Middle Adulthood Required Reading for Week 6 – HDFS 1500 Spring 2025

Middle Adulthood

The Climacteric

One biologically based change that occurs during midlife is the climacteric. During midlife, men may experience a reduction in their ability to reproduce. Women, however, lose their ability to reproduce once they reach menopause.

Menopause

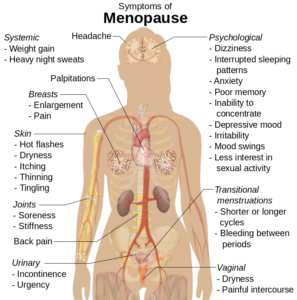

Menopause refers to a period of transition in which a woman’s ovaries stop releasing eggs and the level of estrogen and progesterone production decreases. After menopause, a woman’s menstruation ceases (U. S. National Library of Medicine and National Institute of Health [NLM/NIH], 2007).

Changes typically occur between the mid 40s and mid 50s. The median age range for a women to have her last menstrual period is 50-52, but ages vary. A woman may first begin to notice that her periods are more or less frequent than before. These changes in menstruation may last from 1 to 3 years. After a year without menstruation, a woman is considered menopausal and no longer capable of reproduction. (Keep in mind that some women, however, may experience another period even after going for a year without one.) The loss of estrogen also affects vaginal lubrication which diminishes and becomes more watery. The vaginal wall also becomes thinner, and less elastic.

Menopause is not seen as universally distressing (Lachman, 2004). Changes in hormone levels are associated with hot flashes and sweats in some women, but women vary in the extent to which these are experienced. Depression, irritability, and weight gain are not necessarily due to menopause (Avis, 1999; Rossi, 2004). Depression and mood swings are more common during menopause in women who have prior histories of these conditions rather than those who have not. The incidence of depression and mood swings is not greater among menopausal women than non-menopausal women.

Cultural influences seem to also play a role in the way menopause is experienced. For example, once after listing the symptoms of menopause in a psychology course, a woman from Kenya responded, “We do not have this in my country or if we do, it is not a big deal,” to which some U.S. students replied, “I want to go there!” Indeed, there are cultural variations in the experience of menopausal symptoms. Hot flashes are experienced by 75 percent of women in Western cultures, but by less than 20 percent of women in Japan (Obermeyer in Berk, 2007).

Women in the United States respond differently to menopause depending upon the expectations they have for themselves and their lives. White, career-oriented women, African-American, and Mexican-American women overall tend to think of menopause as a liberating experience. Nevertheless, there has been a popular tendency to erroneously attribute frustrations and irritations expressed by women of menopausal age to menopause and thereby not take her concerns seriously. Fortunately, many practitioners in the United States today are normalizing rather than pathologizing menopause.

Concerns about the effects of hormone replacement have changed the frequency with which estrogen replacement and hormone replacement therapies have been prescribed for menopausal women. Estrogen replacement therapy was once commonly used to treat menopausal symptoms. But more recently, hormone replacement therapy has been associated with breast cancer, stroke, and the development of blood clots (NLM/NIH, 2007). Most women do not have symptoms severe enough to warrant estrogen or hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Women who do require HRT can be treated with lower doses of estrogen and monitored with more frequent breast and pelvic exams. There are also some other ways to reduce symptoms. These include avoiding caffeine and alcohol, eating soy, remaining sexually active, practicing relaxation techniques, and using water-based lubricants during intercourse.

Fifty million women in the USA aged 50-55 are post-menopausal. During and after menopause a majority of women will experience weight gain. Changes in estrogen levels lead to a redistribution of body fat from hips and back to stomachs. This is more dangerous to general health and wellbeing because abdominal fat is largely visceral, meaning it is contained within the abdominal cavity and may not look like typical weight gain. That is, it accumulates in the space between the liver, intestines and other vital organs. This is far more harmful to health than subcutaneous fat which is the kind of fat located under the skin. It is possible to be relatively thin and retain a high level of visceral fat, yet this type of fat is deemed especially harmful by medical research.

Andropause

Do males experience a climacteric? Yes. While they do not lose their ability to reproduce as they age, they do tend to produce lower levels of testosterone and fewer sperm. However, men are capable of reproduction throughout life after puberty. It is natural for sex drive to diminish slightly as men age, but a lack of sex drive may be a result of extremely low levels of testosterone. About 5 million men experience low levels of testosterone that results in symptoms such as a loss of interest in sex, loss of body hair, difficulty achieving or maintaining erection, loss of muscle mass, and breast enlargement. This decrease in libido and lower testosterone (androgen) levels is known as andropause, although this term is somewhat controversial as this experience is not clearly delineated, as menopause is for women. Low testosterone levels may be due to glandular disease such as testicular cancer. Testosterone levels can be tested and if they are low, men can be treated with testosterone replacement therapy. This can increase sex drive, muscle mass, and beard growth. However, long term HRT for men can increase the risk of prostate cancer (The Patient Education Institute, 2005).

