Christensen and Jim Hutchins

BENIGN ROLANDIC EPILEPSY (BRE)

Introduction

Benign Rolandic Epilepsy (BRE) is a common childhood epilepsy syndrome presenting with infrequent focal motor seizures that typically resolve before the age of 13 (hence “Benign”). Another commonly used name for BRE is Benign Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes (BECTS). Seizures originate centrotemporally from the Rolandic area of the brain (other names for the Rolandic fissure are the central fissure and most commonly the central sulcus).

“Central Sulcus Diagram” by jimhutchins. “Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0” CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Figure 4.1 showing the central sulcus (Rolandic fissure) which is the area is affected by BRE.

Symptoms

Seizures

Benign Rolandic Epilepsy is characterized by focal motor seizures. These focal motor seizures frequently effect the oropharynx and thus hypersalivation, anarthria, and a facial droop are common clinical symptoms seen during these seizures. Seizures in BRE usually occur at night or shortly after waking and thus an EEG during sleep is preferred. Rarely a Jacksonian march up to generalized tonic-clonic and even status epilepticus will be seen.

Onset of seizures typically occurs between the ages of 3 and 13 years old with the mean onset being at 7 years old. The majority of patients with BRE enter remission by age 13. Most children have less than 10 total seizures before the disorder spontaneously resolves.

