Introduction: Why Study Taylor Swift

Emily January

“Taylor Swift only writes sappy love songs.”

“My tax dollars shouldn’t be paying for this.”

“Higher education is a joke!”

These and other comments represent the kinds of reactions people have had when learning that I teach a Taylor Swift class at the university where I’m employed. However, the class isn’t a new idea and it isn’t my idea. Classes about the super star are being offered at Harvard, Northeastern, Berkeley, Stanford, and Arizona State. Even the University of Melbourne held a Swiftposium in conjunction with universities across Australia.

We decided to offer the class because one of my colleagues read about her alma mater doing so. She told our department chair, who then asked the faculty who would be willing to teach a class. I volunteered and here we are. My class has been written about on many local news sites and even featured on a local news TV channel. But no good deed goes unpunished. After these press gambits, my department started getting phone calls about how Taylor Swift is a witch and that we are doing the devil’s work, and we saw social media comments decrying how far my university has fallen or that the state of higher education is irredeemable. All of these are old ideas (found in any newspaper over the past 100 years about whatever the latest craze is) and are without merit. The dean of my college (the arts and humanities) wrote an op-ed in a local newspaper explaining why, comparing Swift to revered poet and playwright of another century: William Shakespeare. He faced many similar criticisms during his time, as it is a common hobby for those in any era to be skeptical of what’s new, what’s beloved, what’s innovative, and, especially, in the case of Taylor Swift, of what women happen to love.

So, why offer a Taylor Swift class? Why study her? I’ll outline those reasons here.

First, student engagement has been the best result of this course. I’ve never had a class fill as quickly as when my Taylor Swift class opened for registration. Students were interested and eager to engage in talking about their favorite pop star. While it is offered as an English class, students from across campus registered for it as a humanities credit, including majors in family studies, psychology, mechanical engineering, communication, elementary education, and computer science. Further, we opened a graduate section of the course because our MA in English students were jealous that the undergrads got “all of the cool classes.” Running the class consists of teaching all of the concepts I always teach (the rhetorical situation, identification, research coding, critical analysis, etc.), but through the lens of a person that these students care about. They may not care about Shakespeare or Whitman or Hemingway or Woolf. But they do care about Taylor Swift. I have not had to keep attendance for this class. The students show up, ready to discuss and having read all of their assigned homework.

Second, one student, a mechanical engineering major, told me that he’s never learned English concepts so quickly and neither has he ever cared about them much. He found that viewing the concepts through the lens of his favorite singer helped him to understand more fully than he ever had before. He and my other students have learned how language functions, how analyzing words can open up deeper meanings, and how visual mediums add to the written word. They have learned that rhetoric matters, and that how Swift presents herself through branding impacts the way we see her and therefore engage. All of these are critical skills for the workplace, as we live in an information economy. Knowing how to read, write about, connect, synthesize, and share ideas is key to any career.

Third, Taylor Swift and her many talents speak to the value of the humanities. Swift does what many of our more creative students do. She writes and creates beauty that uplifts and comforts; she entertains through music, lyrics, and dance; she produces films and videos that encapsulate the experiences many of us have had in our personal relationships. She highlights the wonder of the world through her art, and her work reminds us of the value of poetry, music, and literature in our lives. According to Sarah Churchwell (2021), a professor of American Literature at the University of London, “Doing humanities … means recognising that our institutions of education are not the only places where knowledge is produced or acquired. There is a wealth of knowledge across our society about humanistic ideas, and ideas of being human.” There’s knowledge from lived experiences, from everyday people, and yes, from Taylor Swift. This is an idea that Paolo Freire (1996) popularized in the academy with his work on the pedagogy of the oppressed. He knew that everybody brought knowledge to the classroom, and he modeled a type of teaching that most educators use today. It depends on a teacher acting as a guide to students and allowing everybody in the classroom to have a voice. Collectively, we know more than we think we do, and when professors create space for students to share their experiences and knowledge, we all learn.

Swift is a talented writer—she isn’t just a “teeny bopper” pop star (as my grandma would say). Taylor Swift is a poet with literary ambitions and just as much talent. She’s a model of creative production for our students interested in becoming writers or poets or filmmakers. In fact, Swift represents herself in the “All Too Well” short film as a novelist at the end of the video. Her latest album, released on April 19, 2024, is titled The Tortured Poets Department. She styles herself as a literary type, which is why scholars have compared her to Sappho, the ancient Greek poet, and Sylvia Plath, known for her confessional poetry of the 1960s.

