Death & Dying Required Reading for Week 7 – HDFS 1500 Spring 2025

Why learn about experiences and emotions related to death and dying?

“Everything has to die,” he told her during a telephone conversation.

“I want you to know how much I have enjoyed being with you, having you as my friend, and confidant and what a good father you have been to me. Thank you so much.” she told him.

“You are entirely welcome.” he replied.

He had known for years that smoking will eventually kill him. But he never expected that lung cancer would take his life so quickly or be so painful. A diagnosis in late summer was followed with radiation and chemotherapy during which time there were moments of hope interspersed with discussions about where his wife might want to live after his death and whether or not he would have a blood count adequate to let him precede with his next treatment. Hope and despair exist side by side. After a few months, depression and quiet sadness preoccupied him although he was always willing to relieve others by reporting that he ‘felt a little better’ if they asked. He returned home in January after one of his many hospital stays and soon grew worse. Back in the hospital, he was told of possible treatment options to delay his death. He asked his family members what they wanted him to do and then announced that he wanted to go home. He was ready to die. He returned home. Sitting in his favorite chair and being fed his favorite food gave way to lying in the hospital bed in his room and rejecting all food. Eyes closed and no longer talking, he surprised everyone by joining in and singing “Happy birthday” to his wife, son, and daughter-in-law who all had birthdays close together. A pearl necklace he had purchased 2 months earlier in case he died before his wife’s birthday was retrieved and she told him how proud she would be as she wore it. He kissed her once and then again as she said goodbye. He died a few days later.[1]

A dying process that allows an individual to make choices about treatment, to say goodbyes and to take care of final arrangements is what many people hope for. Such a death might be considered a “good death.” But of course, many deaths do not occur in this way. Not all deaths include such a dialogue with family members or being able to die in familiar surroundings; people may die suddenly and alone, or people may leave home and never return. Children sometimes precede parents in death; wives precede husbands, and the homeless are bereaved by strangers.

In this module, we will look at death and dying, grief and bereavement, palliative care, and hospice to better understand these last stages of life.

The Process of Dying

Aspects of Death

One way to understand death and dying is to look more closely at physiological death, social death, and psychological death. These deaths do not occur simultaneously, nor do they always occur in a set order. Rather, a person’s physiological, social, and psychological deaths can occur at different times.[2]

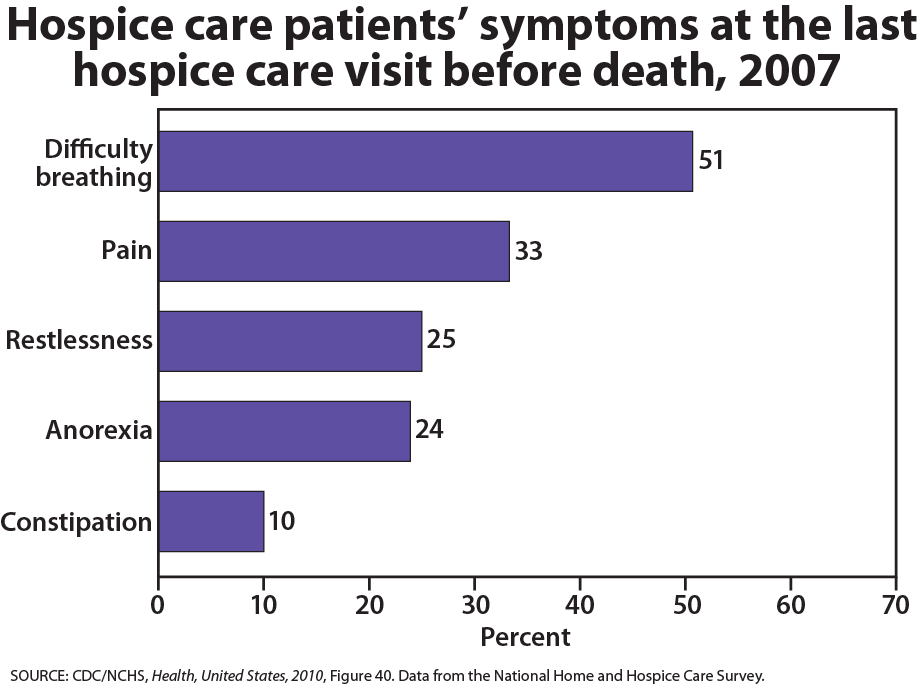

Physiological death occurs when the vital organs no longer function. The digestive and respiratory systems begin to shut down during the gradual process of dying. A dying person no longer wants to eat as digestion slows, the digestive track loses moisture, and chewing, swallowing, and elimination become painful processes. Circulation slows and mottling, or the pooling of blood, may be noticeable on the underside of the body, appearing much like bruising. Breathing becomes more sporadic and shallow and may make a rattling sound as air travels through mucus- filled passageways. Agonal breathing refers to gasping, labored breaths caused by an abnormal pattern of brainstem reflex. The person often sleeps more and more and may talk less, although they may continue to hear. The kinds of symptoms noted prior to death in patients under hospice care (care focused on helping patients die as comfortably as possible) are noted below.