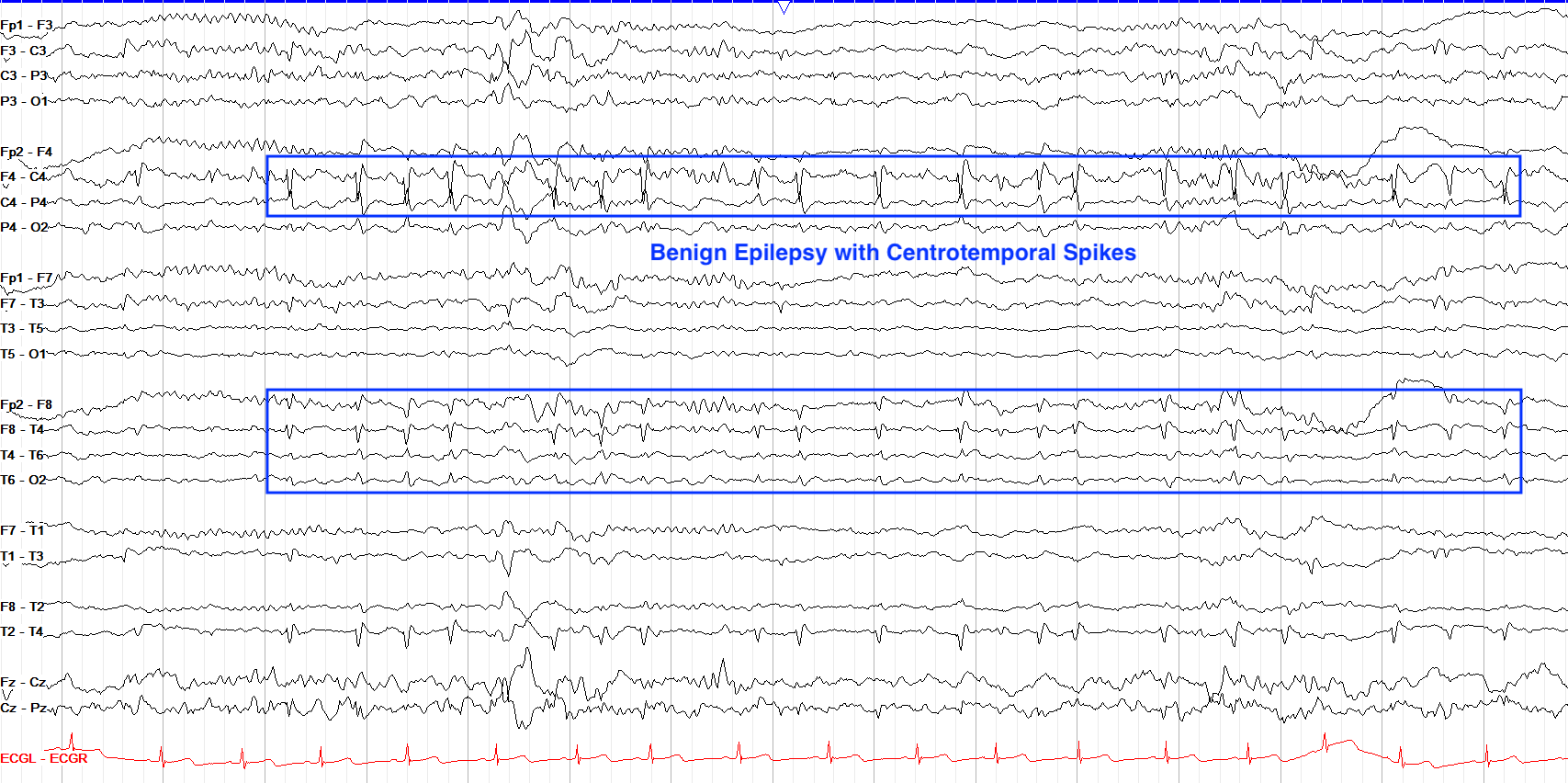

EEG

EEG in BRE will show high amplitude biphasic spike and slow wave complexes seen maximally in centrotemporal areas. Epileptiform in BRE is best seen during sleep.

From “The Pediatric EEG”, by David Valentine M.D., 2020, (https://www.learningeeg.com/pediatric). Copyright 2020 by David Valentine

Figure 4.2 Showing centrotemporal spike and wave complexes in a patient with BRE.

Treatment & Prognosis

Prognosis

Prognosis for BRE is generally good as seizures spontaneously resolve in the majority of patients. Occasionally there are minor cognitive and behavioral abnormalities associated with higher frequency of seizures in BRE, but typically patients have less than less than 10 total seizures. Rarely, seizures persist into adulthood.

Treatment

Because BRE tends to spontaneously resolve, treatment with AEDs is rarely recommended. Frequent seizures occurring during the day time and the progression of focal motor seizures to GTC’s are an indication for the use of AEDs. In these cases, Carbamazepine tends to be the front line medication used.

Key Takeaways

- Benign Rolandic Epilepsy is characterized by focal-motor aware seizures originating from the centrotemporal region of the brain.

- Benign Rolandic Epilepsy has a characteristic centrotemporal spike pattern seen on EEG.

- The majority of children have less than 10 total seizures, before spontaneously resolving.

LENNOX-GASTAUT SYNDROME

Introduction

Lennox-Gastaut (LGS) is an uncommon pediatric epilepsy syndrome that makes up around 10% of childhood epilepsy. Lennox-Gastaut is characterized by the onset of multiple different seizure types, severe cognitive delay, and a distinct EEG pattern.

History

Lennox-Gastaut is named after the two physicians who first documented the disease. In the 1950's, Dr. William Lennox described a particular EEG finding that would match an epilepsy syndrome that Dr. Henri Gastaut was studying in the mid 1960's. Dr. Henri Gastaut described a childhood epilepsy with frequent tonic and absence seizures. Later it was found that both Dr. Lennox and Dr. Gastaut were studying the same epilepsy syndrome and thus it was coined Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

Symptoms

Lennox-Gastaut is frequently associated with intractable epilepsy, severe cognitive impairment, and characteristic EEG.

Epilepsy

Patients with Lennox-Gastaut tend to present with multiple seizure types.

- Tonic

- Tonic-Clonic

- Atonic (Drop attacks)

- Myoclonic

- Atypical Absence (With characteristic EEG pattern)

Seizures in patients with Lennox-Gastaut are frequent in nature and tend to cluster making them at high risk for evolving into Non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) with some studies showing an incidence of NCSE being over 50%.