The complex nature of Swift’s lyrics shows us just how sophisticated her work is. These lyrics cause us to think about double meanings, and they use metaphor and simile and engage in imagery related to seasons, colors, and flowers. For example, the first two stanzas of her song “Getaway Car” carry multiple allusions to literature and deeper meanings.

“It was the best of times, the worst of crimes

I struck a match and blew your mind

But I didn’t mean it, and you didn’t see it

The ties were black, the lies were white

In shades of gray in candlelight

I wanted to leave him, I needed a reason.”“‘X’ marks the spot where we fell apart

He poisoned the well, I was lyin’ to myself

I knew it from the first Old Fashioned, we were cursed

We never had a shotgun shot in the dark (oh!)”

The first line is an allusion to Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. She takes one of the most famous opening lines of literature “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” and connects her audience to the idea that every era, no matter who the poet or writer is, has its ups and downs. She then connects that to a romantic relationship, one of the most important connections many of us will have in our lives. We can all relate to a relationship (romantic or not) that might be difficult. To us, those granular experiences are what makes our lives most memorable, no matter what’s happening on a grander or more political scale. Further, the personal is political.

The second line plays with the imagery of a lit match, which ignites quickly and blows out quickly. Swift turns this on its head by noting that she “blew your mind,” meaning that the match, which either dies out or starts a fire, did the latter, but through “blowing.” It’s a beautiful and intricate way to use language, especially images that are so familiar to us.

The fourth line uses the imagery of a black-tie event, but “ties” it to another way that the color black is often used in common speech, as an opposite to “white.” And we all know that white lies tend to be harmless, and might actually be the most common way that any of us engage in lying. She further complicates the idea by bringing in the color gray, noting in the next line that the candlelight (again, reminiscent of romance or a black-tie event) is showing her shades of gray. There is nuance in her feelings, and it reflects the nuance in any relational experience. People aren’t all good or all bad. Things aren’t “black and white.” Shades of gray always exist.

The next stanza uses a lot of familiar language to say something new. X marks the spot is a reference to pirates or treasure. Poisoning the well is a logical fallacy, which refers to when you try to discredit somebody before they can represent themselves. The words Old Fashioned do double duty here: an Old Fashioned is an iconic alcoholic drink, a classic. According to Troy Patterson (2011), in his online article about the meanings behind the drink, an Old Fashioned is both “manly” and “something your grandmother drank.” Further, the Old Fashioned is considered the first cocktail, and the drink includes a cherry and an orange peel. Make of that imagery what you will. But because the relationship she’s writing about was “cursed” from the “first,” the idea of the first invented cocktail becomes even more poignant. And if it is doomed from the start, it’s a known problem from the “first.” The rhyming of this phrase also appeals to the audience.

Further, engaging in a relationship in the way that the narrator of this song may want can also be considered old fashioned, and do male-female relationships really work in our modern world from an old-fashioned perspective? She’s referring both to the first date and the drink they had along with the values she may want in a relationship. But she finds that this may be cursed (perhaps an allusion to the story of Eve in the Garden of Eden).

The shotgun shot in the dark combines two common phrases in which shooting is a metaphor for other concerns. First of all, a shotgun wedding refers to one in which the couple marries quickly in order to hide an unintended pregnancy. This sort of response to an unplanned pregnancy can also be considered somewhat “old fashioned.” And a shot in the dark is taking a chance on something that may not have any chance. She has poetically complicated the idea of taking a chance on a relationship by not just taking a shot in the dark, but by doing it hastily, like a shotgun wedding. The alliteration of the phrase is also appealing and fun to say. And her point is that there is no “shot” in this particular situation. Yet, we’ve all been in relationships like that. Doomed from the start. There’s a lot to unpack here, and this is just a snippet of one of her 260 released tracks, as of the release of this book.

All of this said, critics, like the ones I mentioned at the beginning, are focused on the wrong critiques. The question isn’t whether or not Swift and her work are worth studying. The questions are much deeper. Each week in my class we worked to unpack those questions, focusing on critical approaches to girlhood, what it means to be a fan (is it culty?), feminism, queer allyship and identity, politics, business, poetry, race, romantic relationships, and education.