When a person is brain dead, or no longer has brain activity, they are clinically dead. Physiological death may take 72 or fewer hours. This is different than a vegetative state, which occurs when the cerebral cortex no longer registers electrical activity but the brain stems continues to be active. Individuals who are kept alive through life support may be classified this way.

Watch it

This video explains the difference between a vegetative state, a coma, and being brain dead.

Social death begins much earlier than physiological death. Social death occurs when others begin to withdraw from someone who is terminally ill or has been diagnosed with a terminal illness. Those diagnosed with conditions such as AIDS or cancer may find that friends, family members, and even health care professionals begin to say less and visit less frequently. Meaningful discussions may be replaced with comments about the weather or other topics of light conversation. Doctors may spend less time with patients after their prognosis becomes poor. Why do others begin to withdraw? Friends and family members may feel that they do not know what to say or that they can offer no solutions to relieve suffering. They withdraw to protect themselves against feeling inadequate or from having to face the reality of death. Health professionals, trained to heal, may also feel inadequate and uncomfortable facing decline and death. A patient who is dying may be referred to as “circling the drain,” meaning that they are approaching death. People in nursing homes may live as socially dead for years with no one visiting or calling. Social support is important for quality of life and those who experience social death are deprived from the benefits that come from loving interaction with others.

Psychological death occurs when the dying person begins to accept death and to withdraw from others and regress into the self. This can take place long before physiological death (or even social death if others are still supporting and visiting the dying person) and can even bring physiological death closer. People have some control over the timing of their death and can hold on until after important occasions or die quickly after having lost someone important to them. In some cases, individuals can give up their will to live. This is often at least partially attributable to a lost sense of identity. [3] The individual feels consumed by the reality of making final decisions, planning for loved ones—especially children, and coping with the process of his or her own physical death.

Interventions based on the idea of self-empowerment enable patients and families to identify and ultimately achieve their own goals of care, thus producing a sense of empowerment. Self-empowerment for terminally ill individuals has been associated with a perceived ability to manage and control things such as medical actions, changing life roles, and psychological impacts of the illness. [4]

Treatment plans that are able to incorporate a sense of control and autonomy into the dying individual’s daily life have been found to be particularly effective in regards to general attitude as well as depression level. For example, it has been found that when dying individuals are encouraged to recall situations from their lives in which they were active decision makers, explored various options, and took action, they tend to have better mental health than those who focus on themselves as victims. Similarly, there are several theories of coping that suggest active coping (seeking information, working to solve problems) produces more positive outcomes than passive coping (characterized by avoidance and distraction). Although each situation is unique and depends at least partially on the individual’s developmental stage, the general consensus is that it is important for caregivers to foster a supportive environment and partnership with the dying individual, which promotes a sense of independence, control, and self-respect.

Other Models on Grief

One such model was presented by Worden (1991), which explained the process of grief through a set of four different tasks that the individual must complete in order to resolve the grief. These tasks included: (a) accepting that the loss has occurred, (b) working through and experiencing the pain associated with grief, (c) adjusting the the changes that the loss created in the environment, and (d) moving past the loss on an emotional level.[5]

Another model is that of Parkes (1998), which broke down grief into four stages, including: (a) shock, (b) yearning, (c) despair, and (d) recovery. Although comprised of somewhat different stages than those of Kübler-Ross’ model, Parkes’ stages still reflected an ongoing process that the individual goes through, each of which was characterized by different thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Throughout this process, the individual gradually moves closer to accepting the situation, and being able to continue with his or her daily life to the greatest extent possible.[6]

A different approach was proposed by Strobe and Shut (1999), which suggested that individuals cope with grief through an ongoing set of processes related to both loss and restoration. The loss-oriented processes included: (a) grief work, (b) intrusion on grief, (c) denying or avoiding changes toward restoration, and (d) the breaking of bonds or ties. The restoration-oriented processes included: (a) attending to life changes, (b) distracting oneself from grief, (c) doing new things, and (d) establishing new roles, identities, and relationships. Since each individual experiences grief and loss differently, in light of personal, cultural, and environmental factors, these processes often occur simultaneously, and not in a set order.[7]

Link to Learning

Visit “Grief Reactions Over the Life Span” from the American Counseling Association to consider how various age groups deal with the death of a loved one.

We no longer think that there is a “right way” to experience grief and loss. People move through a variety of stages with different frequency and in different ways. The theories that have been developed to help explain and understand this complex process have shifted over time to encompass a wider variety of situations, as well as to present implications for helping and supporting the individual(s) who are going through it. The following strategies have been identified as effective in the support of healthy grieving:[8].