The debate around declining testosterone levels in men may hide a fundamental fact. The issue is not about individual males experiencing individual hormonal change at all. We have all seen the adverts on the media promoting substances to boost testosterone: “Is it low-T?” The answer is probably in the affirmative, if somewhat relative. That is, in all likelihood they will have lower testosterone levels than their fathers. However, it is equally likely that the issue does not lie solely in their individual physiological make up, but is rather a generational transformation (Travison et al, 2007). Why this has occurred in such a dramatic fashion is still unknown. There is evidence that low testosterone may have negative health effects on men. In addition, there are studies which show evidence of rapidly decreasing sperm count and grip strength. Exactly why these changes are happening is unknown and will likely involve more than one cause.[1]

The Climacteric and Sexuality

Sexuality is an important part of people’s lives at any age. Midlife adults tend to have sex lives that are very similar to that of younger adulthood. And many women feel freer and less inhibited sexually as they age. However, a woman may notice less vaginal lubrication during arousal and men may experience changes in their erections from time to time. This is particularly true for men after age 65. Men who experience consistent problems are likely to have other medical conditions (such as diabetes or heart disease) that impact sexual functioning (National Institute on Aging, 2005).

Couples continue to enjoy physical intimacy and may engage in more foreplay, oral sex, and other forms of sexual expression rather than focusing as much on sexual intercourse. Risk of pregnancy continues until a woman has been without menstruation for at least 12 months, however, and couples should continue to use contraception. People continue to be at risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections such as genital herpes, chlamydia, and genital warts. Seventeen percent of new cases of AIDS in the United States are in people 50 and older (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html). Of all people living with HIV, 47% are aged 50 or over (https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv-aids/fact-sheets/25/80/hiv-and-older-adults). Practicing safe sex is important at any age- safe sex is not just about avoiding an unwanted pregnancy… it is about protecting yourself from STDs as well. Hopefully, when partners understand how aging affects sexual expression, they will be less likely to misinterpret these changes as a lack of sexual interest or displeasure in the partner and be more able to continue to have satisfying and safe sexual relationships.

Control Beliefs

Central to all of this are personal control beliefs, which have a long history in psychology. Beginning with the work of Julian Rotter (1954), a fundamental distinction is drawn between those who believe that they are the fundamental agent of what happens in their life, and those who believe that they are largely at the mercy of external circumstances. Those who believe that life outcomes are dependent on what they say and do are said to have a strong internal locus of control. Those who believe that they have little control over their life outcomes are said to have an external locus of control.

Empirical research has shown that those with an internal locus of control enjoy better results in psychological tests across the board; behavioral, motivational, and cognitive. It is reported that this belief in control declines with age, but again, there is a great deal of individual variation. This raises another issue: directional causality. Does my belief in my ability to retain my intellectual skills and abilities at this time of life ensure better performance on a cognitive test compared to those who believe in their inexorable decline? Or, does the fact that I enjoy that intellectual competence or facility instill or reinforce that belief in control and controllable outcomes? It is not clear which factor is influencing the other. The exact nature of the connection between control beliefs and cognitive performance remains unclear.[2].

Brain science is developing exponentially and will unquestionably deliver new insights on a whole range of issues related to cognition in midlife. One of them will surely be on the brain’s capacity to renew, or at least replenish itself, at this time of life. The capacity to renew is called neuorgenesis; the capacity to replenish what is there is called neuroplasticity. At this stage it is impossible to ascertain exactly what effect future pharmacological interventions may have on possible cognitive decline at this, and later, stages of life.

Socio-Emotional Selectivity Theory (SST)

It is the inescapable fate of human beings to know that their lives are limited. As people move through life, goals and values tend to shift. What we consider priorities, goals, and aspirations are subject to renegotiation. Attachments to others, current and future, are no different. Time is not the unlimited good as perceived by a child under normal social circumstances; it is very much a valuable commodity, requiring careful consideration in terms of the investment of resources. This has become known in the academic literature as mortality salience.