In terms of girlhood, discussed in Chapter 1 of this book, we asked what it means to be an “all-American girl” and explored how carefully Swift cultivated that image for herself as a young artist. Can any girl be all-American? Who is left out of images of girls as perfect, virginal, and obedient? And what do these ideas around girlhood do to the girls who hear them? What do body image and eating disorders have to do with all of this? Further, what is purity and how do child stars, particularly girls, make a transition from childhood to adulthood.

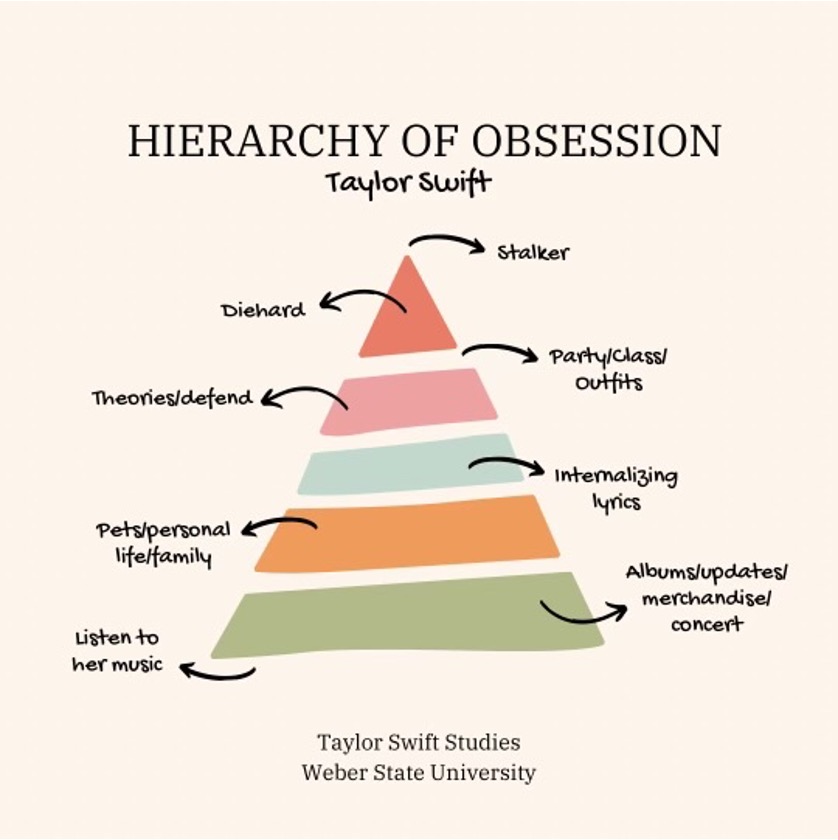

In being a fan, explored in Chapter 2, we examined our level of commitment to this pop culture icon and questioned the authenticity of it. Are we enamored with a real person, or is she a master marketer and/or a brand? We ultimately engaged in visual design to create a hierarchy of Swiftiness in order to unpack what it means to be a fan. This was fun, but it also gave students a way to see levels of devotion and how various audiences might feel differently than they do about Swift. My graduate students were more willing to engage in a critical analysis of their own admiration of Swift as opposed to the undergraduates, who tended to hold onto their love of Swift and resisted critiques of their fan status.

In Chapter 3, this book covers discourses of feminism surrounding Swift and how her feminism is considered to be too focused on white women and normativity, excluding women of color, global women, and queer women. Students also engaged enthusiastically with Swift’s persona as a queer ally, and these discussions are outlined in Chapter 4. We defined what it means to be an ally and how social justice concerns surrounding those we love might be more pressing than a simple music video could address. We asked ourselves about how allyship might be more complicated than lip service and how selling products during pride month might have ethical implications.

We also asked about Swift’s political involvement, represented in Chapter 5. Should public figures without particular qualifications get involved in politics? What effects does this have on fans? On celebrities’ careers? We examined academic articles about power, Machiavellianism, celebrity influence, and who gets to speak up when it comes to politics. Is the personal truly political? We recalled the political fallout of The Chicks in 2003 and wondered whether or not women are more punished than men for speaking up about their political beliefs.

When it comes to Swift as a savvy business woman, we discussed questions of authenticity, capitalism, and marketing, and those are represented in what students wrote for Chapter 6. Are all of the stories and songs we know about Swift’s life true? Are they an image she wants us to believe, and how does that affect the way we consume media, from any celebrity? Public images are carefully crafted to reach particular audiences, and this led us to engage in rhetorical analyses of Swift’s public identity and her fans. We also discussed how carefully crafting a public identity is a project we are all engaged in now, thanks to social media.