- Talk about the death. This will help the surviving individuals understand what happened and remember the deceased in a positive way. When coping with death, it can be easy to get wrapped up in denial, which can lead to isolation and lack of a solid support system.

- Accept the multitude of feelings. The death of a loved one can, and almost always does, trigger numerous emotions. It is normal for sadness, frustration, and in some cases exhaustion to be experienced.

- Take care of yourself and your family. Remembering to keep one’s own health and the health of their family a priority can help with moving through each day effectively. Making an conscious effort to eat well, exercise regularly, and obtain adequate rest is important.

- Reach out and help others dealing with the loss. It has long been recognized that helping others can enhance one’s own mood and general mental state. Helping others as they cope with the loss can have this effect, as can sharing stories of the deceased.

- Remember and celebrate the lives of your loved ones. This can be a great way to honor the relationship that was once had with the deceased. Possibilities can include donating to a charity that the deceased supported, framing photos of fun experiences with the deceased, planting a tree or garden in memory of the deceased, or anything else that feels right for the particular situation.

Palliative Care and Hospice

Palliative Care

Palliative care is an interdisciplinary approach to specialized medical and nursing care for people with life-limiting illnesses. It focuses on providing relief from the symptoms, pain, physical stress, and mental stress at any stage of illness, with a goal of improving the quality of life for both the person and their family. Doctors who specialize in palliative care have had training tailored to helping patients and their family members cope with the reality of the impending death and make plans for what will happen after.[9]

Palliative care is provided by a team of physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, and other health professionals who work together with the primary care physician and referred specialists or other hospital or hospice staff to provide additional support to the patient. It is appropriate at any age and at any stage in a serious illness and can be provided as the main goal of care or along with curative treatment. Although it is an important part of end-of-life care, it is not limited to that stage. Palliative care can be provided across multiple settings including in hospitals, at home, as part of community palliative care programs, and in skilled nursing facilities. Interdisciplinary palliative care teams work with people and their families to clarify goals of care and provide symptom management, psychosocial, and spiritual support.

Hospice

In many other countries, no distinction is made between palliative care and hospice, but in the United States, the terms have different meanings and usages. They both share similar goals of providing symptom relief and pain management, but hospice care is a type of care involving palliation without curative intent. Usually, it is used for people with no further options for curing their disease or in people who have decided not to pursue further options that are arduous, likely to cause more symptoms, and not likely to succeed.The biggest difference between hospice and palliative care is the type of illness people have, where they are in their illness especially related to prognosis, and their goals/wishes regarding curative treatment. Hospice care under the Medicare Hospice Benefit requires that two physicians certify that a person has less than six months to live if the disease follows its usual course. This does not mean, though, that if a person is still living after six months in hospice he or she will be discharged from the service.

Hospice care involves caring for dying patients by helping them be as free from pain as possible, providing them with assistance to complete wills and other arrangements for their survivors, giving them social support through the psychological stages of loss, and helping family members cope with the dying process, grief, and bereavement. It focuses on five topics: communication, collaboration, compassionate caring, comfort, and cultural (spiritual) care. Most hospice care does not include medical treatment of disease or resuscitation although some programs administer curative care as well. The patient is allowed to go through the dying process without invasive treatments. Family members who have agreed to put their loved one on hospice may become anxious when the patient begins to experience death. They may believe that feeding or breathing tubes will sustain life and want to change their decision. Hospice workers try to inform the family of what to expect and reassure them that much of what they see is a normal part of the dying process.

Watch It

One aspect of palliative and hospice care is helping dying individuals and their families understand what is happening, and what it may imply for their lives. The following video provides an example of palliative care in a hospital setting.

The History of Hospice

Dame Cicely Saunders was a British registered nurse whose chronic health problems had forced her to pursue a career in medical social work. The relationship she developed with a dying Polish refugee helped solidify her ideas that terminally ill patients needed compassionate care to help address their fears and concerns as well as palliative comfort for physical symptoms. After the refugee’s death, Saunders began volunteering at St Luke’s Home for the Dying Poor, where a physician told her that she could best influence the treatment of the terminally ill as a physician. Saunders entered medical school while continuing her volunteer work at St. Joseph’s. When she achieved her degree in 1957, she took a position there.

Saunders emphasized focusing on the patient rather than the disease and introduced the notion of ‘total pain’, which included psychological, spiritual, emotional, intellectual, and interpersonal aspects of pain, the physical aspects, and even financial and bureaucratic aspects. This focus on the broad effects of death on dying individuals and their families has provided the foundation for modern day practices related to hospice care services.[10] Saunders experimented with a wide range of opioids for controlling physical pain but also considered the needs of the patient’s family.