Mortality salience posits that reminders about death or finitude (at either a conscious or subconscious level), fills us with dread. We seek to deny its reality, but awareness of the increasing nearness of death can have a potent effect on human judgement and behavior. This has become a very important concept in contemporary social science. It is with this understanding that Laura Carstensen developed the theory of socioemotional selectivity theory, or SST. The theory maintains that as time horizons shrink, as they typically do with age, people become increasingly selective, investing greater resources in emotionally meaningful goals and activities. According to the theory, motivational shifts also influence cognitive processing. Aging is associated with a relative preference for positive over negative information. This selective narrowing of social interaction maximizes positive emotional experiences and minimizes emotional risks as individuals become older. They systematically hone their social networks so that available social partners satisfy their emotional needs. The French philosopher Sartre observed that “hell is other people”.An adaptive way of maintaining a positive affect might be to reduce contact with those we know may negatively affect us, and avoid those who might.

SST is a theory which emphasizes a time perspective rather than chronological age. When people perceive their future as open ended, they tend to focus on future-oriented development or knowledge-related goals. When they feel that time is running out, and the opportunity to reap rewards from future-oriented goals’ realization is dwindling, their focus tends to shift towards present-oriented and emotion or pleasure-related goals. Research on this theory often compares age groups (e.g., young adulthood vs. old adulthood), but the shift in goal priorities is a gradual process that begins in early adulthood. Importantly, the theory contends that the cause of these goal shifts is not age itself, i.e., not the passage of time itself, but rather an age-associated shift in time perspective. The theory also focuses on the types of goals that individuals are motivated to achieve. Knowledge-related goals aim at knowledge acquisition, career planning, the development of new social relationships and other endeavors that will pay off in the future. Emotion-related goals are aimed at emotion regulation, the pursuit of emotionally gratifying interactions with social partners, and other pursuits whose benefits which can be realized in the present.

This shift in emphasis, from long term goals to short term emotional satisfaction, may help explain the previously noted “paradox of aging.” That is, that despite noticeable physiological declines, and some notable self-reports of reduced life-satisfaction around this time, post- 50 there seems to be a significant increase in reported subjective well-being. SST does not champion social isolation, which is harmful to human health, but shows that increased selectivity in human relationships, rather than abstinence, leads to more positive affect. Perhaps “midlife crisis and recovery” may be a more apt description of the 40-65 period of the lifespan.

Divorce and Remarriage

Divorce

Divorce refers to the legal dissolution of a marriage. Depending on societal factors, divorce may be more or less of an option for married couples. Despite popular belief, divorce rates in the United States actually declined for many years during the 1980s and 1990s, and only just recently started to climb back up—landing at just below 50% of marriages ending in divorce today (Marriage & Divorce, 2016); however, it should be noted that divorce rates increase for each subsequent marriage, and there is considerable debate about the exact divorce rate. Are there specific factors that can predict divorce? Are certain types of people or certain types of relationships more or less at risk for breaking up? Indeed, there are several factors that appear to be either risk factors or protective factors.

Pursuing education decreases the risk of divorce. So too does waiting until we are older to marry. Likewise, if our parents are still married we are less likely to divorce. Factors that increase our risk of divorce include having a child before marriage and living with multiple partners before marriage, known as serial cohabitation (cohabitation with one’s expected marital partner does not appear to have the same effect). Of course, societal and religious attitudes must also be taken into account. In societies that are more accepting of divorce, divorce rates tend to be higher. Likewise, in religions that are less accepting of divorce, divorce rates tend to be lower. See Lyngstad & Jalovaara (2010) for a more thorough discussion of divorce risk.

If a couple does divorce, there are specific considerations they should take into account to help their children cope. Parents should reassure their children that both parents will continue to love them and that the divorce is in no way the children’s fault. Parents should also encourage open communication with their children and be careful not to bias them against their “ex” or use them as a means of hurting their “ex” (Denham, 2013; Harvey & Fine, 2004; Pescosoido, 2013).

A “Gray Divorce Revolution”?

In 2013 Brown and Lin referred to a “gray divorce revolution”. The figures certainly seem to support their contention. The rate of divorce had doubled for those aged 50-64 in the twenty years between 1990 and 2010. One in 10 persons who divorced in 1990 was over age 50, by 2010 it was over 1 in 4, accounting for some 25% of all divorces in the USA. Various explanations have been offered for this phenomenon. The “baby boomers” had divorced in large numbers in early adulthood, and a large number of remarriages within this group also ended in divorce. Remarriages are about 2.5 times more likely to end in divorce than first marriages. People are living longer and are no longer satisfied with relationships deemed insufficient to meet their emotional needs. The shift to companionate marriage in the later half of the 20th century had followed this segment of the population into midlife, with divorce rates diminishing or stabilizing for other segments of the population.