Examining Swift’s work as poetry was a favorite approach, and we share some of these ideas in Chapter 7. We engaged in questions and comparisons, looking at how her work is a mode of the confessional. Confessional poets are well known, establishing the genre in the 1950s and 60s. We tried to see if we could locate her work within that tradition, and further found that Swift’s work is not only confessional, but that some of it functions as a form of protest. She has protest songs (“Miss Americana and the Heartbreak Prince”) that reminded me of the great tradition of protest novels, like Native Son by Richard Wright. We asked about the genres of her work and found ourselves discussing the many types of literature that have changed the way social structures in the United States function over the last 100 years.

In Chapter 8, we ask questions about race and Swift’s reinforcement of whiteness through her persona. In class, we discussed whether or not she can or should represent her fans from other ethnicities and cultures. And if not, how can she most ethically represent the many cultural styles of dance, music, and beat that she uses in her music and videos? What are some of the complications of those videos? Not only were we concerned with the ethics surrounding Swift’s use of images and words, but we engaged in looking at artists of color who do similar work as Swift in terms of the confessional, protest, or questions of authenticity. Critiques of Swift led us to learn about different artists in class and the way they are contributing to the big conversations happening in our country.

When it comes to love and relationships, covered in Chapter 9, we examine the age-old question of whether or not public figures should be allowed to have private lives. And, if a public figure writes about their private life in order to release an album, does that make it fair game? We also examined the misogyny of critiquing a woman’s dating habits and labeling her in certain ways, when perhaps male celebrities don’t get the same sort of critiques. In Chapter 10, we look at Taylor Swift as an educator because she has become the subject of many courses in higher education. We trace the success of Swift-themed classes and events to Gen Z’s loneliness, and we attempt to understand how her cultural impact contributes to her fanbase, rather than being only about making a buck. If we harness the popularity of Swift into social events that connect young, lonely, pandemic-affected people, we begin to address a social problem that plagues so many.

With all of the many themes we can untangle based on Taylor Swift, the most important question we can ask in a classroom is this: What can we learn? This is how we approached the class, and it has been successful. Students demonstrated this success through their engagement, enthusiasm, conversations, and written work. Can we turn this into something on their resumes? Perhaps. We have compiled our ideas into this book. The days we spent pooling our ideas and writing together were rewarding and full of chatter, hard work, research. Students took their ideas and professionalized the class experience, engaging in real-world collaboration, information gathering, synthesis, and production.

Individually, students engaged in art projects and fan fiction, among other research ideas. One student spent the semester coding a game of Taylor Swift lyrics. The skill he used to code, learned from his major in Computer Science, has been applied through a project and topic he cared about. It’s fun and the class found it engaging and delightful. Another student used Britney Spears’s lyrics and put them to the tune of Swift’s “You’re Losing Me” to demonstrate the lack of agency Spears had in her early career and to “rewrite” Spears’s music in a more empowered, liberated, and feminist format. Another made mood boards and phone wallpaper based on the aesthetics of different Swift albums. Three students made podcasts and covered the social issues we discussed in class from their individual perspectives. Many students chose to write traditional research papers, and they engaged in complex data coding and infographic design to share their findings.

All of these projects and moments happened through something seemingly inconsequential; yet, when a pop star improves the economy, donates to food banks in every city she plays in, earns over a billion dollars, and influences a generation of women to engage in what they love by speaking to their very real lived experiences, I’d call that pretty consequential. And studying the many facets of Swift’s persona, music, and talent doesn’t hurt anybody. Haters are gonna hate, but my students and I are going to shake it off. We turned our love of Swift into a hands-on learning experience that none of us will ever forget.

References

Churchwell, S. (2021, November 12). The value of the humanities goes way beyond money and jobs. Talking Humanities. https://talkinghumanities.blogs.sas.ac.uk/2021/11/12/the-value-of-the-humanities-goes-way-beyond-money-and-jobs/

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (revised). New York: Continuum, 356, 357-358.

Patterson, T. (2011, November 3). The Old-Fashioned. Slate. https://slate.com/human-interest/2011/11/the-old-fashioned-a-complete-history-and-guide-to-this-classic-cocktail.html

Swift, T. (2017). Getaway Car. reputation.

Media Attributions

- Swiftie Hierarchy © venicedesigns adapted by January, Emily is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license