Sturge-Weber Syndrome

Kobe Christensen and Jim Hutchins

STURGE-WEBER SYNDROME

Introduction

Sturge-Weber Syndrome (SWS) is a neurocutaneous disorder caused by a mutation of the GNAQ gene located on the long arm of chromosome 9. In SWS angiomas of the leptomeninges, trigeminal nerve, and skin of the face are seen. SWS presents with seizures that generally begin as focal seizures and often progress to generalized seizures. The hallmark of SWS is a unilateral vascular lesion called the Port-Wine stain.

Babaji P, Bansal A, Choudhury GK, Nayak R, Kodangala Prabhakar A, Suratkal N, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3.1 showing an 8 year old female with Sturge-Weber Syndrome with characteristic Port-Wine stain.

Signs & Symptoms

Sturge-Weber Syndrome is characterized by refractory epilepsy, neurological deficits, and physical signs of angioma.

Epilepsy

The majority of SWS patients will experience seizures within the first year of life. These seizures are described as infantile spasms and are similar to those described in children with West Syndrome. Seizures that are initially focal in nature tend to progress to generalized seizures of different types. Seizures in SWS can present as atonic, tonic, and myoclonic seizures with the incidence of absence seizures being less frequent.

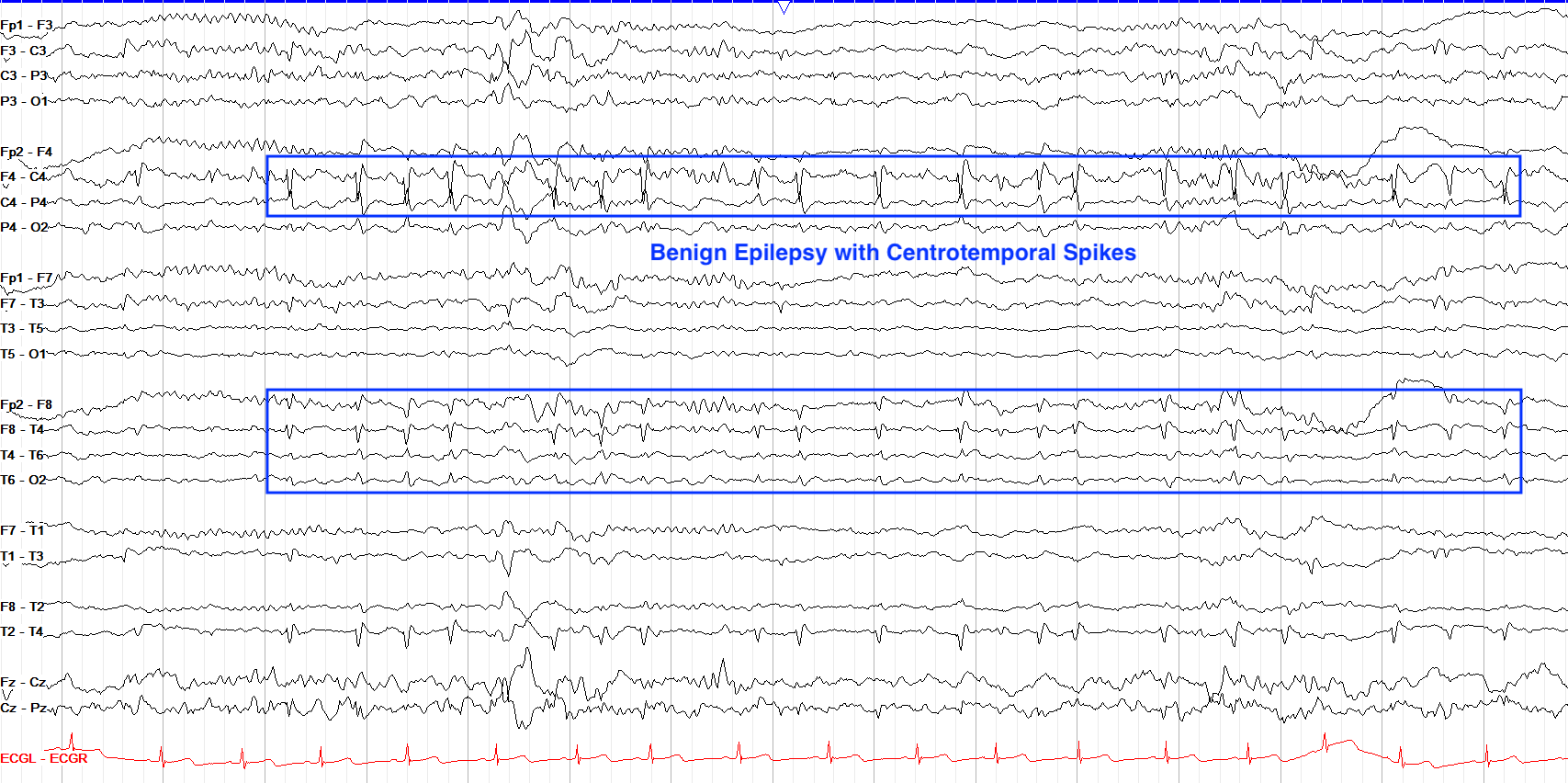

EEG in Sturge-Weber Syndrome generally shows asymmetry of the hemispheres with there being an increased frequency of epileptiform activity on the ipsilateral side to the Port-Wine stain. This epileptiform typically presents as focal spike and wave discharges that can evolve to rhythmic generalized spike and wave.

Neurological Deficit

The extent of neurological deficit associated with SWS can greatly vary from patient to patient. Some patients with SWS show mild behavioral problems, while others have severe cognitive impairment. It is believed that there is a link between seizure frequency and cognitive impairment, however this has yet to be confirmed.

Another determining factor in the degree of neurological deficit is tied to the extent of brain malformation. In 85% of SWS cases, the leptomeningeal angiomas are unilateral and tend to have less severe clinical symptoms in comparison to leptomeningeal angiomas that are seen bilaterally.

Physical Signs

The hallmark of SWS is the Port-Wine stain, but patients with SWS can have several other telling clinical symptoms. Many ocular related conditions are associated with SWS including glaucoma, hemianopsia, and total vision loss. Other signs of SWS can be the development of hemiparesis ipsilateral to the Port-Wine stain, migraines, and weakness.

Treatment & Prognosis

Outcomes for SWS vary based on type of SWS, progression of bilateral leptomeningeal angiomas, severity of seizures etc. It is common for patients to continue to have refractory seizures after AED treatment and subsequent furtherment of cognitive impairment.