Socio-emotional selectivity theory would predict that the shift of perspective from time spent to time remaining would predict people valuing experiences and relationships in the present, rather than holding onto memories of the past, or an idealized vision of what might yet come to be. Nevertheless, Cohen (2018) predicts a substantial decline in divorce rates for those who are not part of the “baby boom” generation, and that marriage rates will stabilize once more in subsequent generational cohorts.[3] There has been a marked decline in divorce rates for those under 45 and the link between college education and marriage is now quite pronounced. People are now waiting until later in life to marry for the first time. The average age is now 27 for women and 29 for men, and it is even higher in urban centers like NYC. However, Reeves et al (2016) show that just over half of women with high school diplomas in their 40s are married, with the figures rising to 75% of those women with Bachelors degrees.[4] Increasing economic insecurity may have played a part in ensuring that marriage may increasingly be correlated with educational attainment and socioeconomic status rather than cohorts based solely on age.

U.S. households are now increasingly single person households. The number is reckoned to be in excess of 28% of all households, and may become the most common form in the near future, if trends in Europe are anything to go by. There, the number of one-person households in countries and Denmark and Germany exceeds 40%, with other major European countries like France not far from reaching that proportion. The number of Americans who are unmarried continues to increases. About 45% of all Americans over the age of 18 are unmarried, in 1960 that number was 28% (US Census, 2017). Around 1 in 4 young adults in the USA today will never marry (Pew, 2014). The diversity of households will continue to increase. Currently, the number of one person households in Japan and Germany is double that of households with children under 18.

Remarriage and Repartnering

Middle adulthood seems to be the prime time for remarriage, as the Pew Research Center reported in 2014 that of those aged between 55-64 who had previously been divorced, 67% had remarried. In 1960, it was 55%.[5] Every other age category reported declines in the number of remarriages. Notably, remarriage is more popular with men than women, a gender gap that not only persists, but grows substantially in middle and later adulthood. Cohabitation is the main way couples prepare for remarriage, but even when living together, many important issues are still not discussed. Issues concerning money, ex-spouses, children, visitation, future plans, previous difficulties in marriage, etc. can all pose problems later in the relationship. Few couples engage in premarital counseling or other structured efforts to cover this ground before entering into marriage again.

The divorce rate for second marriages is reckoned to be in excess of 60%, and for third marriages even higher. There is little research in the area of repartnering and remarriage, and the choices and decisions made during the process. A notable exception is that of Brown et al (2019) who offer an overview of the little that there is, and their own conclusions. One important constraint which they note is that men prefer younger women, at least as far as remarriage is concerned. Indeed, the gap in age is often more pronounced in second marriages than in the first, according to Pew (2014).[6] Allied to the fact that women live, on average, five years longer in the USA, then the pool of available partners shrinks for women. Brown et al (2019), also argue that this is further reinforced by the fact that women have a preference for retaining their autonomy and not playing the role of caregiver again. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of their research is the fact that those who repartner tend to do so quickly, and that longer term singles are more likely to remain so.

Reviews are mixed as to how happy remarriages are. Some say that they have found the right partner and have learned from mistakes. But the divorce rates for remarriages are higher than for first marriages. This is especially true in stepfamilies for reasons which we have already discussed. People who have remarried tend to divorce more quickly than those first marriages. This may be due to the fact that they have fewer constraints on staying married (are more financially or psychologically independent).

- Travison et al (2007) Testoserone levels ↵

- Lachman, M. E., Teshale, S., & Agrigoroaei, S. (2014). Midlife as a Pivotal Period in the Life Course: Balancing Growth and Decline at the Crossroads of Youth and Old Age. International journal of behavioral development, 39(1), 20-31. ↵

- Philip Cohen (2018) The Coming Divorce Decline. Retrieved from https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/h2sk6/. ↵

- Richard Reeves et al (2016). Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/social-mobility-memos/2016/08/19/the-most-educated-women-are-the-most-likely-to-be-married/. ↵

- Livingston, Gretchen (2014). Chapter 2: The Demographics of Remarriage. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/11/14/chapter-2-the-demographics-of-remarriage/. ↵

- Pew (2014) Tying the Knot Again? https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/12/04/tying-the-knot-again-chances-are-theres-a-bigger-age-gap-than-the-first-time-around/ ↵