Late Adulthood Required Reading for Week 7 – HDFS 1500 Spring 2025

Defining Late Adulthood

Defining Late Adulthood: Age or Quality of Life?

We are considered in late adulthood from the time we reach our mid-sixties until death. Because we are living longer, late adulthood is getting longer. Whether we start counting at 65, as demographers may suggest, or later, there is a greater proportion of people alive in late adulthood than anytime in world history. A 10-year-old child today has a 50 percent chance of living to age 104. Some demographers have even speculated that the first person ever to live to be 150 is alive today.

About 15.2 percent of the U.S. population or 49.2 million Americans are 65 and older.[1] This number is expected to grow to 98.2 million by the year 2060, at which time people in this age group will comprise nearly one in four U.S. residents. Of this number, 19.7 million will be age 85 or older. Developmental changes vary considerably among this population, so it is further divided into categories of 65 plus, 85 plus, and centenarians for comparison by the census.[2]

Demographers use chronological age categories to classify individuals in late adulthood. Developmentalists, however, divide this population in to categories based on physical and psychosocial well-being, in order to describe one’s functional age. The “young old” are healthy and active. The “old old” experience some health problems and difficulty with daily living activities. The “oldest old” are frail and often in need of care. A 98 year old woman who still lives independently, has no major illnesses, and is able to take a daily walk would be considered as having a functional age of “young old”. Therefore, optimal aging refers to those who enjoy better health and social well-being than average.

Normal aging refers to those who seem to have the same health and social concerns as most of those in the population. However, there is still much being done to understand exactly what normal aging means. Impaired aging refers to those who experience poor health and dependence to a greater extent than would be considered normal. Aging successfully involves making adjustments as needed in order to continue living as independently and actively as possible. This is referred to as selective optimization with compensation. Selective Optimization With Compensation is a strategy for improving health and well being in older adults and a model for successful aging. It is recommended that seniors select and optimize their best abilities and most intact functions while compensating for declines and losses. This means, for example, that a person who can no longer drive, is able to find alternative transportation, or a person who is compensating for having less energy, learns how to reorganize the daily routine to avoid over-exertion. Perhaps nurses and other allied health professionals working with this population will begin to focus more on helping patients remain independent by optimizing their best functions and abilities rather than on simply treating illnesses. Promoting health and independence are essential for successful aging.

Health in Late Adulthood: Primary Aging

Normal Aging

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (BLSA, 2011) began in 1958 and has traced the aging process in 1,400 people from age 20 to 90. Researchers from the BLSA have found that the aging process varies significantly from individual to individual and from one organ system to another. Kidney function may deteriorate earlier in some individuals. Bone strength declines more rapidly in others. Much of this is determined by genetics, lifestyle, and disease. However, some generalizations about the aging process have been found:

- Heart muscles thicken with age

- Arteries become less flexible

- Lung capacity diminishes

- Brain cells lose some functioning but new neurons can also be produced

- Kidneys become less efficient in removing waste from the blood

- The bladder loses its ability to store urine

- Body fat stabilizes and then declines

- Muscle mass is lost without exercise

- Bone mineral is lost. Weight bearing exercise slows this down.

Link to Learning

Watch this video clip from the National Institute of Health as it explains the research involved in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging. You’ll see some of the tests done on individuals, including measurements on energy expenditure, strength, proprioception, and brain imaging and scans. Watch the The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) here.

Primary and Secondary Aging

Healthcare providers need to be aware of which aspects of aging are reversible and which ones are inevitable. By keeping this distinction in mind, caregivers may be more objective and accurate when diagnosing and treating older patients. And a positive attitude can go a long way toward motivating patients to stick with a health regime. Unfortunately, stereotypes can lead to misdiagnosis. For example, it is estimated that about 10 percent of older patients diagnosed with dementia are actually depressed or suffering from some other psychological illness (Berger, 2005). The failure to recognize and treat psychological problems in older patients may be one consequence of such stereotypes.

Primary Aging

Senescence is the biological aging is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics. It is the process by which cells irreversibly stop dividing and enter a state of permanent growth arrest without undergoing cell death. This process is also referred to as primary aging and thus, refers to the inevitable changes associated with aging (Busse, 1969). These changes include changes in the skin and hair, height and weight, hearing loss, and eye disease. However, some of these changes can be reduced by limiting exposure to the sun, eating a nutritious diet, and exercising.

Skin and hair change with age. The skin becomes drier, thinner, and less elastic during the aging process. Scars and imperfections become more noticeable as fewer cells grow underneath the surface of the skin. Exposure to the sun, or photoaging, accelerates these changes. Graying hair is inevitable, and hair loss all over the body becomes more prevalent.