Medications used to treat focal seizures are the mainline treatments for epilepsy in SWS. The most common medications used are oxcarbazepine in addition to levetiracetam. Surgery is an option for patients with SWS depending on severity of seizures, location in relation to the leptomeningeal angioma, and location of seizure onset.

Key Takeaways

- Sturge-Weber Syndrome is a neurocutaneous disorder associated with the Port-Wine stain.

- Infantile spasms are common in SWS. Tuberous sclerosis caused by SWS can be the main cause for West Syndrome.

- Ocular related conditions like glaucoma and hemianopsia are related to SWS and are typically seen in the ipsilateral eye to the Port-Wine stain.

BENIGN ROLANDIC EPILEPSY (BRE)

Introduction

Benign Rolandic Epilepsy (BRE) is a common childhood epilepsy syndrome presenting with infrequent focal motor seizures that typically resolve before the age of 13 (hence "Benign"). Another commonly used name for BRE is Benign Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes (BECTS). Seizures originate centrotemporally from the Rolandic area of the brain (other names for the Rolandic fissure are the central fissure and most commonly the central sulcus).

"Central Sulcus Diagram" by jimhutchins. "Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0" CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Figure 4.1 showing the central sulcus (Rolandic fissure) which is the area is affected by BRE.

Symptoms

Seizures

Benign Rolandic Epilepsy is characterized by focal motor seizures. These focal motor seizures frequently effect the oropharynx and thus hypersalivation, anarthria, and a facial droop are common clinical symptoms seen during these seizures. Seizures in BRE usually occur at night or shortly after waking and thus an EEG during sleep is preferred. Rarely a Jacksonian march up to generalized tonic-clonic and even status epilepticus will be seen.

Onset of seizures typically occurs between the ages of 3 and 13 years old with the mean onset being at 7 years old. The majority of patients with BRE enter remission by age 13. Most children have less than 10 total seizures before the disorder spontaneously resolves.

EEG

EEG in BRE will show high amplitude biphasic spike and slow wave complexes seen maximally in centrotemporal areas. Epileptiform in BRE is best seen during sleep.

From "The Pediatric EEG", by David Valentine M.D., 2020, (https://www.learningeeg.com/pediatric). Copyright 2020 by David Valentine

Figure 4.2 Showing centrotemporal spike and wave complexes in a patient with BRE.

Treatment & Prognosis

Prognosis

Prognosis for BRE is generally good as seizures spontaneously resolve in the majority of patients. Occasionally there are minor cognitive and behavioral abnormalities associated with higher frequency of seizures in BRE, but typically patients have less than less than 10 total seizures. Rarely, seizures persist into adulthood.

Treatment

Because BRE tends to spontaneously resolve, treatment with AEDs is rarely recommended. Frequent seizures occurring during the day time and the progression of focal motor seizures to GTC's are an indication for the use of AEDs. In these cases, Carbamazepine tends to be the front line medication used.