The average of seizure onset in patients with LGS is between 3-5 years of age. Almost all patients with an LGS diagnosis have an onset of seizures before 8 years of age.

Cognitive Impairment

Cognitive impairment before seizure onset is seen in roughly 40% of patients. Depending on the severity of the disease there may be a delayed onset of cognitive delay after the patient has their first seizure.

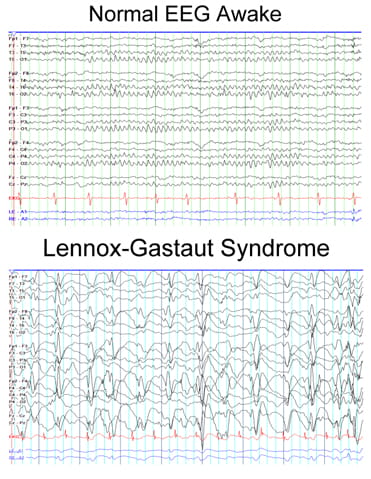

Characteristic EEG pattern

EEG in patients with LGS can be complex and difficult to read. Due to the multitude of seizure types, LGS seizure can present in several different ways which may make it difficult to differentiate the disease from others. However, in LGS there is a very characteristic EEG pattern known as atypical absence which helps to set it apart from others.

Atypical absence seizures are defined as slow (1.5-2.5 Hz) irregular polyspike and wave activity. It is important to note that atypical absence seizures differ from typical absence seizures in that they are slower (Typical absence seizures tend to be in the 3-5 Hz range) and are often asymmetric (Typical absence seizures are almost always generalized). Atypical absence seizures are NOT triggered by hyperventilation.

<a title="Lennox-Gastaut, BY UPMC

UPMC "Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome"

Figure 2.1 showing Atypical Absence seizure with characteristic 1.5-2.5 Hz slow waves with asymmetrical polyspike discharges.

Other patterns that can be seen in Ictal EEG of an LGS patient include:

- Rhythmic, high amplitude discharges in the high alpha-beta ranges seen in tonic seizures.

- Arrhythmic bursts of polyspike-wave discharges seen in myoclonic seizures.

Classifications of disease

LGS diagnoses typically fall into the following two categories: Secondary & Idiopathic

Secondary LGS:

This accounts for about 75% of all cases and describes a known primary cause. Any damage to the brain before or during birth can be considered a primary cause to LGS. These include:

- Infection

- Frontal lobe injury

- Tuberous Sclerosis

- Perinatal asphyxia

- Perinatal stroke

- Abnormal development

Idiopathic LGS

These account for the other 25% of LGS cases and have no known cause.

Linkage between Lennox-Gastaut & West Syndrome

An LGS diagnosis has been to known to frequently follow a myriad of other childhood epilepsy diagnoses. None are more common than the diagnosis of West Syndrome. Up to 30% of known LGS cases follow a diagnosis of West Syndrome despite no known cause for the linkage of the two.

Treatments & Prognosis

Long-term prognosis is generally unfavorable for patients with LGS. While mortality secondary to LGS is low sitting around ~3 %, severe cognitive impairment and treatment resistant epilepsy still persists in the majority of patients. Patients with a history of West Syndrome also tend to have worse outcomes than those with idiopathic LGS.

Treatment options in LGS vary due to the multitude of seizure types. Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) tend to be the mainline treatment for LGS but rarely does a single AED give complete relief of seizures. Valproic Acid and Lamotrigine are the most commonly used AEDs in LGS. Other forms of treatment include the Ketogenic Diet, VNS, and surgical intervention. LGS patients are good candidates for corpus callostomy to help reduce the frequency of seizures, though it is rare for surgical intervention to be completely curative.

Key Takeaways

- 1.5-2.5 Hz Absence seizures are a common EEG finding in patients with LGS.

- LGS is likely to be secondary to some form of neurological damage before or during birth.

- There is a common progression of West Syndrome to Lennox-Gastaut.

- Valproic acid is the mainline treatment for LGS, followed by a variety of other AEDs as needed.