Height and weight vary with age. Older people are more than an inch shorter than they were during early adulthood (Masoro in Berger, 2005). This is thought to be due to a settling of the vertebrae and a lack of muscle strength in the back. Older people weigh less than they did in mid-life. Bones lose density and can become brittle. This is especially prevalent in women. However, weight training can help increase bone density after just a few weeks of training.

Muscle loss occurs in late adulthood and is most noticeable in men as they lose muscle mass. Maintaining strong leg and heart muscles is important for independence. Weight-lifting, walking, swimming, or engaging in other cardiovascular and weight bearing exercises can help strengthen the muscles and prevent atrophy.

Vision

Some typical vision issues that arise along with aging include:

- Lens becomes less transparent and the pupils shrink.

- The optic nerve becomes less efficient.

- Distant objects become less acute.

- Loss of peripheral vision (the size of the visual field decreases by approximately one to three degrees per decade of life.)[3]

- More light is needed to see and it takes longer to adjust to a change from light to darkness and vice versa.

- Driving at night becomes more challenging.

- Reading becomes more of a strain and eye strain occurs more easily.

The majority of people over 65 have some difficulty with vision, but most is easily corrected with prescriptive lenses. Three percent of those 65 to 74 and 8 percent of those 75 and older have hearing or vision limitations that hinder activity. The most common causes of vision loss or impairment are glaucoma, cataracts, age-related macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy (He et al., 2005).

- Glaucoma occurs when pressure in the fluid of the eye increases, either because the fluid cannot drain properly or because too much fluid is produced. Glaucoma can be corrected with drugs or surgery. It must be detected early enough.

- Cataracts are cloudy or opaque areas of the lens of the eye that interfere with passing light, frequently develop. Cataracts can be surgically removed or intraocular lens implants can replace old lenses.

- Macular degeneration is the most common cause of blindness in people over the age of 60. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) affects the macula, a yellowish area of the eye located near the retina at which visual perception is most acute. A diet rich in antioxidant vitamins (C, E, and A) can reduce the risk of this disease.

- Diabetic retinopathy, also known as diabetic eye disease, is a medical condition in which damage occurs to the retina due to diabetes mellitus. It is a leading cause of blindness. There are three major treatments for diabetic retinopathy, which are very effective in reducing vision loss from this disease: laser photocoagulation, medications, surgery.

Hearing

Hearing Loss, is experienced by 25% of people between ages 65 and 74, then by 50% of people above age 75.[4] Among those who are in nursing homes, rates are even higher. Older adults are more likely to seek help with vision impairment than with hearing loss, perhaps due to the stereotype that older people who have difficulty hearing are also less mentally alert.

Conductive hearing loss may occur because of age, genetic predisposition, or environmental effects, including persistent exposure to extreme noise over the course of our lifetime, certain illnesses, or damage due to toxins. Conductive hearing loss involves structural damage to the ear such as failure in the vibration of the eardrum and/or movement of the ossicles (the three bones in our middle ear). Given the mechanical nature by which the sound wave stimulus is transmitted from the eardrum through the ossicles to the oval window of the cochlea, some degree of hearing loss is inevitable. These problems are often dealt with through devices like hearing aids that amplify incoming sound waves to make vibration of the eardrum and movement of the ossicles more likely to occur.

When the hearing problem is associated with a failure to transmit neural signals from the cochlea to the brain, it is called sensorineural hearing loss. This type of loss accelerates with age and can be caused by prolonged exposure to loud noises, which causes damage to the hair cells within the cochlea. Presbycusis is age-related sensorineural hearing loss resulting from degeneration of the cochlea or associated structures of the inner ear or auditory nerves. The hearing loss is most marked at higher frequencies. Presbycusis is the second most common illness next to arthritis in aged people.

One disease that results in sensorineural hearing loss is Ménière’s disease. Although not well understood, Ménière’s disease results in a degeneration of inner ear structures that can lead to hearing loss, tinnitus (constant ringing or buzzing), vertigo (a sense of spinning), and an increase in pressure within the inner ear (Semaan & Megerian, 2011). This kind of loss cannot be treated with hearing aids, but some individuals might be candidates for a cochlear implant as a treatment option. Cochlear implants are electronic devices consisting of a microphone, a speech processor, and an electrode array. The device receives incoming sound information and directly stimulates the auditory nerve to transmit information to the brain.

Being unable to hear causes people to withdraw from conversation and others to ignore them or shout. Unfortunately, shouting is usually high pitched and can be harder to hear than lower tones. The speaker may also begin to use a patronizing form of ‘baby talk’ known as elderspeak (See et al., 1999). This language reflects the stereotypes of older adults as being dependent, demented, and childlike. Hearing loss is more prevalent in men than women. And it is experienced by more white, non-Hispanics than by Black men and women. Smoking, middle ear infections, and exposure to loud noises increase hearing loss.