Key Takeaways

- Benign Rolandic Epilepsy is characterized by focal-motor aware seizures originating from the centrotemporal region of the brain.

- Benign Rolandic Epilepsy has a characteristic centrotemporal spike pattern seen on EEG.

- The majority of children have less than 10 total seizures, before spontaneously resolving.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G3eAyihD2MM

MYOCLONIC-ASTATIC EPILEPSY (DOOSE SYNDROME)

Introduction

Myoclonic-Astatic Epilepsy (MAE), also known as Doose Syndrome is a pediatric seizure disorder commonly affecting children between the ages of 2-5 years that is characterized by frequent myoclonic and atonic seizures. MAE often presents with developmental delay, cognitive impairment, and behavioral challenges.

MAE affects males more often than females at a ratio of 2:1 after the first year of life. During the first year of life literature suggests that MAE will affect the sexes at roughly the same rate.

Symptoms

Epilepsy

MAE's hallmark symptoms are frequent myoclonic and atonic seizures, however it is not uncommon for other seizure types to be witnessed in patients with MAE. Other seizures may include generalized tonic-clonic, absence, tonic, and progression to non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE). Patients can have hundreds of seizures in a single day, and most frequently have seizures in the morning shortly after waking. Sometimes these seizures are isolated, but they often tend to cluster thus increasing their risk to slip into status-epilepticus.

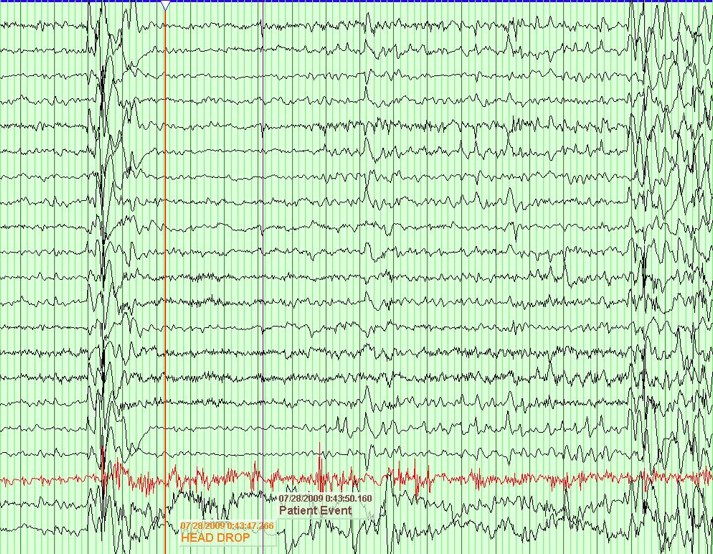

EEG in MAE typically reveals bursts of 2-5 Hz polyspike and wave complexes that are generally superimposed onto otherwise normal looking backgrounds. An important feature in differentiating MAE from other pediatric seizure disorders like LGS is the presence of a relatively normal PDR and sleep architecture.

From "Peds Epilepsy Syndromes", by Shanna Swartwood M.D., 2024

Figure ___ 2.5-5 Hz polyspike and wave seen during an atonic seizure in an MAE patient.

Cognitive Impairment

Cognitive outcomes in MAE are highly variable. Some experience normal cognition while others may have severe intellectual disability. The literature suggests that seizure frequency is correlated to the cognitive outcome as those who attain freedom from seizures tend to have more favorable cognitive outcomes. Changes in behavior are another commonly associated symptom with MAE. Up to 1/5th of documented MAE cases are diagnosed with ADHD.

Treatment & Prognosis

Treatment efficacy of MAE varies as some enter complete remission of seizures, and others have intractable epilepsy. MAE is largely considered a generalized seizure disorder and is treated as such with ethosuximide which is a common AED for controlling generalized seizures. The standard of care is to pair the AED's with dietary therapy which most often consists of the ketogenic diet.

Prognosis in MAE varies depending on the age of onset, frequency of seizures, and seizure control. The literature suggests that roughly 3 in 5 children will have a complete remission from seizures and no longer require treatment. In other children, seizure control may range from well controlled to intractable. In children who do not have seizure freedom, cognitive impairment tends to increase in severity.

Key Takeaways

- Myoclonic-Astatic Epilepsy (MAE) is characterized by frequent myoclonic and atonic seizures.

- Bursts of 2-5 Hz polyspike and wave discharges superimposed onto otherwise normal backgrounds are a common characteristic of MAE.

- Prognosis is often dependent on factors such as seizure frequency, age of onset, and seizure type.

- Dietary therapy is effective in the treatment of MAE.