Saunders disseminated her philosophy internationally in a series of tours of the United States that began in 1963. In 1967, Saunders opened St. Christopher’s Hospice. Florence Wald, the Dean of Yale School of Nursing who had heard Saunders speak in America, spent a month working with Saunders there in 1969 before bringing the principles of modern hospice care back to the United States, establishing Hospice, Inc. in 1971. Another early hospice program in the United States, Alive Hospice, was founded in Nashville, Tennessee on November 14, 1975. By 1977 the National Hospice Organization had been formed.

Hospice Care in Practice

The early established hospices were independently operated and dedicated to giving patients as much control over their own death process as possible. Today, it is estimated that over 40 million individuals require palliative care, with over 78% of them being of low-income status or living in low-income countries. [11] It is also estimated, however, that less than 14% of these individuals receive it. This gap is created by restrictive regulatory laws regarding controlled substance medications for pain management, as well as a general lack of adequate training in regards to palliative care within the health professional community. Although hospice care has become more widespread, these new programs are subjected to more rigorous insurance guidelines that dictate the types and amounts of medications used, length of stay, and types of patients who are eligible to receive hospice care. Thus, more patients are being served, but providers have less control over the services they provide, and lengths of stay are more limited. Patients receive palliative care in hospitals and in their homes.

The majority of patients on hospice are cancer patients and they typically do not enter hospice until the last few weeks prior to death. The average length of stay is less than 30 days and many patients are on hospice for less than a week. [12] Medications are rubbed into the skin or given in drop form under the tongue to relieve the discomfort of swallowing pills or receiving injections. A hospice care team includes a chaplain as well as nurses and grief counselors to assist spiritual needs in addition to physical ones. When hospice is administered at home, family members may also be part, and sometimes the biggest part, of the care team. Certainly, being in familiar surroundings is preferable to dying in an unfamiliar place. But about 60 to 70 percent of people die in hospitals and another 16 percent die in institutions such as nursing homes. Most hospice programs serve people over 65; few programs are available for terminally ill children. [13]

Hospice care focuses on alleviating physical pain and providing spiritual guidance. Those suffering from Alzheimer’s also experience intellectual pain and frustration as they lose their ability to remember and recognize others. Depression, anger, and frustration are elements of emotional pain, and family members can have tensions that a social worker or clergy member may be able to help resolve. Many patients are concerned with the financial burden their care will create for family members. And bureaucratic pain is also suffered while trying to submit bills and get information about health care benefits or to complete requirements for other legal matters. All of these concerns can be addressed by hospice care teams.

The Hospice Foundation of America notes that not all racial and ethnic groups feel the same way about hospice care. [14] Certain groups may believe that medical treatment should be pursued on behalf of an ill relative as long as possible and that only God can decide when a person dies. Others may feel very uncomfortable discussing issues of death or being near the deceased family member’s body. The view that hospice care should always be used is not held by everyone and health care providers need to be sensitive to the wishes and beliefs of those they serve. Similarly, the population of individuals using hospice services is not divided evenly by race. Approximately 81% of hospice patients are White, while 8.7% are African American, 8.7% are multiracial, 1.9% are Pacific Islander, and only 0.2% are Native American. [15]

- Overstreet, Laura. Personal Notes. Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. ↵

- Butow, P. (2017). Psychology and end of life. Australian Psychologist, 52(5), 331-334. ↵

- Butow, P. (2017). Psychology and end of life. Australian Psychologist, 52(5), 331-334. ↵

- Butow, P. (2017). Psychology and end of life. Australian Psychologist, 52(5), 331-334. ↵

- Buglass, E. (2010). Grief and bereavement theories. Nursing Standard, 24(41), 44-47. ↵

- Buglass, E. (2010). Grief and bereavement theories. Nursing Standard, 24(41), 44-47. ↵

- Buglass, E. (2010). Grief and bereavement theories. Nursing Standard, 24(41), 44-47. ↵

- American Psychological Association. (2019). Grief: Coping with the loss of your loved one. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/grief. ↵

- National Institute on Aging. (2019). What are palliative care and hospice care? Retrieved from http://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-palliative-care-and-hospice-care ↵

- Richmond, C. (2005). Dame Cicely Saunders. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1179787/. ↵

- World Health Organization. (2019). Palliative care. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/new-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care. ↵

- World Health Organization. (2019). Palliative care: Cancer. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/palliative/en/ ↵

- World Health Organization. (2019). Access to palliative care. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care. ↵

- Hopsice Foundation of America. (2019). Aging America. Retrieved from https://hospicefoundation.org/. ↵

- Campbell, C., Baernholdt, M., Yan, G., Hinton, I. D., & Lewis, E. (2014). Racial/ethnic perspectives on the quality of hospice care. American Journal of Palliative Care, 30(4), 347-353. ↵