Health in Late Adulthood: Secondary Aging

Secondary Aging

Secondary aging refers to changes that are caused by illness or disease. These illnesses reduce independence, impact quality of life, affect family members and other caregivers, and bring financial burden. The major difference between primary aging and secondary aging is that primary aging is irreversible and is due to genetic predisposition; secondary aging is potentially reversible and is a result of illness, health habits, and other individual differences.

Attitudes about Aging

Attitudes about Aging

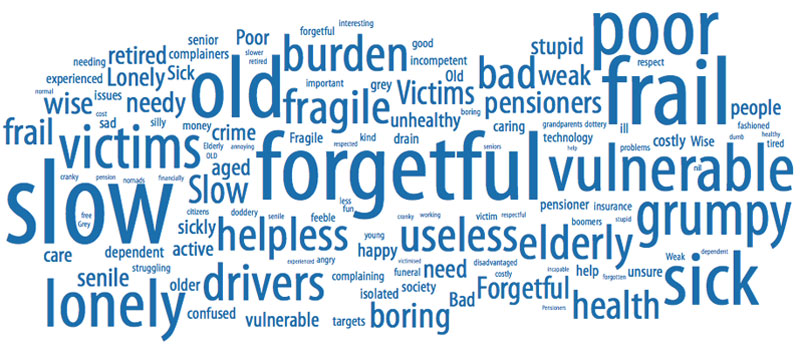

Stereotypes about people of in late adulthood lead many to assume that aging automatically brings poor health and mental decline. These stereotypes are reflected in everyday conversations, the media and even in greeting cards (Overstreet, 2006). The following examples serve to illustrate.

1) Grandpa, fishing pole in one hand, pipe in the other, sits on the ground and completes a story being told to his grandson with “. . . and that, Jimmy, is the tale of my very first colonoscopy.” The message inside the card reads, “Welcome to the gross personal story years.” (Shoebox, A Division of Hallmark Cards.)

2) An older woman in a barber shop cuts the hair of an older, dozing man. “So, what do you say today, Earl?” she asks. The inside message reads, “Welcome to the age where pretty much anyplace is a good place for a nap.” (Shoebox, A Division of Hallmark Cards.)

3) A crotchety old man with wire glasses, a crumpled hat, and a bow tie grimaces and the card reads, “Another year older? You’re at the age where you should start eatin’ right, exercisin’, and takin’ vitamins . . .” The inside reads, “Of course you’re also at the age where you can ignore advice by actin like you can’t hear it.” (Hallmark Cards, Inc.)

Of course, these cards are made because they are popular. Age is not revered in the United States, and so laughing about getting older is one way to get relief. The attitudes above are examples of ageism, prejudice based on age. Ageism is prejudice and discrimination that is directed at older people. This view suggests that older people are less in command of their mental faculties. Older people are viewed more negatively than younger people on a variety of traits, particularly those relating to general competence and attractiveness. Stereotypes such as these can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy in which beliefs about one’s ability results in actions that make it come true.

Ageism is a modern and predominately western cultural phenomenon—in the American colonial period, long life was an indication of virtue, and Asian and Native American societies view older people as wise, storehouses of information about the past, and deserving of respect. Many preindustrial societies observed gerontocracy, a type of social structure wherein the power is held by a society’s oldest members. In some countries today, the elderly still have influence and power and their vast knowledge is respected, but this reverence has decreased in many places due to social factors. A positive, optimistic outlook about aging and the impact one can have on improving health is essential to health and longevity. Removing societal stereotypes about aging and helping older adults reject those notions of aging is another way to promote health in older populations.

In addition to ageism, racism is yet another concern for minority populations as they age. The number of blacks above the age if 65 is projected to grow from around 4 million now to 12 million by 2060. Racism towards blacks and other minorities throughout the lifetime results in many older minorities having fewer resources, more chronic health conditions, and significant health disparities when compared against to older white Americans. Racism towards older adults from diverse backgrounds has resulted in them having limited access to community resources such as grocery stores, housing, health care providers, and transportation.[5]

- US Census Bureau. (2018, April 10). The Nation's Older Population Is Still Growing, Census Bureau Reports. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/cb17-100.html ↵

- US Census Bureau. (2018, August 03). Newsroom. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/cb17-ff08.html ↵

- Heiting, Gary. How vision changes as you age. All About Vision. Retrieved from https://www.allaboutvision.com/over60/vision-changes.htm. ↵

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick Statistics on Hearing. Retrieved from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing. ↵

- African American Older Adults and Race-Related Stress How Aging and Health-Care Providers Can Help. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pi/aging/resources/african-american-stress.pdf. ↵